ABSTRACT

The scale and extent of violence towards children in different settings is increasingly well documented. However, few studies have attempted to draw on children’s perspectives to understand the linkages between forms of violence, as well as the factors that contribute to, and sustain, violence. We draw together findings from a collaborative project between UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti and Young Lives, a 15-year longitudinal cohort study of children growing up in poverty in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam. This paper highlights findings relating to (1) the importance of understanding the contexts of children’s lives in relation to violence, (2) the ways in which violence is often underpinned by poverty that places pressure on families and communities, (3) the ways in which violence reflects and reinforces social norms and (4) how children’s experiences and their responses to violence are shaped by intersecting inequalities according to age, gender and the wider social and economic context.

Introduction

A wave of landmark studies document the scale of violence affecting children (VAC), including its numerous forms and the settings within which violence occurs (Covell & Becker, Citation2011; Pinheiro, Citation2006; UNICEF, Citation2014). Recent estimates suggest that over a billion children between the ages of 2 and 17 experienced violence in the last year (Hillis, Mercy, Amobi, & Kress, Citation2016). Less explored are the interconnections between structural and institutional factors, such as poverty and discriminatory gender norms and interpersonal violence. Such drivers underpin, reflect and reinforce unequal relations of power between adults and children, as well as between social groups. This paper highlights findings from the contribution of Young Lives, a longitudinal cohort study of children growing up in poverty in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam (Guerrero & Rojas, Citation2016; Morrow & Singh, Citation2016; Ogando Portela & Pells, Citation2015; Pankhurst, Negussie, & Mulugeta, Citation2016; Pells & Morrow, Citation2017; Pells, Ogando Portela, & Espinoza Revollo, Citation2016; Vu, Citation2016) to the UNICEF Office of Research’s Multi-Country Study on the Drivers of Violence Affecting Children (Maternowska & Potts, Citation2017; Maternowska, Potts, & Fry, Citation2016; Maternowska, Potts, Fry, & Casey, Citation2018).

We bridge socioecological and anthropological approaches to the study of childhood and violence to explore intersections of structural and interpersonal violence within the home, school and community and to understand how children experience and respond to such violence.

Researching violence: addressing the context of childhood

The focus of much sociological and anthropological research on children and violence, especially on the Global South, has been on what might be deemed as ‘extreme’ situations, such as conflict and crises (Korbin, Citation2003). What is often missing is research into the everyday, routinised, normalised and often hidden forms of VAC, and how these forms interconnect in a myriad of ways (Parkes, Citation2015; Wells, Burman, Montgomery, & Watson, Citation2014). In a seminal review, anthropologist Jill Korbin (Citation2003) observed the need for greater exploration of the intersections between children’s experiences of multiple forms violence across different settings. Better understanding is needed of the interconnections between the individual, community and structural roots of violence, which combine to affect different children in diverse ways (Parkes, Citation2015).

Within another body of research on children and violence – developmental psychology – the emphasis has been on individual characteristics that correlate with children being at risk of experiencing violence and interpersonal behavioural dynamics, particularly between parents and children, with less consideration of the relationship between violence and structural factors (Ravi & Ahluwalia, Citation2017). Approaches to preventing child abuse and neglect have often rested on normative assumptions regarding childhood with presumed universal application in theory and in practice and insufficient attention to diversity of contexts (Krueger, Vise-Lewis, Thompstone, & Crispin, Citation2015; Wessells, Citation2015). Furthermore, much less is known about the perspectives of children themselves (Leach, Citation2006).

In response to these limitations, we drew on a socioecological approach to ground the research theoretically. The Drivers Study is one of the first attempts to adapt the socioecological framework to understand children’s experiences of violence holistically (Maternowska & Potts, Citation2017). A fuller discussion of the framework’s evolution over the last four decades, and how the Study adapted it to better represent both (1) how violence operating at and within different levels interacts and (2) power and agency in relation to children’s position within the framework, is available in Maternowska and Potts (Citation2017).

We first explored the intersections between ‘drivers’ of interpersonal violence, which we define as being located within the structural and institutional layers of the socioecological model (examples include poverty, economic and social inequality); and second, the divergent ways in which power operates through institutional, community and interpersonal relationships to shape manifestations of violence. Addressing the root causes of VAC requires greater consideration of how power relations, such as those between parents and children, are embedded within, and shaped by, wider structural factors.

Young Lives

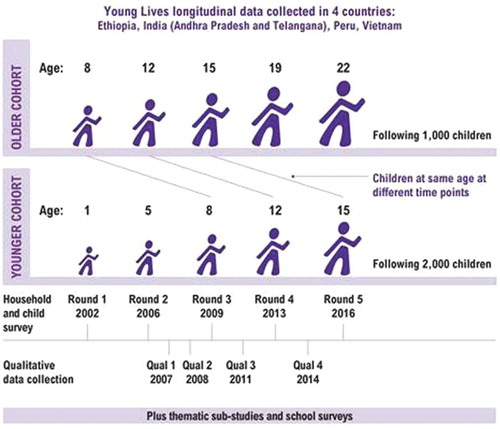

Young Lives is a longitudinal study of children growing up in poverty in Ethiopia, India (in the states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana), Peru and Vietnam. As shown in , the research consists of repeated quantitative and qualitative data collection with two cohorts over a period of 15 years.

The findings below draw on longitudinal qualitative research conducted with 50 children (25 in each cohort; 60 children in Ethiopia, 30 in each cohort) and their caregivers across 4 study sites (5 in Ethiopia) in each country. The sites included urban and rural areas, representing a range of regions and contexts that reflect ethnic, geographic and political diversity. Children’s experiences of violence emerged as widespread and as a matter of concern to children themselves. Violence, in various forms, was mentioned spontaneously on many occasions and by all age groups, during focus group discussions and individual interviews that combined talk-based and creative methods to explore children’s well-being (for a full discussion of methods, including sampling and ethical considerations, see Crivello, Morrow, & Wilson, Citation2013). All children’s names used are pseudonyms.

For this paper, we synthesised findings from Young Lives qualitative research on violence (Guerrero & Rojas, Citation2016; Morrow & Singh, Citation2016; Pankhurst et al., Citation2016; Vu, Citation2016). The original data had been coded using thematic analysis. Using thematic synthesis (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008), we then compiled all the case studies from the original papers into a grid created using descriptive themes emerging from the papers. We generated analytical themes, of which the three most common are included here, along with illustrative examples from the original papers.

Poverty causes stress increasing the likelihood of violence

Young Lives is a poverty study and so unsurprisingly, children’s accounts of violence were set against a backdrop of lack of resources, shaped by factors at the institutional or societal level, such as overcrowded classrooms and lack of social protection measures that mean children’s work is required to ensure family survival, to related factors within the interpersonal or household level, such as lack of family resources to pay for school fees, exercise books and uniforms (Pells & Morrow, Citation2017). Poverty puts great strain on relationships, in families, schools and communities (Bartlett, Citation2018). For example, financial hardship can lead to stress on families, resulting in alcoholism or domestic violence (see the case studies drawn from the lives of Ravi and Nga below). Children may need to work, and this may expose them to violence from employers, or they may struggle with the challenges of balancing working and schooling and are punished when they fail to meet expectations, as the following examples show.

Many children are involved in small-scale subsistence agriculture, and children’s labour is needed especially at peak seasonal times of year. In Ethiopia and India, children often miss school to work but are physically punished when they return to school. Ranadeep, aged 13, explained he was hit when he returned to school after the harvest: ‘They hit us because I didn’t go to school for one month, and … I missed [the lessons]’ (Morrow & Singh, Citation2015, p. 76). Lack of materials for school also means that children are punished: as a boy, aged 7, from India, said: ‘If we don’t get [buy and bring] notebooks, then teachers will beat us’ (Pells & Morrow, Citation2017, p. 19). A mother of a 7-year-old girl in India said the only thing her daughter mentioned about school was that her teacher hit her:

She studies well, … but when there is no uniform and when we delay the fee payments then she will not go, she refuses to go, and she hides behind that wall … and says ‘sir will beat me, they will beat me’. (Morrow & Singh, Citation2014, p. 12)

Poorer students and children from other disadvantaged groups tend to be disproportionately affected by corporal punishment in school and bullying or harassment from other children (Morrow & Singh, Citation2014; Ogando Portela & Pells, Citation2015; Pells et al., Citation2016). Children in Ethiopia described being bullied verbally on account of their impoverished circumstances, including name calling and insults such as ‘child of a destitute’ and fun being made of the poor quality of their clothing or their lack of shoes (Pells et al., Citation2016, p. 31). Across the countries, children reported being absent from school, and even completely ceasing to attend, rather than be stigmatized and bullied (Pells et al. Citation2016).

These examples suggest that violence is inextricably linked with structural and other contextual factors, such as poverty, inequality, ethnicity and gender norms. Our findings echo research on gender-based violence. For instance, Parkes (Citation2015, p. 4) emphasises the need to attend to violence not just as ‘acts of physical, sexual and emotional force, but to the everyday interactions that surround these acts, and to their roots in structural violence of inequitable and unjust socio-economic and political systems and institutions’.

Violence reflects and reinforces discriminatory social and gender norms

VAC occurs at the intersections of unequal generational power relations between adults and children and other markers of social difference, such as class (as seen in the previous section), gender and ethnicity or caste, particularly within institutional contexts, such as the school (Pells & Morrow, Citation2017). Girls’ and boys’ differential experiences and responses to violence are linked with notions of masculinity and femininity, especially in relation to physical punishment. This varies cross-culturally, but in India, for example, norms relating to femininity can mean that girls are required to be docile and submissive, must not be ‘naughty’, while constructions of masculinity may mean that boys accept physical punishment and withstand pain (Morrow & Singh, Citation2014). In Vietnam, powerful patriarchal norms mean that men are entitled to discipline other household members, and this can frame children’s understandings of violence as an appropriate mechanism for educating and controlling younger children and women (Vu, Citation2016). In Peru, girls receive less frequent physical punishment than boys, reinforcing gender stereotypes that see men as strong, able to accept and endure pain and that boys should ‘never show a submissive attitude while being physically punished; rather, they strive to appear resilient and to hide pain’ (Rojas, Citation2011, p. 18).

Violence from teachers was on occasions replicated by children in forms of violent bullying, with the use of violence justified as teaching a lesson, enforcing conformity with harmful gender norms to establish masculine identities for boys. As a head teacher in Peru said ‘Boys have to be treated more roughly, while girls are more delicate and quiet. They cannot be disciplined in the same way’ (Rojas, Citation2011, p. 10). There were differences in seeking help, linked to gender norms in different cultural contexts. For example, whereas boys in Peru were much less likely to seek support when facing difficulties, in India, it was overall girls who were much less likely to seek support.

These accounts suggest that how power operates in institutional contexts can give rise to violence (Horton, Citation2016). Peer bullying can also reflect the normalisation of violence in communities. Bullying and harassment reproduces hierarchies of power and is used to reinforce conformity with social or gender norms, as the following examples illustrate.

Once past puberty, older girls reported experiencing harassment from boys, especially in India (often termed ‘eve-teasing’, see Morrow & Singh, Citation2016) and in Ethiopia. For example, in Ethiopia, at age 12, Haftey described boys harassing her on the way home from school and explained: ‘We cannot study because we always worry about the boys’ threat. We are frightened always’. Later, when age 17, Haftey described her relief at having moved house, closer to her school: ‘In the past, when I was in the village, children were beating us, waiting for us along the road to our school, but here thanks to God there is no one that beats me’ (Pells et al., Citation2016, p. 35). Likewise, in India, Harika, living in rural Andhra Pradesh, described the difficulties that girls faced on the way to school and the fear of harassment from boys. This has led to some girls dropping out of school, and for others, it has caused difficulties in studying (Pells & Morrow, Citation2017).

VAC is therefore intimately intertwined within dynamics of power that are replicated within children’s relationships with each other, often these are demarcated by gender and age. As Horton (Citation2016, p. 211) suggests, understanding violence requires understanding of how power operates and how ‘the ability of individuals to exercise power, and hence to engage in [violence], depends on how they are positioned and position themselves according to wider societal norms regarding race, gender, size, bodily shape, social class and so on….’

Children’s responses to violence are shaped by age and gender norms

How children construct, experience and navigate violence are constrained by norms related to age and gender which change with age across the early life course (Pells & Morrow, Citation2017). This encompasses not just changes in the nature of violence which children may be at risk of, or their actual experience(s) of violence, but also children’s interpretations of what constitutes violence. In other words, what is considered unacceptable at one point in the life course later becomes normalised and vice versa. The following case from India illustrates changing responses to domestic violence over time.

Ravi, a Scheduled Caste boy from rural Andhra Pradesh, had stopped going to school age 9 to work as a bonded labourer to pay off family debt. At age 12, he said: ‘When my Mum and Dad fight I feel very bad. When my Dad hits my Mum we go to try to stop him. Me and my brother go.’ He was adamant that in the future he would not hit his own wife like his father hit his mother. When he was 13 he described having left work as he was hit and insulted by his employer. He was also hit at home by his father. At age 16, Ravi no longer mentioned domestic violence between his parents.

However, he described how he was drawn into fighting his brother-in-law who was hitting his sister, to protect his sister and her young son. Caught up in the violence, he said: ‘She [his sister] told me not get involved and to go inside. He pulled me out and started hitting my sister. I had to free her’. By age 20, Ravi was married and his wife was 4 months pregnant. He wanted to take care of his wife but said: ‘she gets a beating … I hit her when she tells anything … she won’t keep quiet [after the quarrel], she keeps muttering to herself … she just nags, I get angry’ (Morrow & Singh, Citation2016, pp. 24–6).

Ravi’s case shows how structural and interpersonal violence are intertwined and intersect with age and gender norms. Structural violence, including poverty, indebtedness and caste discrimination, shapes exposure to violence and places strain on the household. This is situated in the wider context of intersecting social inequalities of gendered and generational power relations between men and women and between adults and children. This is indicative of how structural and intergenerational forms of violence can combine to generate a cycle of violence towards women, as well as reinforcing and connecting to cycles of violence towards children (Morrow and Singh (Citation2016). Thus, violence affecting women is linked to violence against children, and gender inequalities are a root of both (Namy et al., Citation2017).

In some cases, children who accept violence as normal when they are young start to question it as they become older. Shanmuka Priya, in India, described several forms of violence over the years. At age 8, she said she hit other children to try to protect herself and her younger brother; at age 10, she described being beaten by teachers for being late and for not understanding the lessons, adding that teachers also beat children for ‘being dirty’. She said she was beaten by her parents if she cried or asked for money. She also said male teachers beat children more than female teachers. At age 14, she said she thought primary school teachers hit the children because the teachers did not know it is a crime to ‘mishandle’ children, explaining that the teachers were ‘from the village’ – whereas high school teachers were from further afield and are aware that the government would punish them if they beat the children:

Those who are from the village feel that they can beat us because nobody would care. But those who come from other places are afraid of our background. …I like the teachers who come from far…. We’ve good teachers and they teach well. They don’t beat us. They are jovial with us; they let us play during playtime. …It has changed like that, the environment is nice and cool in this place. (Morrow & Singh, Citation2016, p. 29-30)

Children’s accounts reveal a complex picture of how they respond to violence. Children’s responses included seemingly doing nothing (or crying); seeking help individually; seeking help as a group, which may be a safer way to respond, depending on the problem; avoidance or running away, for example by leaving an abusive employer or refusing to go to school; and intervening, such as when children (especially boys) try to physically stop violence, sometimes using violence themselves against the instigators, or when children adopt more indirect strategies to try and help other children and adults experiencing violence (Pells & Morrow, Citation2017).

These responses are illustrated by findings from research on domestic violence in Vietnam (Pells, Wilson, & Nguyen, Citation2015). Younger children (under 10 years old) described how they often physically distanced themselves from the violence, for example by hiding away or going to another house, whereas older children tended to have developed other strategies, including helping their mothers. Adolescent boys intervened directly to try and protect their mother from abuse, whereas adolescent girls adopted indirect strategies, such as earning money to give to their mothers and so reducing mothers’ dependence on male partners. Children also described the positive role that friendships and school can play in supporting them, if home environments were difficult. However, children who felt different or stigmatised on account of their home situation struggled to learn, and in some cases left school altogether. For example, Nga, aged 17, from Da Nang in Vietnam described the financial pressures on her family and how this led to her father drinking and becoming violent. Nga left school after not passing the entrance exam to secondary school and had been staying up late and going to the bar where her father drinks: ‘I go wake him up and tell him to come home’. In this way, she protected her mother by being the one to let her father back into the house when he was drunk. Nga also worked at her mother’s café and gave her earnings to her mother. Nga explained that she had not had many school friends but instead socialised with ‘a few good children who had to quit school because of their family situation’. This group of friends supported one another ‘because their situation is just as difficult as mine’, including giving money (Pells et al., Citation2015, pp. 60–62).

How children understand violence and their agency in responding to such acts are therefore shaped by wider norms associated with age and gender and can have social and economic implications on children, their families and in their communities.

Conclusion

Young Lives findings showed that violence is pervasive, often routinised and normalised for many children. Children’s descriptions showed the multiple factors that shape their experiences of and responses to violence, and the interconnections between types of violence and the multiple settings in which violence occurs. This changed with age and was shaped by social inequalities related to gender, discrimination and disadvantage experienced by children and intersecting with their position as part of one or more marginalised social groups. Children actively make meaning of their experiences and develop strategies for responding to violence. However, these are constrained by the economic, social and cultural contexts in which children, their families and their communities are living.

The lens provided by a socioecological framework highlights the importance of understanding the context of children’s lives and how structural and institutional factors shape relationships at the community and interpersonal level. Rather than purely focusing on the behaviour of individuals, there is a need to understand and address how interpersonal violence can emerge from structural forms of violence; how structural and institutional factors shape the operation of power in settings, such as the school and the home; and how these dynamics are in turn are navigated by children.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the children and families who participate in Young Lives, and the research teams responsible for data gathering. Special thanks to all Young Lives staff who authored the papers upon which this paper draws – Gabriela Guerrero and Vanessa Rojas in Peru, Alula Pankhurst, Nathan Negussie and Emebet Mulugeta in Ethiopia, Renu Singh in India and Vu Thi Thanh Huong in Vietnam. We also thank Ramya Subrahmanian for permission to cite material from a background paper written for the Know Violence in Childhood report (see Pells & Morrow, Citation2017). This research was funded by UK aid from the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bartlett, S. (2018). Children and the geography of violence: Why space and place matter. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Covell, K., & Becker, J. (2011). Five years on: A global update on violence against children, report for the NGO Advisory Council for follow-up to the UN secretary-general’s study on violence against children. New York, NY: United Nations.

- Crivello, G., Morrow, V., & Wilson, E. (2013). Young lives longitudinal qualitative research: A guide for researchers (Technical Note 26). Oxford, UK: Young Lives.

- Guerrero, G., & Rojas, V. (2016). Understanding children’s experiences of violence in peru: Evidence from young lives (Young Lives/UNICEF Office of Research-Innocenti Working paper WP-2016-17). Florence: UNICEF.

- Hillis, S. D., Mercy, J., Amobi, A., & Kress, H. (2016). Global prevalence of violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics, 137(3), 1–15.

- Horton, P. (2016). Portraying monsters: Framing school bullying through a macro lens. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 37(2), 204–214.

- Korbin, J. E. (2003). Children, childhoods and violence. Annual Review of Anthropology, 32(1), 431–446.

- Krueger, A., Vise-Lewis, E., Thompstone, G., & Crispin, V. (2015). Child protection in development: Evidence-based reflections & questions for practitioners. Child Abuse and Neglect, 50, 15–25.

- Leach, F. (2006). Researching gender violence in schools: Methodological and ethical considerations. World Development, 34(6), 1129–1147.

- Maternowska, M. C., & Potts, A. (2017). The multi-country study on the drivers of violence affecting children: A child-centred and integrated framework for violence prevention. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research. Retrieved from https://www.unicef-irc.org/research/pdf/448-child-centered-brief.pdf

- Maternowska, M. C., Potts, A., & Fry, D. (2016). The multi-country study on the drivers of violence affecting children. A cross-country snapshot of findings. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research. Retrieved from https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/874/

- Maternowska, M. C., Potts, A., Fry, D., & Casey, T. (2018). Research that drives change: Conceptualizing and conducting nationally led violence prevention research. Synthesis report of the “Multi-Country Study on the Drivers of Violence Affecting Children” in Italy, Peru, Viet Nam, and Zimbabwe. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research.

- Morrow, V., & Singh, R. (2014). Corporal punishment in schools in Andhra Pradesh, India: Children’s and parents’ views (Working paper 123). Oxford, UK: Young Lives.

- Morrow, V., & Singh, R. (2015). Children’s and parents’ perceptions of corporal punishment in schools in Andhra Pradesh, India. In J. Parkes (Ed.), Gender violence in poverty contexts: The educational challenge (pp. 67–83). Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Morrow, V., & Singh, R. (2016). Understanding children’s experiences of violence in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, India: Evidence from young lives (Young Lives/UNICEF Office of Research-Innocenti Working paper WP-2016-19). Florence: UNICEF Office of Research.

- Namy, S., Carlson, C., O’Hara, K., Nakuti, J., Bukuluki, P., Lwanyaaga, J., … Michau, L. (2017). Towards a feminist understanding of intersecting violence against women and children in the family. Social Science & Medicine, 184, 40–48.

- Ogando Portela, M. J., & Pells, K. (2015). Corporal punishment in schools: Longitudinal evidence from Ethiopia, India, Peru and Viet Nam (Office of Research- Innocenti Discussion Paper No. 2015-02). Florence: UNICEF.

- Pankhurst, A., Negussie, N., & Mulugeta, E. (2016). Understanding Children’s experiences of violence in Ethiopia: Evidence from Young Lives (Young Lives/UNICEF OoR Working paper WP-2016-25). Florence: UNICEF.

- Parkes, J. (Ed.). (2015). Gender violence in poverty contexts: The educational challenge. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Pells, K., & Morrow, V. (2017). Children’s experiences of violence: Evidence from Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam (Background paper for Ending Violence in Childhood Global Report).New Delhi, India: Know Violence in Childhood.

- Pells, K., Ogando Portela, M. J., & Espinoza Revollo, P. (2016). Experiences of peer bullying among adolescents and associated effects on young adult outcomes: Longitudinal evidence from Ethiopia, India, Peru and Viet Nam (Office of Research-Innocenti Discussion Paper 2016-03). Florence, UNICEF.

- Pells, K., Wilson, E., & Nguyen, T. T. H. (2015). Gender violence in the home and childhoods in Vietnam. In J. Parkes (Ed.), Gender violence in poverty contexts: The educational challenge (pp. 51–63). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Pinheiro, P. S. (2006). World report on violence against children (UN Secretary-General’s Study on Violence Against Children). New York, NY: United Nations.

- Ravi, S., & Ahluwalia, R. (2017). What explains childhood violence? Micro correlates from VACS surveys. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22(S1), 17–30.

- Rojas, V. (2011). ‘I’d rather be hit with a stick… Grades are sacred’: Students’ Perceptions of discipline and authority in a public high school in Peru (Working paper 70). Oxford, UK: Young Lives.

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(45), 1–10.

- UNICEF. (2014). Hidden in plain sight: A statistical analysis of violence against children. New York, NY: Author.

- Vu, T. T. H. (2016). Understanding children’s experiences of violence in Viet Nam: Evidence from young lives (YL/UNICEF OoR Working paper WP-2016-26). Florence: UNICEF.

- Wells, K., Burman, E., Montgomery, H., & Watson, A. (2014). Childhood, youth and violence in global contexts: Research and practice in dialogue. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wessells, M. G. (2015). Bottom-up approaches to strengthening child protection systems: Placing children, families, and communities at the center. Child Abuse and Neglect, 43, 8–21.