ABSTRACT

Violence against young women (VAW) and suicide among young men are serious concerns in Botswana and elsewhere. We examined the overlap in locally perceived causes of these two forms of violence in Botswana using the results from separate studies that used fuzzy cognitive mapping (FCM) to explore perceived causes of the two outcomes. FCM depicts perceived causes of an outcome and their links to the outcome and each other, with weights denoting the perceived strength of each link. The two studies engaged groups of young women, young men, older women, and older men in rural communities. We grouped related concepts into broader categories, then combined category maps for each outcome into a single map including both forms of violence. Based on social network analysis, we calculated the out-degree centrality of each category indicating its influence within the network. Intervention soft-modelling explored the effects of removing individual categories on suicide and VAW. Of 24 causal categories in the combined map, six were shared between both outcomes, 10 were for suicide only, and seven were for VAW only. The six shared categories accounted for 60% of cumulative influence of all categories in the combined map. The three most influential shared categories were financial difficulties, conflict in relationships, and parenting and family issues. Based on local perceptions, avoiding conflict in relationships could reduce suicide by 4.8% and VAW by 18.5%. Eliminating parenting and family issues could reduce suicide by 3% and VAW by 5.4%. Preventing financial difficulties could reduce suicide by 9.3% and VAW by 2.9%. The findings support the idea that some interventions might reduce both personal and interpersonal violence among youth. Analysis of stakeholder perceived causes and soft-modelling of potential interventions could inform community-led co-design of strategies to reduce youth suicide and violence against young women in Botswana.

Background

Suicide among young men and violence against young women are both serious public health problems, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Botswana, now an upper-middle-income country but with high-income inequality, is no exception. In 2019, there were estimated 21.6/100,000 (pcm) deaths by suicide among young men aged 20–24 years in Botswana, and 14.2 pcm among those aged 15–19 years (World Health Organization, Citation2022). Studies in Botswana have reported high rates of experience of physical intimate partner violence in the last one year among adult women: 19% in 2002 (Andersson et al., Citation2007) and 13% in 2011 (Machisa & van Dorp, Citation2012). In 2017, 21% of marginalized young Batswana women (15–29 years) disclosed physical IPV in the last year (Cockcroft et al., Citation2018).

An extensive literature reports factors related to violence against young women and a separate literature examines factors related to suicide and suicide ideation among young men and women. Many studies are from high-income countries, but several recent reviews of the literature about factors related to these two violent outcomes have focused on LMICs or sub-Saharan Africa (Quarshie et al., Citation2020; Shamu et al., Citation2011; Vyas & Watts, Citation2009). Cross-sectional studies of the two forms of violence have described some factors in common, but we have not found published studies that examine factors related to both outcomes together. Interventional studies focus on one or the other outcome separately. There are many reported interventions for prevention of violence against young women in LMICs and sub-Saharan Africa, with combined individual, community and structural approaches reported to be more effective (Keith et al., Citation2023; Yount et al., Citation2017). Interventions for suicide prevention in LMICs often identify youth at risk or those with depression or other mental health issues, offering support to these subgroups (Davaasambuu et al., Citation2019).

In the context of participatory research and stakeholder engagement (Andersson, Citation2011, Citation2018), our question is whether, based on stakeholder perceptions, suicide among young men and violence against young women have shared causes. If they do share perceived causes, community mobilisation interventions to tackle these shared causes could reduce both outcomes. Two recent studies used fuzzy cognitive mapping (Andersson & Silver, Citation2019) to document separately locally perceived causes of suicide among young men (Sarmiento et al., Citation2023a) and violence against young women in rural Botswana (Sarmiento et al., Citation2023b). The maps produced in these two separate exercises suggested considerable overlap between the local community-perceived causes for the two outcomes. This paper describes these shared perceived causes, their influence within the networks of the causes of the violent outcomes, and, based on soft-modelling, the potential impact on both outcomes if these shared causes could be addressed. This analysis is not a predictive exercise but will provide the information input for local stakeholder dialogues about how some interventions might tackle both forms of violence in Botswana.

Methods

Fuzzy cognitive mapping

Fuzzy cognitive mapping (FCM) generates diagrams of perceived causes linked, directly and indirectly, with an outcome (Kosko, Citation1986). Arrows link each cause with its consequence(s), often with weights to indicate the relative strength of influence of each link (Andersson & Silver, Citation2019). The maps are soft models of how stakeholders understand causal relationships that can be used across multiple cultural backgrounds (Sarmiento et al., Citation2020). In two separate exercises, we used FCM to depict local perceptions about the causes of violence against young women and suicide among young men in rural Botswana. Two other papers describe details of the methods and findings of these two studies (Sarmiento et al., Citation2023a); Sarmiento et al., Citation2023b). In each study, four stakeholder groups (young women, young men, older women, older men) from several rural settings created fuzzy cognitive maps of their knowledge of causes of the outcome and weighted the influence of each link from 5 (strongest) to 1 (weakest). A local facilitator supported each session, and a local reporter took notes of the accompanying discussion. Following digitisation of the maps, fuzzy transitive closure analysis (Niesink et al., Citation2013) calculated the influence of each cause on the outcome, taking all other perceived causes into account. An inductive analysis of the causal factors combined them into broader categories. Summary category maps showed the findings across all stakeholders and for individual stakeholder groups.

Combining the maps for the two outcomes

Based on the overall category maps for perceived causes of suicide among young men and violence against young women, we created a combined map that included both outcomes (Dickerson & Kosko, Citation1994; Sarmiento et al., Citation2022). The net influence of each category level relationship in the combined map was the average of the net influence of this relationship in the separate outcome-specific maps. We reviewed the categories from the separate maps for the two outcomes and used a common name for those categories that included the same, or very similar, factors in the map of both outcomes. The combined map had causal categories of three types: those that appeared only on the map for suicide among young men, those that appeared only on the map for violence against young women, and those that appeared on the maps of both outcomes.

Social network analysis

Fuzzy cognitive maps represent networks, with causal categories and outcomes as nodes and the links between them as edges within the network. Social network analysis allows estimation of the role of nodes within a network, including through centrality measures (Knoke & Yang, Citation2019; Papageorgiou & Kontogianni, Citation2012). Outdegree centrality is a measure of the number of outgoing edges from a node in a network. A high outdegree centrality indicates a node that is influential as a cause within the network. We calculated the outdegree centrality of each perceived causal category within the combined map as the sum of the absolute weight of all its outgoing edges (arrows). We normalised this sum by dividing it by the maximum outdegree centrality, thus putting all values in a range between 1 for the most influential category and 0 for a category with no influence. We calculated the sum of all category outdegree centrality values in the combined map and the proportion of this cumulative influence contributed by the shared categories.

Intervention soft-modelling using what-if scenarios

We used a technique described by Kosko et al (Dickerson & Kosko, Citation1994; Kosko, Citation1993) to calculate the potential effect of changing one category in the map on all other categories in the map. The initial activation level of every node (category) in the map is between 0 and 1, where 0 means the node is not present at all and 1 means it is fully operational. For the first iteration, the level of activation of each node in the network is then a function of the sum of the level of activation multiplied by the weight of the link from each other node linked to it, also with a value between 0 and 1 (Özesmi & Özesmi, Citation2004). The modelling repeats the calculations until the further change in activation levels is zero, when the model has reached a stable state. We calculated the effect on the model of keeping the level of activation of certain nodes to zero throughout the iteration; in other words, the scenario if the potential causal category was removed. For each scenario, we calculated the reduction in the activation of nodes compared with the activation in the full model.

Results

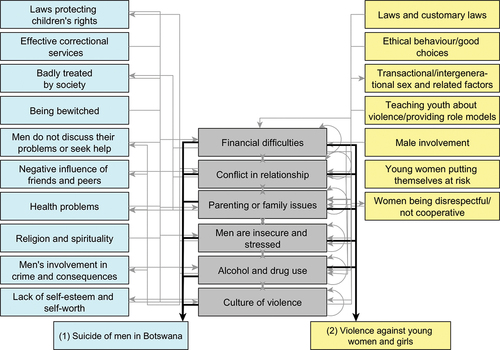

shows the combined category map of suicide among young men and violence against young women. The two outcomes shared six perceived causal categories: financial difficulties, conflict in relationships, parenting and family issues, men being stressed and insecure, alcohol and drug use, and a culture of violence. A further 10 perceived causal categories appeared only on the map of suicide among young men, and seven appeared only on the map of violence against young women. For clarity, only shows the links of shared perceived causal categories. Based on outdegree centrality, three shared categories had the highest influence within the network: financial difficulties (outdegree centrality 1.0), conflict in relationships (0.9) and parenting and family issues (0.7). Overall, the six shared categories accounted for 60% of all the influences in the combined map. Financial difficulties accounted for 18% of all the influence in the combined map, conflict in relationships for 17%, and parenting and family issues for 12%. Appendix 1 shows all relationships in the combined map for the two violence outcomes. Appendix 2 shows the individual factors within each of the perceived causal categories. Appendix 3 shows the final activation levels in the full model for the two outcomes and the various causal categories in the combined map.

Figure 1. Combined fuzzy cognitive map of categories affecting suicide of young men and violence against young women.

shows the decrease from the full model activation value of the two outcomes and other categories on the combined map, removing each of the shared causal categories in turn. The biggest potential change was from removing conflict in relationships, potentially associated with 4.8% decrease in suicide among young men and 18.5% decrease in violence against young women. Removing parenting and family issues was potentially associated with 3.0% decrease in suicide of young men and 5.4% decrease in violence against young women. Removing financial difficulties was associated with the largest potential decrease in suicide among young men (9.3%), as well as 2.9% decrease in violence against young women. It also had important potential effects on intermediate causal categories, with 8.7% reduction in men’s involvement in crime, 4.7% reduction in transactional and intergenerational sex, 10.8% reduction in alcohol and drug use, and 9.6% reduction in men being stressed and insecure.

Table 1. Reduction in the activation level of nodes in the maps with six theoretical scenarios for removing the causal categories appearing on maps of both outcomes

Discussion

Our analysis revealed substantial overlap between perceived causal categories for suicide among young men and violence against young women. This supports the idea that these are not separate problems that need to be investigated and tackled separately. From the standpoint of community perceptions and engagement in prevention, both forms of violence are partly due to shared causes, including parenting and family problems, relationship conflicts, and economic difficulties. Many participatory research authorities note that communities respond best, or only respond, to mobilisation efforts when these are consistent with their own beliefs (Andersson, Citation2018; Israel et al., Citation1998; Macaulay et al., Citation1999). Based as it is on community perceptions of causality, the results from this analysis combining fuzzy cognitive mapping for the two violence outcomes and soft-modelling potential interventions might focus community energies on actions that could lead to reduction in both suicide in young men and violence against young women.

The issues influencing both forms of violence highlighted in our analysis have been reported in previous separate-outcome studies. Financial difficulties were a prominent perceived influence on both outcomes. Suicide is associated with poverty in LMICs (Iemmi et al., Citation2016), male perpetration of partner violence is related to poverty and food insecurity (Awungafac et al., Citation2021; Fulu et al., Citation2013), and women in poverty have higher risks of intimate partner violence (Jewkes, Citation2002). Our soft modelling suggested a potentially important effect of reducing conflict in relationships for both outcomes, especially violence against young women. Other authors have reported that relationship factors (including having multiple partners) are associated with male perpetration of partner violence (Fulu et al., Citation2013), and women’s experience of partner violence (Abramsky et al., Citation2011). A review reported associations between difficulties in intimate partner relationships and suicidal ideation (Kazan et al., Citation2016). The potential role of parenting and family issues surfaced in our analysis aligns with reported associations between childhood abuse, trauma and witnessing violence in the home and experience and perpetration of partner violence (Abramsky et al., Citation2011; Fulu et al., Citation2013; Kimber et al., Citation2018) and reported associations between family relationships and suicidal phenomena in adolescents (Evans et al., Citation2004).

Our intervention soft model suggested only minor impacts on the two outcomes if there was no alcohol or drug use. Other authors have reported important associations of alcohol and drug use with experience and perpetration of partner violence, including in Botswana (Abramsky et al., Citation2011; Barchi et al., Citation2018; Laslett et al., Citation2021), and with suicidal behaviour (Amiri & Behnezhad, Citation2020; Evans et al., Citation2004).

Limitations and strengths

The intervention soft-modelling is not a predictive exercise using empirical effect measures. Based explicitly on locally perceived causes of the two forms of violence, we present the stakeholder perception of potential reductions with different interventions as an input into discussions with those stakeholders about prioritising prevention strategies. There is support for these strategies in the international literature considering the two outcomes separately. Discussing them as possibly influencing both outcomes, based on community perceptions, is likely to generate local community buy-in.

Our analysis is based on a few maps; findings from the intervention soft-modelling might be more stable with more maps. Different individuals mapped the two outcomes, although they were the same types of people (young women, young men, older women, and older men) in the same types of communities (rural communities close to the capital). If the same people created the two maps, their experience creating the first map might have influenced the second.

The research team grouped perceived causal factors into broader categories and our prior beliefs and biases may have influenced categorisation. We mitigated this possibility by involving the fieldworkers who facilitated the mapping sessions in the categorisation and consulting the field notes from the sessions. We assessed potential reductions in outcomes after removing whole categories of causes. Each category includes many factors and in practice it would clearly not be possible to remove a category totally.

The findings reflect the situation in rural communities in southern Botswana and may not be generalizable to community interventions outside this context. But a strength of the study is that it is based on local knowledge and therefore locally relevant and with a good potential for guiding local prevention discussions. While the findings may be specific to a particular context, the procedural and analytic approach could have much wider applicability.

Conclusions

This analysis supports the idea that at least some of the causes of youth suicide and violence against young women are shared in the context of rural Botswana. This could inform discussions and community mobilisation for joint interventions to address both forms of violence.

Ethics review

This study is part of a Grand Challenges Canada project (Grant number R-ST-POC-1909–28463), which received ethical approval from the Botswana Ministry of Health under the Health Research and Development Division IRB (Reference HPDME 13/18/1).

Acknowledgments

We thank the men and women who contributed their time and knowledge in the FCM sessions. The members of Participatory Research at McGill (PRAM) kindly participated in earlier discussions of our results and intervention soft-modelling.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available with the publication.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anne Cockcroft

Anne Cockcroft is a professor of family medicine in CIET-Participatory Research at McGill (PRAM) with a background in respiratory and occupational medicine. Over the last 25 years, she has undertaken large scale community-based participatory research projects in some 20 countries. She works with vulnerable populations to document their access to and experience of health and other services, and with service providers and policy makers to use evidence to develop equitable and effective services. In the last decade, her work has focussed on co-designing interventions, implementing them, and measuring the impact. Her current work includes participatory research to improve adolescent sexual and reproductive health and community responses to the impacts of COVID-19 pandemic in Bauchi State, Nigeria, and a study of community-based interventions to reduce youth personal and interpersonal violence in Botswana.

Ivan Sarmiento

Iván Sarmiento is an independent researcher at CIET, a member of the Groups of Studies in Traditional Health Systems, and the program administrator of Participatory Research @ McGill (PRAM). He has over two decades of experience collaborating with local and Indigenous groups in Colombia. His main interest is in promoting intercultural dialogue between Indigenous traditional medicine and Western medicine, particularly for primary health care. He has contributed to developing procedures for participatory modelling of health issues using fuzzy cognitive mapping, applying these methods in over 20 projects across eight countries.

Neil Andersson

Neil Andersson is a Professor of Family Medicine, director of the amalgamated CIET and Participatory Research at McGill (PRAM) and co-director of the McGill Institute of Human Development and Well-being. His main focus is on method development for large scale participatory approaches that address different health issues. He is particularly concerned about reproducible and culturally safe techniques to build stakeholder voices into systematic reviews, research conceptualization and co-design, intervention development, implementation and analysis. Dr. Andersson’s current interest is in community-led randomized trials of older adult participation in dementia prevention.

References

- Abramsky, T., Watts, C. H., Garcia-Moreno, C., Devries, K., Kiss, L., Ellsberg, M., Jansen, H. A., & Heise, L. (2011). What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 109. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-109

- Amiri, S., & Behnezhad, S. (2020). Alcohol use and risk of suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 38(2), 200–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550887.2020.1736757

- Andersson, N. (2011). Building the community voice into planning: 25 years of methods development in social audit. BMC Health Services Research, 11(supp2), S1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-11-S2-S1

- Andersson, N. (2018). Participatory research—A modernizing science for primary health care. Journal of General and Family Medicine, 19(5), 154–159. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgf2.187

- Andersson, N., Ho-Foster, A., Mitchell, S., Scheepers, E., & Goldstein, S. (2007). Risk factors for domestic physical violence: National cross-sectional household surveys in eight southern African countries. BMC Women’s Health, 7, 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-7-11

- Andersson, N., & Silver, H. (2019). Fuzzy cognitive mapping: An old tool with new uses in nursing research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 75(12), 3823–3830. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14192

- Awungafac, G., Mugamba, S., Nalugoda, F., Sjöland, C. F., Kigozi, G., Rautiainen, S., Malyabe, R. B., Ziegel, L., Nakigozi, G., Nalwoga, G. K., Kyasanku, E., Nkale, J., Watya, S., Ekström, A. M., & Kågesten, A. (2021). Household food insecurity and its association with self-reported male perpetration of intimate partner violence: A survey of two districts in central and western Uganda. British Medical Journal Open, 11(3), e045427. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045427

- Barchi, F., Winter, S., Dougherty, D., & Ramaphane, P. (2018). Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in Northwestern Botswana: The Maun Women’s Study. Violence Against Women, 24(16), 1909–1927. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801218755976

- Cockcroft, A., Marokoane, N., Kgakole, L., Tswetla, N., & Andersson, N. (2018). Access of choice-disabled young women in Botswana to government structural support programmes: A cross-sectional study. Aids Care-Psychological & Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/hiv, 30(sup2), 24–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2018.1468009

- Davaasambuu, S., Phillip, H., Ravindran, A., & Szatmari, P. (2019). A scoping review of evidence-based interventions for adolescents with depression and suicide related behaviors in low and middle income countries. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(6), 954–972. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00420-w

- Dickerson, J. A., & Kosko, B. (1994). Virtual worlds as fuzzy cognitive maps. Presence Teleoperators & Virtual Environments, 3(2), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1162/pres.1994.3.2.173

- Evans, E., Hawton, K., & Rodham, K. (2004). Factors associated with suicidal phenomena in adolescents: A systematic review of population-based studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 24(8), 957–979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2004.04.005

- Fulu, E., Jewkes, R., Roselli, T., & Garcia-Moreno, C. (2013). UN multi-country cross-sectional study on men and violence research team prevalence of and factors associated with male perpetration of intimate partner violence: Findings from the UN multi-country cross-sectional study on men and violence in Asia and the pacific. The Lancet Global Health, 1(4), e187–e207. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70074-3

- Iemmi, V., Bantjes, J., Coast, E., Channer, K., Leone, T., McDaid, D., Palfreyman, A., Stephens, B., & Lund, C. (2016). Suicide and poverty in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry, 3(8), 774–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30066-9

- Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Parker, E. A., & Becker, A. B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19(1), 173–202. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173

- Jewkes, R. (2002). Intimate partner violence: Causes and prevention. The Lancet, 359(9315), 1423–1429. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08357-5

- Kazan, D., Calear, A. L., & Batterham, P. J. (2016). The impact of intimate partner relationships on suicidal thoughts and behaviours: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 585–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.003

- Keith, T., Hyslop, F., & Richmond, R. (2023). A systematic review of interventions to reduce gender-based violence among women and girls in sub-Saharan Africa. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(3), 1443–1464. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211068136

- Kimber, M., Adham, S., Gill, S., McTavish, J., & MacMillan, H. L. (2018). The association between child exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV) and perpetration of IPV in adulthood-A systematic review. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 273–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.11.007

- Knoke, D., & Yang, S. (2019). Social network analysis (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/social-network-analysis/book258181

- Kosko, B. (1986). Fuzzy cognitive maps. International Journal of Man-Machine Studies, 24(1), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7373(86)80040-2

- Kosko, B. (1993). Adaptive inference in fuzzy knowledge networks. In D. Dubois, H. Prade, & R. R. Yager (Eds.), Readings in fuzzy sets for intelligent systems (pp. 888–891). Morgan Kaufmann. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4832-1450-4.50093-6

- Laslett, A. M., Graham, K., Wilson, I. M., Kuntsche, S., Fulu, E., Jewkes, R., & Taft, A. (2021). Does drinking modify the relationship between men’s gender-inequitable attitudes and their perpetration of intimate partner violence? A meta-analysis of surveys of men from seven countries in the Asia Pacific region. Addiction, 116(12), 3320–3332. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15485

- Macaulay, A. C., Commanda, L. E., Freeman, W. L., Gibson, N., McCabe, M. L., Robbins, C. M., & Twohig, P. L. (1999). Participatory research maximises community and lay involvement. BMJ, 319(7212), 774–778. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.319.7212.774

- Machisa, M., & van Dorp, R. (2012). The gender based violence indicators study: Botswana.http://www.bw.undp.org/content/dam/botswana/docs/GovandHR/GBVIndicatorsBotswanreport.pdf

- Niesink, P., Poulin, K., & Šajna, M. (2013). Computing transitive closure of bipolar weighted digraphs. Discrete Applied Mathematics, 161(1–2), 217–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dam.2012.06.013

- Özesmi, U., & Özesmi, S. L. (2004). Ecological models based on people’s knowledge: A multi-step fuzzy cognitive mapping approach. Ecological Modelling, 176(1–2), 43–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2003.10.027

- Papageorgiou, P., & Kontogianni, A. (2012). Using fuzzy cognitive mapping in environmental decision making and management: a methodological primer and an application. International Perspectives on Global Environmental Change, https://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/27194.pdf

- Quarshie, E. N., Waterman, M. G., & House, A. O. (2020). Self-harm with suicidal and non-suicidal intent in young people in sub-saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 234. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02587-z

- Sarmiento, I., Cockcroft, A., Dion, A., Paredes-Solís, S., De Jesús-García, A., Melendez, D., Marie Chomat, A., Zuluaga, G., Meneses-Rentería, A., & Andersson, N. (2022). Combining conceptual frameworks on maternal health in indigenous communities—fuzzy cognitive mapping using participant and operator-independent weighting. Field Methods, 34(3), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X211070463

- Sarmiento, I., Kgakole, L., Molatlhwa, P., Girish, I., Andersson, I., & Cockcroft, A. (2023a). Community perceptions of causes of violence against young women in Botswana: Fuzzy cognitive mapping. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies1–57. in press. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2023.2262413

- Sarmiento, I., Kgakole, L., Molatlhwa, P., Girish, I., Andersson, N., & Cockcroft, A. (2023b). Community perceptions about causes of suicide among young men in Botswana: An analysis based on fuzzy cognitive maps. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. in press. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2023.2262941

- Sarmiento, I., Paredes-Solís, S., Loutfi, D., Dion, A., Cockcroft, A., & Andersson, N. (2020). Fuzzy cognitive mapping and soft models of indigenous knowledge on maternal health in Guerrero, Mexico. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 20(1), 125. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-00998-w

- Shamu, S., Abrahams, N., Temmerman, M., Musekiwa, A., Zarowsky, C., & Vitzthum, V. (2011). A systematic review of African studies on intimate partner violence against pregnant women: Prevalence and risk factors. PloS One, 6(3), e17591. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017591

- Vyas, S., & Watts, C. (2009). How does economic empowerment affect women’s risk of intimate partner violence in low and middle income countries? A systematic review of published evidence. Journal of International Development, 21(5), 577–602. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1500

- World Health Organization. (2022). The Global Health Observatory. Global Health Estimates: Leading Causes of Death. Cause-Specific Mortality, 2000–2019. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death

- Yount, K. M., Krause, K. H., & Miedema, S. S. (2017). Preventing gender-based violence victimization in adolescent girls in lower-income countries: Systematic review of reviews. Social Science & Medicine, 192, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.08.038

Appendix 1.

Adjacency matrix of the category map of causes of suicide among young men and violence against young women

Rows and arrows correspond to the nodes on the map. Each cell indicates the possible relationship between two nodes, from the row to the column. The value in the cell is the weight of the causal relationship. A weight of 0 indicates that participants did not report the relationship. Weights closer to one indicate stronger causal relationships. Negative and positive signs correspond to negative and positive relationships between cause and effect, respectively. Each category has a corresponding code with S for the categories that were present in the map of causes of suicide among men and V for the categories from the maps of violence against women, with a consecutive number according to the order of categories in the maps.

Appendix 2.

Individual factors within each of the combined causal categories

Appendix 3.

Final activation levels in the full model for the two outcomes and the various causal categories in the combined map

The table shows an iterative sequence of calculations for the activation level of each category, starting with the initial status (t0), assuming all the categories are fully activated (value of 1). The system reached a stable state after iteration t5 when the activation levels no longer changed. Categories with activation levels closer to 1 are considered fully activated. This means they would occur if the relationships described in the map occur. Activation levels closer to 0 indicate categories that might not occur even if all the influences described in the map occur.