Abstract

Gruesome graphic evidence such as autopsy photographs and damaged corpses in criminal cases may affect some individuals involved in the trial. Specifically, individuals may suffer from psychological health issues, such as secondary traumatic stress and PTSD, and they may also be susceptible to punitive verdict bias owing to graphic evidence that often elicits a negative emotional response. In this study, we adopt medical-legal illustrations as an alternative for graphic images. The illustrations differed in the amount of detail portrayed (Realistic and inclusive of main Characteristics) and colouring (black and white or colour). Mock jurors (n = 37) were surveyed to determine which is the most suitable approach to describe graphic scenes in three cases. Emotions were assessed. In all three cases, mock jurors chose Characteristics illustrations as the most suitable – a level of detail that exaggerated some details and simplified others. Specialist forensic doctors agreed with this conclusion. Schematics and Realistic (including background information) illustrations were chosen as the most unsuitable. Realistic (including background information) illustrations in particular generated a higher emotional score than the other types.

Introduction

Commencing with leading nations such as United States, Canada and China have also adopted the Jury system. Nowadays, various mental issues are common among those participating as jurors and judges in jury trials. The issues that affect jurors may cause lasting negative physical and psychological effects, and can be affected by factors such as the length of trials (Bornstein, Miller, Nemeth, Page, & Musil, Citation2005; National Center for State Courts, Citation1998) and the responsibility of the judge (Antonio, Citation2008; Kaplan & Winget, Citation1992). For the most part, it is the gruesome graphic evidence that most affects the jurors and is a considerable factor in secondary traumatic stress and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Dabbs, Citation1992; Miller & Bornstein, Citation2004; Miller, Citation2008). Explicit evidence includes photographs of the victim’s wounds, autopsy photographs, crime scenes and the murder weapon. The effect of graphic evidence on jurors has been reported for over forty years (Grady, Reiser, Garcia, Koeu, & Scurich, Citation2018; Kaplan, Citation1985); it has been noted that this is not only a mental health issue but also a public health concern (Lonergan, Leclerc, Descamps, Pigeon, & Brunet, Citation2016). For example, if someone suffers from secondary trauma or PTSD owing to their participation in a criminal trial, it would take time and money to recover from this ordeal (Dunn, Citation2018). Most countries that employ a jury system do not have a strong enough post-trial support system for the jurors (Bertrand & Paetsch, Citation2008; Lonergan et al., Citation2016). As such, if a juror wants medical support, they would have to arrange this for themselves (Cheung, Citation2016; Nanbu, Citation2015).

Legal professionals, such as judges and court staffers, are also negatively affected by criminal trial evidence (Chamberlain & Miller, Citation2008, Citation2009; Flores, Miller, Chamberlain, Richardson, & Bornstein, Citation2008). If judges become non-functional due to secondary trauma and PTSD, it may be possible to cause a breakdown of the criminal justice system (Chamberlain & Miller, Citation2009).

Previous studies caution that graphic evidence could elicit negative emotions, and that this may lead to punitive judgements (Bright & Goodman-Delahunty, Citation2006; Grady et al., Citation2018); this phenomenon is thus in danger of engendering unfair verdicts. In an effort to reduce emotional responses, the effect of colour photographs on jurors versus black and white photos was studied (Oliver & Griffitt, Citation1976; Whalen & Blanchard, Citation1982). Black and white photographs were shown to reduce the emotional reaction, possibly because black and white evidence showed less detail than colour photographs (Salerno & Bottoms, Citation2009). The depth of wounds, in particular, was not visible in black and white photos, and this may affect the assessment of the case.

Medical-legal illustrations play an important role in the legal system. Previous research indicates that medical-legal illustration could shorten the length of a trial and prevent an unfair verdict (Mader et al., Citation2005). There are, however, some problems that have not yet been addressed. First, little research has been conducted on the process of making medical-legal illustrations, and the latest study only considered a lawyer’s point of view and it did not include any murder cases (Mader et al., Citation2005). Second, there has been no standardised approach developed. In medical illustration research, the detail and expression of the artist influences the comprehensibility of the illustration (Houts, Doak, Doak, & Loscalzo, Citation2006; Scheltema, Reay, & Piper, Citation2018; Strong & Erolin, Citation2013). While an illustration created in extremely low detail might be beneficial for the juror, as it could reduce the possibility of secondary traumatic stress and PTSD, it could also elicit a wrongful verdict due to the illustration not transmitting the severity of the crime. Therefore, the most important factor in this research is how to make a medical-legal illustration, and how to determine which representational format is the most suitable to accurately portray the crimes.

Considering the above criminal trial problems and medical-legal illustrations’ technical concerns, this study aims to establish guidelines for efficient medical-legal illustrations in order to reduce jurors’ secondary traumatic stress and PTSD symptoms during criminal trials. In order to accomplish this, we wish to record jurors’ reactions to illustrations that differ in detail and colour and confirm which method of delivery is most suitable to convey accurate information without causing unnecessary mental stress.

Methods

Criminal autopsy photographs

To research the effects of medical-legal illustrations in criminal murder cases, we chose suitable criminal autopsy photographs. We worked with the Department of Forensic Medicine of the Graduate School of Medicine at The University of Tokyo, who shared criminal autopsy photographs and also assessed the accuracy of the illustrations’ details.

This research was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the University of Tokyo (No. 11962- (2)) and Ritsumeikan University (No. Kinugasa-human-2019-8). Additionally, using autopsy photographs for this research had been approved by the appropriate ethics review board at the Department of Forensic Medicine of the Graduate School of Medicine at The University of Tokyo. An opt-out informed consent form was obtained from the family.

First, we noted the different wounds and ages. To confirm juror reactions, a wide variety of cases was needed; therefore, we chose three post-mortem cases with the following case details:

Case 1. 60s; male; cause of death: external carotid artery injury due to penetrating neck trauma; kind of trauma: penetrating.

Case 2. 30s; male; cause of death: thoracic-abdominal trauma and tension pneumothorax (work-related death); kind of trauma: blunt.

Case 3. 5; male; cause of death: multiple trauma (due to falling); kind of trauma: blunt.

Determining representational format

It was essential to determine the type of representational format that would be the most effective way to deliver the most accurate information while reducing mental stress.

The illustrator’s skill aside, three categories of details were determined as essential: high detail – Realistic (realistic depiction); medium detail – Characteristics (exaggerating some parts of the description while preserving simple and flat aspects of other parts); and low detail – Schematics (simplified and schematic depiction) (Pauwels, Citation2005; Strong & Erolin, Citation2013).

Further, another important representational format is the use of colour. Previous research revealed that black and white graphic photographs induced a smaller emotional response than a coloured photograph (Oliver & Griffitt, Citation1976; Salerno & Bottoms, Citation2009; Whalen & Blanchard, Citation1982). Therefore, this research focussed on confirming whether previous research applies for medical-legal illustrations. As such, Case 1 utilised black and white illustrations only. Colour techniques are rarely referred to in medical illustration research.

In terms of colouring technique, we chose to employ two categories of colour: Daub, which does not express gradation and simplifies the colour information for solid colours, and Shadow colouring to express colour layers and gradation (much like picture quality). It is sometimes difficult to determine colour techniques because these depend on each creator and individual characteristics. This study assumed that the representational format may affect the amount of information delivered and have different uses (i.e. low detail is useful to reduce graphic content, and high detail may affect the judgement and cause a harsh verdict). Therefore, this research used one colour technique, Daub Colouring, for Case 2. Additionally, along with detail categories, Shadow colouring was utilised in Case 3 (for instance, in the Realistic illustration, strong expression of coloured layers and gradation, and in the Schematics illustrations, weak expression of shadowing and coloured layers).

We then created each medical-legal illustration through a peer review process performed by two illustrators, one of whom made the prototypes and the other conducted a peer review for expressing correct information and objectivity. This was done as follows:

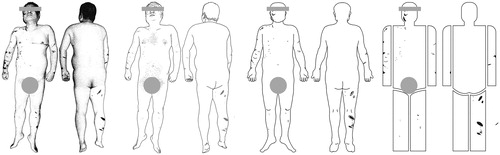

Case 1: Four patterns of illustration in the previously mentioned three categories were developed: Realistic (include shadow, or not - outline only), Characteristics (exaggerating some parts of the description) and Schematics (very low level of detail). All illustrations were expressed in black and white ().

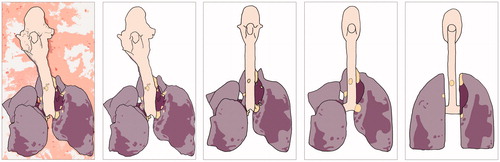

Case 2: Five patterns of illustration were developed: Realistic (to include background information or not), Characteristics and Schematics (medium-low level of detail or very low level of detail). All illustrations utilised Daub colouring ().

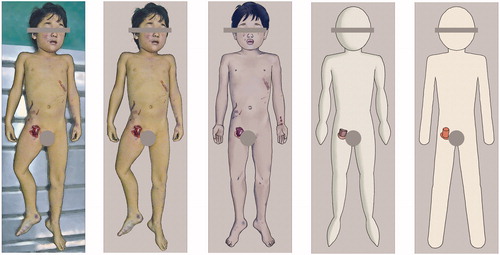

Case 3: Five patterns of illustration were developed: Realistic (to include background information or not), Characteristics and Schematics (medium-low level of detail or very low level of detail). All illustrations utilised Shadow colouring ().

The Realistic illustrations in Case 1 were divided into two options: a picture that included Shadow colouring, or one with just the outline. This was to determine whether the level of detail (i.e. the level of Shadow colouring) affected the amount of information gathered from the picture. As mentioned above, Shadow colouring is an important factor in expressing information in a picture. As in Case 1, Cases 2 and Case 3’s Realistic and Schematics illustrations had two levels of detail. In the Realistic illustration, we focussed on post-mortem positions. If the post-mortem position was not clearly expressed (i.e. it was unclear which side was on the ground), we could not collect the necessary information, as the wound’s direction and depth are critical. Thus, we tried to include this point for Realistic illustrations. The Schematics illustrations had a wider range of possible detail when compared to the other variables; there was concern that the illustrations may therefore be influenced by each creator’s discretion and individual character. Consequently, we adopted two levels of expression: medium low and very low.

This study involved the creation and utilisation of 14 medical-legal illustrations. These were created by two illustrators who had training during their master’s course in the Fine Arts. All processes were conducted in Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator.

Accuracy of medical-legal illustrations’ details

We conducted questionnaire surveys for forensic doctors to confirm the accuracy of the medical-legal illustrations and to gather impressions from a specialist’s point of view (Haragi, Rutsuko, Tsuyoshi, & Kiuchi, Citation2019). Seventeen forensic doctors participated and were asked about which illustration type is the most suitable to deliver accurate information (see Haragi et al., Citation2019). After gathering the data, we conducted a chi-square test.

Case 1 (n = 17): A chi-square test of independence was conducted to compare the illustration description degree: Realistic (including shadow; n = 9, 53%); Realistic (only outline; n = 1, 6%); Characteristics (n = 7, 41%); and Schematics (very low detail; n = 0, 0%). A significant interaction was found (χ2 (2) = 6.118. p < .05). However, no significant interaction between Realistic outline (including shadow) and Characteristics were found.

Case 2 (n = 17): A chi-square test of independence was conducted to compare the degree of detail and colouring; Realistic (including background information; n = 4, 23%); Realistic (not including background information; n = 1, 6%); Characteristics (n = 8, 47%); Schematics (medium-low detail; n = 3, 18%); and Schematics (very low detail; n = 1, 6%). A significant interaction was found (χ2 (4) = 9.765. p < .05).

Case 3 (n = 17): A chi-square test of independence was conducted to compare the degree of detail and colouring; Realistic (including background information) (n = 1, 5.9%); Realistic (not including background information; n = 6, 35.3%); Characteristics (n = 10, 58.8%); Schematics (medium-low detail; n = 0, 0%); and Schematics (very low detail; n = 0, 0%). A significant interaction was found (χ2 (2) = 7.176. p < .05).

Barring Case 1, Cases 2 and 3 indicated that Characteristics is the most suitable to deliver accurate information while also reducing mental stress factors due to a moderate depth of detail. In Case 1, the illustrations were expressed in black and white and contained less information compared to those expressed in colour. Realistic (including shadow) was supported by the forensic doctors; several doctors noted that wound colour is important to estimate the depth and Shadow colouring is important to determine a wound’s state.

Analysis methods

First, the most important data variable is how the mock jurors’ felt when they examined a medical-legal illustration. Therefore, to estimate the mock juror’s feeling, we adapted The Juror Negative Affect Scale (JUNAS; Bright & Goodman-Delahunty, Citation2006), which can be used to calculate negative feelings across four subscales (Disgust, Sadness, Anger and Fear/Anxiety). This scale is comprised of 30 items as follows: Disgust consists of five items (Disgusted, Repulsed, Disturbed, Revolted and Shocked); Sadness consists of six items (Unhappy, Sad, Discourage, Miserable, Gloomy and Helpless); Anger consists of eight items (Angry, Annoyed, Resentful, Bitter, Furious, Bad tempered, Hostile and Irritable); and Fear/Anxiety consists of eleven items (Tense, Shaky, On edge, Panicky, Uneasy, Restless, Nervous, Anxiety, Distressed, Upset and Afraid). All subscales utilised a 5-point scale from Not at all to Extremely and involved four steps. First, mock jurors checked their feelings before beginning the study. Second, participants read information about Cases 1 to 3. Thirdly, they chose which two illustrations they believe to be the most suitable and least suitable to use at a real trial. Finally, they check the JUNAS scale to determine their emotional state after they have examined the two images that they had just chosen.

Four JUNAS measurement results were utilised to calculate each step’s score (minimum 30 – maximum 150). Step 2, 3 and 4’s scores were subtracted from step 1’s score for each, and the resulting number was used (all of the item scores have a minimum of −120 and a maximum of 120; the four subscales have a range as follows; Disgust –20 to 20; Sadness –24 to 24; Anger –32 to 32; and Fear/anxiety –44 to 44). Higher numbers indicated strong negative feelings and lower numbers indicated weak negative feelings.

In each case, to determine which illustration had the necessary amount of detail for a real trial, this study first adopted a chi-square test. In order to determine whether positive differences emerged between the suitable and unsuitable illustrations, we then adapted the independent t-test to find differences of JUNAS average score. Additionally, to determine differences of depth of detail, this study adapted an independent t-test for the top two image types.

Selection of participants as mock jurors

This study needed to be cautious when selecting survey participants, because the medical-legal illustration may cause secondary traumatic stress and PTSD. In most studies, participants would be chosen randomly from citizens over 18-year old who may be chosen as jury members. However, considering the mental invasiveness of the illustrations, we chose university students who were majoring in a health science course. A health science course was chosen as research subjects may have significance for public health. Additionally, we assumed that they would be more open to this type of research as they study human bodies and anatomy. We estimated that they have a higher tolerance for post-mortem cases. We conducted the survey as a part of the ‘Information literacy’ class in the Department of Health Sciences, Saitama Prefectural University.

Survey methods

The study was carried out on 9th July 2019. We introduced the research aim and procedure to each participant. Those who felt uneasy at viewing post-mortem cases left, and the remaining students completed informed consent forms. We then distributed a questionnaire and the sheets of illustrations (see the Appendix questionnaire in the online supplemental data). The students checked the JUNAS scales before beginning the study, after this they examined the illustration sheets (including description of the details of the cases) and answered the questionnaire.

Results

Participant demographics and descriptive statistics

Thirty-seven college students (male: 15, female: 22) completed the survey. Unfortunately, some people dropped out due to not wanting to examine the illustrations, and some forgot to check the JUNAS scales: the effective number of people was 26 (male: 8, female: 18). Descriptive statistics as follows: JUNAS total records average = 46.58 (SD = 23.634); Disgust subscale average = 7.88 (SD 4.43); Sadness subscale average = 8.81 (SD = 4.622); Anger subscale average = 10.29 (SD = 5.207); and Fear/anxiety subscale average = 18.38 (SD = 11.046).

Results analysis

Case 1

① A chi-square test of independence was conducted to compare the most suitable illustration to use in a real trial: Realistic (including shadow; n = 7, 26.9); Realistic (only outlines; n = 4, 15.4%); Characteristics (n = 14, 53.8%); and Schematics (very low detail; n = 1, 3.8%). A significant interaction was found (χ2 (3) = 14.308. p < .01). Characteristics illustrations are more likely to be suitable than Schematics and Realistic (outline only) illustrations. Additionally, Realistic (include shadow) illustrations are more likely to be suitable than Schematics. However, no significant interaction between Realistic with outline (including shadow) and Characteristics illustrations were found. A chi-square test of independence was conducted to compare the most unsuitable illustration to use in a real trial: Realistic (including shadow; n = 7, 26.9%); Realistic (only outline; n = 2, 7.7%); Characteristics (n = 1, 3.8%); and Schematics (very low detail; n = 16, 61.5%). A significant interaction was found (χ2 (3) = 21.692. p < .01). Schematics illustrations are more likely to be unsuitable than Characteristics and Realistic (only outline) illustrations. However, no significant interaction between Realistic outline (including shadow) and Characteristics illustrations was found.

② An independent t-test was conducted to compare the JUNAS score when examining the most suitable illustrations and the unsuitable one; suitable average (n = 26): 16.77 (SD = 18.169); unsuitable average (n = 26): 12.15 (SD = 26.128); Independent t-test, t (50) = 0.739 n.s. (p > 0.05).

③ After the initial t-test, we conducted another independent t-test to determine whether differences in detail affects the JUNAS score for the top two suitable and unsuitable illustrations. The top two suitable illustrations were Characteristics and shadowed Realistic illustrations: Characteristics (n = 14) average: 16.29 (SD = 22.092); Realistic (include shadow; n = 7) average: 18.861 (SD = 7.515); and Independent t-test, t (19) = 0.770 n.s. (p > 0.05). The top two deemed unsuitable were Schematics and shadowed Realistic illustrations: Schematics (n = 16) average 3.38 (SD = 21.338); Realistic (include shadow; n = 7) average 33.43 (SD =19.873); and Independent t-test, t (21) = 0.005, p < .01.

Case 2

① A chi-square test of independence was conducted to compare the most suitable illustration to use in a real trial: Realistic (including background information; n = 1, 3.8%); Realistic (not including background information; n = 6, 23.1%); Characteristics (n = 15, 57.7%); Schematics (medium-low detail; n = 4, 15.4%); and Schematics (very low detail; n = 0, 0%). A significant interaction was found (χ2 (3) = 16.769. p < .01). Illustrations utilising Characteristics were more likely to be suitable than Realistic (include background information) and Schematics (very low detail) illustrations. However, no significant interaction between Realistic (not include background information) and Characteristics illustrations was found. A chi-square test of independence was conducted to compare the most unsuitable illustration to use in a real trial: Realistic (including background information; (n = 17, 65.4%); Realistic (not including background information; n = 1, 3.8%); Characteristics (n = 0, 0%); Schematics (medium-low detail) (n = 0, 0%); and Schematics (very low detail; n = 8, 30.8%). A significant interaction was found (χ2 (2) = 14.846. p < .01). Realistic (include background information) illustrations are more likely to be unsuitable than Characteristics, Schematics (medium-low detail) and Realistic (not include background information) illustrations. However, no significant interaction between Realistic (include background information) and Schematics (very low detail) were found.

② An independent t-test was conducted to compare the JUNAS score when examining most suitable and unsuitable illustrations: the suitable average was (n = 26): 10.08 (SD = 20.284), the unsuitable average was (n = 26): 13.15 (SD = 24.142), and the independent t-test was t (50) = 0.621 n.s. (p > 0.05).

③ After the initial t-test, we conducted another independent t-test to determine whether differences of details affect the JUNAS score for the top two suitable and unsuitable illustrations. The two deemed Suitable were the Characteristics and Realistic (not including background information) illustrations: Characteristics (n = 15) average 13.27 (SD = 21.382); Realistic (not including background information) average 7.5 (SD = 24.04); and Independent t-test, t (19) = 0.596 n.s. (p > 0.05). Those deemed unsuitable were Realistic (including background information; (n = 17), average: 21.76 (SD = 21.194); Schematics (very low detail; n = 8): average −4.50 (SD = 22.69); and Independent t-test, t (23) = 0.010, p < .05.

Case 3

① A chi-square test of independence was conducted to compare the most suitable illustration to use in a real trial: Realistic (including background information; n = 2, 7.7%); Realistic (not including background information; n = 10, 38.5%); Characteristics (n = 10, 38.5%); Schematics (medium-low detail; n = 4, 15.5%); and Schematics (very low detail; n = 0, 0%). A significant interaction was found (χ2 (3) = 7.846. p < .05). Realistic (not including background information) and Characteristics illustrations were more likely to be suitable than Schematics (very low detail) and Realistic (including background information) illustrations. However, no significant interaction between Realistic (not including background information) or Characteristics and Schematics (medium-low detail) illustrations were found. A chi-square test of independence was conducted to compare the most unsuitable illustration to use in a real trial: Realistic (including background information; n = 8, 30.8%); Realistic (not including background information; n = 0, 0%); Characteristics (n = 1, 3.8%); Schematics (medium-low detail; n = 0, 0%); and Schematics (very low detail; n = 17, 65.4%). A significant interaction was found (χ2 (2) = 14.846. p < .01). Schematics (very low detail) and Realistic (include background information) illustrations were more likely to be unsuitable than Characteristics, Realistic (not include background information) and Schematics (medium-low detail) illustrations. However, there was no significant interaction between Schematics (very low detail) and Realistic (include background information) illustrations.

② An independent t-test was conducted to compare the JUNAS score when examining the most suitable and unsuitable illustrations: suitable average (n = 26): 25.73 (SD = 24.468), unsuitable average (n = 26): 15.15 (SD = 36.248), and Independent t-test, t (50) = 0.223 n.s. (p > 0.05).

③ After the initial t-test, we conducted another independent t-test to determine whether differences of detail affect the JUNAS score for the top two suitable and unsuitable illustrations. Those deemed suitable were Realistic (not including background information) and Characteristics illustrations: Realistic (not including background information; n = 10) average: 26.3 (SD = 25.863); Characteristics (n = 10) average: 19.26 (SD =24.006); and independent t-test, t (23) = 0.007, p < .01. Those deemed unsuitable were Schematics (very low detail) and Realistic (including background information) illustrations: Schematics (very low detail) (n = 17) average: 0.53 (SD = 31.181); Realistic (including background information; n = 8) average: 39.75 (SD = 29.567); and Independent t-test, t (21) = 0.005, p < .01.

Discussion

For statistic ①’s result, all three cases revealed that Characteristics illustrations contain the most suitable depth of detail for a real trial. This result reflected the findings from the forensic doctors, excluding Case 1 for which the forensic doctors chose the Realistic illustration (including shadow). We predicted that mock jurors would want less information than doctors who are accustomed to viewing such pictures in order to reduce the possibility of secondary trauma stress. We consider this result as the most important for establishing guidelines for efficient medical-legal illustrations. ‘Characteristics’ is an adjective and it is therefore subjective: it will be difficult to depict the same level of Characteristics for each post-mortem case. Thus, to strengthen this result, a range of Characteristics details will have to be defined and include classifications by wounds, sex and age, concentrating on the details that may affect the jurors’ impression.

Concerning the second most suitable illustration in all three Cases, there were some differences in preference between forensic doctors and mock jurors. Case 1’s second top choice was Realistic (include shadow) illustrations, while Case 2 and 3’s was Realistic (not include background information) illustrations. In Case 1, this reflects the results from the forensic doctors. As mentioned above, black and white colouring makes it difficult to express the correct information, such as the depth of wounds: this may affect the assessment of the severity of the case. In this study, we did not question why participants came to the conclusions that they did, but this similar result may indicate that if medical-legal illustration needs to utilise only black and white, using Realistic (including shadow) illustrations would be recommended. Additionally, Case 2 and 3’s result revealed another viewpoint that indicates a difference between the Realistic (including background information) and Realistic (not including background information) illustrations. Forensic doctors seemed less concerned about whether background information was included or not. On the other hand, the participants preferred the illustrations that did not include background information, and the illustrations with background information were chosen as unsuitable. Moreover, Case 2’s and 3’s Realistic (including background information) illustrations’ JUNAS total score was higher than the other variables. We estimate that this preference may indicate that background information causes mental stress, as the picture may include possible distressing information (e.g. the coroner’s table). Previous studies indicate that unusual situations may affect emotions (Grady et al., Citation2018). We can assume that examining post-mortem cases is not usual for the participants and real jurors: the accumulation of unusual factors may affect the individual’s frame of mind.

On the contrary, all of Case 1’s results of details for real trials indicated that Schematics and Realistic illustrations were unsuitable to describe post-mortem cases. In this study, however, participants did not prefer Schematics illustrations: Schematics’ JUNAS total score was the lowest out of all the scores. This indicated that Schematics illustrations did not invoke strong emotions in the participant: therefore, this level of detail for illustrations may be adequate for criminal cases, as it may reduce the possibility of punitive judgments. However, Schematics may not adequately express important information for jurors. Forensic doctors mentioned that Schematics illustrations did not provide enough information about the wound’s position, depth and other important data. To summarise these results, Schematics illustrations were deemed unsuitable to use as a medical-legal illustration.

Further, the result of the Schematics and Realistic (including background information) illustrations as unsuitable revealed participants were roughly divided into two types: those who dislike Realistic (including background information) illustrations, and those who disliked Schematics. This division revealed Case 3’s t-test result as the top two unsuitable illustrations. All cases suggested significant interaction between Realistic (including background information) and Schematics illustrations.

In this area of research, this is the first investigation of medical-legal illustrations for mock jurors. A limitation is that this research did not gather enough participant demographic data and did not ascertain which factors caused the preferences demonstrated. If the reasoning behind the preferences were to be explored, it could suggest the motives for some participants disliking the Realistic illustrations; therefore, it may be possible to avoid suffering from secondary trauma stress and PTSD.

The result ③ of Case 3 was particularly interesting. There were significant interactions between Schematics (very low detail) illustrations’ JUNAS total score, which was depicted as unsuitable, and the Realistic (not including background information) illustration, which was depicted as suitable. Other cases did not inspire the same result; thus, we can presume that this outcome may have differed from the others due to Case 3’s victim. Previous studies revealed that cases involving children and the elderly cause more mental stress and emotions in jurors (Victoria Estrada-Reynolds & Nuñez, Citation2016) than others. This perception may explain certain results in this study. Moreover, the two types of Realistic illustrations divided results between suitable and unsuitable. This result may suggest that too much realism is unendurable, but a certain level of detail and information is needed to understand the details of the crime.

Conclusion

From these results, the following points were revealed. First, forensic doctors and participants were more likely to choose Characteristics illustrations as the most suitable method of displaying the details of a graphic case. Second, Realistic (not including background information) illustrations are more likely to be acceptable as a suitable technique compared to Realistic (including background information) illustrations. Thirdly, Schematics illustrations indicated a low JUNAS score; otherwise, participants and forensic doctors were more likely to choose as an unsuitable method. This is a significant step forward in this research area, and also a step forward for our aim to establish guidelines for efficient medical-legal illustrations.

In the future, more investigations are needed to strengthen the validity of the findings of this study. For example, this study only investigated forensic doctors and mock jurors, and therefore, we need additional legal professionals’ opinions (including lawyers, defendants and judges). Additionally, we need to recreate more suitable medical-legal illustration classifications. Furthermore, in order to confirm the factors that most influence mental stress and emotions, another mock juror study is needed.

This study had some limitations. First, the participant group sample is small. There are two reasons for this: one is that this research may affect the mental health of participants and therefore is it necessary to be careful while choosing participants, and additionally, some people forgot to check the JUNAS scales. The former can only be solved by continuing to pay close attention to the chosen individuals, and the latter needs a clearer questionnaire and explanation.

Second, there were no significant interactions in ②’s result. Each score’s standard deviation had a wide range, and from this we estimated that the perception gap affects this research result. Therefore, marks are scattered and difficult to comprehend.

Third, the study’s participants were familiar with this subject because they were studying health science as their degree. This would not be the case for every person who is chosen as a jury member, so a more generalisable sample is needed and have to consider that differences of participants national origins and cultures which may affect for differences of impression.

Fourth, this study investigated only three images. In a real trial, members of the justice system deal with many different criminal cases. As such, research needs to explore other post-mortem cases to determine different factors that may cause secondary traumatic stress and PTSD.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (3.7 MB)Acknowledgements

First, the authors acknowledge the contributions of participating Honma Mieko who associate professor of Department of Health Sciences, Saitama Prefectural University and students. Second, the authors are grateful for the assistance received from Professor Hirotarou Iwase, who permitted access to the database and approved this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available as they include personal data; however, they are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Antonio, M.E. (2008). Stress and the capital jury: How male and female jurors react to serving on a murder trial. Justice System Journal, 29, 396–407. doi:10.1080/0098261X.2008.10767903

- Bertrand, L.D., & Paetsch, J.J. (2008). Juror stress debriefing: A review of the literature and an evaluation of a Yukon program. Calgary, AB: Canadian Research Institute for Law and the Family.

- Bornstein, B.H., Miller, M.K., Nemeth, R.J., Page, G.L., & Musil, S. (2005). Juror reactions to jury duty: Perceptions of the system and potential stressors. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 23, 321–346. doi:10.1002/bsl.635

- Bright, D.A., & Goodman-Delahunty, J. (2006). Gruesome evidence and emotion: Anger, blame, and jury decision-making. Law and Human Behavior, 30, 183–202. doi:10.1007/s10979-006-9027-y

- Chamberlain, J., & Miller, M.K. (2008). Stress in the courtroom: Call for research. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 15, 237–250. doi:10.1080/13218710802014485

- Chamberlain, J., & Miller, M.K. (2009). Evidence of secondary traumatic stress, safety concerns, and burnout among a homogeneous group of judges in a single jurisdiction. Journal of American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 37, 214–224.

- Cheung, M. 2016. Ex-juror diagnosed with PTSD says psychiatric help should be available after trials [Online]. CBC. Retrieved August 13, 2019, from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/jury-murder-trials-justice-court-ontario-ptsd-trauma-1.3796520

- Dabbs, M.O. (1992). Jury traumatization in high profile criminal trials: A case for crisis debriefing? Law and Psychology Review, 16, 201–216.

- Dunn, T. 2018. Juror diagnosed with PTSD launches $100K lawsuit against 2 governments [Online]. CBC. Retrieved August 13, 2019, from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/juror-trauma-lawsuit-1.4543248

- Flores, D.M., Miller, M.K., Chamberlain, J., Richardson, J.T., & Bornstein, B.H. (2008). Judges’ perspectives on stress and safety in the courtroom: An exploratory study. Court Review, 45, 76–89.

- Grady, R.H., Reiser, L., Garcia, R.J., Koeu, C., & Scurich, N. (2018). Impact of gruesome photographic evidence on legal decisions: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 25, 503–521. doi:10.1080/13218719.2018.1440468

- Haragi, M., Rutsuko, Y., Tsuyoshi, O., & Kiuchi, T. (2019). Interviewing forensic specialists regarding medical-legal illustration methods to replace gruesome graphic evidence. Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine, 9, 1–8. doi:10.1080/17453054.2019.1687287

- Houts, P.S., Doak, C.C., Doak, L.G., & Loscalzo, M.J. (2006). The role of pictures in improving health communication: A review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Education and Counseling, 61, 173–190. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2005.05.004

- Kaplan, S.M. (1985). Death, so say we all. Psychology Today, 19, 48.

- Kaplan, S.M., & Winget, C. (1992). The occupational hazards of jury duty. The Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 20, 325–333.

- Lonergan, M., Leclerc, M.-È., Descamps, M., Pigeon, S., & Brunet, A. (2016). Prevalence and severity of trauma- and stressor-related symptoms among jurors: A review. Journal of Criminal Justice, 47, 51–61. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2016.07.003

- Mader, S., Wilson-Pauwels, L., Nancekivell, S., Lax, L.R., Agur, A.M., & Mazierski, D. (2005). Medical-legal illustrations, animations and interactive media: Personal injury lawyers' perceptions of effective attributes. Journal of Biocommunication, 31, 6–17.

- Miller, L. (2008). Juror stress: Symptoms, syndromes, and solutions. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 10, 203–218.

- Miller, M.K., & Bornstein, B.H. (2004). Juror stress: Causes and interventions. Thurgood Marshall Law Review, 30, 237–269.

- Nanbu, S. (2015). Saibann-in no sutoresu to kueki ni kann suru ichi kousatsu [Stress of jurors and discussion of their hard work]. The bulletin of the Yokohama City University. Humanities and Science, 66, 37–73.

- National Center for State Courts. 1998. Through the eyes of the juror: A manual for addressing juror stress (NCSC publication no. R-209). Williamsburg, VA: National Center for State Courts.

- Oliver, E., & Griffitt, W. (1976). Emotional arousal and ‘objective’ judgment. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 8, 399–400. doi:10.3758/BF03335179

- Pauwels, L. 2005. A theoretical framework for assessing visual representational practices in knowledge building and science communications. In L. Pauwels (Ed.), Visual culture of science: Rethinking representational practices in knowledge building and science communications. Hanover, New Hampshire: University Press of New England.

- Salerno, J.M., & Bottoms, B.L. (2009). Emotional evidence and jurors' judgments: The promise of neuroscience for informing psychology and law. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 27, 273–296. doi:10.1002/bsl.861

- Scheltema, E., Reay, S., & Piper, G. (2018). Visual representation of medical information: The importance of considering the end-user in the design of medical illustrations. Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine, 41, 9–17. doi:10.1080/17453054.2018.1405724

- Strong, J., & Erolin, C. (2013). Preference for detail in medical illustrations amongst professionals and laypersons. Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine, 36, 38–43. doi:10.3109/17453054.2013.790793

- Victoria Estrada-Reynolds, K.A.S., & Nuñez, N. (2016). Emotions in the courtroom: How sadness, fear, anger, and disgust affect jurors’ decisions. Wyoming Law Review, 16, 343–358.

- Whalen, D.H., & Blanchard, F.A. (1982). Effects of photographic evidence on mock juror judgement. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 12, 30–41. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1982.tb00846.x