Abstract

Images in medical communication are appreciated by both professionals and patients, but we know little about how they are actually used in clinical practice and in the learning processes of patients. This qualitative study investigates the use and the meaning potential of two different types of heart images: the hand-drawn doctor’s sketch and the digital illustration from the web. The analysis starts with how these are recontextualised in social media, tracks them back to their original contexts and finally explores their material resources. The analytical perspective is that of social semiotics and multimodal discourse and interaction analysis. While the hand-drawn sketch is recontextualised as a witness of the specific consultation, the digital illustration is used to focus on the heart defect as such. It is also shown how the act of drawing works as a means for framing and structuring the consultation, slowing down the pace and reducing context and detail and thus focussing on what is uniquely relevant. While the digital and more realistic illustration is technically neutral and objective and is free from unique context, the drawing on paper is physically tied to its context of origin, which is also its main resource.

Background

This study concerns how medical images are used in actual health literacy practices, by patients and doctors. Health literacy practice refers to social learning activities about health and illness, situated in time and place, and in which both patients and doctors engage – although to a large extent within different framings (Dray & Papen, Citation2004). Kearns et al. (Citation2020) found that visual representations were appreciated by 99% of the patients, and most of all by patients who were to undergo complicated surgery. Kearns (Citation2019) found that 92% of asked surgeons saw drawing as a natural part of patient communication. Kearns et al. (Citation2022) show that over 90% of New Zealand doctors (96% of surgeons) draw in their clinical practice. According to their survey, drawing was used for building rapport, documentation, collegial communication, orienting pathology specimens, explaining the surgery, and for supporting informed decision-making.

Scheltema et al. (Citation2018) asked clinicians as well as patients to choose between images with different levels of realism and found that all users, but especially patients, preferred realistic images. Similar results were shown in a study which particularly focussed on images of the heart, and in which lay persons (but not patients) as well as professionals preferred images with a high level of detail (Strong & Erolin, Citation2013).

In sum, we know that the use of images in medical consultation and information is appreciated by both professionals and patients and that drawing is widely practised, but the knowledge of how doctors and patients actually use images, and how these images afford different kinds of meaning to be made, is sparse. The present study deals with authentic medical illustrations from the perspective of actual use in multiple contexts. A key concept for these processes is recontextualisation, i.e. the moving of a semiotic artefact (a text, image or utterance) from one context to another. Recontextualisation changes the meaning of the artefact, but it also highlights its resources and affordances. Our starting point is that images with different affordances are recontextualised differently. The study contributes to the field of visual communication in medicine by searching for clues to the meaning-making potentials of different types of medical images in authentic contexts, and by relating the use of images to the communicative practices (predominantly linguistic) that they are a part of. This social practice perspective (Dray & Papen, Citation2004) reaches beyond the consultation room and the actions of professional caregivers and enables us to address questions of learning in ways that experimental or survey-based studies cannot.

Aim and analytic focus

The aim of the study is to explore how fundamentally different pedagogical images of the heart – doctor’s hand-drawn sketches and digital illustrations from medical websites – work as tools for communication and learning. The analysis is made both with respect to the material affordances of the images and to their actual use in context. Hand-drawn and digital images are compared regarding (1) functions when recontextualised, (2) function in their original context, and (3) material resources for meaning-making.

The present study is based on linguistics, and more specifically the field of multimodal discourse analysis (e.g. Kress & van Leeuwen Citation2006; Norris Citation2004). Here, the basic assumption is that communication is multimodal, i.e. accomplished by the use of several modes (or resources), where language (often) is one. Discourse should be understood as meaning-making in context, through text and talk (Foucault, Citation1980). Besides multimodality, a key perspective in discourse analysis is that of dialogue or interaction. Every utterance is understood in relation to previous and subsequent utterances. From earlier research in multimodal discourse analysis, we know that visual meaning-making is just as conventional as linguistic communication. Images make meaning in “grammatical” ways, and there are conventions which set the frames for interpretation (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2006). We also know that there is no “monomodal” communication. Instead, all verbal encounters have visual, embodied and acoustic dimensions, and artefacts often play a key role (Norris, Citation2004). Finally, we know that health communication is not only about doctor-and-patient encounters. Through the Internet, patients have gained wide resources for building knowledge together, in forums and in social media (e.g. Bellander & Landqvist, Citation2020; Melander, Citation2019).

In relation to medical practice, the linguistic, multimodal and interactional perspective can provide insights regarding how the different representations are used, why they are appreciated and if they are filling different functions, depending on the type of representation and context. These questions call for deeper and more detailed analyses into smaller sets of data, i.e. cases. As stated by O’Brien et al. (p. 1245, Citation2014), qualitative research contributes to knowledge “by describing, interpreting and generating theories about social interactions as they occur in natural, rather than experimental situations”.

Data and methods

The case study presented is based on data from the linguistic research project Health Literacy and Knowledge Formation in the Information Society. In focus are pregnant couples and parents dealing with a diagnosis of a heart defect in their foetus or child. Data was collected by starting with pregnant couples who consulted one of the few specialised clinics in Sweden, and who accepted to participate. They led us to relevant networks and digital forums. During a three-year period (2013–2016), a database was set up based on the various communicative activities of about 25 couples: recorded consultations, interviews, information texts, blogs, posts in discussion forums and social media. In a number of studies, different contexts and practices were explored. For this study, we have chosen to focus on the recontextualisations on Instagram of two different types of images: the hand-drawn sketch and the digital illustration. We analyse the role and function of the images, and then trace them back to their original situations. Finally, we analyse the material resources of the images in order to find explanations for the differences found.

The analysis is qualitative and theory-driven. Only a few postings, recordings and images are analysed. For the earlier studies in the project, the large database has been coded thematically (using the software Atlas.ti), which has made it possible to find instances where images are used or talked about. Images were used in all recorded consultations, and most of these were hand-drawn. Analyses of the consultations have shown that they share a firm structure, which is supported by the drawing of the image (Bellander & Karlsson, Citation2019). Based on these observations, excerpts have been chosen in order to illustrate what can be understood as a routine. Digital illustrations of various kinds are commonly used in our data from blogs and social media. The examples used in this study were originally produced for the Swedish official medical information website 1177 Vårdguiden (‘1177 Care Guide’). O’Brien et al. (Citation2014) discuss standards for reporting qualitative research. Their recommendations have been observed.

Recontextualisation is analysed with a focus on the roles played by different modalities (image, verbal text), in relation to communicative actions on different levels (Norris, Citation2004). When analysing actions, comments are an important resource. From an interactional perspective, responses are the key to understanding the function of an utterance. This approach is also applied in the analysis of examples from consultations and interviews. Analytical tools for understanding the material resources of the different types of images are drawn from multimodal social semiotics (van Leeuwen, Citation2005, Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2006). Social semiotics understands meaning as created in the process of representation; thus, it is a constructivist perspective. A main assumption is that the choice of a sign is motivated: i.e. the choice of drawing by hand or using a ready-made illustration is not made by chance or accident, but is based on the potential, or affordances, of the material resource (van Leeuwen, Citation2005).

The data collection was approved by the Local Ethical Vetting Committee in Uppsala (reg. no. 2015/151). Informed consent was received from all recorded and interviewed participants and cited bloggers. Posters on Instagram have been anonymised. Comments are left out but are referred to. All verbal examples have been translated from Swedish.

Results

Our findings are presented, starting from the recontextualisations of the different image types in social media. The two image types are then traced back to their original contexts and finally analysed in terms of their material resources for making meaning.

Recontextualisation

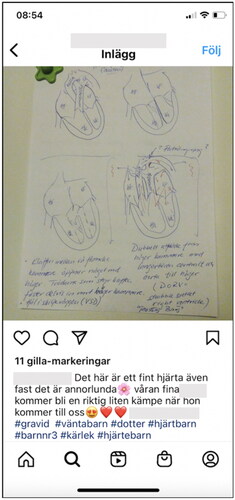

shows a representative example of the first type of image photographed and posted on Instagram. The green star-shaped magnet in the left corner suggests that the hand-drawn sketch is hanging on a magnet board or a refrigerator door. The verbal text in the post is evaluative and emotive. It reads: “This is a nice heart even though it is different. Our beautiful [name] will be a real little fighter when she comes to us”. Nothing is said verbally about how the poster has learned about the heart defect. The experience of attending a medical consultation is thus narrated only by the photographed hand-drawn sketch. The image also conveys information about the current diagnosis, for readers who are able to understand the drawing. Thus, while the image performs the overall action of telling about the learning of the heart defect, the verbal text complements this by conveying emotions in relation to this experience. The verbal text also provides intertextual references, through nine hashtags linking the post to other posts. One hashtag refers to the Instagram account #heartchild. The others refer more generally to pregnancy: i.e. #pregnant, #expectingachild and #daughter.

The comments following the post responded to the fact that the parents-to-be have found out about the expected baby’s heart failure. One person even recognised the drawing style, and wrote that she has been to the same doctor. This person also commented on the specific failure (which was only described in the image), and shared her own experiences with the same diagnosis.

shows an Instagram post including an image of a digital illustration of a heart with a defect, and for comparison: a smaller, healthy heart in the left corner. This example shows a different kind of recontextualisation.

Figure 2. A digital illustration from www.1177.se on Instagram

In this composition, the roles of image and language are reversed. The written text tells us about the poster’s child, who was born with a named and explained heart defect: “My youngest son was born with a heart defect which is called transposition, where the pulmonary artery and the aorta have switched places”. The post was made on Valentine’s Day (in Swedish Alla hjärtans dag, ‘The day of all hearts’), and the poster wanted to raise awareness about heart defects in children. The image can be seen as a resource for creating a more general focus on the heart defect as such, and less on the individual family and their experience. The post received one comment in the form of three hearts. The verbal text includes ten hashtags, one of which refers to the baby’s name. The remaining nine all refer to the heart defect, for example: #transposition, #allchildrensheartmonth, #theheartchildassociation.

The analysis reveals the role of the images in the different recontextualisations. The hand-drawn sketch was used to tell the story about a specific consultation, child and heart defect. The digital image communicated in more general terms, informing about a type of heart defect and raising awareness of its existence. The hashtags contributed to the different orientations of the posters: individual experiences within the context of pregnancy vs. the heart defect as such in relation to awareness raising.

Original contexts

From previous studies in the project, we know that doctors use visual meaning-making together with verbal talk (Bellander & Karlsson, Citation2019, Nikolaidou & Bellander, Citation2018). In the group interview, one of them explained that this is due to a need to “track and sort” both what kind of information and how much information the couple are receptive to. Thus, the doctor motivated drawing as a tool for creating a focus and establishing a joint perspective that reduces context and draws attention to the anatomical features of the actual heart. Ready-made illustrations and three-dimensional models were rejected, with the motivation: “I don’t use them. I see a problem with too much information being transferred in a very short time.” Drawing helps with the selection of what information is important and relevant. All interviewed couples in our data expressed appreciation for the drawing session. By thematically analysing all 25 interviews we have found three main reasons:

First, the couples found that the drawing and the verbal speech interacted and facilitated their understanding. Some pointed at the slow pace caused by the drawing. A woman said: “he took his time when he drew” which indicates that the slow tempo provided the couples with time to process and understand the information. Some couples told us that the drawing session enabled them to absorb and remember the information to an extent that they were able to pass the information on to others: One woman said: “I feel like I am an expert on how the heart functions. When calling the family I say: ‘this is what the heart looks like and this is what it should look like’”.

Second, the couples appreciated that the hand-drawn sketch was personal in the sense that it only contained information that was relevant to them. They appreciated that they got to bring the sketch home to keep as a memory and/or to consult in order to recall information. A man said: “and then I kept these sketches and I have looked at them again from time to time”.

Third, the couples described a feeling of being secure, calm and well taken care of that they derived from the drawing session. One woman recalled entering the consultation filled with negative feelings. She expressed the relief she felt when the doctor’s drawing helped her to focus on the concrete physical functions of the foetus’ heart: “That [the baby] would be in a wheelchair, unable to talk, you know all of that was repeating in my head. My thoughts were stuck. That he drew images; that was very good”. Another woman pointed to the relief she felt listening to the doctor and seeing what he pointed out during the drawing session: “He drew and he also wrote down what he had seen and what he thought, and he underlined that this is healthy and that, well one sits there and one is holding back one’s tears and it is just such a nice feeling”.

Thus, choosing to draw – instead of talking only, or using ready-made illustrations or models – was motivated by the professional’s experience of being able to reduce complexity, to focus on anatomy and the known near future (i.e. possible surgery) and getting the couple to follow the explanation and grasp the situation. The couples appreciated the drawing sessions as they found the information given by an image and talking in combination, easy to understand. Moreover, the sketches were personal and the consultation provided them with a focus and a feeling of comfort. This effect was possible since drawing is a material and situated process, which organises the encounter and the talk, both spatially and sequentially.

In the following, we use three transcribed excerpts from doctor consultations with pregnant couples to show how the act of drawing and the sketch as an artefact function in interaction. The talks took place in an examination room at the hospital where the doctor had just examined the foetus using ultrasound. Double brackets mark contextual comments.

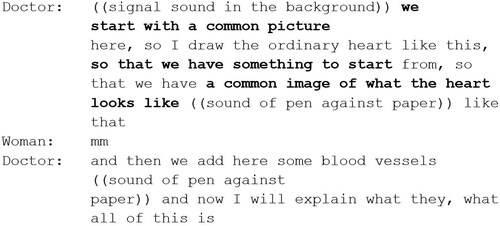

In it is shown how the doctor framed the drawing activity as new and different from the preceding examination by grabbing a piece of paper, starting to draw and verbally announcing that they will now start by creating “a common picture”, “so that we have something to start from”, “a common image of what the heart looks like”. These words are made bold. The example shows how the act of drawing oriented all participants to the importance of sharing basic knowledge about the heart.

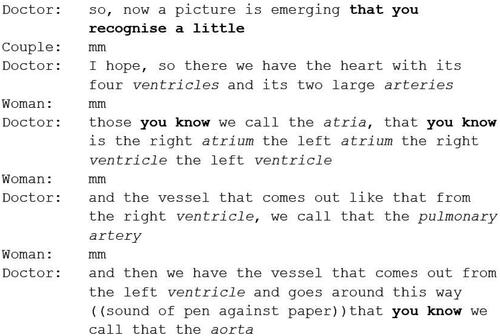

In , from the same consultation, it is shown how the doctor continued explaining by simultaneously drawing and talking. He sought consensus by implying that the information he gave might be (or even is) already known to the couple: “that you recognise a little”. By frequently using the Swedish adverb ju, here translated with the phrase “you know” (marked in bold) while naming the parts of the heart (here in italics), he suggested that the construction and functions of the ordinary heart are (or should be) common knowledge. By doing this, he also suggested that there is new knowledge to come – this information is only the background.

As the talking and the drawing continued, it became clear that the parts of the ordinary heart specifically pointed out by the doctor were the parts which were affected by malformation and that were the focus of treatment and surgery.

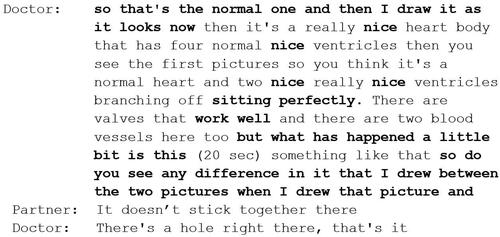

, shows an example from a consultation with a similar structure but with another couple. Here the doctor moved on from drawing the normal heart to drawing the heart of the foetus. This drawing was placed on the same piece of paper. Verbally, the doctor marked the shift from drawing the general, healthy heart to drawing the specific, defective heart by saying “So that’s the normal one and then I draw it as it looks now”. He also guided the couple’s understanding of what is still normal and healthy by labelling these parts as “nice”. Finally, he asked the couple if they could see the differences between the drawings, which they could. Thus, drawing and talking were used together in a pedagogical project, where the couple were guided to draw conclusions from what they saw.

Thus, the act of drawing had the function of a tool for switching from the background to the actual case. By drawing the heart of the foetus, the doctor was able to show that large parts are perfectly normal: “nice”, “sitting perfectly” and “work well”, but then there was the defect. In this case, the doctor lead the couple to see the difference for themselves, and the partner of the pregnant woman noted that there was a space where there shouldn’t be one.

In sum, talking and drawing can both be seen as important tools in the health literacy process of understanding the severity of the defect and possible corrections. The spoken language and the act of drawing and writing were both used for two main tasks: (1) to explain the functions of the heart and (2) to frame and organise the activity (the consultation) and its phases. As for the first task, the spoken language and the drawing were integrated and supported each other. Nothing was drawn that was not explained verbally and vice versa, although the visual information tended to reduce the nuances of what was said verbally. While names for the parts and functions of the heart were mainly introduced through spoken language, the image showed how the different parts of the heart related to each other in terms of proximity and size. As for the second task, the drawing marked the beginning of new phases in the conversation and kept the participants oriented towards the same focus. Spoken language (in relation to what happens on paper) was also used to build a relationship with the couple: it was by language that the doctor guided the couple through the background knowledge of the new and specific information. Language was used for evaluation, to assuring that many parts were “nice” and “work well”. The image, in comparison, was neutral.

The original context of the digital illustration was different in many ways. It was originally produced for the Swedish official medical information website 1177 Vårdguiden (‘1177 Care Guide’) by a professional illustrator. The patient who saw the illustration on the website was probably searching for up-to-date information about common heart defects.

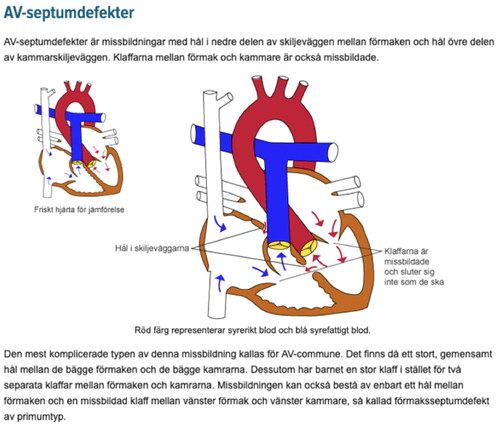

shows the illustration with its original surrounding text: written information about atrioventricular septal defects. On the website, the verbal and visual information could be read in any chosen order. The written text did not comment on or complement the image, but stood alone. In the same way, the image had written components which explained the part and the defects, which made it possible to understand the image without reading the surrounding text. The heart with the defect is the large one. Smaller, in the left corner, is a healthy heart, with the text “Healthy heart for comparison”. Compared to the consultation, where the image and verbal language worked in mutual relation to each other, the site displayed the resources for the reader to choose from. This is said to be typical of multimodal texts in the digital era (cf. Kress, Citation2005).

Material resources

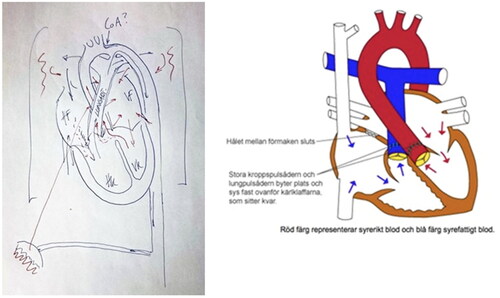

The role that different types of medical images play in health literacy practices can be derived from the meaning potentials that the material affordances of the images have. In , a hand-drawn sketch and a digital illustration are placed side by side.

In comparison, the two images differ when it comes to the degree of evenness and smoothness. The hand-drawn sketch is drawn with an ink pen on white paper and shows corrections and additions. The lines are thin, not mechanically straight. The lines and arrows in the digital illustration are even, smooth and without corrections and additions. While the hand-drawn sketch bears evidence of the work of the doctors’ hand, the digital illustration is spotless and ‘perfect’, with no traces of corrections or of the production process at all.

Another difference relates to the degree of realism. In the hand-drawn sketch, the different parts of the heart are represented in two dimensions, without showing depth or texture. The relative positions and sizes of ventricles, atria, valves, veins and arteries are in focus and these are also marked by letters. Their relative positions and sizes are represented in a more realistic manner, although the sketch as a whole is reduced and schematic. The analytical term for this is technological coding orientation (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2006:165). The digital illustration does not entirely adopt a naturalistic coding orientation, but it is less technological since it represents both depth and texture and also the natural shape of the heart. The texture of the tissue is represented by wavy lines, and the arteries are made three-dimensional. Although not realistic compared to many other medical illustrations, the digital illustration is richer in detail compared to the hand-drawn sketch, showing the thickness and surface properties of the tissue.

Furthermore, in the hand-drawn sketch, the colour blue is used generally, whereas red is used conventionally to represent oxygenic blood. In the digital illustration, blue and red are still important colours, with symbolic meaning, but in contrast to the hand-drawn sketch other colours are also present. The artery valves are yellow, and the walls of the ventricles and atria are brown. Thus, the digital illustration uses colour to differentiate between different parts of the heart, and reserves black for outlines, neutral representation and writing.

A prominent difference is that of concrete movability. The paper can be moved in the room, placed between the doctor and the couple, lifted, transported and stored. But there is no way to separate the drawn heart from the paper; the paper is always there to bear witness to its production process, getting wrinkled and folded. In order to be shared digitally, the hand-drawn sketch must be scanned or photographed. The digital illustration can be cut out of its original context and seamlessly pasted into a new one.

Conclusions and discussion

Previous research has shown a strong preference among doctors and patients for visual aids for information purposes (Kearns, Citation2019). It has also been shown that most doctors like to draw (Kearns, Citation2019; Kearns et al., Citation2022). Our study confirms this general picture. Among the functions mentioned by Kearns et al., (Citation2022), we have found extensive evidence that drawing is used for explaining the surgery and for supporting informed decision-making. (When it comes to building rapport, however, language seems to be more important). Documentation is also a function, but mainly for the patients. We can also add the function of telling your story to others and raising awareness about heart defects, which were illustrated by the recontextualisations on Instagram. These functions relate to those found in blogging about having a child with a heart defect (Nikolaidou & Bellander Citation2018).

Our detailed, qualitative study of the image used in multiple contexts offers explanations for why drawing is appreciated. For the patients, the hand-drawn image is a condensation of the start of their story: it is a witness not only of the heart defect but also of the visit to the hospital and the meeting with the doctor. During the consultations, drawing helps with structuring the conversation, framing different phases, creating focus, reducing context and slowing down the pace. Tracing these functions back to the material resources of the drawing leads us to see the affordances of the paper (available, foldable, movable, possible to pin up) and the pen (blue and red, a resource for both drawing and writing, a visible focus in the room). Compared to the digital image, the hand-drawn one is tied to its individual situation of origin and tells the story about it.

While earlier research suggested that both patients and doctors prefer images with a higher degree of detail and realism (Scheltema et al., Citation2018, Strong & Erolin, Citation2013), our comparison of the use of hand-drawn to that of digital images may be interpreted as pointing to a different direction. Both doctors and patients appreciate the reduction of the hand-drawn sketch in the consultation room – perhaps for different reasons. Doctors find it important to help reduce less relevant detail and context, and patients want the image to be about their unborn child. All corrections, uneven lines and marks add to the uniqueness. The comparatively more realistic, but also more consistent and clear characteristics of the digital images, however, have their original function in a context where no doctor is available. When recontextualised, they serve the function of informing others about heart defects in general, since the consistency makes the image impersonal and remote from the specific child. Since our data was collected, the information site 1177 has changed its digital illustrations in favour of more naturalistic ones.Footnote1 This is in line with research pointing at the general preference for relative realism. How these images may be recontextualised, and thus how they differ from the previous when it comes to material resources, maybe the subject of future research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

References

- Bellander, T., & Karlsson, A.-M. (2019). Patient participation and learning in medical consultations about congenital heart defects. PLoS One, 14 (7), e0220136. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0220136

- Bellander, T., & Landqvist, M. (2020). Becoming the expert constructing health knowledge in epistemic communities online. Information, Communication & Society, 23(4), 507–522. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2018.1518474

- Dray, S., & Papen, U. (2004). Literacy and health: towards a methodology for investigating patients’ participation in healthcare. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1(3), 311–332. doi:10.1558/japl.2004.1.3.311

- Foucault, M. (1980). Truth and Power. In: Power/knowledge. Selected interviews and other writings 1972–77. Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Kearns, C. (2019). Is drawing a valuable skill in surgical practice? 100 surgeons weigh in. Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine, 42(1), 4–14. doi:10.1080/17453054.2018.1558996

- Kearns, C., Kearns, N., & Paisley, A. M. (2020). The art of consent: visual materials help adult patients make informed choices about surgical care. Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine, 43(2), 76–83. doi:10.1080/17453054.2019.1671168

- Kearns, C., Murton, S., Oldfield, K., Anderson, A., Eathorne, A., Beasley, R., Nacey, J., & Jaye, C. (2022). Estimating the prevalence of drawing in clinical practice among kiwi doctors. Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine, 45 (4), 234–241. doi:10.1080/17453054.2022.2106197

- Kress, G. (2005). Literacy in the new media age. Routledge.

- Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images. The grammar of visual design. Second Edition. Routledge.

- Melander, I. (2019). Multimodal illness narratives : Sharing the experience of endometriosis. Diegesis, 8(2), 68–90.

- Nikolaidou, Z., & Bellander, T. (2018). Health literacy as knowledge construction. Learning about health by expanding objects and crossing boundaries in networked activities. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 4, 1–12.

- Norris, S. (2004). Analyzing multimodal interaction a methodological framework. Routledge.

- O'Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1245–1251. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

- Scheltema, E., Reay, S., & Piper, G. (2018). Visual representation of medical information: the importance of considering the end-user in the design of medical illustrations. Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine, 41(1), 9–17. doi:10.1080/17453054.2018.1405724

- Strong, J., & Erolin, C. (2013). Preference for detail in medical illustrations amongst professionals and laypersons. Journal of Visual Communication in Medicine, 36(1-2), 38–43. doi:10.3109/17453054.2013.790793

- Van Leeuwen, T. (2005). Introducing Social Semiotics. Routledge.