Abstract

Buruli ulcer (BU) is a skin infection caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans and a neglected tropical disease of the skin (skin NTD). Antibiotic treatments are available but, to be effective in the absence of surgery, BU must be detected at its earliest stages (an innocuous-looking lump under the skin) and adherence to prescribed drugs must be high. This study aimed to develop multisensory medical illustrations of BU to support communication with at-risk communities. We used a Think Aloud method to explore community health workers’ (n = 6) experiences of BU with a focus on the role of their five senses, since these non-medical disease experts are familiar with the day-to-day challenges presented by BU. Thematic analysis of the transcripts identified three key themes relating to ‘Detection,’ ‘Help Seeking,’ and ‘Adherence’ with a transcending theme ‘Senses as key facilitators of health care’. New medical illustrations, for which we coin the phrase “5D illustrations” (signifying the contribution of the five senses) were then developed to reflect these themes. The senses therefore facilitated an enriched narrative enabling the production of relevant and useful visuals for health communication. The medical artist community could utilise sensory experiences to create dynamic medical illustrations for use in practice.

Introduction

Buruli ulcer (BU) is one of 20 conditions that are designated by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), and one of the more than 10 that have skin manifestations (now known collectively as the skin NTDs) (Mitjà et al., Citation2017). BU is caused by subcutaneous infection with Mycobacterium ulcerans (Yotsu et al., Citation2018). The first sign of infection is usually a small lump under the skin. Both papules (less than 1 cm in diameter, located within the skin’s dermis layer) and nodules (less than 3 cm in diameter, reaching the skin’s subcutaneous layer) have been described, with nodules being more common in Africa (Yotsu et al., Citation2018). The vast majority of patients with BU present with plaque or ulcer, with or without oedema, which is seen in around 10% of cases (Kumar et al., Citation2022). In plaque forms, the skin is indurated (hardened) becoming slightly elevated, demarcated, and darkened in colour compared to the surrounding skin. It is thought that all papules, nodules, oedemas, and plaque would eventually ulcerate if left untreated; however, in some patients, areas of plaque or oedema can be extensive (Kumar et al., Citation2022). Ulcer formation occurs when the dermis and epidermis of the skin overlying the lesion degenerates, and the surrounding skin and soft tissue collapse to form a deep ulcer with undermined edges. In the most serious cases, ulceration can extend to up to 15% of body surface area. The large open wounds may be susceptible to secondary infection (Kpeli & Yeboah-Manu, Citation2019).

The WHO has defined three categories of lesion (WHO, Citation2012), with category I being a single lesion less than 5 cm in diameter, category II being 5-15cm in diameter (including plaque and oedematous forms), and category III being either a single lesion greater than 15 cm in diameter, multiple lesions or lesions at critical sites (for example head and genitalia). This most serious category also includes cases of patients with bone involvement (osteomyelitis), which are fortunately rare (Kumar et al., Citation2022). All BU lesions require intensive treatment to avoid disability and morbidly, and higher category lesions are more likely to result in permanent bodily deformities or limb amputation, social stigmatisation, discrimination, and the inability to return to a normal productive life (Kumar et al., Citation2022).

BU has been reported in 33 countries worldwide in tropical, subtropical, and temperate climates, particularly in countries of West and Central Africa, and Asia-Pacific (WHO, Citation2012). M. ulcerans is an opportunistic environmental pathogen, which means that BU is not a disease of contagion, rather it is acquired from the environment by a yet unclear mechanism. In Ghana, most of those at risk of BU live in rural areas and are engaged in agricultural activities including subsistence farming (Aboagye et al., Citation2017). A recent study highlighted the public health challenges of providing equitable healthcare to all Ghanaian citizens (Peprah et al., Citation2020). These challenges also affect those with BU and include that most patients travel long distances to access healthcare, poor transportation infrastructure/cost and the continued popularity of traditional healers in preference to modern medicine for cultural and religious reasons (Collinson et al., Citation2020; Peprah et al., Citation2020).

Antibiotic treatments became available in the last 15 years. However, in order for these to be most effective BU must be detected and diagnosed at its earliest stages (papules/nodules, category I and II lesions) and adherence to the prescribed drugs must be high (Nichter, Citation2019). One highly effective control tool has been a programme of trained community health workers (CHWs) and village volunteers, who undertake outreach to reduce fears and increase the early detection of BU (Abass et al., Citation2015; Nichter, Citation2019).

In this work, we wanted to develop medical illustrations that would support this work. Recognising the unique experience of CHWs, we sought their feedback on their perceptions of the disease. In particular, the study focused on the role of the five senses (sight, smell, sensation/touch, hearing and taste) as a means to develop an enhanced set of multisensory medical illustrations that could be used alongside conventional approaches. To achieve this, we undertook a two-stage process to:

Use a Think Aloud methodology to explore how the senses influence CHWs’ management of patients with BU.

Develop a set of enhanced multisensory medical illustrations based on the findings.

Stage 1: the Think Aloud study

Method

Study Site

The rationale for choosing Ghana is because this part of the African continent endures a high number of cases of both BU and yaws, and which are co-endemic in this region (Okine et al., Citation2020). It is the location of collaborator Professor Richard Phillips from the Kumasi Centre of Collaborative Research in Tropical Medicine (KCCR), an international platform for biomedical research, whose work is associated with the KNUST School of Medical Sciences (SMS), Ghana, and the Bernhard-Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine (BNITM), Hamburg, Germany. It is through this collaboration with the KCCR that the CHW participants were organised.

Study design

A qualitative Think Aloud method was used to encourage participants to speak freely with minimal input from the researcher (Cotton & Gresty, Citation2006; Ericsson & Simon, Citation1980; van Oort et al., Citation2011). This approach has been used across a number of domains including drug use, body image and eating behaviour (McLeod & Ogden, Citation2013; Ogden & Roy-Stanley, Citation2020; Ogden & Russell, Citation2012).

Participants

There were 6 participants (), all of whom are CHWs in the Ashanti region of Ghana, which is endemic for BU. They work with coordinated Buruli ulcer clinics in Agogo Presbyterian Hospital, Dunkwa Government Hospital, and Tepa Government Hospital in Ashanti or Central regions in Ghana. All had considerable experience working with BU (>10 years).

Table 1. Participant demographic information

Procedure

This study received a favourable ethical opinion from the University of Surrey Ethics committee (FHMS-21-22 134 EGA). Following written consent, the Think Aloud sessions took place using Zoom. These were audio recorded and transcribed using Zoom functionality. The transcripts were cross-checked verbatim against the audio recordings.

The Think Aloud process

Participants were presented with a single slide on the screen illustrating the five senses (). They were then given the following instructions ‘Health care workers such as yourself may interact with Buruli ulcer patients using your senses, which are vision, hearing, smell, taste, sensation, or touch. The purpose of this session is to gather as many of these sensory experiences as possible’. They were left alone for 7 minutes ‘to recall any experiences’ and reminded not to use anyone’s names and that ‘there are no right or wrong answers’.

Data analysis

Transcripts were analysed inductively using thematic analysis following the guidelines by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) in five stages. The transcripts were read repeatedly to familiarise the researchers with the content with each transcript coded regarding pertinent information relating to the participants’ sensory experiences. Relevant sections were highlighted and refined until patterns that were representative of the data were revealed. Reviewing and refining the themes was carried out to ensure there was enough supporting evidence to present a clear narrative. Extracts that were perceived to be important and relevant were then coded and these codes were then clustered together and transformed into more analytical and higher-level sub-themes, which were grouped into themes and an overall thematic map. To establish a degree of inter-rater reliability and credibility, the coding process was discussed within the research group throughout. Exemplar quotes thereafter identified for each sub theme.

Results

Data analysis described three primary themes: ‘Detection,’ ‘Adherence,’ ‘Help seeking,’ with an overall theme of ‘Senses as Facilitators.’

Theme 1: Detection

The CHWs gave in-depth descriptions of each presentation type of BU, according to sensory information derived from i) patients’ common experiences whilst living with BU, and ii) their own experiences. They gave equal weight to each of the presentations of BU (papule/nodule, plaque, oedema, small and large ulcers, with and without osteomyelitis) irrespective of the frequency that they occur, as described above.

Patient experiences

CHWs described patients’ experiences at different stages/presentations of BU disease; with early stages (nodules/papules) of BU having little impact, compared to more serious presentations causing more concern. In particular, most CHWs emphasised the strong and unpleasant smell associated with ulcerated BU lesions that stigmatised the patients and sometimes put them off their food, linking this smell to disturbance of taste.

‘However, [for] the sense of smell, unless the ulcer or sometimes the osteo [myelitis], they are ok, but for the ulcer it kind of comes with smell that is very uncomfortable. In fact, if a Buruli ulcer wound was in this room you would realise that the smell in that part of the environment looks different’ (participant 5).

‘And with the osteo myelitis form too this causes so much pain because in this case on vision you can see bone exposed and also smells, it has a very bad odour’ (participant 4).

‘And when people with typical Buruli ulcer lesions get closer to people who don’t have the disease, sometimes you see them try to move away from them, especially when they come to the consulting room…you see people squeezing their face because of the smell’ (participant 1).

‘… then the taste is related to the smell. Because sometimes the environment determines how the person feels and then… that will affect your sense of taste as well. So, most of them usually feel like if it’s about feeding, they are not hungry because they don’t like the smell’ (participant 5).

For most presentations of BU (papule/nodule, plaque, oedema, and ulcers), in line with expectations, participants described how patients seemed to feel no pain accompanying the infection, even when it was palpated or samples are taken for diagnosis by inserting swabs under the undermined edge of the ulcer:

‘All the lesions if we look at the clinical forms, the patients you touch will tell you it’s very painless, they don’t feel any pain’ (participant 1).

‘They will tell you that I don’t feel any pain if you palpate, even if you swab the undermined edges, they will you that they don’t feel any pain’ (participant 3).

‘And with the Osteomyelitis form too this causes so much pain because in this case on vision you can see bone exposed and also smells, it has a very bad odour. And the sensation and touch the patients are in a very good pain. A very good amount of pain and they complain because of the result of the exposed bone’ (participant 4).

‘But with secondary infection, they will tell you that the lesion when you palpate, they will feel pain, depending in the degree of the infection’ (participant 3).

‘For instance, when you consider the plaque, the plaque feels kind of hard, rough in nature. Touching it, the sensation is kind of painless. And then the patients, not had anyone complain of excessive pain. However, there is discomfort and then the feeling of, not usual, of the plaque being formed on the skin is what worries them’ (participant 5).

In summary, in the early stages of BU, the patients’ sensory experiences are fairly minimal compared to the later stages. This highlights the importance of early detection to minimise the chance that the patient will experience pain or other stigmatising factors such as the smell.

Community health worker experiences

Several of the CHWs described the process by which they carried out detection of BU using their senses when patients had different presentations of BU. Whilst it was still a small lump (papule or nodule) under the skin in an otherwise healthy person, this involved both the senses of sight and touch. This allowed them to actively seek for external signs before checking any changes to determine if they were concerning. Sight was therefore a key sense for appraisal of apparently healthy people because the papule and nodule stages are not easy to detect:

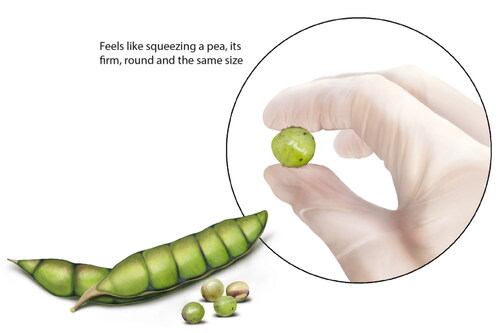

‘Let’s say if I see a nodule, I know it has a very well-defined margin, and looking at the nodule, it’s round and looks like a boil’ (participant 4).

‘it feels directly attached to the skin and the patient doesn’t complain of any pain’ (participant 4).

The process for detecting the plaque presentation of BU also involved both sight and touch. By sight, plaque was described as displaying discolouration on the skin, and having a visible boundary between unhealthy and healthy skin. The sense of touch was also used to detect the typical induration of the skin:

‘The plaque feels kind of hard, rough in nature’ (participant 5).

‘It doesn’t feel too warm to touch but that site is very indurated, so it feels very hardened to the touch’ (participant 4).

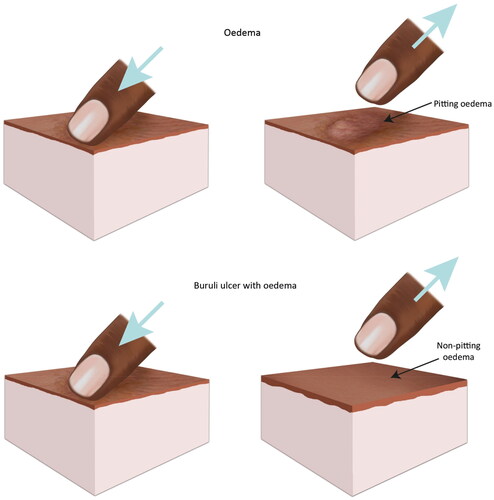

‘Looking at oedema, it could affect any part of the body… but usually we see… that whole portion of the arm, the upper limb or the lower limb could be very hardened and indurated and it is non pitting…. The oedema it is non pitting compared to other oedemas, like cellulitis, and other forms of oedemas that we will see in pregnant women’ (participant 4).

‘For example, for people who are seeing it for the first time, we see we have newly posted health workers coming into the clinic, on internships and all of those, and when they see it for first time, their reaction tells you this is not what they anticipated, what they had really heard about…. For our new interns, who get to see it for the first time some of them have issues and even complain they have not been able to eat well and even skipping meals…’ (participant 6).

‘It is unpleasant to see the big lesions like the ulcers…affecting the face or the genitalia…. when I started working with Buruli ulcer patients’ (participant 6).

The smell of BU was particularly associated with this presentation, and most described the effect it has on them or their colleagues working in clinics or in the field. The smell was described as ‘offensive’, ‘not good’, a ‘very bad odour’, ‘uncomfortable to be with’. One participant also described how they have never got used to the smell of BU. This sometimes meant that they had to try hard not to have a negative reaction in front of patients which could have caused offence and been stigmatising.

‘And even for those of us who have worked with patients over the years and encountered these smells over the years, but it doesn’t change actually, it still smells bad even, no matter how long you have been working with them’ (participant 6).

Several of the CHWs linked their experience of BU to taste, exclusively about the advanced (ulcerated and osteomyelitis) presentations. Two described how they would experience increased salivation in the mouth, requiring them to go to the washroom to wash it out:

‘Because of the offensive nature of the wound, you can have some increased salivations in your mouth. You may have to go to the washroom and get the saliva out of your mouth (participant 4).

‘You get some saliva coming into your mouth and you feel like BU is bad and also… tasting it, you have to picture it, you have to think about how it looks like because you see the necrotic slough on the surface so tasting will become bad, you might not be able to enjoy your food after seeing it for the time, these bad wounds’ (participant 6).

Theme 2: Help seeking

The CHWs also frequently described aspects relating to help seeking behaviour of patients with BU and this second theme reflects the factors that may cause delays in their seeking help from medical practitioners involving two sub-themes i) aversion and ii) lack of opportunity.

Aversion

It was clear from the transcripts that BU lesions induced aversion amongst both patients and the general public. There was strong evidence of patients with BU being stigmatised, particularly due to the smell and fear of strong reactions that the smell can induce in the general public as well as within their own communities or even families.

‘When they come to consulting room… you see people squeezing their face because of the smell. And this one also lead to stigma and sometimes even discrimination’ (participant 1).

‘It has a very bad smell and sometimes such patients are even left neglected because of the kind of smell emanating from the lesion’ (participant 4).

‘When they have to travel to the health facility for their community, the vehicles in which they transport themselves, they have people not being pleasant sitting in the same vehicle with such patients… And even when they have got into the hospital at the main room where you have other patients… you see people covering their nose with handkerchiefs or tissues or stuff because of the bad smell that come from the lesions… the general public people will stigmatise with the smell and all those people will not want to come close’ (participant 6).

One CHW also described how the appearance of the lesion scared patients, especially in more severe cases:

‘The moment they see their lesion with their eyes, some of them they don’t want to have a look, they say it is very scary, very scary. More especially the bigger lesion’ (participant 1).

‘When you have to show videos on BU in the communities… you realise that a lot of people tend to turn their eyes from the videos, they tend to close their eyes or turn their head away from the lesions’ (participant 6).

Help seeking seemed also to be delayed due to the absence of pain, and this lack of aversion could be seen as one factor that contributes to delays since the infection doesn’t interfere with their daily lives. This is particularly true of the earliest signs of infection; a papule or nodule, which looks and feels harmless to them:

‘About the papule, the person feels that there is a small kind of boil that has been noticed on the skin… the person is not able to explain how it feels like; so, the papule is painless’ (participant 5).

‘And looking at the nodule, it’s round and looks like a boil…. you touch the nodule… and the patient doesn’t complain of any pain’ (participant 4).

‘The nodule… is painless…. Then a person notices that there has been a raised portion of that particular area. However, it’s still painless then the person does not actually feel that it’s of concern to him or her’ (participant 5).

‘But when it’s a nodule, a papule or plaque even if it’s or oedematous, its less painful, like we know Buruli ulcer its painless unless it’s ulcerating with other infections’ (participant 6).

‘When it comes to another form, osteo involvement… most [patients] usually complain of pain in their bone’ (participant 5).

‘There is also limitation of movement at times, and this is related to the osteo, or bone involvement… It also kind of deforms [the patient]; and you can see their gait is also affected, [and [movement is kind of challenged because of the related pain that area’ (participant 5).

‘Then the osteo, sometimes looking rough, sometimes the persons movement will tell you that this person is actually in pain… you realise that… they are in pain even though we say that initially its painless’ (participant 6).

Lack of opportunity

CHWs also described how a lack of opportunity influenced the patients’ help seeking behaviour. It is known that BU endemic communities struggle with factors such as the need to use public transport for long distances due to the centralisation of healthcare facilities (Collinson et al., Citation2020). This is thought to be one of the reasons why patients delay seeking help from medical practitioners and instead consult traditional healers. Traditional approaches often include wrapping the lesions in herbal preparations before their lesion had got to the ulcerative stage:

‘Because over here some people tend to apply herbs in the early stages, when they don’t know what its is’ (participant 6).

‘After 8 weeks intensive drug treatment, they have to visit the facility first to review the lesion. Every month. Until the lesion is healed’ (participant 2).

‘So, after they have healed, and no physio done for them, end up getting contractures. You have to do prevention disability physiotherapy for the clients’ (participant 2).

Theme 3: Adherence

The third theme related to patient adherence to treatments and the barriers and facilitators that influenced whether or not patients followed medical advice. This was reflected in two sub-themes: i) anticipated harm and ii) actual side effects.

Anticipated harm

Some of the descriptions of the sensory experiences of CHWs working with patients with BU spoke to issues that could be ascribed to anticipated harms associated with treatment at the clinics. Under this umbrella comes the known preference for many patients with BU to first visit traditional healers who live in the local communities, who apply herbal concoctions to the lesions having impacts related to smell:

‘Because [in Ghana] some people tend to apply herbs in the early stages, when they don’t know what it is. so, the herbs make it smell… even sometimes putting on bandages for days, without opening it, and then when it ulcerates you see the smell coming so bad’ (participant 6).

‘With the sense of touch, you realise that some patient without secondary infection they will tell you that they don’t feel any pain when you palpate. But with secondary infection, they will tell you that the lesion when you palpate, they will feel pain, depending in the degree of the infection’ (participant 3).

‘So that makes wound dressing a bit difficult, because you have to use materials which are forceps, which are gauze, using your normal saline, but the mere sight of patients seeing you going to the wound makes them feel bad, and you… also feel pity for the patients knowing the pain and discomfort they have to go through with respect to the touch aspect of their wounds’ (participant 6).

Side effects

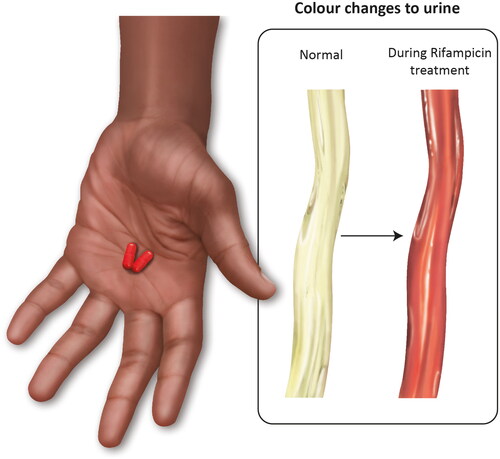

CHW also described the role of side effects in patients’ adherence to antibiotic treatment. For example, rifampicin stains the urine red which can be worrying for patients making them reluctant to continue to take it.

‘And ‘vision’, it’s about what they see when they urinate after taking the antibiotics. Some of them complain they have seen a change of their urine. Very red like blood’ (participant 1).

They therefore always tried to manage patients’ expectations before they took the drug:

‘When they take rifampicin, you realise that their urine colour changes to red. So sometimes they feel very nervous. So, if you don’t explain to them before they are taking the drug, they sometimes feel very nervous when they come across some of these things. Like the urine colour changing to red’ (participant 3).

‘And taste, they complain of the scent of the drug, especially rifampicin’ (participant 1).

‘And with that of taste… some also had challenging with the drug… they said that the drug taste bitter. So, had very, difficulty sometimes taking the drugs. Also, with that of the smell, they say that the drugs, the scent or the smell… from the drug also make it very, difficult to also take the drug’ (participant 3).

Streptomycin, which requires daily intramuscular injection and has known potential serious side effects (including irreversible deafness) is no longer used widely (Kumar et al., Citation2022). The WHO now recommends the all-oral combination of rifampicin and clarithromycin to avoid these issues (WHO, Citation2012). However, these known side effects were noted by some CHWs.

Transcending theme: the senses as key facilitators to health care

The role of the five senses can be seen to permeate all participant’s accounts and played a key role in how they interact with their patients. For example, sight was seen as key to how CHWs identified all presentations of BU. It could make patients frightened to look at their own lesion and could deter a patient from taking medication as it changed the colour of their urine. Touch was key to detection to determine if a lump under the skin moved (and was therefore likely to be BU) and whether the skin in oedema remained pitted (and was therefore unlikely to be BU). Similarly, the sensations felt by patients were important because the absence of pain in the early stages could reduce help seeking behaviour, whilst the presence of pain could be a trigger to come forward for treatment. The anticipation of treatment-related pain from the dressing of larger lesions could discourage patients from continuing with treatment. The characteristic smell of ulcerated lesions was important for detection, help seeking and adherence, but mostly in a negative way, causing stigmatisation. The smell of medication could also put patients off taking it. Taste also had a role to play, mainly related to treatment adherence as the antibiotics have a bitter and unpleasant taste. While hearing was important historically as hearing loss could be a side effect of the use of medication, this was not given great weight by the CHW unless the BU lesions were at sites directly impacting the auditory system.

Stage 2: Developing the multisensory medical illustrations

Method

Choosing the focus for the illustrations

The next stage of the process involved identifying ways to add sensory experiences under the three themes above into medical illustrations; we term these “5D illustrations”, to indicate how they incorporate the five senses into improved healthcare communication. To this end, these sense-based phrases were cross referenced with existing information and illustrations on BU, to identify which theme-based quotes would be of most benefit in the clinical domain. These were as follows: Detection: ‘And as well the oedema it is non pitting compared to other oedemas, like cellulitis, and other forms of oedemas that we will see in pregnant women’ and ‘it feels directly attached to the skin and the patient doesn’t complain of any pain’; Help Seeking: ‘the person feels that there is a small kind of boil… the papule is painless’ Adherence: ‘When they take Rifampicin, you realise that their urine colour changes to red. So, sometimes they feel very nervous’ and ‘The drug tastes bitter. So had, very, difficulty sometimes taking the drugs’. In line with these, five medical illustrations were produced.

Producing the illustrations

To start, additional reference photographs were gathered, such as the antibiotics rifampicin and clarithromycin, water streaming from a tap, and of people in West Africa to show their clothing, smiling faces and elements such as hands holding glasses of water. Next, the phrases were developed into initial drawn ideas and concepts using sketching with pencil on paper (see examples in and ).

Figure 2. Illustration of the antibiotic tablets prescribed for BU treatment. The yellow tablet is clarithromycin and the red capsule as rifampicin; only the rifampicin colours urine red. Illustration by Joanna Butler.

Figure 3. Initial sketching. One of a series of pencil sketches used to formulate ideas. Illustration by Joanna Butler.

Next, the best sketches were assembled into fewer and more detailed versions until a single version was ready for colour rendering using Adobe® Photoshop (24.1.1 version, 2023). The final pencil versions were scanned and saved as jpeg files. Each was placed onto an A4 sized canvas and individually rendered into colour versions, using the Pencil and Brush tools with a pre-determined palette of colours. Artistic rendering used a drawing tablet (Wacom Intuos Pro) connected to an iMac with a 27” display screen (a MacOS version 12.5) and the use of a handheld Intuos Wacom Stylus.

Levels of examination

During the process, a level of examination and self-questioning was carried out to ensure there was sound reasoning for the content within each illustration. All authors, including clinicians with expertise in dermatology and BU, took part in the feedback process. Moreover, cultural input, such as the typical dress and appearance of patients with BU (who are mostly school-age children), was obtained from Ghanaian nationals. For example, this resulted in the short hair style and a generic tunic similar to those worn by all Ghanaian girls whilst attending secondary school. For the remaining content, realistic fluid was created by referring to the water streaming from a tap photographic reference’ and before ‘for the representation of urine, and a dark red during rifampicin treatment. The skin sections were paired down versions of the anatomy of skin layers, with an imprint (pit) left by a finger pressing onto the skin surface and what it would have looked like once lifted off.

The parameters with which to produce the illustrations needed to comply with self-imposed boundaries to work within printed documents (portrait A4), to include only the subtle use of labelling, or without any labels, if possible, and to have a level of realism and suitability for the target audience that matched the first clinically approved medical illustrations of BU we previously published. A colour palette was selected to accurately reflect West African tradition, social values, cultural identify, and climate (Dickinson, Citation2011; Best, Citation2017). The limited resources in Ghana were also a consideration. The illustrations were required to work as black and white versions, especially when photocopiers are used to create multiple print versions. To print in black and white as effectively as possible, the illustration colours were not too dark, or dark areas kept to a minimum and used next to lighter colours to hep distinguish area of tissue, to avoid merging, to retain clarity by using areas of white space either around or in between individual graphics.

Results

Five new medical illustrations for the key components of ‘Detection,’ ‘Help Seeking’ and ‘Adherence’ reflecting four different senses (sight, touch, smell, taste) are shown in . Hearing was not completed as it was not key to the CHWs experiences.

Figure 4. Detection: ‘And as well the oedema it is non pitting compared to other oedemas, like cellulitis, and other forms of oedemas that we will see in pregnant women’. This figure represents paired down skin anatomy with a finger pressing on and off the skin in search for oedema due to poor circulation, likely to either react to pressure leaving either a pit, or not, due to the variations between pitting and non- pitting oedema. This reflects the sense of touch. Illustration by Joanna Butler.

Figure 5. Detection: ‘Feels directly attached to the skin and the patient does not complain about pain’. For the purpose of explanation, the illustration encompasses a visual clue analogy of a pea to bring about viewer engagement and to exemplify the need for palpation during detection of BU lumps under the skin. The pea was chosen to be representative of a local variety grown within Ghana, called the Pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan). This reflects the senses of touch/sensation and sight. Illustration by Joanna Butler.

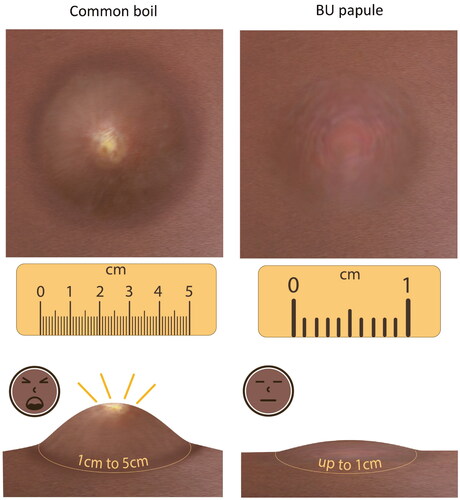

Figure 6. Help seeking: ‘the person feels that there is a small kind of boil… the papule is painless’. This figure represents a papule within the skin and comparing it to a boil. The points are a papule is smaller and painless, whereby a boil may look similar, but it is painful, and larger and develops a yellow pus. This reflects the senses of sight and touch. Illustration by Joanna Butler.

Figure 7. Adherence: ‘But the problem has to do with rifampicin, when they take rifampicin, you realise their urine colour changes to red. So, sometimes they feel very nervous.’ This figure represents an open hand holding two capsules as a friendly gesture. Alongside it are examples of urine colour. One is normal, the other red, designed to make the patient aware of such a change. Knowledge is empowerment for the patient. This reflects the sense of sight. Illustration by Joanna Butler.

Figure 8. Adherence ‘The drug tastes bitter. So had, very, difficulty sometimes taking the drugs’. This figure represents a girl of school age about to take the antibiotic medication rifampicin for BU treatment. The confident smiling attitude designed to bring about a demeanour that implies the drug is not harmful, despite its bitter qualities. This reflects the senses of taste and smell. Illustration by Joanna Butler.

Discussion

The role of trained CHWs in outreach programmes that aim to increase the detection of BU has been proven in a variety of settings in countries of West Africa, including Ghana where the participants in our study were from (WHO, Citation2021). Currently the training tools used to train the CHW, and that they then use in educational outreach visits, use entirely photographic material (WHO, Citation2018, Citation2014). During this work, we developed the concept that medical illustration goes beyond what photographs can achieve by building in sensory experiences.

We approached this using a Think Aloud method as a method that could not be influenced by our own conscious and unconscious bias about what senses we were expecting to be important, and how. Our findings provide support for previous research using the same approach to encourage participants to speak freely (Cotton & Gresty, Citation2006; Ogden & Roy-Stanley, Citation2020; van Oort et al., Citation2011). Indeed, while some of the narrative of the transcripts speaks to elements that are well versed in the literature, such as BU being a disease with a surprising lack of pain considering the serious infections present, there were highly illuminating observations in areas that we did not anticipate.

Thematic analysis of the transcripts of the six participants identified three key themes relating to detection, help seeking and adherence. In detection, the description of the sight and touch of the different presentations was in line with expectations, however we had not anticipated such a strong and unanimous description of the smell of BU ulcerative lesions, especially those with osteomyelitis. While we chose not to illustrate this, it is an area that warrants further research. Interestingly, the “characteristic smell” (described as a “strong smell, like the smell of rotten fish, cassava or cheese, mixed with smell of pyocyanic bacteria”) gained 3 points in Buruli Score (Mueller et al., Citation2016), being the element with the most predictive power for BU positivity by PCR. Smell has previously been noted as one of the main stigmatising factors for BU (Muela Ribera et al., Citation2009), but is not widely discussed. Here, the smell is likely to be worse if there is a secondary infection (Mueller et al., Citation2016). The negative experiences associated with the more serious infections strongly supported the need for better resources that could help those in endemic communities spot non-ulcerated infections therefore we developed an illustration that shows how BU oedema differs from diabetic oedema () and another that shows the pea-like and mobile nature of the nodule ().

For help seeking, this described how aversion to BU lesions contributed to behaviours, which was compounded by a lack of opportunity. There has been much research on the factors that influence patients with BU help seeking behaviour, in the cultural context of the communities in which the disease is endemic (Nichter, Citation2019). It is important to recognise that some of these are marginalised communities, including rural subsistence farmers in areas distant from where healthcare is concentrated. Further, many patients with BU are children in their early teens, and they are not making their own healthcare decisions (Agbo et al., Citation2019), hence cases of BU impact entire family dynamics (Agbo et al., Citation2019). Here we developed an illustration that would promote help seeking by differentiating papules from common boils ().

For adherence, these encompassed both anticipated harms and actual side effects. Adherence rates to BU antibiotic regimens have been reported to be as high as 94% when patients are well-supported and closely monitored (Phillips et al., Citation2014). However, others have found much lower adherence rates of ∼50%. After locating non-compliers, reasons given for not continuing with the treatment included travel costs, that ulcers were healed quicker than the treatment course, and the ototoxicity of streptomycin (Klis et al., Citation2014). It’s interesting that the Ghanaian study used urine colour change as evidence of treatment compliance for rifampicin (Phillips et al., Citation2014), whereas our Think Aloud study revealed that this is also of concern to patients with BU that may influence adherence. We decided to illustrate both this physiological and harmless change (), as well as producing a positive image of a young woman taking her antibiotic medication in her school wear to overcome potential issues of the medication tasing bitter ().

Transcending these themes was the notion of ‘Senses as key facilitators to health care’ which highlighted how the five senses played a key role across all themes. Our results illustrate the power of a non-biased research process to discover previously hidden detail from non-medical, but expert and highly experienced, CHWs that is illuminating with regard to disease detection and management. Hence, medical illustrations that focus only on sight are omitting the complexity of ways in which healthcare professionals engage with their patients, irrespective of the disease or context.

In summary, this inductive qualitative process using a Think Aloud method indicates that the sensory experiences of CHWs working in Ghana with BU can be incorporated into medical illustrations (for which we coin the phrase “5D illustrations”). This could facilitate their practice in the field when supporting patients through the stages of help seeking, detection and patient adherence. Our intention now is to gain further feedback from our original CHWs and additional local experts together with patients to explore the use of these illustrations in practice and to produce a health education resource.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abass, K. M., van der Werf, T. S., Phillips, R. O., Sarfo, F. S., Abotsi, J., Mireku, S. O., Thompson, W. N., Asiedu, K., Stienstra, Y., & Klis, S. A. (2015). Buruli ulcer control in a highly endemic district in Ghana: role of community-based surveillance volunteers. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 92(1), 115–117. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.14-0405

- Aboagye, S. Y., Asare, P., Otchere, I. D., Koka, E., Mensah, G. E., Yirenya-Tawiah, D., & Yeboah-Manu, D. (2017). Environmental and behavioral drivers of Buruli ulcer disease in selected communities along the densu river Basin of Ghana: A case-control study. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 96(5), 1076–1083. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.16-0749

- Agbo, I. E., Johnson, R. C., Sopoh, G. E., & Nichter, M. (2019). The gendered impact of Buruli ulcer on the household production of health and social support networks: Why decentralization favors women. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 13(4), e0007317. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007317

- Best, J. (Ed.). (2017). Colour design: theories and applications. https://books.google.co.uk/books/about/Colour_Design.html?id=GfqpDQAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Collinson, S., Frimpong, V. N. B., Agbavor, B., Montgomery, B., Oppong, M., Frimpong, M., Amoako, Y. A., Marks, M., & Phillips, R. O. (2020). Barriers to Buruli ulcer treatment completion in the Ashanti and Central Regions, Ghana. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 14(5), e0008369. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008369

- Cotton, D., & Gresty, K. (2006). Reflecting on the think-aloud method for evaluating e-learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 37(1), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2005.00521.x

- Dickinson, K. (2011). 8 - The use of colour in textile design. In A. Briggs-Goode, & K. Townsend (Eds.), Textile design (pp. 171–191e). Woodhead Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1533/9780857092564.2.171

- Ericsson, K. A., & Simon, H. A. (1980). Verbal reports as data. Psychological Review, 87(3), 215–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.87.3.215

- Klis, S., Kingma, R., Tuah, W., Stienstra, Y., & van der Werf, T. S. (2014). Compliance with antimicrobial therapy for buruli ulcer. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 58(10), 6340–6340. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.03763-14

- Kpeli, G. S., & Yeboah-Manu, D. (2019). Secondary infection of Buruli ulcer lesions. In G. Pluschke & K. Röltgen (Eds.), Buruli ulcer: Mycobacterium ulcerans disease (pp. 227–239). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11114-4_13

- Kumar, A., Preston, N., & Phillips, R. (2022). Picturing health: Buruli ulcer in Ghana. Lancet (London, England), 399(10327), 786–797. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00157-X

- McLeod, A., & Ogden, J. (2013). Thinking-aloud about stereotypical mainstream and opiate-dependent lifestyle images: A qualitative study with opiate addicts. SAGE Open, 3(3), 215824401350115. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013501156

- Mitjà, O., Marks, M., Bertran, L., Kollie, K., Argaw, D., Fahal, A. H., Fitzpatrick, C., Fuller, L. C., Garcia Izquierdo, B., Hay, R., Ishii, N., Johnson, C., Lazarus, J. V., Meka, A., Murdoch, M., Ohene, S.-A., Small, P., Steer, A., Tabah, E. N., … Asiedu, K. (2017). Integrated control and management of neglected tropical skin diseases. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 11(1), e0005136. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005136

- Muela Ribera, J., Peeters Grietens, K., Toomer, E., & Hausmann-Muela, S. (2009). A word of caution against the stigma trend in neglected tropical disease research and control. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 3(10), e445. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000445

- Mueller, Y. K., Bastard, M., Nkemenang, P., Comte, E., Ehounou, G., Eyangoh, S., Rusch, B., Tabah, E. N., Trellu, L. T., & Etard, J. F. (2016). The "Buruli Score": Development of a multivariable prediction model for diagnosis of mycobacterium ulcerans infection in individuals with ulcerative skin lesions, Akonolinga, Cameroon. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 10(4), e0004593. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004593

- Nichter, M. (2019). Social science contributions to BU focused health service research in West-Africa. In G. Pluschke & K. Röltgen (Eds.), Buruli ulcer: Mycobacterium ulcerans disease (pp. 249–272). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11114-4_15

- Ogden, J., & Roy-Stanley, C. (2020). How do children make food choices? Using a think-aloud method to explore the role of internal and external factors on eating behaviour. Appetite, 147, 104551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.104551

- Ogden, J., & Russell, S. (2012). How Black women make sense of ‘White’ and ‘Black’ fashion magazines: A qualitative think aloud study. Journal of Health Psychology, 18(12), 1588–1600. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105312465917

- Okine, R. N. A., Sarfo, B., Adanu, R. M., Kwakye-Maclean, C., & Osei, F. A. (2020). Factors associated with cutaneous ulcers among children in two yaws-endemic districts in Ghana. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 9(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-020-00641-2

- Peprah, P., Budu, H. I., Agyemang-Duah, W., Abalo, E. M., & Gyimah, A. A. (2020). Why does inaccessibility widely exist in healthcare in Ghana? Understanding the reasons from past to present. Journal of Public Health, 28(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-019-01019-x

- Phillips, R. O., Sarfo, F. S., Abass, M. K., Frimpong, M., Ampadu, E., Forson, M., Amoako, Y. A., Thompson, W., Asiedu, K., & Wansbrough-Jones, M. (2014). Reply to "compliance with antimicrobial therapy for buruli ulcer. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 58(10), 6341–6341. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.03874-14

- van Oort, L., Schröder, C., & French, D. P. (2011). What do people think about when they answer the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire? A ‘think-aloud’ study. British Journal of Health Psychology, 16(Pt 2), 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910710X500819

- WHO. (2012). Treatment of Mycobacterium ulcerans disease (Buruli ulcer); guidance for health workers. Wold Health Organisation. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/77771/1/9789241503402_eng.pdf?ua=1

- World Health Organization. (2014). Laboratory of diagnosis of Buruli ulcer: A manual for health care providers. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241505703

- World Health Organization. (2018). Recognizing neglected tropical diseases through changes to the skin: A training guide for front line health workers. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241513531

- World Health Organization. (2021). Health Workforce (HWF) (2021). What do we know about community health workers? A systematic review of existing reviews. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/what-do-we-know-about-community-health-workers-a-systematic-review-of-existing-reviews

- Yotsu, R. R., Suzuki, K., Simmonds, R. E., Bedimo, R., Ablordey, A., Yeboah-Manu, D., Phillips, R., & Asiedu, K. (2018). Buruli ulcer: a review of the current knowledge. Current Tropical Medicine Reports, 5(4), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40475-018-0166-2