Abstract

Background Nonoperative treatment is preferred for clavicular fractures irrespective of fracture and patient characteristics. However, recent studies indicate that long term results are not as favourable as previously considered.

Methods We have identified predictive risk factors associated with demographic and baseline data on clavicular fractures. In particular, the following symptoms were investigated: pain at rest, pain during activity, cosmetic defects, reduction in strength, paresthesia and nonunion until 6 months after injury. We followed 222 patients with a radiographically verified fracture of the clavicle, and who were at least 15 years of age, for 6 months.

Results Nonunion occurred in 15 patients (7%). 93 patients (42%) still had sequelae at 6 months. Displacement of more than one bone width was the strongest radiographic risk factor for symptoms and sequelae. Both radiographic projections used in this study (0° and 45° tilted view) provided important information. A comminute fracture and higher age were associated with an increased risk of symptoms remaining at 6 months. Shortening was not predictive of functional outcome; nor was the site of the fracture in the clavicle.

Interpretation The risk for persistent symptoms following nonoperative treatment of clavicular fractures was far higher than expected. Based on these findings it seems reasonable to explore the possibly use of alternative treatment options including surgery for certain clavicular fracture types.

When this study was initiated, nonoperative treatment was the rule—irrespective of the type of clavicular fracture (Rowe Citation1968, Paffen and Jansen Citation1978, Kohaus and Sasse Citation1980, Schmit-Neuerburg and Weiss Citation1982, Langenberg von Citation1987, Stanley and Norris Citation1988). Only a few reports, mostly retrospective and involving a small number of patients, have described the occurrence of complications such as shortening, deformity, nonunion, neuro-vascular affection and different subjective disabilities (Ali Khan and Lucas Citation1978, Effenberger Citation1981, Zenni Jr et al. Citation1981, Echtermeyer et al. Citation1984, Eskola et al. Citation1986, Jupiter and Leffert Citation1987). In a recent publication, we reported on the etiology and epidemiological aspects of a defined subgroup from the present prospective patient series (Nowak et al. Citation2000). The objective of the present study was to describe the natural history and to identify risk factors associated with the outcome of clavicular fractures.

Patients and methods

During a 3-year period (1988–1991), 245 patients ≥ 15 years of age and living in the county of Uppsala, Sweden, with a radiographically verified fracture of the clavicle were included consecutively in a prospective study. At the time of fracture of the clavicle, the patients answered questions from a specific questionnaire. This was followed by an interview by JN, to clarify different aspects of and details relating to the fracture. Additional clinical and radiographic examination was done according to a strict protocol. Patients were examined 1, 2, 3 and 6 months after the fracture. The standardized radiographic examination was done after 1 week and at 6 months.

Radiographic variables

We used anteroposterior 0° and 45° tilted radiographic views to describe different characteristics of the fractures. 3 different fracture locations were identified: the acromial, middle and sternal part. A point just medial to the conoid tuberosity was defined as the dividing line between the acromial part of the clavicle and the middle part. The sternal part of the clavicle was defined as the part located medial to the lateral border of the first rib. The fracture was classified according to the site of the main part of the fracture (Nowak et al. Citation2000).

On each radiograph, the cortices were evaluated for the amount of bridging. Healing was defined as the disappearance of the cortical interruption at the fracture site as a result of callus formation. If the fracture had not healed within 6 months, it was classified as a nonunion. The type of fracture was determined and the degree of displacement was measured, both in mm and in relation to the bone width of the clavicle. Shortening was defined as being positive if the main fragments overlapped by more than 5 mm in one or both projections.

Definition of the baseline and endpoint variables

The baseline data were: age, sex, smoking, fractured side and dominant side, fracture location, fracture type (angulation, transverse, oblique, comminute with or without transversally placed fragments), shortening, displacement between the main fragments of the clavicle, and bony contact between the main fragments of the clavicle and the fragments at the fracture site. The endpoint sequelae were defined by the patient’s answer to “Are you fully recovered from your clavicular injury?” (yes/no), and the answer to the question “If so, after how many weeks?” constituted recovery time. Other endpoints (pain at rest, pain during activity, strength reduction and cosmetic defects) were based on answers recorded on a VAS scale (0–10). These variables were also used after dichotomization (e.g. pain at rest = no/yes).

Statistics

The association between demographic and base-line variables and the outcome of different end-points at 6 months after injury was explored using chi-square tests (dichotomous data), Wilcoxon rank sum tests (ordinal data) or t-tests (the variable age). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Selected subgroups of patients were compared at 6 months using estimated relative risks with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Patient characteristics at baseline ()

The mean age was 31 (15–67) years and one-third of the patients were women. Most of the fractures (71%) were situated in the middle part of the clavicle. Comminute (41%) and spiral/oblique (38%) fracture types were most common, while transverse fractures occurred in 21% of all patients. Comminute fractures with transversally placed fragments seemed to be associated with cosmetic defects, while both angulation of the fracture and shortening showed no such association.

Table 1. The demographic and baseline characteristics of the 245 patients who were included in the study, and of the 222 patients who attended the 24-week follow-up visit

Description of the healing process of clavicular fractures

After 6 months, 126 (57%) of the 222 patients had recovered completely, while 93 (42%) were still not fully recovered. 3 patients did not answer this question. Nonunion occurred in 15 of 222 (7%). The median time to complete recovery without sequelae was 4 months, with a minimum of 3 weeks.

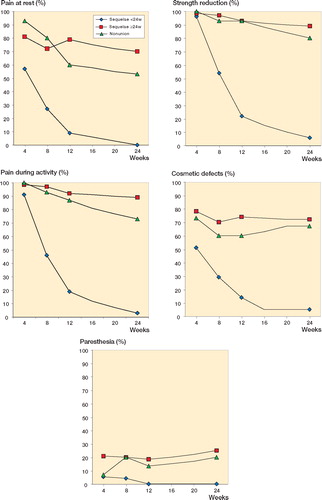

The patients were divided into 3 groups: those who recovered completely in less than 6 months, those with symptoms still present at 6 months, and those who developed nonunion. All patients with nonunion had some degree of remaining symptoms. The time course of 5 symptoms (pain at rest, pain during activity, strength reduction, paresthesia, cosmetic defects) in the 3 groups is given in .

Figure 1. Symptoms of clavicular fractures. Relative frequency (%) of patients with different types of symptoms at follow-up visits 4, 8, 12 and 24 weeks after injury. The patients were divided into three different subgroups:sequelae for < 6 months, sequelae for ≥ 6 months, and nonunion

Pain during activity was experienced initially by nearly all patients, but the rate fell rapidly during the first 3 months for those whose symptoms lasted for less than 6 months. In the other 2 groups, pain during activity persisted in 72% (nonunions) and 89% of the patients. The pain originated only from the clavicle. The same pattern was seen for strength reduction. The frequency of remaining paresthesia was low in patients who recovered completely before 6 months, while about 20% of patients who reported late sequelae or had a nonunion experienced paresthesia. In the group who had symptoms at 6 months, 80% experienced cosmetic defects, while the corresponding proportion among patients with nonunion was only slightly less. This perception persisted for the whole follow-up time, while for those in the subgroup without sequelae at 6 months the proportion who reported cosmetic defects declined from about 50% at 4 weeks to almost zero at final follow-up. The same pattern was seen for pain at rest.

Risk factors associated with the outcome of clavicular fractures ()

Age was a significant risk factor for all of the out-come variables except nonunion. There was no significant association between gender or smoking and the outcome variables. However, 13% of the women developed a nonunion while this was the case in 3% of men. Smokers did not have a higher occurrence of nonunions. The locations of the nonunions in women were 2 in the acromial part and 7 in the middle part, while for men the locations were 3 in the acromial part, 2 in the middle part and 1 in the sternal part. Fracture in the middle of the clavicle was a risk factor for a bad cosmetic result, elevating the estimated risk by nearly 60% compared to an acromial fracture. An elevated risk was also associated with a comminute fracture type, in particular one with transversally placed fragments. Comminute fracture type was a risk factor for all symptoms and sequelae except paresthesia and nonunion. Displacement between the main fragments in the anteroposterior view and the 45° tilted view was associated with an increased risk of remaining symptoms, especially if displacement occurred in both projections at the same time. Shortening in either of the two views was not a significant risk factor for remaining symptoms at 6 months.

Table 2a. Outcome variables at 24 weeks after the clavicular injury by patient characteristics at the time of injury

Table 2b. Outcome variables at 24 weeks after the clavicular injury by patient characteristics at the time of injury

In order to illustrate the importance of some of the risk factors found in this study, we compared some patient groups. For example, when comparing fractures in women where the displacement was 1 bone width or more in any projection (0 or 45°) at baseline vs. women without displacement, the estimated relative risk of sequelae at 6 months was 2.2 (95% CI: 1.2–4.1). When comparing women with displacement of more than 1 bone width in any projection vs. men with displacement of more than 1 bone width in any projection, the relative risk of sequelae after 6 months was 1.5 (CI: 1.0–2.1). Finally, the estimated relative risk was 2.1 (CI: 1.2–3.5) when comparing patients < 50 years of age with displacement of half a bone width or more in any projection vs. patients < 25 years of age with displacement of half a bone width or more.

Discussion

Our main finding was that almost half of the patients had symptoms from the fracture of the clavicle even 6 months after injury. The proportion of symptomatic patients was greater than expected on the basis of previous reports (Blömer et al. 1977, Eskola et al. 1986, Hill et al. 1997, Nordqvist et al. 1997, 1998, Robinson Citation1998, Oroko et al. 1999). The discrepancy in the frequency of long-lasting symptoms between our study and previous studies is possibly due to our prospective study design and the more extensive evaluation of our patients.

We cannot explain why nonunion was more common in women. Contrary to what Robinson (Citation1998) found in a consecutive, retrospective study of 1000 patients, all of our patients with nonunions had persisting symptoms. In his series 9 of 19 nonunions of the acromial part and 1 of 29 in the middle part, which were also displaced initially, had no symptoms. In another retrospective study by Nordqvist et al. (1993) 2 of 10 nonunions of fractures in the acromial part had moderate pain.

Patients who experienced pain at rest and patients who were not satisfied with the cosmetic outcome had the same time course pattern. Our findings suggest that if the patient experiences pain at rest and/or cosmetic defects more than 3 months after the fracture, an active treatment regime should be considered. Eskola et al. (1986) examined 89 of 118 patients 2 years after 1 clavicular fracture. They found that patients with a primary dislocation exceeding 15 mm or shortening at follow-up had more pain. 11 patients had abduction weakness, 8 of whom had a shortening of unknown length. Nordqvist et al. (1997) evaluated the incidence and clinical significance of post-fracture shortening of the clavicle in 83 patients at least 5 years after injury. It was found that shortening was most common after displaced midclavicular fractures. It should be noted that 42 of the 83 patients were under 15 years of age. In a retrospective study, Hill et al. (1997) found that initial shortening at the fracture of ≥ 20 mm was associated with nonunion and an unsatisfactory result, while final shortening of ≥ 20 mm was associated with an unsatisfactory result, but not with nonunion. All of these fractures were completely displaced. Whether it was the displacement and/or the shortening that gave the unsatisfactory result is unclear. Oroko et al. (1999) found that 3 of 41 patients had shortening of ≥ 15 mm. These authors could not demonstrate any relationship between clavicular shortening and shoulder function (Constant score).

We found that primary displacement was the strongest radiographic risk factor for sequelae at 6 months. Historically, treatment and follow-up after clavicular fractures have been focused on nonunions. Our observations indicate that a more active approach, including surgery at an early stage, may be worth considering in certain groups of patients.

- Ali Khan M A, Lucas K H. Plating of fractures of the middle third of the clavicle. Injury 1978; 9: 263–7

- Blömer J, Muhr G, Tscherne H. Ergebnisse konservativ und operativ behandelter Schlüsselbeinbrüche. Unfallheilkunde 1977; 80: 237–42

- Echtermeyer V, Zwipp H, Oester H J. Fehler und Gefahren in der Behandlung der Frakturen und Pseudarthrosen des Schlüsselbeins. Langenbecks Arch Surg 1984; 364 351–4

- Effenberger T. Clavikelfrakturen: Behandlung nach Unter-suchungsergebnisse. Der Chirurg 1981; 52: 121–4

- Eskola A, Vainionpää S, Myllynen P, Pätiälä H, Rokkanen P. Outcome of clavicular fracture in 89 patients. Arch Orthop Traumat Surg 1986; 105: 337–8

- Hill J, McGuire M, Crosby L. Closed treatment of displaced middle-third fractures of the clavicle gives poor results. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1997; 79(4)537–9

- Jupiter J, Leffert R D. Non-union of the clavicle. Associated complications and surgical management. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1987; 69(5)753–60

- Kohaus H, Sasse W. Claviculafraktur - Indikation zur kon-servativen und operativen Behandlung. Dtsch Zeitschrift Sportsmedizin 1980; 31: 114–20

- Langenberg von R. Therapy of clavicular fractures and injuries of adjacent joints: when is a surgical, when is a conservative procedure indicated?. Beitr Orthop Teumatol 1987; 34: 124–31

- Nordqvist A, Petersson C, Redlund-Johnell I. The natural course of lateral clavicle fracture. 15 (11–21) year follow-up of 110 cases. Acta Orthop Scand 1993; 64: 87–91

- Nordqvist A, Redlund Johnell I, von Scheele A, Petersson C. Shortening of clavicle after fracture. Incidence and clini-cal significance, a 5-year follow-up of 85 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 1997; 68(4)349–51

- Nordqvist A, Petersson C, Redlund-Johnell I. Mid-clavicle fractures in adults: End result study after conservative treatment. J Orthop Trauma 1998; 12(8)572–6

- Nowak J, Mallmin H, Larsson S. The aetiology and epidemiology of clavicular fractures. A prospective study during a two-year period in Uppsala. Sweden Injury 2000; 31(5)353–8

- Oroko P, Buchan M, Winkler A, Kelly I. Does shortening matter after clavicular fractures?. Bull Hosp Jt Dis 1999; 58(1)6–8

- Paffen P J, Jansen E W. L. Surgical treatment of clavicular fractures with Kirschner wires: A Comparative study. Arch Chir Neerlandicum 1978; 30: 43–53

- Robinson C M. Fractures of the clavicle in the adult. Epidemiology and classification. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1998; 80(3)476–84

- Rowe C R. An atlas of anatomy and treatment of midclavicular fractures. Clin Orthop 1968, 58 29–42

- Schmit-Neuerburg K P, Weiss H. Konservative Therpie und Behandlungsergebnisse der Claviculafrakturen. Hefte Unfallheilkunde 1982; 160: 55–75

- Stanley D, Norris S H. Recovery following fractures of the clavicle treated conservatively. Injury 1988; 19: 162–4

- Zenni E J, Jr, Krieg J K, Rosen M J. Open reduction and internal fixation of clavicular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1981; 63: 147–51