Abstract

Background Closed and open grade I (low-energy) tibial shaft fractures are a common and costly event, and the optimal management for such injuries remains uncertain.

Methods We explored costs associated with treatment of low-energy tibial fractures with either casting, casting with therapeutic ultrasound, or intramedullary nailing (with and without reaming) by use of a decision tree.

Results From a governmental perspective, the mean associated costs were USD 3,400 for operative management by reamed intramedullary nailing, USD 5,000 for operative management by non-reamed intramedullary nailing, USD 5,000 for casting, and USD 5,300 for casting with therapeutic ultrasound. With respect to the financial burden to society, the mean associated costs were USD 12,500 for reamed intramedullary nailing, USD 13,300 for casting with therapeutic ultrasound, USD 15,600 for operative management by non-reamed intramedullary nailing, and USD 17,300 for casting alone.

Interpretation Our analysis suggests that, from an economic standpoint, reamed intramedullary nailing is the treatment of choice for closed and open grade I tibial shaft fractures. Considering financial burden to society, there is preliminary evidence that treatment of low-energy tibial fractures with therapeutic ultrasound and casting may also be an economically sound intervention.

Of tibial fractures, closed and grade I open fractures, also known as low-energy fractures (Toivanen et al. Citation2001), are the most common (Heckman and Sarasohn-Khan Citation1997). Surgeons have had divided opinions as to what management strategies might best reduce fracture healing time and minimize complications of closed and open grade I tibial fractures, and also regarding their potential cost implications (Littenberg et al. Citation1998, Coles and Gross Citation2000).

While most of these fractures can be treated with casting or functional braces, operative fixa-tion with intramedullary nails has become increasingly popular. Casting is typically perceived as less costly and invasive, whereas operative care is perceived as being more effective in reducing healing time—but at the expense of greater cost and risk of complications. In an effort to optimize nonoperative management, adjunctive modalities have been proposed, such as therapeutic ultrasound. There is some evidence that the addition of therapeutic ultrasound may reduce healing time and complication rates compared to casting alone (Cook et al. Citation1997, Busse et al. Citation2002); however, there are additional costs associated with its use.

Scarcity of resources is an accepted reality in healthcare, and there is a need to consider both clinical outcomes and economic factors when evaluating treatment options. There is, however, a paucity of data on the costs of many orthopedic procedures, including management of tibial fractures (Maniadakis and Grey Citation2000, Bozic et al. Citation2003, Haentjens and Annemans Citation2003). In this study, we present an economic analysis of current competing strategies for the management of patients with closed and open grade I tibial shaft fractures.

Methods

We performed our economic analysis from the standpoint of the local government (the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care) and of society. The governmental perspective included all direct costs to healthcare (). Current guidelines recommend a comprehensive societal perspective including out-of-pocket expenses and lost productivity for family members and other caregivers (Weinsten and Fineberg Citation1980). Such detailed economic data are not readily available within the existing literature on tibial fracture management. As such, productivity losses were calculated as proportional to time off work associated with each treatment strategy, based on time to fracture healing. Studies of populations in the US and the UK have found that the indirect costs of tibial fracture management are at least twice that of the direct healthcare costs, especially for those carrying out physical labor (Downing et al. Citation1997, Heckman and Sarasohn-Khan Citation1997, MacKenzie et al. Citation1998). Current guidelines recommend a comprehensive societal perspective including out-of-pocket expenses and lost productivity for family members and other caregivers (Weinstein and Fineberg Citation1980). Such detailed economic data are not readily available in the existing literature on tibial fracture management. As such, productivity losses were calculated as being proportional to time off work associated with each treatment strategy, based on time to fracture healing. All costs are expressed in American dollars (September 2004) unless otherwise specified.

Table 1. Resource unit costs

Unit costs

Hospital costs and healthcare fees were obtained from the Ontario Physician's Schedule of Benefits (Ontario Ministry of Health Citation2003). The costs of prescribed drugs were obtained from city hospital pharmacy records (Hamilton, Ontario). Fees associated with hospitalization were calculated by estimating the weighted average orthopedic ward fee per day from a city hospital (Hamilton, Ontario) (). The cost of therapeutic ultrasound units (the Sonic Accelerated Fracture Healing System (SAFHS 2A)) was obtained from Smith & Nephew (Memphis, TN, USA). Resource utilization for patients treated for tibial fractures was obtained from a review of the relevant literature (Sprague and Bhandari Citation2002), and by consultation with an experienced trauma surgeon ().

Table 2. Total estimated costs. Treatment costs are presented (in CAD), with cost to productivity in brackets.

We made the following assumptions: (1) 3 radio-graphic examinations would be required for each operative procedure (before, during, and after), and 2 would be required for each conservative procedure (before and after); (2) fracture clinic frequency was assumed to be at 2 weeks, and then for each subsequent month until radiographic healing (for closed management strategies), as opposed to 2 weeks and then every 3 months until radiographic healing occurred (for operative management).

Productivity losses

Tibial fractures result in substantial loss of work hours, particularly for those whose work involves physical labor. The time to fracture union has been found to be closely related to the duration of disability (Fourie and Bowerbank Citation1997, Tornetta and Tiburzi Citation2000), and this assumption was used to estimate productivity losses. According to Statistics Canada, the average wage for individuals in the Hamilton-Wentworth area (Ontario, Canada) in 2002 was USD 521/week, and the average unemployment rate was 6%. This unemployment rate was taken into account when determining productivity losses ().

Literature search strategy

Two of the authors (JWB, SS) independently identified relevant studies on treatment of low-energy tibial fractures by conducting a systematic search of MEDLINE (from 1966 to October 2003) with the following terms: “fracture healing AND tibia OR tibial shaft”. The results were limited to English-language studies involving human subjects. We conducted an additional search on MEDLINE using the term “tibial shaft”, limited to either randomized clinical trials or meta-analyses. This resulted in 902 original articles. The bibliographies of all retrieved publications were reviewed for additional articles that might be relevant, and the files of the authors were also searched, which yielded an additional 6 articles.

JWB and SS independently assessed the titles of electronic articles to determine whether the study involved treatment of closed or grade I open tibial fractures with either casting, casting and therapeutic ultrasound, or intramedullary nailing (reamed or unreamed). If the title suggested any possibility that the study might be relevant, the abstract was retrieved. We retrieved potentially eligible abstracts for review in duplicate. Agreement between JWB and SS on studies selected for retrieval was good (kappa = 0.78; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.75–0.81).

Data abstraction

In order to reduce bias, we decided a priori to abstract data only from original prospective studies; however, we had difficulty in determining from a number of observational trials whether the data had been collected prospectively or retrospectively. Thus, we limited our sources of data to randomized clinical trials. JWB and SS independently abstracted data from each eligible study. Data abstracted included treatment groups, interventions, duration of hospitalization, rates of complications (deep infections, delayed union, nonunion, deep vein thrombosis, compartment syndrome, implant failure), and time to fracture healing ().

Table 3. Summary of eligible trialsa

Economic analysis

We performed an economic analysis for four competing treatment strategies of closed or grade I open tibial fractures: (1) casting alone, (2) casting with therapeutic ultrasound, (3) operative treatment with non-reamed intramedullary nailing, and (4) operative treatment with reamed intramedullary nailing. The time to fracture union (radiographically) was used as the measure of effectiveness. Given the multiple clinical alternatives, each with the potential to result in a number of outcomes, we used a decision tree to perform all cost analyses (Data 4.0.7; TreeAge Software Inc., Williamstown, MA, USA). We began our decision tree with a defined category of patients (low-energy tibial fracture), which led to four possible treatment paths termed “chance nodes” (). We obtained probabilities for the decision tree from randomized clinical trials. Given the limited information available on the use of ultrasound and casting to treat low-energy tibial fractures, we acquired missing data from trials reporting casting alone, as indicated in . We believed this assumption to be conservative as there is some evidence that the use of therapeutic ultrasound as an adjunct to casting alone results in improved outcomes (Cook et al. Citation1997, Busse et al. Citation2002, Frankel and Mizuho Citation2002).

We conducted sensitivity analyses through Monte Carlo simulations run on models developed for both the governmental and the societal perspective. Monte Carlo modeling is a form of probabilistic sensitivity analysis in which theoretical patients pass through a model, with transitions at each cycle decided by a random number generator and the probabilities associated with that transition. The purpose of the simulation is to arrive at an estimate of the precision of the outcome of interest (Drummond et al. Citation1998). For each treatment arm, 10,000 patients were simulated. For sensitivity analyses of these simulations, we calculated the standard deviation surrounding all treatment and productivity costs assuming 50% increases and 50% decreases.

Results

Literature search

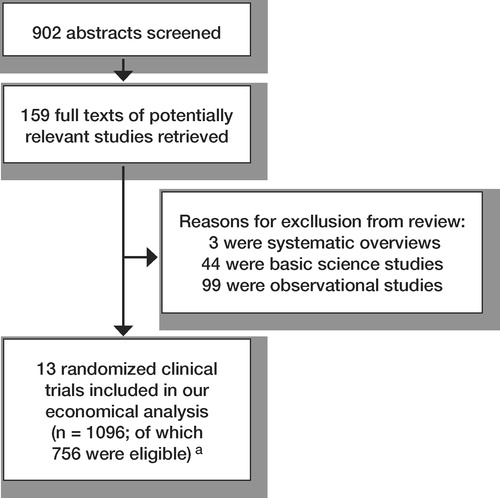

Our search resulted in 159 articles being retrieved in full text for review, of which 115 were potentially eligible for data abstraction. There were three systematic overviews, 13 randomized clinical trials (van der Linden and Larsson Citation1979, Abdel-Salam et al. Citation1991, Hooper et al. Citation1991, Heckman et al. Citation1994, Chiu et al. Citation1996a, Citationb, Court-Brown et al. Citation1996, Blachut et al. Citation1997, Cook et al. Citation1997, Keating et al. Citation1997, Finkemeier et al. Citation2000, Karladani et al. Citation2000, Nassif et al. Citation2000) (), and 99 observational studies ().

Figure 1. Stages of screening studies for inclusion in our economic analysis. aSubjects in trials who presented with a tibial fracture that was not closed or grade I open, or those who were managed with treatment other than casting, casting with therapeutic ultrasound, reamed or non-reamed intramedullary nailing, were not eligible for inclusion in our economic analysis.

Table 4. Characteristics of eligible trials

Perspective 1: governmental

Our economic analysis revealed that treatment of closed or open grade I tibial shaft fractures with reamed intramedullary nailing was the most economical choice from a governmental point of view. Monte Carlo simulation found that the mean associated costs were USD 3,365 (SD 1,425) for operative management by reamed intramedullary nailing, USD 5,041 (SD 1,363) for operative management by non-reamed intramedullary nailing, USD 5,017 (SD 1,370) for casting, and USD 5,312 (SD 1,474) for casting with therapeutic ultrasound. Strategy selection frequency of Monte Carlo simulations revealed that reamed intramedullary nailing resulted in the optimal economic path in 57% of simulations; other treatment options were each selected at a frequency between 13% and 16%.

Perspective 2: societal

From the perspective of burden on society, our economic analysis found that treatment of closed or open grade I tibial shaft fractures with reamed intramedullary nailing or casting and therapeutic ultrasound were the most economical choices. Our sensitivity analysis favored operative management by reamed intramedullary nailing (USD 12,449; SD 4,894) and suggested that casting with therapeutic ultrasound may hold promise (USD 13,266; SD 3,692), with both these options being favored over operative management by non-reamed intramedullary nailing (USD 15,571; SD 4,293) and casting alone (USD 17,343; SD 4,784). Strategy selection frequency revealed that reamed intramedullary nailing resulted in the optimal economic path in 43% of simulations, whereas casting and ultrasound was the optimal economic path in 31% of simulations.

Discussion

Our analysis suggests that, from a governmental standpoint, in which only direct healthcare costs are considered, treatment of closed or open grade I tibial shaft fractures with reamed intramedullary nailing yields substantial economic benefits over competing treatment strategies. From a societal standpoint, when time lost at work is included, treatment with either reamed intramedullary nailing or ultrasound and casting appear to offer substantial benefit over non-reamed nailing or casting alone.

Our study has some limitations. To build our economic models, we abstracted outcome data from small randomized clinical trials; however, we limited our data to prospective trials only, and our estimates of treatment and productivity costs are similar to other economic analyses (Downing et al. Citation1997, Heckman and Sarasohn-Khan Citation1997, Toivanen et al. Citation2000, Sprague and Bhandari Citation2002). Furthermore, only 2 randomized clinical trials (which reported on a shared data set) were available to acquire probabilities for the use of casting and therapeutic ultrasound, leaving many assumptions to be made. The determination of patient productivity losses was limited by insufficient information on time lost from leisure activities, unpaid production time, and productivity losses from family members or other caregivers. It was also assumed that patients would not be replaced at their jobs, and that they would return to work when their fracture had healed. This may have resulted in inaccurate estimates of productivity losses in cases in which workers were replaced, or could return to work to less physically demanding positions before their fracture had healed. Furthermore, the impact of non-injury related variables has been established in predicting return to work following fractures (MacDermid et al. Citation2002), and these were not considered in our model.

There have been some studies that are relevant to our analysis; however, none were based on a Canadian model of healthcare, which makes direct comparisons difficult. In Finland, Toivanen and colleagues (Citation2000) retrospectively examined the costs incurred from treatment of 26 low-energy tibial fractures with casting versus 51 equivalent fractures treated with reamed intramedullary nailing. As in our analysis, these authors noted similar direct costs (USD 4,733 (FIM 22,920) per patient for casting versus USD 5,565 (FIM 26,952) per patient for nailing), but found substantial economic advantages associated with the use of reamed intramedullary nailing when indirect costs were included (USD 24,879 (FIM 120,486) per patient for casting versus USD 16,979 (FIM 82,224) per patient for nailing). In the UK, Downing and colleagues (Citation1997) undertook a retrospective economic analysis of 39 closed or grade I tibia fractures treated with reamed intramedullary nailing (n = 21) or casting (n = 18). They noted a significant advantage in favor of casting for direct costs (USD 4,019 (GBP 2,226) per patient for casting versus USD 6,728 (GBP 3,727) per patient for nailing), but the difference in treatment cost was not statistically significant when indirect costs were also considered (USD 12,294 (GBP 6,810) per patient for casting versus USD 11,901 (GBP 6,592) per patient for nailing).

Heckman and Sarasohn-Kahn (Citation1997) presented three economic models based on an American system of healthcare, with 1,000 simulated patients with tibial shaft fractures treated with either casting or intramedullary nailing. Their model, which incorporated direct healthcare costs, outpatient costs and workers' compensation costs, indicated that when low-intensity ultrasound was used adjunctively with casting there were cost savings of approximately 15,000 (USD 1,997) per case. Savings were attributed to reduced secondary procedures, and reduced workers' compensation costs due to increased healing time.

Our analysis indicates that, from an economic standpoint and from both a governmental and societal point of view, reamed intramedullary nailing is the treatment of choice for closed and open grade I tibial shaft fractures. There is preliminary evidence that from the aspect of burden on society, treatment of low-energy tibial fractures with therapeutic ultrasound and casting may also be an economically sound intervention. A large, prospective trial is needed to further define the clinical effectiveness of therapeutic ultrasound on healing of closed and open grade I tibial shaft fractures, and to ascertain the true associated economic costs of this modality.

Competing interests not declared.

Authors' contributions

Jason W. Busse led the writing of the manuscript and, with Mohit Bhandari, developed the concept for the study. Sheila Sprague assisted in article selection and data abstraction. Ana P. Johnson-Masotti and Amiram Gafni provided methodological input for the economic analysis. All authors contributed to the study design, in revising the manuscript, and in reviewing the final manuscript.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Professor Bernie O'Brien—a teacher and mentor.

The project was funded by a grant (“Hip Hip Hooray”) from the Canadian Orthopaedic Association. Jason Busse is funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Fellowship Award. Mohit Bhandari is funded, in part, by a Detweiler Fellowship from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Ana Johnson-Masotti is funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award.

- Abdel-Salam A, Eyres K S, Cleary J. Internal fixation of closed tibial fractures for the management of sports injuries. Br J Sports Med 1991; 25: 213–7

- Blachut P A, O'Brien P J, Meek R N, Broekhuyse H M. Interlocking intramedullary nailing with and without reaming for the treatment of closed fractures of the tibial shaft. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1997; 79: 640–6

- Bozic K J, Rosenberg A G, Huckman R S, Herndon J H. Economic evaluation in orthopaedics. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2003; 85: 129–42

- Busse J W, Bhandari M, Kulkarni A V, Tunks E. The Effect of Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Therapy on Time to Fracture Healing: a Meta–Analysis. CMAJ 2002; 166: 437–41

- Chiu F Y, Lo W H, Chen C M, Chen T H, Huang C K. Treatment of unstable tibial fractures with interlocking nail versus Ender nail: a prospective evaluation. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei) 1996a; 57: 124–33

- Chiu F Y, Lo W H, Chen C M, Chen T H, Huang C K. Unstable closed tibial shaft fractures: a prospective evaluation of surgical treatment. J Trauma 1996b; 40: 987–91

- Coles C P, Gross M. Closed tibial shaft fractures: management and treatment complications. A review of the prospective literature. Can J Surg 2000; 43: 256–62

- Cook S D, Ryaby J P, McCabe J, Frey J J, Heckman J D, Kristiansen T K. Acceleration of tibia and distal radius fracture healing in patients who smoke. Clin Orthop 1997, 337: 198–207

- Court-Brown C M, Will E, Christie J, McQueen M M. Reamed or unreamed nailing for closed tibial fractures. A prospective study in Tscherne C1 fractures. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1996; 78: 580–3

- Downing N D, Griffin D R, Davis T R. A comparison of the relative costs of cast treatment and intramedullary nailing for tibial diaphyseal fractures in the UK. Injury 1997; 28: 373–5

- Drummond M F, O'Brien B, Stoddart G L, Torrance G W. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, Toronto 1998

- Finkemeier C G, Schmidt A H, Kyle R F, Templeman D C, Varecka T F. A prospective, randomized study of intramedullary nails inserted with and without reaming for the treatment of open and closed fractures of the tibial shaft. J Orthop Trauma 2000; 14: 187–93

- Fourie J A, Bowerbank P. Stimulation of bone healing in new fractures of the tibial shaft using interferential currents. Physiother Res Int 1997; 2: 255–68

- Frankel V H, Mizuho K. Management of non-union with pulsed low-intensity ultrasound therapy-international results. Surg Technol Int 2002; 10: 195–200

- Haentjens P, Annemans L. Health economics and the orthopaedic surgeon. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2003; 85: 1093–9

- Heckman J D, Sarasohn-Kahn J. The economics of treating fracture healing. Bull Hosp Jt Dis 1997; 56: 63–72

- Heckman J D, Ryaby J P, McCabe J, Frey J J, Kilcoyne R F. Acceleration of tibial fracture-healing by non-invasive, low-intensity pulsed ultrasound. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1994; 76: 26–34

- Hooper G J, Keddell R G, Penny I D. Conservative management or closed nailing for tibial shaft fractures. A randomised prospective trial. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1991; 73: 83–5

- Karladani A H, Granhed H, Edshage B, Jerre R, Styf J. Displaced tibial shaft fractures: a prospective randomized study of closed intramedullary nailing versus cast treatment in 53 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71: 160–7

- Keating J F, O'Brien P J, Blachut P A, Meek R N, Broekhuyse H M. Locking intramedullary nailing with and without reaming for open fractures of the tibial shaft. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1997; 79: 334–41

- Littenberg B, Weinstein L P, McCarren M, Mead T, Swiontkowski M F, Rudicel S A, Heck D. Closed fractures of the tibial shaft. A meta-analysis of three methods of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1998; 80: 174–83

- MacDermid J C, Donner A, Richards R S, Roth J H. Patient versus injury factors as predictors of pain and disability six months after a distal radius fracture. J Clin Epidemiol 2002; 55: 849–54

- MacKenzie E J, Morris J A, Jr, Jurkovich G J, Yasui Y, Cushibng B M, Burgess A R, DeLateur B J, McAndrew M P, Swiontkowski M F. Return to work following injury: the role of economic, social, and job-related factors. Am J Public Health 1998; 88: 1630–7

- Maniadakis N, Gray A. Health economics and orthopaedics. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2000; 82: 2–8

- Nassif J M, Gorczyca J T, Cole J K, Pugh K J, Pienkowski K D. Effect of acute reamed versus unreamed intramedullary nailing on compartment pressure when treating closed tibial shaft fractures: a randomized prospective study. J Orthop Trauma 2000; 14: 554–8

- Ontario Ministry of Health. Schedule of Benefits. Ontario Ministry of Health, Canada 2003

- Sprague S, Bhandari M. An economic evaluation of early versus delayed operative treatment in patients with closed tibial shaft fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2002; 122: 315–23

- Toivanen J A, Hirvonen M, Auvinen O, Honkonen S E, Jartvinen T L. Koivisto A. M, Jarvinen M J. Cast treatment and intramedullary locking nailing for simple and spiral wedge tibial shaft fractures–a cost benefit analysis. Ann Chir Gynaecol 2000; 89: 138–42

- Toivanen J A, Honkonen S E, Koivisto A M, Jarvinen M J. Treatment of low-energy tibial shaft fractures: plaster cast compared with intramedullary nailing. Int Orthop 2001; 25: 110–3

- Tornetta P, Tiburzi D. Reamed versus non-reamed anterograde femoral nailing. J Orthop Trauma 2000; 14: 20–5

- van der Linden W, Larsson K. Plate fixation versus conservative treatment of tibial shaft fractures. A randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1979; 61: 873–8

- Weinstein M C, Fineberg H V. Clinical decision analysis. W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia 1980