Abstract

Background Outcome measurement of shoulder arthroplasty is not standardized. We compared 3 scores and 1 evaluation form.

Patients and methods We report on 35 hemiarthroplasties of the shoulder (32 cementless). Mean age of the patients was 62 (29–87) years. After a mean follow-up of 6 years (range 2–18 years) patients were evaluated with the Neer score, the Constant-Murley score, the score of the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA) and the Society of Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Basic Shoulder Evaluation Form. We also performed radiographic evaluation and sonographic evaluation of the rotator cuff.

Results Although pain relief and patient satisfaction were promising, the overall results of the respective score showed low values (Neer score 56/100 points, Constant-Murley score 43/100 points, and UCLA score 19/35 points on average).

Interpretation We recommend choice of a score with a high impact of pain and patient satisfaction. Furthermore, ability to cope with activities of daily living should be of more importance than strength.

For outcome assessment of shoulders, several methods have been used since Codman first introduced outcome analysis in the early 20th century. These range from single parameter tests over scoring systems to questionnaires (Kuhn and Blasier Citation1998). Each system is based on different parameters, and this makes it difficult to compare the different methods of outcome measurement and thus judge the results obtained.

Evaluation of the outcome after prosthetic replacement of the shoulder joint has not been standardized, so comparisons of the results of different studies are not satisfactory. Some scores only evaluate pain, range of motion and patient satisfaction without any scoring system (Constant and Murley Citation1988). Others use questionnaires or assess certain activities of daily living (Constant and Murley Citation1988, Kay and Amstutz Citation1988, Cofield Citation1994, Conboy et al. Citation1996, Beaton and Richards Citation1998, Kuhn and Blasier Citation1998). Most scores evaluate the outcome based on the performance of a young, healthy shoulder, a situation rarely encountered in patients eligible for shoulder replacement.

We assessed shoulder replacements using three scoring systems and one evaluation system. The main aim was to determine which assessment protocol most accurately reflects the clinical results obtained.

Patients and methods

Of 53 hemiprostheses of the shoulder implanted at our institution, we could evaluate 35 clinically and radiographically. All patients received prostheses of the Neer type (3M, Switzerland). 3 implants were cemented and the rest were cementless. The indication for arthroplasty was rheumatoid arthritis in 14 cases (10 women), primary and secondary osteoarthritis in 11 cases (8 women; 2 patients after infectious arthritis, 1 patient after rotational osteotomy following osteonecrosis) and posttraumatic destruction of the shoulder joint in 10 shoulders (6 women).

3 patients received bilateral prostheses: 2 patients because of degenerative changes and 1 because of rheumatoid disease. Pain was the main indication for surgery. Age at the time of operation was on average 62 (29–87) years. The osteoarthritis patients were older than the rheumatoid patients (mean 70 and 59 years, respectively) and those who received an implant after traumatic destruction of the humeral head had a mean age of 57 years.

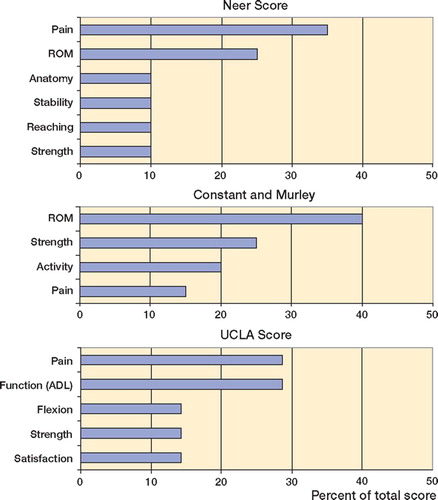

Follow-up examinations consisted of clinical, radiographic and sonographic evaluation and were performed on average 6 (2–18) years after surgery. We performed clinical evaluation using the Neer score, the UCLA score, the score of Constant and Murley () and the American Society of Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Basic Shoulder Evaluation forms:

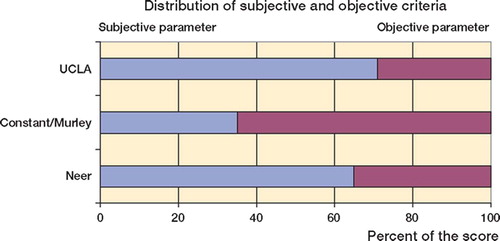

1. The Neer score assesses 65% subjective parameters and 35% objective parameters (Neer, Citation1970).

2. The score of Constant and Murley combines 35% subjective parameters (pain 15%, tasks of daily living 20%) and 65% objective parameters (ROM 40%, strength 25%) with a maximum of 100 points.

3. The UCLA score evaluates pain, function, active flexion, strength, and satisfaction with a maximum of 35 points.

4. The American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Basic Evaluation assesses pain, active and passive range of motion, strength, stability, and activities of daily life. As this evaluation system lacks a final numeric scale, no absolute score value can be presented or directly compared to other scoring systems.

Radiographic assessment was performed with the score presented by Neer et al. (Citation1982), where the glenoid implant, the humeral implant, the position of the implants, and the presence of ectopic bone formation are evaluated. Results were related to the clinical outcome. Since it has been reported that disruption of the rotator cuff can influence the results of shoulder arthroplasty, we assessed the integrity of the rotator cuff by sonographic investigation at the time of follow-up.

Statistics

Statistical evaluation was performed with SPSS version 8.0. Statistical comparison of the different patient groups was not justified as the numbers of patients in each group were too low (10, 11 and 14).

Results

Clinical results

The results of the different scores showed low values for many patients (mean values: Neer score 56/100 points, Constant-Murley score 43/100 points and UCLA score 19/35 points. This was not consistent with the clinical impression; most of the patients expressed a high degree of satisfaction with their outcome (). As pain was the decisive factor leading to surgery, its presence or absence at follow-up could be used as an indicator of the success of surgery. At follow-up, 22/35 shoulders had no or only slight pain. The figures were 11/14 in the RA group, 7/11in the OA group and 4/10 in the posttraumatic shoulders.

Table 1. Results of the Neer score, the score of Constant and Murley and the UCLA score for all patients and in the different diagnostic groups

Similar results were observed when the patient's response to the operation was assessed. At follow-up, 25/35 perceived their postoperative situation to be better or much better than before surgery. Of the rheumatoid arthritis patients, 12/14 felt better or much better postoperatively as compared to 8/11 of the osteoarthritis patients and 5/10 of the posttraumatic group.

Flexion and abduction were evaluated for all diagnostic groups. Surprisingly, the rheumatoid patients showed best results in flexion, 90° (40– 140) on average. While the OA-group achieved average values about 88° (30–140), the posttraumatic patients were limited in their elevation to 64° (20–110). In abduction the differences were less pronounced, with 70° (30–110) for the OA group, 66° (20–110) for the rheumatoid group and 56° (20–100) for the posttraumatic patients.

Rotator cuff deficiency appears to have influenced the results, since the nine patients with a sonographically verified tear of the rotator cuff (width < 1 cm) had lower scores (Neer 39 points, Constant-Murley 28 points and UCLA 14 points) than patients with an intact rotator cuff. Clinically and radiographically diagnosed arthrosis of the ipsilateral acromioclavicular joint had no influence on the outcome of the assessments.

Neer score

On average, the patients scored 56 (9–87) points of 100 possible. No excellent result was recorded. Average score in the RA group was 60 (22–82) points. Equal results were achieved by those patients who underwent the operation for osteoarthritic changes with 60 (14–87) points. The posttraumatic shoulder replacements showed the lowest values, with mean 45 (9–85) points ().

Table 2a. Results of different sections of the Neer score for different groups of patients

Constant-Murley score

Overall, this evaluation gave 43 points (of 100 possible) on average. Again, the OA patients showed the highest mean scores, 14 (13–75) points, followed by the RA group with an average of 42 (21– 63) points. With an average of 38 (10–81) points, the posttraumatic shoulder replacement patients achieved significantly lower values than the two other groups. Again, appreciable differences could be detected in the assessment of pain ().

Table 2b. Results of different sections of the Constant-Murley score for the different groups of patients

UCLA score

With the UCLA score, the distribution of results was similar to those recorded with other scores: 19 (3–32) of 35 possible points. The best results were obtained in the OA group, 21 (3–30) points, followed by the RA group with 20 (7–28) points and the patients with posttraumatic changes with 16 (5–32) points ().

Table 2c. Results of different sections of the UCLA score for different groups of patients

The rheumatoid arthritis patients were the most satisfied group (13/14), followed by the osteoarthritis patients (9/11). Of the posttraumatic patients, only 6/10 were satisfied with the result of their operation.

Society of American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Basic Shoulder Evaluation form

Although this form is very precise in its evaluation of function, range of motion and activities of daily life, it lacks a final numeric score. Thus, the results obtained cannot be compared with other scoring systems but the form is useful for comparison of pre- and postoperative results, for example. As mentioned above, 21/35 felt no pain or only slight pain (RA 11/14, OA 7/11, posttraumatic OA 3/10) at follow-up. Assessment of patient's response showed that three-quarters of the patients perceived their situation to be much better or better (RA 12/14, OA 8/11, posttraumatic OA 1/10).

Sonographic results

At time of follow-up, a sonographic control of the status of the rotator cuff was performed. In 9 patients, a rupture of the rotator cuff was diagnosed with a defect larger than 1 cm2 (1 RA, 3 OA, 5 posttraumatic OA). In 1 patient with rheumatoid arthritis, an open repair was performed 2 years after primary implantation.

Radiographic results

Evaluation of plain radiographs at followup was performed with the Neer score and showed 6 patients to have radiolucent lines (3 complete, 3 incomplete). 1 of these patients was symptomatic. 9 patients showed subluxations (7 superior, 2 anterior). Only in 2 of the 7 patients with superior subluxation a sonographically verified tear of the rotator cuff was found. 1 patient sustained an anterior dislocation, but refused revision. Ectopic bone formation was not detected in any of the patients. In 5 patients, radiographic signs of arthrosis of the acromioclavicular joint were detected, but this had no effect on the clinical results.

Complications

4 complications in the 53 patients requiring revision were recorded: 1 patient had rotator cuff deficiency (male, RA; re-operation 2 years after primary implantation), and 2 patients had persistent pain and lack of range of motion. The humeral head was changed to a smaller size in both cases, which resulted in relief of their symptoms. The fourth patient sustained a luxation of the shoulder. She lived in a home for elderly people and refused revision surgery. No revisions for loosening of the humeral component were done and no infections or intraoperative fractures were found.

Discussion

Evaluation of outcome is necessary in order to evaluate the results of one's own study, and to enable comparison of data from different centers. The greatest problem is, however, that the analysis of outcome has not been standardized in shoulder surgery.

Several scoring systems are presently in use. These can be divided into 3 major groups, quality-oflife measures, measures of general health, and shoulder assessments (Beaton and Richards Citation1998, Kuhn and Blasier Citation1998). Among the shoulder assessments, again, several types are in clinical use. Some provide a numerical scale to enable statistical comparisons; others are only guidelines for a comprehensive investigation of the shoulder and serve as an internal control for pre- and postoperative comparison and follow-up (Conboy et al. Citation1996). Quality- of-life measures and general health measures are gaining increasing importance in outcome research, since operations performed on parts of the body have a major effect on the general physical and psychological welfare of the patient (Ware and Shervourne Citation1992). On the other hand, coexisting parameters like co-morbidities or even emotional influences—independent from the shoulder problem—affect the quality of a patient's life and therefore may initiate bias and misinterpretation in quality-of-life assessmens after surgery. The forms of shoulder assessment we chose all consist of subjective and objective parameters. The selection of the scores was done according to the presence of subjective and objective assessment parameters, contents, feasibility in daily clinical routine (length of a singular assessment) and evaluation of pain ().

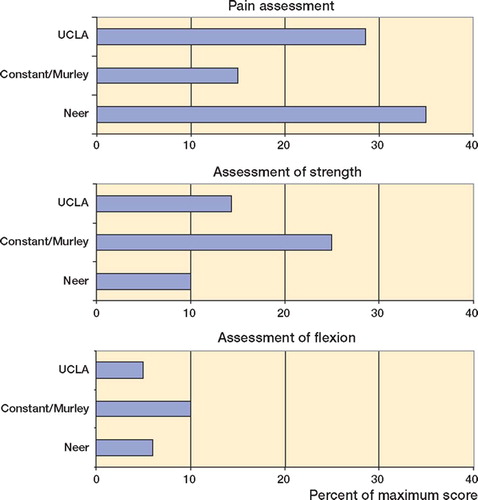

The scores used in the assessment of our patients (the Neer score, the UCLA shoulder assessment, the Constant-Murley score and the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Standardized Shoulder Assessment) are widely used instruments. As the study was aimed at evaluation of the shoulder after implantation of a prosthesis, we excluded the use of generic scores such as SF-36. All scores were designed to evaluate the status of the shoulder joint. The scores differ in their assembly and arrangement of the assessed categories in shoulder investigation. Function and activities of daily living were differentially defined by the respective authors. These circumstances made it difficult to compare the scores with each other directly. Three components were present in all 3 scores, and could thus be compared as to their influence on the outcome of each score: pain, strength and flexion. All other parameters were defined in different ways and were therefore not comparable ().

Figure 3. The results obtained in the different scores varied. So we tried to analyze the different scores. The three parameters present in all three scores were pain, strength and flexion. The three panels show the percentage significance of the three parameters in the different instruments.

As the Society of American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Basic Shoulder Evaluation form lacks a final numeric scale, we judged the other three scores used to be superior for interinstitutional and intrainstitutional comparisons. There were significant differences between the results of the various scores and the clinical evaluations. We observed high patient satisfaction, but the respective scores had low values. The patients who were evaluated (in particular, the patients with rheumatoid arthritis and the posttraumatic patients) showed better results in these scores, with a higher percentage in subjective parameters such as pain or patient response ().

As relief of pain and patient satisfaction are important goals in shoulder arthroplasty, this may lead to the recommendation to use assessments with a higher percentage of subjective parameters for the evaluation of outcome measurement in shoulder arthroplasty (Neer Citation1974, Neer et al. Citation1982, Sperling et al. Citation1998). For most assessments, the optimum score can only be achieved by a young, healthy, trained shoulder. This status cannot be expected of someone whose shoulder requires an implant.

We measured low scores in the assessment of strength in all forms of assessment (especially for the rheumatoid arthritis patients). This result shows that it is not the primary aim of shoulder arthroplasty to improve the strength of a patient, but to achieve pain relief and enable basic functions so that the patient will master the activities of daily living (Neer Citation1970, Citation1974, Neer et al. Citation1982). According to de Leest et al. (Citation1996), strength after shoulder arthroplasty is dependent on the orientation of the glenoid, the radius of the humeral head, and the position of the geometric center of the glenohumeral joint in relation to the scapula and in relation to the humeral shaft (Lee and Niemann Citation1994). Experimental changes to the geometric center in relation to the humeral shaft can cause differences in force of up to 300%.

Since few authors present absolute figures of their patients' assessments, a comparison against other results cannot easily be performed Lee and Niemann (Citation1994), Neer et al. (Citation1982),. Sperling et al. (1988) evaluated patients less than 50 years of age with the modified Neer score. Some authors have evaluated single parameters or specific tasks, or have assessed pain separated from function (Neer et al. Citation1982, Barrett et al. Citation1987, Cofield Citation1994). Other reports confirm our results for the different patient groups defined here, i.e. that osteoarthritic and rheumatoid patients perform better than posttraumatic patients (Sperling et al. Citation1998).

What follows is a list of considerations that may have a bearing on the outcome of a shoulder implant:

1. The achievement of pain relief may explain the good results in the RA group in all rating scales, especially in pain relief and patient satisfaction.

2. Tuberosity detachment, loosening, rotator cuff deficiency or inadequate rehabilitation have been reported reasons for lower scores in posttraumatic patients (Tanner and Cofield Citation1983, Ellmann et al. Citation1986, Laurence Citation1991, Compito et al. Citation1994, Dines and Warren Citation1994).

3. Postoperative range of motion is reported to be influenced by the height and version of the components (Dines and Warren Citation1994). If the position of the humeral prosthesis is too low, deltoid laxity and poor abduction fixation will occur, whereas a position that is too proud will result in superior instability and impingement.

4. Stability depends on meticulous reconstruction and rehabilitation of muscles, especially the supraspinatus and the anterior deltoid (Neer et al. Citation1982, Sperling et al. Citation1998).

Relief of pain—but only minor repair of func-tion—can be expected after a shoulder hemiprosthesis. For outcome measurement after shoulder arthroplasty, we recommend a score with a high proportion of subjective parameters such as pain and patient satisfaction, in addition to the evaluation of objective parameters such as strength and function. The state of the rotator cuff should be noted, as it influences the clinical success of the surgery. Considerable importance should be placed on preoperative patient information—regarding what can be expected in the fields of pain relief and function after implantation of a hemiprosthesis of the shoulder.

No competing interests declared.

Author contributions

PK performed the patients' follow-up investigations, data analysis and writing of the manuscript. AWH developed the idea for the study and AHW and CW operated on most of the patients and helped with the planning of the study. AHW and CW participated in analyzing and interpreting the data and in structurizing the study. All authors have full access to data and responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

- Barrett W P, Franklin J L, Jackins S E, Wyss C R, Matsen F A, 3rd. Total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1987; 69: 865–73

- Beaton D, Richards R R. Assessing the reliability and responsiveness of 5 shoulder questionnaires. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1998; 7/6: 565–72

- Cofield R H. Uncemented total shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 1994, 307: 86–93

- Compito C A, Self E B, Bigliani L U. Arthroplasty and acute shoulder trauma. Clin Orthop 1994, 307: 27–36

- Conboy V B, Morris R W, Kiss J, Carr A J. An evaluation of the Constant-Murley shoulder assessment. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1996; 78: 229–32

- Constant C R, Murley A H G. A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop 1988, 214: 160–4

- de Leest O, Rozing P M, Rzendaal L A, van der Helm F C T. Influence of glenohumeral prosthesis geometry and placement on shoulder muscle forces. Clin Orthop 1996, 330: 222–33

- Dines D M, Warren R F. Modular shoulder hemiarthroplasty for acute fractures. Clin Orthop 1994, 307: 18–26

- Ellmann H, Hanker G, Bayer M. Repair of the rotator cuff. Endresult study of factors influencing reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1986; 68: 1136–44

- Kay S P, Amstutz H C. Shoulder hemiarthroplasty at UCLA. Clin Orthop 1988, 228: 42–8

- Kuhn J E, Blasier R B. Assessment of outcome in shoulder arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am 1998; 29: 549–57

- Laurence M. Replacement arthroplasty of the rotator cuff deficient shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1991; 73: 916–9

- Lee D H, Niemann K M W. Bipolar shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 1994, 304: 97–107

- Neer C S. Displaced proximal humeral fractures. Part I. Classification and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1970; 52: 1077–89

- Neer C S. Replacement arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1974; 56: 1–13

- Neer C S, Watson K C, Stanton F J. Recent experiences in total shoulder replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1982; 64: 319–37

- Sperling J W, Cofield R H, Rowland C W. Neer hemiarthroplasty and Neer total shoulder arthroplasty in patients fifty years old or less. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1998; 80: 464–73

- Tanner M W, Cofield R H. Prosthetic arthroplasty for fractures and fracture-dislocations of the proximal humerus. Clin Orthop 1983, 179: 116–28

- Ware J E, Shervourne C D. The MOS 36-item shortform health survey (SF-36):I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30: 473–83