Abstract

Background and purpose Modern descriptions of the percutaneous triple hemisection technique for Achilles tendon lengthening do not take into account the axial twist in the ligament. We were concerned that technical failures of the lengthening technique might occur more often than has been reported, and analyzed the results of the triple hemisection technique in cadaveric tendons in quantitative and qualitative terms, focusing on insufficient or complete tenotomies.

Methods We performed a percutaneous triple hemisection of the Achilles tendon in 20 legs from adult cadavers, and measured the increase in ankle dorsiflexion in degrees, the length of the cuts in mm, and the depth of the cuts as a percentage of the total diameter of the tendon. Failure of the hemisection was defined as a sliding gap of ≤ 2 mm and/or a cut depth of ≤ 25% or < 75%.

Results 21 of the 60 hemisections failed. These failures occurred in 12 of the 20 legs, and included 1 complete tendon rupture and 3 near-ruptures with only a few connecting fibers left.

Interpretation Our findings support our hypothesis that technical failures in the triple hemisection procedure occur more often than acknowledged. Despite the scarce but good clinical results described in children, we suggest performing this technique as an open procedure, especially in cases where the boundaries of the tendon are less easily palpable (adults, obese children), and to use the largest possible distance between the hemisections.

Percutaneous Achilles tendon lengthening may be performed by the triple hemisection technique first mentioned by Hoke (Citation1931) and later described in detail by Hatt and Lamphier (Citation1947). The original description of the surgical technique took into account the “Manila rope-like” torsion of the Achilles tendon (White Citation1943), and included 3 hemisections (distally to proximally) in “anterior”, “slightly anterolateral”, and “posterotransverse” directions. Even though the torsion of the human Achilles tendon varies (Van Gils et al. Citation1996), the original surgical technique is often simplified to 3 transverse half-cuts (Bleck Citation1987). We encountered a few inadvertent results after this operation, and hypothesized that failures in the percutaneous triple hemisection technique may occur more often than is acknowledged. Thus, we analyzed (both quantitatively and qualitatively) each hemisection in the triple hemisection technique under controlled conditions in cadavers.

Material and methods

10 pairs of fresh-frozen legs from 5 male cadavers and 5 female cadavers were obtained from the Maryland State Anatomy Board. Mean age at time of death was 71 (48–90) years. None of the cadavers had any visually obvious presence of bone disease or ankle injury.

The tendon was palpated and the boundaries were marked. 2 observers measured the amount of dorsiflexion of the foot in flexion and extension of the knee with a goniometer, to the nearest 5 degrees. A scalpel with a no. 11 blade was inserted longitudinally in the midsubstance of the tendon at 3 levels and rotated 90 degrees around its longitudinal axis, the aim being to transect half of the tendon. The 3 incisions were placed 25 mm apart: the most proximal and distal were placed medially and the middle incision was placed laterally. The hemisections were made with the knee in extension and with the ankle in dorsiflexion. After the incisions, the foot was maximally dorsiflexed with manual force in a manner similar to the surgical routine. The 2 observers measured the amount of increased dorsiflexion attained by the procedure. Thereafter, the tendon was exposed by removal of all soft tissue. For each gap, the amount of lengthening was measured in mm with digital calipers. The depth of the cut was measured and the outcome parameter “cut depth” was defined as the depth of cut divided by the diameter of the tendon. This parameter was placed into one of the categories 0–25, 26–50, 51–75, or 76– 100%. Failure of the hemisection was defined as a lengthening of 2 mm or less, and/or a cut depth in the categories 0–25% or 76–100%, and/or (near-) rupture.

The average flexion and extension of the ankle were calculated using random effects analysis allowing 2 variance components (within and between subjects).

Results

The average increase in dorsiflexion was 13 (95% CI: 9–18) degrees with the knee in flexion and 14 (10–18) degrees with the knee in extension.

21 of all 60 hemisections in the 20 legs failed . These failures occurred in 12 of the 20 legs. The 12 legs with failures were from 8 cadavers.

Length of gap and depth of cut in 60 hemitenotomies (with failures in bold)

8 distal cuts failed in lengthening. 3 middle and 3 proximal cuts in 3 tendons lengthened so much that continuity of the tendon was only maintained by a few fibers. 2 proximal cuts were minimal (0– 25%), of which 1 did not slide. Of the 5 cuts in the 76–100% category, there was 1 complete rupture ().

Discussion

Our findings in this cadaver study of the percutaneous triple hemisection technique in Achilles tendon lengthening suggest that failure may be more common than expected. One- third of our hemisections followed by lengthening, under controlled laboratory conditions, resulted in “failure”. This contrasts with the results of Salamon et al. (Citation2006) who found in a study of 15 cadaver specimens that the hemisections averaged 50–60% of the tendon diameter, and concluded that reasonably accurate cuts can be made. Their study was focused on collateral damage of neurovascular structures by the hemisection only, however, and they did not perform the lengthening manoeuvre, which accounted for two-thirds of our failures.

Advantages over other lengthening techniques are said to be short operative time, negligible scarring, immediate weight bearing after surgery, and short immobilization time (Lee and Ko Citation2005). The popularity of this technique may be attributed to its simplicity. There have been surprisingly few published results, however, and most of these have focused on functional outcome. Tracy (Citation1976) described no complications with the triple hemisection technique as part of a more complex treatment in adult hemiplegia in 16 patients. Berg (Citation1992) reported 5 inadvertent complete tenotomies in 37 lengthenings, which healed during 2 months of cast immobilization. Cheng and So (Citation1993) reported 1 over-lengthening, no rupture, 4 recurrences, and an improvement in walking in ninetenths of cases after 71 lengthenings in 45 children with cerebral palsy at 2–5 years of follow-up. Katz et al. (Citation2000) performed 52 lengthenings in 36 children with cerebral palsy. They commented that there was “in some cases excessive release of the tendon during the sliding manipulation” and recurrence in one-fifth of the lengthenings after 5–10 years. For major corrections of equinus deformity, the hemisectioned parts of the Achilles tendon have to slide more, with greater risk of rupture. This was confirmed by Lee and Ko (Citation2005), who performed the triple hemisection technique during an open procedure in 25 ankles, and found a positive correlation between the length of gaps after the sliding procedure and the amount of correction, leading to one near-rupture. The distances between the hemisections were 3–5 cm, which is more than in the original description, and protects against total discontinuity of the sliding parts. These authors also described irregular sliding of the fibers in the gap.

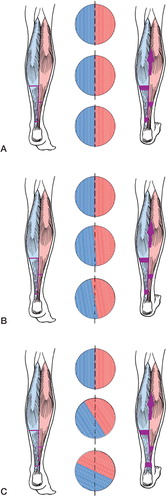

We performed the percutaneous procedure in 20 adult ankles from cadavers. These ankles did not have equinus deformities, and the total lengthening and increase in dorsal flexion was moderate, so this was a best-case scenario. Still, there was failure of one-third of all hemisections. There are several reasons for this high failure rate. Firstly, in adult patients—particularly when they are obese— the boundaries of the Achilles tendon are less well defined on palpation than in children. Secondly, sliding of the tendon after 3 simple hemisections will only occur when the tendon fibers are parallel in the sagittal axis. However, the fibers in the Achilles tendon are twisted like the fibers in a Manila rope. The angle of the twist varies from 11 to 65 degrees, according to Van Gils et al. (Citation1996). When the individual twist is minimal, the fibers are almost parallel sagittaly. When the twist is maximal, however, the 3 transverse hemisections will not sever neighboring fibers, and the sliding mechanism will fail or remain incomplete—as reflected by the irregular sliding of the fibers that was observed by Lee and Ko (Citation2005) (). Thirdly, when 1 hemisection does not slide, the other 2 will slide more to compensate, with the danger of (near-) rupture. This was observed in 3 of the tendons.

Figure 2. Artist’s impression of the triple-hemisection Achilles tendon lengthening with cross sections. A. 0° torsion (theoretical situation). The tendon fibers are parallel. 3 hemisections will sever neighboring fibers and the fiber bundles will glide along each other. B. 11° torsion. The tendon fibers are still almost parallel and the fibers will still glide along each other after 3 hemisections. C. 65° torsion. The 3 hemisections do not sever neighboring fibers, and the gliding mechanism will fail or remain incomplete.

Our observations using 20 legs from 10 cadavers cannot be considered as being completely independent. However, no pair of legs showed a similar failure pattern.

Our findings support our hypothesis that technical (rather than clinical) failures in the triple hemisection procedure may occur more often than has been acknowledged. The few studies mentioned previously that have been published suggest good results with the percutaneous technique when performed in children. However, to be certain of lengthening the tendon evenly by taking the twist of its fibers into account, we suggest that it be performed as an open procedure, especially in cases where the boundaries of the tendon are less easily palpable (adults, obese children). We agree with the suggestion of Lee and Ko (Citation2005) regarding use of the largest possible distance between the hemisections in order to reduce the risk of near- or complete rupture. During an open procedure, the lengthening process can be followed visually and incisional corrections can be made. We are considering a prospective randomized controlled trial to verify that there are no increased risks or disadvantages associated with the open procedure.

Eva Hoefnagels was supported by a grant from the POM Foundation. We appreciate the methodological help of Jonas Ranstam, statistics consultant.

Contributions of authors

EMH: performed the study and wrote the manuscript. MDW: assisted in the laboratory part and revised the manuscript. SMB: organized the study and revised the manuscript. BAS: designed the study and completed the manuscript.

- Berg E E. Percutaneous Achilles tendon lengthening complicated by inadvertent tenotomy. J Pediatr Orthop 1992; 12: 341–3

- Bleck E E. Orthopaedic management in cerebral palsy. J B Lippincott Co, Philadelphia 1987

- Cheng J C Y, So W S. Percutaneous elongation of the Achilles tendon in children with cerebral palsy. Int Orthop 1993; 17: 162–5

- Hatt R N, Lamphier T A. Triple hemisection: a simplified procedure for lengthening the Achilles tendon. N Engl J Med 1947; 236: 166–9

- Hoke M. An operation for the correction of extremely relaxed flat feet. J Bone Joint Surg 1931; 13: 773–83

- Katz K, Arbel N, Apter N, Soudry M. Early mobilization after sliding Achilles tendon lengthening in children with spastic cerebral palsy. Foot Ankle Int 2000; 21: 1011–4

- Lee W-C, Ko H-S. Achilles tendon lengthening by triple hemisection in adult. Foot Ankle Int 2005; 12: 1018–20

- Salamon M L, Pinney S J, Van Bergeyk A, Hazelwood S. Surgical anatomy and accuracy of percutaneous Achilles tendon lengthening. Foot Ankle Int 2006; 27: 411–3

- Tracy H W. Operative treatment of the plantar-flexed inverted foot in adult hemiplegia. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1976; 58: 1142–5

- Van Gils C C, Steed R H, Page J C. Torsion of the human Achilles tendon. J Foot Ankle Surg 1996; 35: 41–8

- White J W. Torsion of the Achilles tendon: its surgical significance. Arch Surg 1943; 46: 784–7