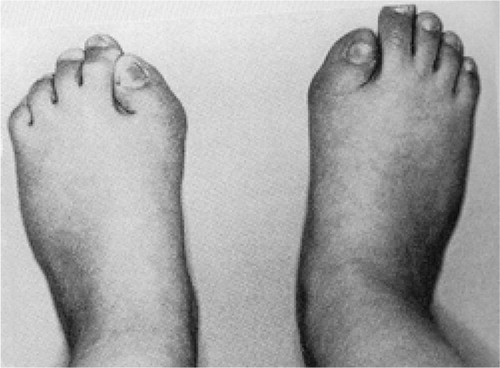

A 16-year‐old boy presented recently with classical symptoms and signs of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP). He had developed a swelling over his left scapula and posterior chest wall over a 2-week period (). The lesion was diffuse, firm, warm, and was not tender. The patient was well and blood investigations, including inflammatory markers, were normal. He had short first metatarsals similar in appearance to those shown in . MRI revealed a diffuse inflammatory, edematous mass involving the muscles of the back and postero‐lateral chest wall ( and ). A biopsy was performed, as the lesion was rapidly increasing in size. Histology showed no evidence of malignancy. FOP was diagnosed after consultation with the Scottish Bone Tumour Registry.

Discussion

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva occurs in approximately 1 in 2 million people (Connor Citation1996, Smith Citation1998). The origins of this condition in human history remain unknown. The biblical story of Lot's wife (Genesis 19: 1-26) may be referring to FOP (Kaplan Citation2005); however, the disease was first described by Patin in Citation1692.

Heterotopic ossification often progresses from early childhood, with patients becoming immobile and confined to a wheelchair by their twenties. Survival beyond the third decade is uncommon, as severe restriction of the chest wall results in cardiorespiratory demise. Recognition of the characteristic short first metatarsals in association with rapidly changing swellings of the neck or back in a child allows accurate diagnosis. The diagnosis of FOP is therefore clinical (Smith Citation1998). Understandably, malignancy is the most common misdiagnosis—with up to 1 in 3 cases being mistaken as cancer (Smith Citation1998, Magryta et al. Citation1999, Kitterman et al. Citation2005). Unnecessary biopsies are therefore often performed. In a study of 138 patients with FOP, 92 had a biopsy performed shortly after initial presentation (Kitterman et al. Citation2005). The soft tissue trauma caused by a biopsy can induce rapid ossification of the affected area.

Our case demonstrates the classical presentation and features of FOP in a relatively older patient, and highlights the common error of proceeding with biopsy in order to diagnose this rare condition.

There is no treatment for FOP (Kaplan Citation2005). The genetic mutation responsible has recently been identified, which gives new therapeutic hope for FOP patients but will also have important implications for other areas of bone biology. The mutation affects a bone morphogenic protein (BMP) receptor called activin receptor type IA (ACVR1) and has been mapped to chromosome 2q23-24 (Shore et al. Citation2006). BMPs are regulatory proteins that play a critical role in embryology, bone formation, and fracture healing (Chen et al. Citation2004). ACVR1 is an important signaling control protein in chondrocytes of the growth plate and cells of skeletal muscle. Enhanced activation of ACVR1 is seen in FOP (Shore et al. Citation2006). Our knowledge of this mutation will now provide a specific target for drug development and gene therapy (Kaplan et al. Citation2007). However, animal models must be developed to investigate the molecular mechanisms prior to the development of such therapies. In the future, other areas of orthopedics may benefit from this research. If the ACVR1 control mechanism can be manipulated, it may be possible to help patients who develop heterotopic ossification after hip surgery or after a head injury. It may also help in the treatment of patients where bone formation is lacking, such as nonunion of a fracture.

Contributions of authors

SWH: research, communication with Prof. FS Kaplan through the International Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva Association, and writing of the manuscript. CR: case study and review of the manuscript. PRR: supervision and review of the manuscript.

We are grateful to Prof. FS Kaplan and the International Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva Association for permission to publish the image in .

- Chen D, Zhao M, Mundy G R. Bone morphogenic proteins. Growth Factors 2004; 22(4)233–41

- Connor J M. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva - lessons from rare malides. N Engl J Med 1996; 335: 591–3

- Genesis. 19: 1–26, The Bible

- Kaplan F S. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. An historical perspective. Clin Rev Bone Min Metab 2005; 3(3–4)179–81

- Kaplan F S, Tabas J A, Gannon F H, Finkel G, Hahn G V, Zasloff M A. The histopathology of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: an endochondral process. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1993; 75: 220–30

- Kaplan F S, Shore E M, Glaser D L, Emerson S. The medical management of fibrodysplsia ossificans progressiva: Current treatment considerations. Clin Proc Intl Clin Consort FOP 2005; 1(3)1–71

- Kaplan F S, Glaser D L, Pignolo R J, Shore E M. A new era for fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: a druggable target for the second skeleton. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2007; 7(5)705–12

- Kitterman J A, Kantanie S, Rocke D M, Kaplan F S. Iatrogenic harm caused by diagnostic errors in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Pediatrics 2005; 116: 654–61

- Magryta C J, Kligora C J, Temple T H, Malik R K. Clinical presentation of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: Pitfalls in diagnosis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1999; 21(6)539–43

- Lettres Patin G, Guy Patin choisies de fev. M. Cologne. Piere du Laurens 1692; 1: 28–9

- Shore E M, Xu M, Feldman G J, Fenstermacher D A, Brown M A, Kaplan F S. A recurrent mutation in the BMP type I receptor ACVR1 causes inherited and sporadic fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Nature Genetics 2006; 38(5)525–7

- Smith R. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: clinical lessons from a rare disease. Clin Orthop 1998, 346: 7–13