Abstract

Background and purpose Intermittent claudication in diabetes mellitus is commonly associated with arterial disease but may occur without obvious signs of peripheral circulatory impairment. We investigated whether this could be due to chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS).

Patients and methods We report on 17 patients (3 men), mean age 39 (18–72) years, with diabetes mellitus—12 of which were type 1—and leg pain during walking (which was relieved at rest), without clinical signs of peripheral arterial disease. The duration of diabetes was 22 (1–41) years and 12 patients had peripheral neuropathy, retinopathy, or nephropathy. The leg muscles were tender and firm on palpation. Radiography, scintigraphy, and intramuscular pressure measurements were done during exercises to reproduce their symptoms.

Results 16 of the 17 patients were diagnosed as having CECS. The intramuscular pressures in leg compartments were statistically significantly higher in diabetics than in physically active non‐diabetics with CECS (p < 0.05). 15 of the 16 diabetics with CECS were treated with fasciotomy. At surgery, the fascia was whitish, thickened, and had a rubber‐like consistency. After 1 year, 9 patients rated themselves as excellent or good in 15 of the 18 treated compartments. The walking time until stop due to leg pain increased after surgery from less than 10 min to unlimited time in 8 of 9 patients who were followed up.

Interpretation Intermittent claudication in diabetics may be caused by CECS of the leg. The intramuscular pressures were considerably elevated in diabetics. One pathomechanism may be fascial thickening. The results after fasciotomy are good, and the increased pain‐free walking time is especially beneficial for diabetics.

Lower‐extremity complaints caused by neuropathy, angiopathy, or arteriosclerosis are frequent in diabetics (Dolan et al. Citation2002, Rathur and Bolton Citation2005). Neuropathic leg pain is rarely effort‐related and intermittent claudication in diabetics is often ascribed to vascular disease. Furthermore, diabetes mellitus is considered to be an independent risk factor for exertional leg pain (Wang et al. Citation2005). Thus, a proportion of diabetics have effort‐related leg pain without obvious signs of arterial disease.

Non‐vascular causes of exercise‐induced leg pain include spinal or inflammatory diseases and stress fractures. Another cause is chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS) of the leg, mainly described in running athletes. CECS is characterized by increased muscle compartment pressure during exertion, impaired tissue circulation, pain, and sometimes neurological deficits (Pedowitz et al. Citation1990, Mohler et al. Citation1997, Blackman Citation2000). The diagnosis is based on clinical history of leg pain during exercise and increased intramuscular pressure (Pedowitz et al. Citation1990). Anterior compartments of the leg are the most frequently affected, although other compartments may also be involved. Fasciotomy of the compartments that are involved leads to good outcome (Fronek et al. Citation1987, Styf Citation2004).

Occasional cases of compartment syndrome of the leg in diabetic patients have been reported, but these have been acute compartment syndromes due to muscle necrosis, requiring emergency surgery (Pamoukian et al. Citation2000, Jose et al. Citation2004).

Intermittent claudication is thus not always explained by arterial disease in diabetics. Does CECS of the leg exist in diabetes mellitus?

Patients and methods

When performing a clinical study of CECS of the leg, we unexpectedly found 4 diabetics with this disorder (Edmundsson et al. Citation2007). This prompted us to ask the diabetic clinic at Umeå University Hospital to send us all diabetics with activity‐related leg pain without clinical signs of circulatory insufficiency in order to explore our finding. During a 2‐year period, we got 13 additional diabetes patients. Thus, we had 17 diabetics with intermittent claudication but without clinical signs of distal circulatory impairment; they all had normal palpable foot pulses (Table). We performed plain radiography and scintigraphy of the leg to exclude bone or joint disorders causing pain.

Treadmill exercise was used to reproduce their symptoms, with increasing velocity over 10 min, and the velocity and slope of the treadmill were adjusted so that previous leg pain was reproduced. The diabetic patients with CECS reported increasing pain (usually rating 7 on the 10‐point Borg scale) in their leg(s) (compartments) and/or they rated exertion as “very heavy”—17 on the 20‐point Borg scale—at the end of the test (Borg Citation1973). Intramuscular pressure was monitored during microcapillary infusion with isotonic saline at a rate of 1.5 mL/hour, via a catheter (Myopress; Athos Medical, Höör, Sweden) connected to a pressure transducer (PMSET 2DT‐XO 2TBG; Becton Dickinson, Singapore). An ordinary Teflon cannula was inserted into the muscle belly with the patient in supine position. Using this cannula, the Myopress catheter was introduced into the muscle (to a depth of at least 15–20 mm beneath the fascia) (Styf and Körner Citation1986).

We measured both legs, starting with anterior muscle compartment pressure (and in 1 patient who did not improve in 6 months the posterior compartment was also decompressed). Local anesthetic was used only in the skin and fascia. The catheter was inserted either into the anterior tibial compartment of the leg about 10–15 cm below the fibula head, at an angle of 30 degrees to the skin, parallel to the tibia in the distal direction—and for 1 patient the deep posterior compartment, on the medial aspect of the middle of the leg. Measurements were done with the patient in supine position at rest, after 1, 5, 10, and 15 min. The patients were also asked to rate their pain at these intervals.

A diagnosis of CECS was made using the following criteria: (1) history of exercise‐induced pain/symptoms with reproduction of symptoms and pain during the exercise test, (2) intramuscular pressure at rest of > 15 mm Hg and/or intramuscular pressure of > 30 mm Hg 1–2 min after the end of the exercise test, and/or intramuscular pressure of > 20 mm Hg 5 min after the end of the exercise test together with the reproduced leg pain (Pedowitz et al. Citation1990).

The patients with CECS were recommended treatment with fasciotomy of the anterior tibial and peroneal compartments (Fronek et al. Citation1987, Styf Citation2004). By way of a 5‐cm skin incision halfway between the fibular shaft and the tibial crest in the mid‐portion of the leg, we made a subcutaneous dissection of the fascia as far as possible proximally and distally at the anterior and lateral compartments. Then we decompressed both compartments with a fasciotomy. In addition, we always removed a 1‐cm‐wide fascia strip when performing the procedure and used a suction drainage over‐night. Posterior compartments were treated with a fasciotomy of superficial soleus and gastrocnemius muscles and the deep posterior compartments (Styf Citation2004). Postoperatively, the patients used crutches for 3 days and were then allowed full weight bearing. They used a compression bandage for 3 weeks during wound healing to reduce postoperative edema.

To compare the preoperative intracompartmental pressure values of the diabetics with CECS, we used a group consisting of 18 physically active non‐diabetic individuals (the “overuse group”) with CECS (8 men, 10 women) and with a mean age of 29 (16–51) years, who were examined with the same pressure‐recording procedure (Edmundsson et al. Citation2007). In the “overuse group”, there were several patients with symptoms of CECS during walking. They had all been treated earlier with fasciotomy with excellent or good outcome, as previously reported (Edmundsson et al. Citation2007). The surgical outcome was evaluated according to Abramowitz et al. (Citation1994), including also a separate patient's rating of pre‐ and postoperative walking time before incapacitating leg pain (Table). The follow‐up time was more than 1 year. For comparisons between the groups, we used a non‐parametric test (Kruskal‐Wallis) with a rejection level of 5%.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Umeå University, Sweden.

Results

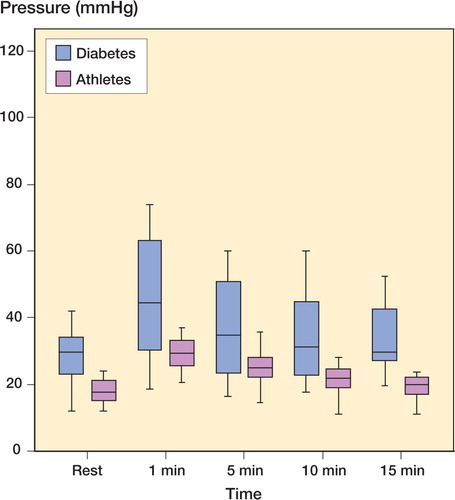

16 of the 17 referred diabetics with exercise‐induced leg pain had increased intramuscular pressure at rest and an even higher pressure after exercise, compatible with CECS (Table). The mean disease duration was 22 (1–1) years, and 12 patients had type 1 diabetes and 5 had type 2 diabetes. All had a typical history of intermittent claudication with a mean duration of 6 (0.2–15) years. The leg pain increased during walking so severely that they had to stop. The pain lasted for 10 min or longer, and was described as deep and constant with a feeling of tightness. The most striking finding on clinical examination was that the leg muscles were firm and tender on palpation even at rest. After 20 toe‐lifts, the patients experienced pain in the leg and the muscles were now even harder and more painful. The preoperative HbA1c levels indicated that the diabetes control had not been ideal. The diabetics had higher intramuscular pressure at all intervals compared to physically active non‐diabetics with CECS (Figure).

Muscle pressure (mm Hg) in the m tibialis anterius in non-diabetics (green) and diabetics (blue) with chronic compartment syndrome: at rest, immediately after provocation of leg pain by treadmill walking, and at intervals thereafter. The transverse lines show the median, boxes represent 50% of the observations, and whiskers represent 75% of the observations. Diabetes: n = 16 non-diabetics; n = 18. Differences between the groups at all times, except 5 min, were statistically significantly different (p < 0.05). It is obvious that the variation was much higher in diabetics, and some of them consistently had very high pressures.

15 of the 16 diabetic patients with CECS were treated with fasciotomy of the anterior and lateral compartments; 1 was also operated with posterior fasciotomy and 1 patient refused surgery. At surgery, the fascia seemed to be thickened about 2–3 times compared to a normal fascia, was whitish, and had a rubber‐like consistency. The muscle appeared macroscopically normal. 9(18 operated legs) of the 15 surgically treated patients were followed more than 1 year postoperatively, and rated their legs as excellent (4 legs), good (11 legs), or fair (3 legs). The walking time until the patient had to stop because of leg pain increased from 10 min to unlimited in 8/9 patients after surgery. 3 patients had postoperative complications, 1 with superficial peroneal nerve injury in the left leg (case 2) and 2 with superficial infections (cases 13 and 15) that healed with antibiotics. In 1 diabetic patient without CECS, we could not confirm any diagnosis.

A 39‐year‐old man (case 7) who had insulin‐treated diabetes mellitus for 27 years is illustrative. In recent years, the patient had experienced increasing anterior leg pain during exercise with a maximal walking distance of 200 meters. He was an outdoor man, but had to stop hunting and sell his dog. Vascular examination did not explain the symptoms, and he was treated with different kinds of physiotherapy and analgesics. Measurement of intracompartmental pressure during reproduction of symptoms gave high values, both at rest and after exercise. After surgical decompression, he walks without any restriction and has resumed hunting.

Discussion

CECS of the leg does occur in diabetes mellitus and gives symptoms similar to intermittent claudication of arterial genesis. This is a new differential diagnosis when evaluating diabetics with exertional pain in the leg. The physical signs are firm and tender leg muscles. The diagnosis is easily made by measurement of intramuscular pressure during reproduction of symptoms and signs. The results after fasciotomy in diabetics seem encouraging, and are equal to those in other categories of patients e.g. physically active non‐diabetics, although these groups of course have different functional levels (Edmundsson et al. Citation2007). The increased pain‐free walking time is especially beneficial to diabetics.

We diagnosed CECS of the leg in difficult‐to‐treat diabetic patients with long disease duration, and with accompanying diabetic complications in almost all cases. Only 1 of our patients had a short history of diabetes and the role of diabetes in the development of CECS may be questionable in this case. Since most patients had a long history and numerous other diabetes complications, it appears that the degree of severity and the duration of diabetes is important for the development of CECS. The intracompartmental pressures were remarkably high in diabetics, sometimes approaching impeding levels for perfusion. It is possible that a vascular adaptation together with the patient's limitation of physically activity because of pain reduces the risk, since spontaneous muscle necrosis has only been reported occasionally in diabetics (Pamoukian et al. Citation2000, Jose et al. Citation2004). One proposed explanation for diabetic neuropathy is the double-crush syndrome, i.e. that blood supply to the nerves is simultaneously hurt by endoneural swelling and local compression in narrow anatomical spaces (Dellon and Mc Kinnon Citation1991). The considerably high intramuscular pressures in our diabetics add another compressive force to these nerves.

The cause of the high intracompartmental pressure in diabetics is unclear, and may be explained by soft tissue changes or perfusion changes, or both. The striking finding of a thickened fascia makes it tempting to assume that a reduced volume and reduced compliance of the muscle compartment is one pathological mechanism. Angiopathy and neuropathy may certainly have roles to play, and these 3 factors probably cooperate with each other. The cause of the thickened fascia may be non-enzymatic glycosylation of collagen, resulting in the connective tissue changes previously described in diabetes mellitus, e.g. stiff-joint syndrome (Smith et al. Citation2003).

Our patients were treated with anterior fasciotomy, but if the disorder is caused by general soft tissue alterations other compartments of the legs (such as the posterior compartment) may also be affected. The CECS of the anterior compartment gives symptoms more easily since the blood supply to this compartment is the most vulnerable one (Styf Citation2004). Consequently, the symptoms from a posterior compartment syndrome appear more insidious and may perhaps be more easily diagnosed clinically later on after treating anterior compartment syndrome. One of our patients showed increased compartment pressure in the posterior compartment also, and was treated with posterior fasciotomy. It seems likely that more cases like this will emerge in the future.

Limited peripheral nerve decompression has previously been reported to be beneficial in diabetics (Wood and Wood Citation2003). Perhaps some of the patients treated with local nerve decompression also had CECS, and not only local nerve entrapment.

Why has CECS not been recognized in diabetics before? In the first place, diagnosis of CECS seems to be rather unknown for physicians treating diabetes mellitus patients and it has mostly been associated with healthy young athletes, not with people with a sedentary lifestyle or other diseases. Secondly, the focus in diabetics with leg pain has been on arterial disease or neuropathy. Thirdly, the progress of intermittent claudication due to CECS seems to be slow since most of our cases had experienced symptoms for years—and perhaps patients adapt to low functional level.

One limitation of this study is that few patients were included, and these were only partly analyzed retrospectively since we did not at first realize that diabetes might be a pathomechanism. Thus, circulatory evaluation was not done in a consistent way. We are currently performing an extended study.

It remains to be seen what role CECS plays in total leg morbidity in diabetes mellitus, but if a patient has incapacitating exercise-induced leg pain with increased intracompartmental pressure, decompression of the compartments involved should be considered.

Contributions of authors

DE and GT formulated the research hypothesis. DE performed surgery, made the measurements, and performed clinical examinations. DE, GT, and OS jointly did the analyses and wrote the paper.

- Abramowitz A J, Schepsis A A. Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome of the Lower Leg. Orthop Rev 1994; 3: 219–26

- Blackman P G. A review of chronic exertional compartment syndrome in the lower leg. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000; 32: S4–S10

- Borg G A V. Perceived exertion: a note on “history” and methods. Med Sci Sports 1973; 5: 90–3

- Dellon A L, Mc Kinnon S E. Chronic nerve compression for the double-crush hypothesis. Ann Plast Surg 1991; 26: 259–64

- Dolan N C, Liu K, Criqui M H, Greenland P, Guralnic J M, Chan C, Schneider J R, Mandapat A L, Martin G, Mc Dermott M M. Peripheral artery disease, diabetes, and reduced lower extremity functioning. Diabetes Care 2002; 25: 113–20

- Edmundsson D, Toolanen G, Sojka P. Chronic compartment syndrome also affects non-athletic subjects: A prospective study of 63 cases with exercise-induced lower leg pain. Acta Orthop 2007; 78: 136–42

- Fronek J, Mubarak S J, Hargens A R, Lee Y F, Gershuni D H, Garfin S R, Akeson W H. Management of Chronic Exertional Anterior Compartment Syndrome of the Lower Extremity. Clin Orthop 1987, 220: 217–27

- Jose R M, Viswanathan N, Aldlyami E, Wilson Y, Moiemen N, Thomas R. A spontaneous compartment syndrome in a patient with diabetes. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2004; 86: 1068–70

- Mohler L R, Styf J, Pedowitz R A, Hargens A R, Gershuni D H. Intramuscular deoxygenation during exercise in patients who have chronic anterior compartment syndrome of the leg. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1997; 79: 844–8

- Pamoukian V N, Rubino F, Iraci J C. Review and case report of idiopathic lower extremity compartment syndrome and its treatment in diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab 2000; 26: 489–92

- Pedowitz R A, Hargens A R, Mubarak S J, Gershuni D H. Modified criteria for the objective diagnosis of chronic compartment syndrome of the lower leg. Am J Sports Med 1990; 18: 35–40

- Rathur H M, Bolton A J M. Recent advances in the diagnosis and management of diabetes neuropathy. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2005; 87: 1605–10

- Smith L L, Burnet S P, McNeil J D. Musculoskeletal manifestations of diabetes mellitus. Br J Sports Med 2003; 37: 30–5

- Styf J. Compartment syndromes diagnosis, Treatment and complications. CRC Press 2004; 178–9

- Styf J, Körner L M. Chronic anterior-compartment syndrome of the leg. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1986; 68: 1338–47

- Wang J C, Criqui M H, Denenberg J O, Mc Dermott M M, Golomb B A, Fronek A. Exertional leg pain in patients with and without peripheral arterial disease. Circulation 2005; 112: 3501–8

- Wood W A, Wood M A. Decompression of Peripheral Nerves for Diabetic Neuropathy in the Lower Extremity. J Foot Ankle Surg 2003; 42(5)268–75