Abstract

Background and purpose — Supracondylar humerus fractures are the most common type of elbow fracture in children. A small proportion of them are flexion-type fractures. We analyzed their current incidence, injury history, clinical and radiographic findings, treatment, and outcomes.

Patients and methods — We performed a population-based study, including all children <16 years of age. Radiographs were re-analyzed to include only flexion-type supracondylar fractures. Medical records were reviewed and outcomes were evaluated at a mean of 9 years after the injury. In addition, we performed a systematic literature review of all papers published on the topic since 1990 and compared the results with the findings of the current study.

Results — During the study period, the rate of flexion-type fractures was 1.2% (7 out of 606 supracondylar humeral fractures). The mean annual incidence was 0.8 per 105. 4 fractures were multidirectionally unstable, according to the Gartland-Wilkins classification. All but 1 were operatively treated. Reduced range of motion, changed carrying angle, and ulnar nerve irritation were the most frequent short-term complications. Finally, in the long-term follow-up, mean carrying angle was 50% more in injured elbows (21°) than in uninjured elbows (14°). 4 patients of the 7 achieved a satisfactory long-term outcome according to Flynn’s criteria.

Interpretation — Supracondylar humeral flexion-type fractures are rare. They are usually severe injuries, often resulting in short-term and long-term complications regardless of the original surgical fixation used.

Supracondylar extension-type humerus fractures are the most common fractures of the elbow in children, comprising up to 70% of all elbow fractures (Landin and Danielsson Citation1986). The incidence of supracondylar humerus fractures increases in the first 5 years of life, and peaks between the ages of 5 and 8 (Alburger et al. Citation1992). Thereafter, the incidence decreases until the age of 15, when the nature of the fracture is more like that in adults (Marquis et al. Citation2008). Older children often have greater displacement in their fracture pattern. Although these fractures have previously been considered to be more common in boys, recent studies have shown that there is an even distribution between sexes (Farnsworth et al. Citation1998, Houshian et al. Citation2001).

1–11% of the supracondylar fractures are of flexion-type (Fowles and Kassab Citation1974, Williamson and Cole Citation1991, Farnsworth et al. Citation1998, Cheng et al. Citation2001). They are more severe injuries, often requiring open reduction and resulting in a higher rate of neurovascular complications than extension-type fractures (Wilkins Citation1990). However, because of their rarity, only a few case series have been reported. Flexion-type fractures are poorly described—even in the pediatric orthopedic textbooks—and there is a lack of evidence regarding the best treatment (Mahan et al. Citation2007).

We assessed the frequency of flexion-type supracondylar humerus fractures in children <16 years of age during the last decade (2000–2009) in a defined geographical area. We also studied injury mechanisms, physical findings, treatment, and the short-term and long-term outcomes of these fractures. In addition to reporting our own experience, we have reviewed previous studies on flexion-type supracondylar humerus fractures performed during the modern fracture-treatment era (since 1990).

Patients and methods

All children in the geographic catchment area of Oulu University Hospital who were <16 years of age and had an anteriorly displaced (flexion-type) supracondylar humerus fracture during the period 2000–2009 were included in the study. Both operatively and non-operatively treated patients were included. The institution is the only unit treating childrens’ fractures in the area. The annual population of children in the area changed (between 84,820 and 86,385). 833 children had a distal humerus fracture (code S42.4 in the International Classification of Diseases, ICD, version 10). We systematically reviewed all the original radiographs in order to recognize and differentiate flexion-type supracondylar fractures from other elbow fractures. 606 supracondylar fractures were found, and 7 of them were flexion-type fractures. Injury history, clinical findings, radiographs, and treatment were reviewed for the study.

Lateral and posterior-anterior (PA) radiographs, available for all the children and taken upon admission, were used for classification. The flexion-type fractures were recognized according to anterior displacement or angulation of the distal fragment of the humerus in the lateral radiograph. All fractures were classified according to their severity, using modified Gartland-Wilkins and Pironi classifications (Pirone et al. Citation1988, Wilkins Citation1990). According to Gartland-Wilkins, type-I fractures show no displacement, type-II fractures show moderate displacement while the anterior bone cortex is intact (Mahan et al. Citation2007), and type-III fractures have severe displacement with hardly any cortical contact left. Type-IV fractures include multidirectionally unstable fractures (Leitch et al. Citation2006).

Pirone classification type-I includes non-displaced fractures. Type-IIA includes non-displaced but angulated fractures, and type-IIB includes partially displaced fractures. Type-III fractures are completely displaced. The dislocation of the distal fragment can be any of the following: anterolateral, anteromedial, or anterior (Pirone et al. Citation1988).

Long-term outcome of flexion-type fractures was determined at a follow-up visit at a mean interval of 9 (5–11) years after the injury. Carrying angle and range of motion were measured clinically with a goniometer. Stability of the elbows was determined (with posterolateral and varus-valgus stress tests). A hydraulic Jamar dynamometer was used to determine grip strength, with the best of 3 attempts being recorded. Flynn’s criteria for elbow assessment were used to classify the overall recovery as being satisfactory (excellent or good) or unsatisfactory (fair or poor) (Flynn et al. Citation1974). Furthermore, the Mayo elbow performance score (MEPS) and the disability of arm, shoulder, and hand (DASH) score were determined for all patients (Hudak et al. Citation1996, Cusick et al. Citation2014).

The systematic literature search was performed in PubMed, Medline, and Google Scholar for studies published from 1990 to July 2015, evaluating the flexion-type fractures in children. Dunlop’s traction used to be the main treatment method (Vahvanen and Aalto Citation1978), but since the 1990s, other treatments have become more popular. The keywords and “medical subject headings” terms used were “supracondylar fracture”, “anterior*”, “flexion”, “humerus”, “pediatric”, and “children”. Furthermore, the references of all the articles identified were examined for additional relevant reports. All articles were considered regardless of language, in case an abstract in English was available.

Ethics

The Ethics Committee Board of Vaasa Central Hospital evaluated and approved the study plan in advance (2008-05-26). The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1983.

Results

Of 606 supracondylar fractures in the area during the period 2000–2009, there were 7 flexion-type fractures (1.2%). The mean annual incidence was 0.8 per 105 children.

Patient characteristics

Of the 7 fractures, 5 were in boys. The mean age was 10 (6–14) years. The injury mechanism was a simple falling on the same plane in 3 children, a trampoline accident (n = 1), a playground injury (n = 1), wrestling (n = 1), and a traffic accident (n = 1). All fractures were closed. One child suffered from ulnar nerve symptoms and 3 children had unspecific sensory tingling ().

Table 1. The characteristics of the 7 patients with a flexion-type supracondylar humerus fracture

Radiographic classification

4 fractures were classified as multidirectionally unstable type-IV according to Gartland-Wilkins. 1 fracture was Gartland-Wilkins type-I, 1 was type-II, and 1 was type-III. 5 were Pironi IIA–IIB fractures and 2 were Pironi III fractures ().

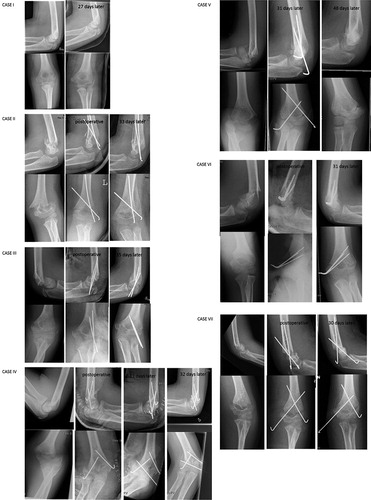

Figure 1. The primary radiographs (anterior-posterior and lateral projection) of all flexion-type supracondylar humerus fractures (cases I–VII) during the 10 years of the study period (2000–2009). Postoperative radiographs and the radiographs at the last short-term follow-up visit are also presented.

Treatment

All but 1 of the fractures were operated on. Closed reduction and percutaneous pinning (CRPP) with Kirschner wires was used in 2 cases with type-IV fracture and in 1 case with a type-III fracture. Open reduction and internal (pin) fixation (ORIF) was performed for 1 type-II and 2 type-IV fractures. The Gartland-Wilkins type-I fracture was treated by casting ().

Short-term outcome

4 children suffered from short-term complications within 12 months. The non-displaced type-I fracture initially resulted in reduced range of motion, but it improved later. The type-II fracture healed satisfactorily without significant complications. The type-III fracture was complicated by ulnar nerve symptoms, but it recovered during the following year. 2 type-IV fractures had a satisfactory outcome at the end of the short-term follow-up. 1 type-IV fracture resulted in a slight decrease in flexion and residual valgus deformity, while another case with a type-IV fracture suffered from a 60-degree decrease in extension range despite further treatment ().

Long-term outcome

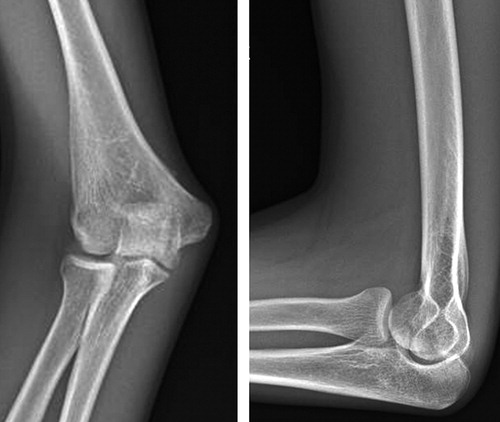

Range of motion or grip strength was not reduced in the injured elbows in the long term, compared to the uninjured elbows (). In turn, carrying angle was 50% higher (from 14° in valgus to 21° in valgus) at the long-term follow-up (). 3 patients of the 7 had an unsatisfactory long-term outcome according to Flynn’s criteria (). They were all originally Gartland-Wilkins grade-IV fractures. 2 of 3 children who were operated on with open reduction had an unsatisfactory Flynn scoring whereas 2 of 3 children who had closed reduction had satisfactory outcomes. Casting in situ resulted in good long-term outcome in 1 child. The mean DASH score was 4.8 (0–31.6) (). The mean MEPS was 94 points and 6 of the children had >85 points.

Figure 2. A radiographic investigation (antero-posterior and lateral projections) of the elbow showing an increased carrying angle 9 years after the injury. The patient (case IV) was 14 years old when he sustained a Gartland-Wilkins type-IV supracondylar humerus fracture.

Table 2. Long-term clinical recovery of flexion-type supracondylar humerus fractures mean 9 (5–11) years after the injury

Table 3. Outcome measurements for the patients with a former flexion-type supracondylar humerus fracture mean 9 years after the injury

Flexion-type supracondylar humerus fractures in the literature

We found 5 previous studies involving flexion-type supracondylar humerus fractures published since 1990 (Williamson and Cole Citation1991, De Boeck Citation2001, Garg et al. Citation2007, Mahan et al. Citation2007, Khare Citation2010). The total number of children with a flexion-type supracondylar humerus fracture in the literature searched was 137 (73 boys). The mean age of the patients was 7 (6–8). 49% of the fractures were of type-III (type-IV was not separately reported), 40% were type-II and 11% were type-I. Two-thirds were treated by closed reduction and pinning with a Kirschner wire while the others were treated by casting or open reduction with pinning. 2 studies gave medium-term or long-term results: Nine-tenths of the children reached excellent or good outcomes at a mean of 6 years after the injury, according to De Boeck (Citation2001). Garg et al. (Citation2007) reported that 11 of 14 children achieved satisfactory results at medium-term follow-up (1–3 years) ().

Table 4. Patient demographics, fracture classification, and treatment of flexion-type supracondylar fractures in children according to the current study and the literature available since 1990

Discussion

The rate of flexion-type fractures in the present study was even lower than previously reported by many authors, which is usually around 2% (Kasser and Beaty Citation2006, Mahan et al. Citation2007). However, many previous reports were based only on patients treated in hospital; they lacked the population-based study setting that we used, which may have resulted in a higher occurrence of more severe flexion-type fractures.

Simple falling was the most common cause of flexion-type fractures in our study. This is in line with the literature: falling on the point of the elbow, landing on the outstretched hand, or landing with arms twisted behind the back. This results in failure of the posterior cortex and anterior dislocation of the distal fragment.

The mean age of the children in the present study was 10 years. This is higher than what has been previously reported: Garg et al. (Citation2007) reported 14 flexion-type fractures in 10 boys and 4 girls with a mean age of 6.4 years. Khare (Citation2010) reported a mean age of 6.4 years in their series of 22 children (). Flexion-type fractures appear to be more common in older children than extension-type fractures, which are usually seen in children around 5–7 years of age (Omid et al. Citation2008). The reason for this difference is unclear.

Most of the fractures in this series were severe, and at least partially displaced according to Gartland-Wilkins. This is in line with the study by Mahan et al. (Citation2007) (). Non-displaced fractures (1 of 7 in our series) are uncommon among flexion-type fractures. Displacement may be one reason for complications (Fowles and Kassab Citation1974, Wilkins et al. Citation1996).

The treatment of flexion-type fractures is controversial. Some authors have stated that even displaced flexion-type fractures could be managed by closed reduction and casting, whereas some others have suggested that percutaneous pinning is essential for type-II and type-III fractures in order to maintain proper reduction (Williamson and Cole Citation1991, De Boeck Citation2001). In our series, just 1 patient was treated with cast immobilization, while surgical stabilization was performed for 6 others. Adequate reduction and pin placement are essential to avoid re-displacement, secondary displacement, late deformity, and iatrogenic nerve injuries (Wilkins et al. Citation1996). 3 fractures were stabilized via lateral entry point, and 1 of them (case V) lost reduction in the follow-up. 3 of 6 fractures required open reduction. The high rate of open surgery is in line with the most recent report (Mahan et al. Citation2007).

4 of the 7 patients suffered short-term complications during follow-up. Reduced range of motion, changed carrying angle, and ulnar nerve irritation were the most frequent complications. Generally, a higher rate of growth disturbances and other complications is seen in flexion-type fractures compared to most other fractures in children (Marquis et al. Citation2008, Miranda et al. Citation2014).

We found that 3 of the 7 patients with flexion-type supracondylar humerus fractures had an unsatisfactory long-term outcome according to Flynn’s criteria. Change in carrying angle was the major long-term complication. The rate of poor outcomes was higher than previously reported by De Boeck and by Garg et al. However, the follow-up time was 6 years and 3 years, respectively, in these studies, as compared to 9 years in the present study. Sequelae of flexion-type supracondylar humerus fractures may change over several years until growth plate closure. Despite the low Flynn scores, MEPS was high in most patients (mean: 94 of 100 points). Moreover, just 1 patient showed a decrease greater than the minimal clinically important difference (MCID; 15 points) in MEPS (de Boer et al. Citation2001). The mean DASH score was 4.8 points, showing just slight disability in daily activities.

EK: data collection and writing of the manuscript, RP study design and preparation of the manuscript, TP statistical consultation and manuscript preparation, MS data collection and manuscript preparation, WS study concept and design, manuscript revision, supervision, JJS study concept and design, follow-up clinical investigations, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript writing and revision, supervision.

This study was supported by Alma and K.A. Snellman foundation, Vaasa Foundation of Physicians, The Finnish Medical Foundation, The Emil Aaltonen Foundation, Finska Läkaresällskapet and the Medical Society of Finland.

No competing interests declared.

- Alburger P D, Weidner P L, Betz R R. Supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1992; 12 (1): 16–19.

- Cheng J C, Lam T P, Maffulli N. Epidemiological features of supracondylar fractures of the humerus in chinese children. J Pediatr Orthop B 2001; 10 (1): 63–7.

- Cusick M C, Bonnaig N S, Azar F M, Mauck B M, Smith R A, Throckmorton T W. Accuracy and reliability of the mayo elbow performance score. J Hand Surg 2014; 39 (6): 1146–50.

- De Boeck H. Flexion-type supracondylar elbow fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2001; 21 (4): 460–3.

- de Boer Y A, Hazes J M, Winia P C, Brand R, Rozing P M. Comparative responsiveness of four elbow scoring instruments in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2001; 28 (12): 2616–23.

- Farnsworth C L, Silva P D, Mubarak S J. Etiology of supracondylar humerus fractures. J Pediatr Orthop 1998; 18 (1): 38–42.

- Flynn J C, Matthews J G, Benoit R L. Blind pinning of displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. sixteen years’ experience with long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1974; 56 (2): 263–72.

- Fowles J, Kassab M. Displaced supracondylar fractures of the elbow in children. A report on the fixation of extension and flexion fractures by two lateral percutaneous pins. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1974; 56 (3): 490–500.

- Garg B, Pankaj A, Malhotra R, Bhan S. Treatment of flexion-type supracondylar humeral fracture in children. J Orthop Surg 2007; 15 (2)

- Houshian S, Mehdi B, Larsen M S. The epidemiology of elbow fracture in children: Analysis of 355 fractures, with special reference to supracondylar humerus fractures. J Orthop Science 2001; 6 (4): 312–5.

- Hudak P L, Amadio P C, Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: The DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand) [corrected]. the upper extremity collaborative group (UECG). Am J Ind Med 1996; 29 (6): 602–8.

- Kasser J R, Beaty J H. Supracondylar fractures of the distal humerus. Rockwood and Wilkins’ Fractures in Children.6th Ed.Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins 2006; pp: 543–89.

- Khare G N. Anteriorly displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus are caused by lateral rotation injury and posteriorly displaced by medial rotation injury: A new hypothesis. J Pediatr Orthop B 2010; 19 (5): 454–8.

- Landin L A, Danielsson L G. Elbow fractures in children: An epidemiological analysis of 589 cases. Acta Orthop 1986; 57 (4): 309–12.

- Leitch K K, Kay R M, Femino J D, Tolo V T, Storer S K, Skaggs D L. Treatment of multidirectionally unstable supracondylar humeral fractures in children. A modified gartland type-IV fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88 (5): 980–5.

- Mahan S T, May C D, Kocher M S. Operative management of displaced flexion supracondylar humerus fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2007; 27 (5): 551–6.

- Marquis C P, Cheung G, Dwyer J S M, Emery D F G. Supracondylar fractures of the humerus. Current Orthop 2008; 22 (1): 62–9.

- Miranda I, Sanchez-Arteaga P, Marrachelli V G, Miranda F J, Salom M. Orthopedic versus surgical treatment of gartland type II supracondylar humerus fracture in children. J Pediatr Orthop B 2014; 23 (1): 93–9.

- Omid R, Choi P D, Skaggs D L. Supracondylar humeral fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008; 90 (5): 1121–32.

- Pirone A M, Graham H K, Krajbich J I. Management of displaced extension-type supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1988; 70 (5): 641–50.

- Vahvanen V, Aalto K. Supracondylar fracture of the humerus in children. A long-term follow-up study of 107 cases. Acta Orthop Scand 1978; 49 (3): 225–33.

- Wilkins K, Beaty J, Chambers H, Toniolo R. Fractures and dislocations of the elbow region. Fractures in children, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven 1996; pp: 653–887.

- Wilkins K E. The operative management of supracondylar fractures. Orthop Clin North Am 1990; 21 (2): 269–89.

- Williamson D, Cole W. Flexion supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children: Treatment by manipulation and extension cast. Injury 1991; 22 (6): 451–5.