Abstract

Background and purpose — Bisphosphonates are widely used in the treatment of bone loss, but they might also have positive effects on osteoblastic cells and bone formation. We evaluated the effect of in vivo zoledronic acid (ZA) treatment and possible concomitant effects of ZA and fracture on the ex vivo osteogenic capacity of rat mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs).

Methods — A closed femoral fracture model was used in adult female rats and ZA was administered as a single bolus or as weekly doses up to 8 weeks. Bone marrow MSCs were isolated and cultured for in vitro analyses. Fracture healing was evaluated by radiography, micro-computed tomography (μCT), and histology.

Results — Both bolus and weekly ZA increased fracture-site bone mineral content and volume. MSCs from weekly ZA-treated animals showed increased ex vivo proliferative capacity, while no substantial effect on osteoblastic differentiation was observed. Fracture itself did not have any substantial effect on cell proliferation or differentiation at 8 weeks. Serum biochemical markers showed higher levels of bone formation in animals with fracture than in intact animals, while no difference in bone resorption was observed. Interestingly, ex vivo osteoblastic differentiation of MSCs was found to correlate with in vivo serum bone markers.

Interpretation — Our data show that in vivo zoledronic acid treatment can influence ex vivo proliferation of MSCs, indicating that bisphosphonates can have sustainable effects on cells of the osteoblastic lineage. Further research is needed to investigate the mechanisms.

Bisphosphonates (BPs) are potent inhibitors of bone resorption and osteoclasts are the primary target (Fleisch Citation2000, Rogers Citation2003). Several studies have nevertheless found an osteogenic response when mature osteoblasts are continuously treated with BPs in vitro (Reinholz et al. Citation2000, Fromigué and Body Citation2002, Im et al. Citation2004, Pan et al. Citation2004). Giuliani et al. (Citation1998) injected young female mice with alendronate and etidronate and then isolated and cultured bone marrow (BM) cells ex vivo. Interestingly, they found mild but positive effects on the formation of alkaline phosphatase- (ALP-) positive colonies, indicating a proliferative and/or osteogenic effect in vivo. Li et al. (Citation1999, Citation2000) found that continuous incadronate treatment led to larger callus formation and delayed callus remodeling in an endochondral rat femoral fracture model. Using the same experimental model, McDonald et al. (Citation2008) showed that zoledronic acid (ZA) treatment led to increased hard callus bone mineral content (BMC), increased bone volume (BV), and increased callus strength.

Our previous study evaluating the effect of adjunct ZA treatment on bioactive incorporation in a rat medullary ablation model showed that continuous ZA treatment alone resulted in an intense trabecular bone accumulation during the 9-week follow-up period (Välimäki et al. Citation2006). Our preliminary analyses on BM mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) harvested from the ZA-treated rats indicated that ZA—in doses that were comparable to a clinical dose—could enhance the osteogenesis of MSCs (unpublished data). The current study was carried out to investigate possible effects of ZA on MSCs by determining whether ZA treatment in vivo affects proliferation and differentiation of MSCs ex vivo. We hypothesized that ZA would enhance proliferation and osteoblastic differentiation of MSCs, and we also investigated whether this effect would be more evident in the presence of fracture.

Methods

Animals, randomization, and experimental groups

The study protocol was approved by the National Animal Experiment Board (#ESHL-2009-08666/Ym23). 50 female Harlan Sprague-Dawley rats (mean age 19 (16–23) weeks and weight 286 (224–351) g) were obtained for the study, which was planned and executed according to the 3Rs of humane animal research. 31 animals were initially operated, but 2 were excluded because of non-mid-diaphyseal or comminuted fracture, and 2 because of failed fracture fixation during follow-up. 19 animals remained intact. Primary MSC cultures from 6 animals were lost due to contamination. Thus, altogether 40 animals completed the study.

Animals were first randomized to the fracture group or the intact group. 1 week after fracture surgery, they were randomized to weekly ZA, bolus ZA, or placebo. The 6 experimental groups were: intact with weekly placebo (I-P, n = 6); intact with bolus ZA (I-Z-B, n = 6); intact with weekly ZA (I-Z-W, n = 6); fracture with weekly placebo (F-P, n = 8); fracture with bolus ZA (F-Z-B, n = 7); and fracture with weekly ZA (F-Z-W, n = 7)

Fracture surgery and digital radiography

The animals were anesthetized with intramuscular administration of ketamine hydrochloride and medetomidine. Using standard sterile surgical techniques, a small incision was made anterior to the patella of the right distal femur. The patella was moved laterally to reveal the distal femoral condyles, and a 1.0-mm Kirschner wire was inserted into the medullary canal. A transverse mid-diaphyseal closed femoral fracture was induced using a drop-weight fracture apparatus (Hiltunen et al. Citation1993), which was designed according to Bonnarens and Einhorn (Citation1984). For postoperative pain relief, buprenorphine (0.01 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously twice a day for 3 days. The location and quality of each fracture was evaluated using the Faxitron digital radiography system (MX-20; Faxitron X-ray Corporation, Wheeling, IL) and Faxitron Imaging Software (Qados; Cross Technologies plc, Berkshire, UK). All the animals underwent imaging at 0, 4, and 8 weeks. They were maintained on regular chow and water in 1,029 cm2 cages (2–3 animals/cage, 21 °C ± 2 °C, 55 ± 15 relative humidity) with a 12-h light/dark cycle throughout the study. Animal welfare was monitored on a daily basis.

Zoledronic acid and placebo administration

Starting 1 week after fracture, ZA (Novartis Pharma) was administered subcutaneously as a single bolus of 0.1 mg/kg or as 7 weekly doses of 0.014 mg/kg, resulting in the same total dose of 0.1 mg/kg. This was comparable to the annual dose of 5 mg used clinically in treatment of patients with osteoporosis. Animals on placebo treatment received weekly subcutaneous injections of saline at 2 mL/kg.

Sample preparation and histology

8 weeks after fracture, all the animals were anesthetized. Blood samples were drawn by cardiac puncture and serum was collected. After that, the animals were killed using CO2. Both femurs and tibias were harvested. The left femur and left tibia were quickly cleaned in 70% ethanol and immediately transferred to cell culture facilities. Right femurs (intact or fractured) were radiographed, fixed in 10% formalin, and stored in 70% ethanol until micro-computed tomography (μCT) analysis was completed. After μCT, right femurs were decalcified (in 14% EDTA), followed by dehydration and embedding in paraffin. 5-μm tissue sections were stained with Weigert’s hematoxylin, Alcian blue, and van Gieson.

Micro-computed tomography

Fractured and intact femurs were scanned with μCT (SkyScan 1072). Specimens were rotated 180°, obtaining an image every 0.45° at 14.65-μm resolution. 3D analysis from a standardized 15-mm mid-diaphyseal segment comprising the fracture was performed with CTAn software (SkyScan) using calibration with 2 phantoms (250 and 750 mg/cm3) provided by the manufacturer (Salmon Citation2005). Bone mineral density (BMD), bone mineral content (BMC), and bone volume (BV) of healing and intact bone were measured by fitting Gaussian curves to grayscale histograms using Origin software (Origin Lab Corp., Northampton, MA). This method was also used to calculate global threshold values, to segment data sets for 3D reconstructions.

Bone marrow cell isolation and MSC cultures

In a laminar-flow cabinet, epiphyses were cut and bone marrow (BM) flushed out using basal medium (α-MEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics). Bones from each animal were processed separately. Cells were centrifuged, passed through a 22-G needle, plated at 106 cells/cm2, and cultured in basal medium. After 48 h, non-adherent cells were removed by rinsing twice with PBS and fresh basal medium containing 10−8 M dexamethasone (from here on referred to as MSC medium) was added. Half of the medium was changed on day 6. After 8–9 days, plastic adherent MSCs (passage 0) were trypsinized and counted before re-plating.

Osteoblast differentiation cultures and analysis

For osteogenesis, passage-0 cells were plated at 5,000 cells/cm2 in 24-well plates and cultured either in MSC medium or in osteoblast induction medium (MSC medium with 10 mM β-glycerophosphate and 70 μg/mL ascorbic acid; from here on referred to as OB medium). Half of the medium was replaced every 3–4 days. Osteoblastic differentiation was evaluated after 2 weeks of induction culturing by staining for ALP and von Kossa and by measuring alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity (Heino et al. Citation2004). For each read-out method, osteogenic induction was performed in 4 replicate wells per sample and 2 wells per sample served as control (MSC medium). Stained areas were quantified using automated image analysis (Alm et al. Citation2012).

Analysis of proliferative capacity and population doubling

Passage-0 MSCs were expanded at 5,000 cells/cm2 in basal medium up to passage 7 (at 9–10 weeks). Half of the medium was replaced every 3–4 days, and the cells were monitored and trypsinized when subconfluent for further passaging. Population doublings (PDs) at each passage were determined using the formula log(N)/log(2), where N is the number of cells at harvest divided by the number of cells plated. The cumulative PDs through passages 0–7, the maximum PDs and total PDs reached throughout passage 7, and the population doubling time (PDT) in days were analyzed.

Biochemical markers of bone metabolism

C-terminal crosslinked telopeptides of type-I collagen (CTX) as a resorption marker and N-terminal propeptides of type-I collagen (PINP) as a formation marker were measured in the serum samples obtained at killing, using RatLaps EIA and Rat/Mouse PINP EIA, respectively (both from IDS Nordic A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Statistics

To examine the effects of ZA, independently of fracture, pairwise comparisons between the intact groups and the fractured groups were performed separately using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test. The effects of fracture on the different parameters were examined by comparing each fracture group with its corresponding intact group using Student’s t-test. In cases where data were not normally distributed or had unequal variances, analyses were performed with the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by pairwise Mann-Whitney U-test. For evaluation of osteogenic differentiation of MSCs from different treatment groups, mixed-models ANOVA was used, with treatment group as fixed factor and rat identification number as random factor, to allow for multiple replicates from each individual rat. In the mixed-models analysis, restricted maximum likelihood (REML) was used as the method for estimations, and pairwise comparisons of the estimated marginal means was performed using the Sidak’s test option. The intact groups and the fracture groups were analyzed separately, with pairwise comparisons performed between the 3 subgroups (P, Z-B, and Z-W). These data are presented as estimated marginal means with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Mixed-models analysis was chosen to increase statistical power, due to large variability within the groups. Linear correlation analysis was used to explore possible associations between ex vivo MSC parameters with μCT-measured fracture healing parameters and serum markers. For correlation analysis, all data were checked for outliers. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.

Results

Both bolus and weekly ZA increased the bone mineral content and bone volume at the fracture site

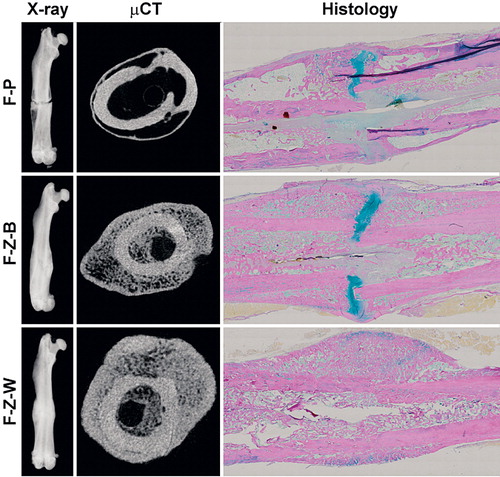

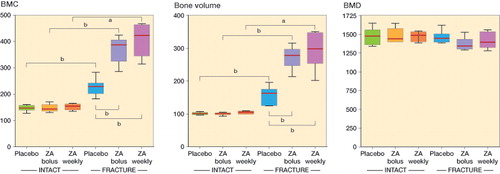

The health status of all animals was normal prior to fracture surgery and no adverse effects were observed during the follow-up. Radiography showed radiological union by 8 weeks regardless of treatment (). Callus formation appeared more extensive in ZA-treated rats, and μCT images and histological sections supported this finding. No apparent differences were detected between the bolus and weekly ZA treatment groups. As expected, μCT analysis showed statistically significantly greater BMC and BV in the callus areas of fractured femurs than in intact femurs, while the callus areas had similar BMD ( and ). In intact animals, no statistically significant differences were found between the placebo group, the weekly ZA treatment group, and the bolus ZA treatment group. When we compared ZA treatment and placebo treatment in animals with fracture, ZA treatment had the effect of increasing both femoral BMC and BV in callus areas. The weekly treatment group showed the highest average values of BMC and BV, but the difference was not statistically significant ().

Figure 1. Fracture healing. Representative images of fracture healing at 8-week endpoint presented as digital radiography (left panels), μCT section (center panels), and histological section (Weigert’s hematoxylin, Alcian blue, and van Gieson) (right panels) of rats treated with placebo (upper row), bolus ZA (middle row), and ZA on a weekly basis (bottom row).

Figure 2. μCT-based quantification of fracture callus and corresponding bone segment in intact animals. A and B. At the 8-week endpoint of the study, quantification of the apparent callus formation in the fracture animals confirmed statistically significantly increased bone mineral content (BMC) (panel A) and bone volume (BV) (panel B) compared to the corresponding intact groups (Mann-Whitney U-test). Both bolus ZA treatment and weekly ZA treatment resulted in significantly higher BMC and larger callus volume than in the placebo-treated fracture group (Mann-Whitney U-test). C. Neither ZA treatment nor fracture had any statistically significant effect on BMD (Student’s t-test). Data are median, with box plot whiskers showing range (min to max). a p < 0.05, b p < 0.01.

Weekly ZA treatment in vivo stimulated the ex vivo proliferation of MSCs isolated from intact animals, while ZA had no effect on osteoblastic differentiation

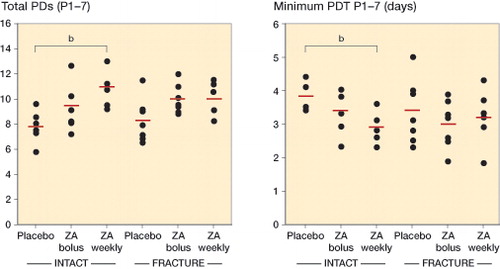

Similar numbers of BM cells were obtained from the different treatment groups (Figure 4, see Supplementary data), showing that the protocol was reproducible and that the baseline cell isolates were comparable. Detailed analysis revealed increased proliferation of MSCs from ZA-treated animals, especially in the intact group treated with ZA on a weekly basis, where the total number of PDs reached during 7 passages was higher (p = 0.007) and the average population doubling time (PDT) was shorter (p = 0.009). A similar trend was seen in animals with fracture (). The trend was similar for the maximum number of PDs reached during a single passage (P1–7), both in intact animals and in animals with fracture (Figure 4, see Supplementary data).

Figure 3. Proliferative capacity of rat MSCs. The long-term proliferative capacity was assessed as the total cumulative number of population doublings (total PDs) reached throughout passage 7 (P1–7) (panel A), while the proliferation rate was assessed as days per PD, and presented as minimum PD time in days recorded at a single passage (P1–7) (panel B). In the intact groups, MSCs from the animals treated with ZA on a weekly basis had a higher long-term proliferative capacity (p = 0.007) (A), and higher proliferation rate (p = 0.009) (B) compared to the corresponding placebo groups. All pairwise comparisons performed with Student’s t-test. Point graphs with mean value indication, b p < 0.01

MSCs from all groups were successfully induced into osteoblasts (Figure 5, see Supplementary data) but no statistically significant differences between the bolus or weekly ZA-treatment group and the placebo group were observed, either in intact animals or in animals with fracture (Figure 6, see Supplementary data). Interestingly, however, bolus ZA treatment resulted in the highest ALP activity and ALP-stained area, while weekly ZA treatment always gave the lowest levels, possibly indicating that bolus ZA treatment stimulated the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs—and/or that weekly ZA treatment suppressed it. We therefore compared each parameter further in the bolus ZA and weekly ZA groups, and found that bolus treatment did indeed result in higher ALP activities than weekly treatment, both in intact animals (p = 0.04) and in animals with fracture (p = 0.02). The inter-individual variation was remarkably high in ALP- and von Kossa-stained areas (Figure 6, see Supplementary data), thus diminishing the statistical power of analysis for these parameters.

ZA had no effect on serum bone markers at the 8-week endpoint, but animals with fracture had higher serum PINP levels

At the endpoint of the study (8 weeks), there were no detectable effects of ZA treatment on the levels of PINP and CTX markers. The results were the same whether analyses were performed on the separate treatment groups or whether the data from ZA-treated animals were pooled and compared against data from all placebo animals (data not shown). This justified the pooling of treatment groups for statistical analysis of the fracture effect. When all the animals with fracture were pooled as 1 group and all the intact animals were pooled as 1 group, there were no significant differences in CTX levels between the animals with fracture (30 (SD 13) ng/mL) and intact animals (30 (SD 10) ng/mL), while serum PINP levels were higher in animals with fracture than in intact animals (7.7 (SD 2.2) ng/mL vs. 6.6 (SD 1.3) ng/mL; p = 0.05).

Ex vivo osteoblastic differentiation of MSCs correlated with in vivo serum bone markers

There were correlations between serum PINP levels on the one hand and both cellular ALP activity (R = 0.44; p = 0.007) and ALP-stained areas (R = 0.32; p = 0.06) on the other, after 2 weeks of osteoblastic differentiation culturing. In line with this finding, an inverse correlation was observed between CTX and ALP (R = −0.33; p = 0.05). However, no associations were found between in vitro mineralization (von Kossa-stained area) and serum bone markers.

Discussion

This is the first study on the effects of in vivo-administered ZA and fracture on ex vivo properties of MSCs. MSCs isolated from bone marrow of ZA-treated rats were found to have increased proliferative capacity, but no substantial effects on osteoblastic differentiation were observed.

Interestingly, pro-proliferative effects of in vivo treatment with ZA on a weekly basis were detected several weeks after harvest, indicating that there might be something intrinsically different in those MSCs that have been in contact with ZA in vivo. One explanation would be that these MSCs show an increased stimulatory response in vitro, since MSCs from an osteogenically suboptimal in vivo environment are known to show increased responsiveness when transferred to more optimal in vitro conditions (Zhou et al. Citation2010).

Previous in vitro studies have found both stimulatory and inhibitory effects of BPs on osteoblastic cells. The contradictory results appear to depend on the source of cells and the type and concentration of bisphosphonate (Bellido and Plotkin Citation2011, Maruotti et al. 2012). BPs have been reported to increase bone tissue maturity (Gourion-Arsiquaud et al. Citation2010) and wall thickness in vivo, which reflects focally elevated osteoblast numbers or activity (Balena et al. Citation1993, Storm et al. Citation1993, Boyce et al. Citation1995). Interestingly, humans treated for 3 years with ZA showed an increased mineral apposition rate consistent with an increase in osteoblast activity (Recker et al. Citation2008), while others did not show such effects with other BPs (Chavassieux et al. Citation1997, Bravenboer et al. Citation1999). Our results indicate that in vivo ZA administration could be linked to stimulated MSC proliferation rather than increased osteogenesis, especially with weekly doses.

The degree of fracture healing at the 8-week endpoint is in line with the results of McDonald et al. (Citation2008), who clearly demonstrated that ZA treatment did not delay endochondral fracture repair but affected the callus remodeling, as well as giving increased callus strength compared to the placebo group. Weekly ZA dosing was associated with further increases in callus BMC and BV at 6, 12, and 26 weeks and delayed remodeling compared to single ZA dosing. Our results agree with these findings, even though we could only show a trend of increased callus BMC and BV in weekly dosing compared to single ZA dosing. There was a lower (but statistically insignificant difference in) BMD in the bolus ZA group with fracture than in the placebo group with fracture (p = 0.058). This was probably a reflection of the large fracture callus in the ZA bolus group—as indicated by the increased bone volume and subsequently increased total BMC—but consisting of immature bone tissue with a lower degree of mineralization per square cm.

Due to practical limitations, the present study was performed as 4 separate sub-series. Importantly, however, animals from each experimental group were randomly included in each series to strengthen the validity of the analysis. Conversely, the variation between individual animals and between different sub-series was a major limitation, making statistical analysis challenging and attenuating the statistical power. However, we chose to culture cells from each animal separately instead of pooling cells from different animals. This approach is especially relevant when one is aiming to apply data from a preclinical animal model to the clinical setting, since it mimics the true individual variation. This approach also enabled analysis of correlation between bone turnover in vivo and MSC differentiation capacity ex vivo.

To investigate bone turnover more mechanistically, we also evaluated the biochemical markers PINP and CTX in relation to fracture and/or ZA treatment. PINP levels at 8 weeks were higher in animals with fracture than in intact animals, indicating an active bone remodeling phase of fracture repair. However, no differences were observed in CTX levels. Surprisingly, ZA treatment had no effect on serum bone markers, although reduced marker levels were expected due to suppressed bone remodeling (Szulc Citation2012). Interestingly, we nevertheless observed that there was a positive correlation between PINP and the in vitro osteoblastic differentiation capacity of MSCs, while a negative correlation was observed with CTX, suggesting that in vitro investigation of the osteogenic capacity of BM cells can reflect the in vivo situation at the time of harvest.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the pro-proliferative effects of weekly ZA treatment in vivo can still be observed in isolated cells ex vivo several weeks after administration of the drug. However, the final conclusion as to whether this (a) is a direct effect of ZA on MSCs, (b) is an indirect effect mediated through ZA affecting other cells in the BM, or (c) reflects a compensatory response of MSCs upon “release” from BP-induced suppression of bone turnover, remains open. Although it is difficult to estimate how well our results can be translated into possible effects of ZA on BM cells in patients, our study strongly supports future research focusing on effects of BPs on osteoblast lineage cells to gain a better understanding of the mechanisms.

Supplementary data

Figures 4–6 are available on the Acta Orthopaedica website, www.actaorthop.org, identification number 9890.

Research design: TJH, JJA, and VVV. Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: TJH, JJA, HJH, and VVV. Drafting of the manuscript: TJH. Critical revision of the manuscript: TJH, JJA, and VVV. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This study was supported by the Turku University Foundation and the Finnish Cultural Foundation. We thank Miso Immonen, Liudmila Shumskaya, and Niko Moritz for technical assistance.

9890.pdf

Download PDF (1.2 MB)- Alm J J, Heino T J, Hentunen T A, Väänänen H K, Aro H T. Transient 100 nM dexamethasone treatment reduces inter- and intraindividual variations in osteoblastic differentiation of bone-marrow derived human mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Engineering Part C 2012; 18: 658–66.

- Balena R, Toolan B C, Shea M, Markatos A, Myers E R, Lee S C, Opas E E, Seedor J G, Klein H, Frankenfield D. The effects of 2-year treatment with the aminobisphosphonate alendronate on bone metabolism, bone histomorphometry, and bone strength in ovariectomized nonhuman primates. J Clin Invest 1993; 92: 2577–86.

- Bellido T, Plotkin L I. Novel actions of bisphosphonates in bone: preservation of osteoblast and osteocyte viability. Bone 2011; 49: 50–5.

- Bonnarens F, Einhorn T A. Production of a standard closed fracture in laboratory animal bone. J Orthop Res 1984; 2: 97–101.

- Boyce R W, Paddock C L, Gleason J R, Sletsema W K, Eriksen E F. The effects of risedronate on canine cancellous bone remodeling: three-dimensional kinetic reconstruction of the remodeling site. J Bone Miner Res 1995; 10: 211–21.

- Bravenboer N, Papapoulos SE, Holzmann P, Hamdy N A, Netelenbos J C, Lips P. Bone histomorphometric evaluation of pamidronate treatment in clinically manifest osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 1999; 9: 489–93.

- Chavassieux P M, Arlot M E, Reda C, Wei L, Yates A J, Meunier P J. Histomorphometric assessment of the long-term effects of alendronate on bone quality and remodeling in patients with osteoporosis. J Clin Invest 1997; 100: 1475–80.

- Fleisch H. Development of bisphosphonates. Breast Cancer Res 2000; 4: 30–4.

- Fromigué O, Body J J. Bisphosphonates influence the proliferation and the maturation of normal human osteoblasts. J Endocrinol Invest 2002; 25: 539–46.

- Giuliani N, Pedrazzoni M, Negri G, Passeri G, Impicciatore M, Girasole G. Bisphosphonates stimulate formation of osteoblast precursors and mineralized nodules in murine and human bone marrow cultures in vitro and promote early osteoblastogenesis in young and aged mice in vivo. Bone 1998; 22: 455–61.

- Gourion-Arsiquaud S, Allen M R, Burr D B, Vashishth D, Tang S Y, Boskey A L. Bisphosphonate treatment modifies canine bone mineral and matrix properties and their heterogeneity. Bone 2010; 46: 666–72.

- Heino T J, Hentunen T A, Väänänen H K. Conditioned medium from osteocytes stimulates the proliferation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and their differentiation into osteoblasts. Exp Cell Res 2004; 294: 458–68.

- Hiltunen A, Vuorio E, Aro H T. A standardized experimental fracture in the mouse tibia. J Orthop Res 1993; 11: 305–12.

- Im G I, Qureshi S A, Kenney J, Rubash H E, Shanbhag A S. Osteoblast proliferation and maturation by bisphosphonates. Biomaterials 2004; 25: 4105–15.

- Li J, Mori S, Kaji Y, Mashiba T, Kawanishi J, Norimatsu H. Effect of bisphosphonate (incadronate) on fracture healing of long bones in rats. J Bone Miner Res 1999; 14: 969–79.

- Li J, Mori S, Kaji Y, Kawanishi J, Akiyama T, Norimatsu H. Concentration of bisphosphonate (incadronate) in callus area and its effects on fracture healing in rats. J Bone Miner Res 2000; 15: 2042–51.

- Maruotti N, Corrado A, Neve A, Cantatore F P. Bisphosphonates: effects on osteoblast. Eur J Clin Pharmacol; 68: 1013–8.

- McDonald M M, Dulai S, Godfrey C, Amanat N, Sztynda T, Little D G. Bolus or weekly zoledronic acid administration does not delay endochondral fracture repair but weekly dosing enhances delays in hard callus remodeling. Bone 2008; 43: 653–62.

- Pan B, To L B, Farrugia A N, Findlay D M, Green J, Gronthos S, Evdokiou A, Lynch K, Atkins GJ, Zannettino A C. The nitrogen-containing bisphosphonate, zoledronic acid, increases mineralisation of human bone-derived cells in vitro. Bone 2004; 34: 112–23.

- Recker R R, Delmas P D, Halse J, Reid I R, Boonen S, Garcia-Hernandez P A, Supronik J, Lewiecki E M, Ochoa L, Miller P, Hu H, Mesenbrink P, Hartl F, Gasser J, Eriksen E F. Effects of intravenous zoledronic acid once yearly on bone remodeling and bone structure. J Bone Miner Res 2008; 23: 6–16.

- Reinholz G G, Getz B, Pederson L, Sanders E S, Subramaniam M, Ingle J N, Spelsberg T C. Bisphosphonates directly regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, and gene expression in human osteoblasts. Cancer Res 2000; 60: 6001–7.

- Rogers M J. New insights into the molecular mechanisms of action of bisphosphonates. Curr Pharm Des 2003; 9: 2643–58.

- Salmon P L. Bone micro-CT analysis. A short guide to analysis of bone by micro-CT. SkyScan, Kontich, Belgium 2005.

- Storm T, Steiniche T, Thamsborg G, Melsen F. Changes in bone histomorphometry after long-term treatment with intermittent, cyclic etidronate for postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 1993; 8: 199–208.

- Szulc P. The role of bone turnover markers in monitoring treatment in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Clin Biochem 2012; 45: 907–19.

- Välimäki V V, Moritz N, Yrjans J J, Vuorio E, Aro H T. Effect of zoledronic acid on incorporation of a bioceramic bone graft substitute. Bone 2006; 38: 432–43.

- Zhou S, LeBoff M S, Glowacki J. Vitamin D metabolism and action in human bone marrow stromal cells. Endocrinology 2010; 151: 14–22.