Abstract

Background and purpose — Soft-tissue sarcoma (STS) is rare, with challenging individualized treatment, so diagnostics and treatment should be centralized. Historical controls are sometimes used for investigation of whether new diagnostic or therapeutic tools affect patient outcome. However, as yet unknown factors may affect the outcome. We investigated prognostic factors and prognosis in 2 nationwide cohorts of patients diagnosed with a local STS during the periods 1998–2001 and 2005–2010, with special interest in finding factors lying behind possible improvement of prognosis.

Patients and methods — 2 cohorts of patients with STS of the extremities or trunk diagnosed during the periods 1998–2001 and 2005–2010 were retrieved from the nationwide Finnish Cancer Registry. Detailed information was gathered from patient files.

Results — Compared to first cohort, a larger proportion of patients with inadequate surgery in the second cohort received radiation therapy, and both the local control rate and the sarcoma-specific survival rate improved in the second cohort. For sarcoma-specific survival, cohort (HR =0.6, 95% CI: 0.5–0.9), age, depth, grade, and margin were significant factors in multivariate analysis. For local control, cohort (HR =0.6, 95% CI: 0.5–0.9), age, and margin were significant in multivariate analysis.

Interpretation — Known prognostic factors including type of treatment did not entirely explain the secular trend of continuous improvement in prognosis in STS. This illustrates the danger of using historical controls for investigation of whether new diagnostic or therapeutic tools have an effect on patient outcome.

Treatment of soft-tissue sarcoma (STS) is highly demanding and it should—by consensus—be centralized in large centers with adequate experience. Primary treatment of localized STS has for a long time been surgery with clear margins, and this has been increasingly combined with (neo-) adjuvant radiation therapy. The role of adjuvant chemotherapy remains unclear, and the estimated benefit, if any, remains small (Pervaiz et al. Citation2008). The main treatment principles have remained the same for several decades (Leyvraz et al. Citation2005, ESMO Citation2014).

The prognosis of STS has gradually improved during the last decades despite the fact that there has been no major breakthrough in the principles of treatment of the disease. In Finland, the 5-year survival has stayed the same (67–66%) in men but it increased in women from 58% in 1999–2003 to 68% in 2009–2013, and the trend has been similar in other Nordic contries (Bray et al. Citation2010, Engholm et al. Citation2016). The Scandinavian Sarcoma Group (SSG) introduced a treatment program for soft-tissue sarcoma (SSG V) in 1986, and the protocol was widely adopted in Finland. We have reported the benefit of firm adherence to treatment protocol at the largest tertiary sarcoma referral center in Finland—Helsinki University Hospital (Wiklund et al. Citation1996, Sampo et al. Citation2008). In a Swedish SSG study, metastasis-free survival improved between 2 cohorts at Karolinska Hospital from 57% (in patients treated 1986–1989) to 75% (in patients treated 1997–2002). Better referral policy for smaller lesions at least partly explained the improvement, but a question was raised as to whether other underlying reasons might also have been responsible for the better outcome (Bauer et al. Citation2004).

The main aim of the present study was to investigate prognostic factors and prognosis in 2 nationwide patient cohorts diagnosed with a local STS during the periods 1998–2001 and 2005–2010. We were especially interested in finding factors responsible for possibly improved prognosis.

Material and methods

Data for patients diagnosed with a local STS of the extremity or trunk wall in Finland during 1998–2001 and 2005–2010 were retrieved from the nationwide population-based Finnish Cancer Registry. The Finnish Cancer Registry covers more than 99% of the solid tumors diagnosed in Finland (Teppo et al. Citation1994, Forman et al. Citation2014).

Detailed clinical data were collected from the patient files. Patients with dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, grade-I liposarcoma/atypical lipoma, and cutaneous leiomyosarcoma were excluded from the analysis. 2 patients were excluded because of missing files. We also excluded patients who received treatment with palliative intention, leaving 215 patients during the period 1998–2001 and 359 patients during 2005–2010 for analysis, all of whom had primary local STS of the extremities or trunk.

Helsinki University Hospital (HUH) has weekly multimodality STS meetings and has long been the main center for STS treatment. Consultations from other university hospitals (Tampere, Turku, Oulu, Kuopio) are also referred to Helsinki. HUH treated 177 (105) patients and the other 4 university hospitals treated 28–69 (8-28) patients each. (The numbers in parentheses refer to patients who were treated during the period 1998–2001). Only 1–3 patients were treated at each of 14 (17) other institutions (district hospitals and primary healthcare units). Altogether, definite surgeries were performed at 19 institutions during 2005–2010 and at 23 institutions during 1998–2001.

Definitions of surgical margins were adapted from the Enneking classification (Enneking et al. Citation1981). In Helsinki, the surgical margin was defined as wide if the smallest microscopic margin in the fixed specimen measured at least 2.5 cm. In some university hospitals in Finland, the cutoff point is 1 cm and the margin was defined accordingly. A smaller margin was accepted as being wide, however, if it consisted of an anatomical barrier with no involvement (such as fascia). If the requirements for a wide margin were not fulfilled, the margin was classified as marginal (margins negative but less than 2.5 cm (1 cm) wide) or as intralesional (microscopic or macroscopic tumor left). The mean length of follow-up of the survivors was 5.2 (2.2–9.4) years for the 2005–2010 cohort and 7.0 (0.6–12) years for the 1998–2001 cohort.

Statistics

Possible differences in tumor, patient, and treatment characteristics in the 2 cohorts were assessed with the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test. Local recurrence-free rates, metastasis-free rates, and sarcoma-specific survival rates were calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method. If the univariate test showed a significant association (p ≤ 0.05) between a descriptive variable and the survival rate, this variable was included in a Cox proportional hazards model for multivariate analysis. IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 was used for all analyses.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Joint Ethics Committee of Helsinki University Hospital (270/13/03/00/2001, 5.8.2014) and by the National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL/919/5.05.00/2014, 29.12.2014).

Results

The only statistically significant difference between the 2 cohorts was a shift in histological diagnosis (). Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma was the commonest subtype in both cohorts. More patients had preoperative histology needle biopsy in the second cohort, although as many as one quarter of patients in the second cohort were operated without any previous biopsy (). Of the patients referred to STS centers in the 5 university hospitals for treatment of primary tumors, the percentage of untouched tumors increased from 45% to 54%.

Table 1. Patient and tumor characteristics in patients of the 2 cohorts

Table 2. Characteristics of diagnostics and treatment in the 2 cohorts

Compared to the first cohort, more patients in the 2005–2010 cohort had only 1 definite operation, more patients had a wide definite margin, more patients with an inadequate margin received radiation therapy, and more patients received chemotherapy ().

Surgery and complications

Of the 359 patients, 251 (70%) did not require any reconstruction after resection of the tumor (skin transplants excluded). 54 patients (15%) required pedicled flap reconstruction, 38 (11%) required microvascular flap reconstruction, 6 patients required vascular reconstruction, and 10 patients required reconstruction with surgical mesh. The complication rate was not associated with the number of primary surgeries. The 30-day complication rate after definite surgery was 26%. When only major complications were considered (treatment-related death, hematoma evacuation/infection requiring further surgery, infection requiring intravenous antibiotics, re-anastomosis, revision requiring pedicled or microvascular flap), the rate was 17%. 2 treatment-related deaths were recorded: 1 patient developed a major stroke after surgery and 1 patient developed systemic infection and empyema after reconstruction with pedicled latissimus dorsi flap and surgical mesh.

Radiation therapy

Of the patients with an inadequate definite margin (intralesional or marginal), 78% in the second cohort received adjuvant radiation therapy as compared to 66% in the first cohort.

Survival

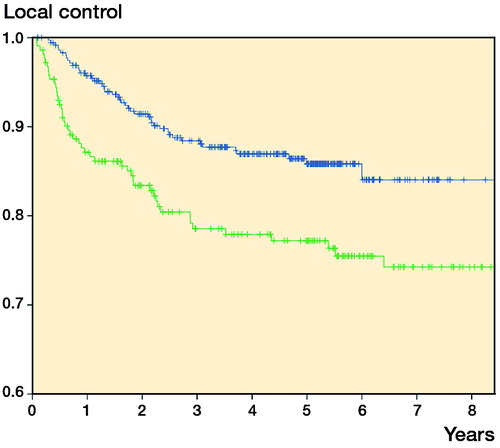

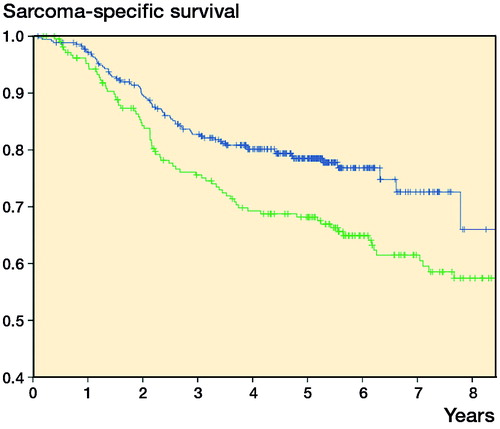

Both local recurrence-free survival (5-year LRFS; 86% vs. 77%) and sarcoma-specific survival (5-year survival; 79% vs. 68%) improved in the second cohort ( and ). Metastasis-free survival also improved (5-year MFS; 73% vs. 67%; p = 0.05).

Factors affecting local control and sarcoma-specific survival

In univariate analysis, second vs. first cohort (HR =0.6, 95% CI: 0.4–0.8), younger age, and wider margin gave better local control. In multivariate analysis, these factors all remained statistically significant ().

Table 3. Uni- and multivariate analyses on prognostic factors for local recurrence

For metastases-free survival, depth, grade, margin, sex, size, and radiation therapy were of prognostic value in univariate analysis. Second vs. first cohort (HR =0.7, 95% CI: 0.5–1.0) and age were of borderline significance. Grade, margin, size, and sex were statistically significant in multivariate analysis ().

Table 4. Uni- and multivariate analyses on prognostic factors for metastases

For sarcoma-specific survival, second vs. first cohort (HR =0.6, 95% CI: 0.4–0.8), age, depth, grade, and margin were of prognostic value in univariate analysis. They all remained statistically significant in multivariate analysis ().

Table 5. Uni- and multivariate analyses on prognostic factors for sarcoma-related death

Discussion

5-year local recurrence-free survival improved by 9% and sarcoma-specific survival by 11% between the 2 cohorts (1998–2001 and 2005–2010). Finnish Cancer Registry data showed an 8% improvement in overall survival during the corresponding decade (1999–2003 to 2009–2013) (Engholm et al. Citation2016). The somewhat larger improvement in our study may be explained by different endpoint (cancer-specific as opposed to age-adjusted overall survival) and the fact that only patients treated with curative intent were included in our analysis. In a SEER study from the USA, the improvement was even more impressive; 5-year overall survival improved by 32% over 13 years from 1991–1996 to 2004–2010 (Jacobs et al. Citation2015). During this period, the treatment modalities have been practically the same.

In the present study, the cohorts (1998–2001 vs. 2005–2010) showed independent prognostic value for local control and sarcoma-specific survival in both univariate and multivariate analysis. Part of the improvement in outcome might probably be explained by improved diagnostics and better adherence to treatment recommendations, because patients had fewer operations for the primary tumor, had better surgical margins, and had more use of radiation therapy and chemotherapy in the second cohort. Multivariate analyses, where these factors were adjusted for, still showed a statistically significant effect of the cohort on local control and disease-specific survival, indicating that these factors did not completely capture all the factors responsible for the improvement in outcome. In an SSG registry material from Karolinska Hospital, not only local control but also metastasis-free survival improved (57% vs. 75%) in soft-tissue sarcoma patients (treated in the period 1986–1989 or in the period 1997–2002, respectively) (Bauer et al. Citation2004). Some of the improvement was due to improved referral policy including more patients with small and superficial tumors, but the authors speculated that this alone might not explain the dramatic survival benefit. Unfortunately, sarcoma-specific survival was not reported.

The retrospective setting of our study can be seen as a weakness, with data gathered primarily for reasons other than research purposes. Patients with poor physical performance status or substantial comorbidities, with only palliative treatment, were excluded. Because there were few histotype changes at histological review in our previous study due to centralized pathology diagnostics (Sampo et al. Citation2012), no histological review was performed in the present study. Heterogenous definitions of wide surgical margins and different selection criteria for patients receiving radiation therapy may cause inaccuracy in the local control analysis. The strength of the study was the truly nationwide cohort based on the reliable Finnish Cancer Registry, with almost 100% completeness regarding solid tumors (Teppo et al. Citation1994, 2014).

Awareness of sarcoma treatment guidelines among physicians who see patients presenting with soft-tissue masses remains unsatisfactory in Finland, as only 55% of patients were referred to an STS center untouched during the period 2005–2010. The proportion is higher than during 1998–2001 (41%), but it leaves room for improvement.

In summary, both local control rate and sarcoma-specific survival improved over time. Known prognostic factors or type of treatment did not entirely explain this improvement, suggesting the presence of other as yet unknown factors. Our findings make the use of historical controls for evaluation of new treatment forms questionable.

MMS, KK, EJT, TOB, and CPB designed the study. MMS and KK collected the data, MMS and CPB analyzed it, and MMS wrote the first draft of the manuscript and took care of its revisions. All the authors contributed to interpretation of the results and preparation of the manuscript.

We are grateful for financial support from the Competitive Research Funding of Helsinki University Hospital and the Finnish Cancer Society.

No competing interests declared.

- Bauer H C, Alvegard T A, Berlin O, Erlanson M, Kalen A, Lindholm P, Gustafson P, Smeland S, Trovik C S. The Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Register 1986-2001. Acta Orthop Scand 2004; 75 (Suppl 311): 8–10.

- Bray F, Engholm G, Hakulinen T, Gislum M, Tryggvadottir L, Storm H H, Klint A. Trends in survival of patients diagnosed with cancers of the brain and nervous system, thyroid, eye, bone, and soft tissues in the Nordic countries 1964-2003 followed up until the end of 2006. Acta Oncol 2010; 49(5): 673–693.

- Engholm G F J, Christensen N, Kejs AMT, Johannesen TB, Khan S, Leinonen M, Milter MC, Ólafsdóttir E, Petersen T, Stenz F, Storm HH. NORDCAN: Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Prevalence and Survival in the Nordic Countries.Version 7.2 (22.4.2016). Association of the Nordic Cancer Registries. Danish Cancer Society. Available from http://www.ancr.nu, accessed on 22.4.2016.

- Enneking W F, Spanier S S, Malawer M M. The effect of the Anatomic setting on the results of surgical procedures for soft parts sarcoma of the thigh. Cancer 1981; 47(5): 1005–1022.

- ESMO. Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2014; 25Suppl3(1569-8041 (Electronic)): iii102–112.

- Forman D, Bray F, Brewster D H, Gombe Mbalawa C, Kohler B, Piñeros M, SteliarovaFoucher E, Swaminathan R, Ferlay J. editors, (2014). Cancer incidence in five continents, Vol. X. (electronic version). Lyon. IARC Scientific Publication. Available from http://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/epi/sp164/, accessed 22.4.2016.

- Jacobs A J, Michels R, Stein J, Levin A S. Improvement in overall survival from extremity soft tissue sarcoma over twenty years. Sarcoma 2015; 2015(279601).

- Leyvraz S, Jelic S, Force E G T. ESMO Minimum Clinical Recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of soft tissue sarcomas. Ann Oncol 2005; 16Suppl1(i69-70).

- Pervaiz N, Colterjohn N, Farrokhyar F, Tozer R, Figueredo A, Ghert M. A systematic meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of adjuvant chemotherapy for localized resectable soft-tissue sarcoma. Cancer 2008; 113(3): 573–581.

- Sampo M, Tarkkanen M, Huuhtanen R, Tukiainen E, Bohling T, Blomqvist C. Impact of the smallest surgical margin on local control in soft tissue sarcoma. Br J Surg 2008; 95(2): 237–243.

- Sampo M M, Ronty M, Tarkkanen M, Tukiainen E J, Bohling T O, Blomqvist C P. Soft tissue sarcoma - a population-based, nationwide study with special emphasis on local control. Acta Oncol 2012; 51(6): 706–712.

- Teppo L, Pukkala E, Lehtonen M. Data quality and quality control of a population-based cancer registry. Experience in Finland. Acta Oncol 1994; 33(4): 365–369.

- Wiklund T, Huuhtanen R, Blomqvist C, Tukiainen E, Virolainen M, Virkkunen P, Asko-Seljavaara S, Bjorkenheim J M, Elomaa I. The importance of a multidisciplinary group in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas. Eur J Cancer 1996; 32A(2): 269–273.