Abstract

Background and purpose — Stability and survival of cemented total hip prostheses is dependent on a multitude of factors, including the type of cement that is used. Bone cements vary in viscosity, from low to medium and high. There have been few clinical RSA studies comparing the performance of low- and high-viscosity bone cements. We compared the migration behavior of the Stanmore hip stem cemented using novel low-viscosity Palamed bone cement with that of the same stem cemented with conventional high-viscosity Palacos bone cement.

Patients and methods — We performed a randomized controlled study involving 39 patients (40 hips) undergoing primary total hip replacement for primary or secondary osteoarthritis. 22 patients (22 hips) were randomized to Palacos and 17 patients (18 hips) were randomized to Palamed. Migration was determined by RSA.

Results — None of these 40 hips had been revised at the 10-year follow-up mark. To our knowledge, the patients who died before they reached the 10-year endpoint still had the implant in situ. No statistically significant or clinically significant differences were found between the 2 groups for mean translations, rotations, and maximum total-point motion (MTPM).

Interpretation — We found similar migration of the Stanmore stem in the high-viscosity Palacos cement group and the low-viscosity Palamed cement group. We therefore expect that the risk of aseptic loosening with the new Palamed cement would be comparable to that with the conventional Palacos cement. The choice of which type of bone cement to use is therefore up to the surgeon’s preference.

Aseptic loosening of cemented hip prostheses, the main indication for revision surgery, accounts for approximately 60% of cases (Garellick et al. Citation2012, (LROI) Citation2013, van Steenbergen et al. Citation2015). Currently, mostly high- and medium-viscosity bone cements are used in THR. Low-viscosity cements were introduced about 2 decades ago. The theoretical advantages of low-viscosity cements are easier handling during cementation due to reduced “stickiness” and longer “workable time” during implantation. Furthermore, it is claimed that low-viscosity cement provides improved penetration of cement into the trabecular bone and a lower curing temperature, which presumably leads to less trabecular bone necrosis. However, there has been a lack of clinical trials to investigate whether these presumed advantages are actually experienced in practice (Hallan et al. Citation2006).

Migration of orthopedic implants can be assessed with sub-millimeter accuracy using radiostereometric analysis (RSA) (Selvik Citation1989, Malchau et al. Citation1995, Kaptein et al. Citation2007). Early (2-year) migration has been shown to be associated with late (10-year) prosthetic failure caused by aseptic loosening. Early migration can therefore be used as a predictor of this specific mode of failure at long-term follow-up, and it should thus be part of a phased introduction of new implants or new bone cements (Karrholm et al. Citation1994, Ryd et al. Citation1995, Karrholm et al. Citation1997).

We compared low-viscosity Palamed bone cement with high-viscosity Palacos bone cement, which can be considered the “gold standard” of high-viscosity bone cements due to its widespread use and good clinical performance (Havelin et al. Citation1995, Espehaug et al. Citation2002, Hallan et al. Citation2006). We used a collared Stanmore stem, which is a composite-beam (shape closed) stem that has shown excellent results and long-term survival when fixed with high-viscosity cement (Alsema et al. Citation1994, Emery et al. Citation1997, Gerritsma-Bleeker et al. Citation2000).

The main aim of this randomized controlled study was to compare the migration behavior of the Stanmore hip stem cemented with novel low-viscosity Palamed and the same stem cemented with conventional high-viscosity Palacos bone cement. A secondary aim was to compare the clinical outcome of both groups.

Patients and methods

A consecutive series of 40 cemented hip stems was included between October 2001 and April 2004 in our department. The department’s policy on THR is as follows. If patients are older than 65 years, they undergo cemented arthroplasty, and if they are younger, they undergo cementless arthroplasty. The implant used in all patients was the standard (i.e. slightly curved) Stanmore hip stem, which consists of a collared femoral cobalt-chromium-molybdenum (Co-Cr-Mo) stem with a modular head (28 mm in diameter). In all patients, this stem was paired with an ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWP) cup (Biomet, Warsaw, IN).

Patients were considered eligible for participation if they underwent THR for primary or secondary osteoarthritis of the hip. Patients were excluded if they were unable or unwilling to sign the informed consent document, or if the indication for surgery was revision of a previously failed hip replacement.

Patients were randomized for the type of cement by drawing closed envelopes assigning them to a specific group. The randomization process, whereby the surgeons were blinded, was performed by the data manager of the department and the type of cement to be used was passed on to the operating team within 24 h before surgery. Both the patients and the observers were blinded regarding the type of bone cement used during surgery.

Both cement types were provided in the form of 2 pre-measured sterilized components (i.e. a powder and a liquid) that formed radiopaque bone cement after mixing. Both types of bone cement were mixed using the same kind of vacuum-mixing system at room temperature. After reaming of the femur, the femoral canal was cleaned using a pulse-lavage system and a Biosem resorbable cement-stop was introduced. After retrograde pressurization of the cement, the stem was introduced and excess cement was removed.

All prostheses were implanted using the direct lateral approach (Hardinge Citation1982). For RSA measurements, 3–8 tantalum markers (1 mm in diameter) were inserted into the greater and lesser trochanter region during surgery. The patients were kept from weight bearing until the first RSA radiograph was taken (on the first or second postoperative day) and they were then allowed full weight bearing. All patients were treated with coumarins until 6 weeks after surgery, to prevent venous thrombosis.

The patients were evaluated preoperatively and postoperatively at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year—and annually thereafter. At each evaluation, the Harris hip score was obtained and an RSA radiograph was taken. Conventional anteroposterior pelvic and lateral radiographs were acquired at 6 weeks, 2 years, 5 years, and 10 years postoperatively and on indication (e.g. in case of pain or suspected failure). The femoral and acetabular components were considered a radiographic failure when there were cement cracks, when there was complete progressive radiolucency of 2 mm or more, or when there was fracture of the stem (Gruen et al. Citation1979, Johnston et al. Citation1990).

RSA radiographs were obtained using a uniplanar setup with the patient in supine position and the calibration cage under the examination table. In 2002, the calibration cage was changed from “large reference box Leiden” to “Carbon box Leiden”. In 2004, the conventional radiography system was replaced with a digital radiography system (PACS). Both changes had no effect on the accuracy of the RSA measurements; this was previously determined in another RSA study that ran simultaneously with the present study and used the same setup (Nieuwenhuijse et al. Citation2012).

Using the bone markers placed in the femur around the implant as fixed reference and plotting a virtual model of the stem (elementary geometric shapes (EGS) model) by marking the region of interest of the tip, cone of the stem, and the head separately, migration was analyzed (MB-RSA software version 4; RSAcore, LUMC, Leiden, the Netherlands) (Prins et al. Citation2008). The first RSA examination served as baseline reference for all further examinations, and all evaluations were related to the position of the prosthesis relative to the bone at that time. However, in 3 patients (4 hips, 1 Palacos and 3 Palamed) the postoperative images were not usable because of poor image quality. In these patients, the 6-week follow-up images were used as a reference.

Migration was measured as translations along and as rotations about the 3 orthogonal axes: transverse, longitudinal, and sagittal, and also as the length of a vector that combines the migration in all directions (i.e. maximum total-point motion, MTPM). According to the ISO standard 16087, the terms mediolateral, craniocaudal, and anteroposterior translation will be used for movement along the x-, y-, and z-axes, respectively. For rotations about these axes, the terms flexion-extension, endo-exo, and mediolateral rotation will be used (ISO/TC 150 committee (Implants for Surgery 2013).

On the 6-week postoperative standard anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the hip, the stem orientation (i.e. varus or valgus) and cement mantle thickness were measured. Minimal and maximal cement mantle thicknesses were measured in all 14 Gruen zones, and the quality of cement penetration was scored for the hip stem according to Barrack et al. (Citation1992).

Characteristics of the study population

39 consecutive patients with 40 primary cemented THRs were included. The indication for THR was primary osteoarthritis in 29 patients (30 hips) and secondary osteoarthritis in 10 patients (10 hips). 17 patients (18 hips) were assigned to the low-viscosity cement (Palamed) group and 22 patients (22 hips) were assigned to the high-viscosity cement (Palacos) group. Stem size 1 was used in 2 hips, stem size 2 in 16 hips, stem size 3 in 20 hips, and stem size 4 in 2 hips. The neck length of the prosthesis could be modulated by the surgeon between −6 and +12 mm; the −3 mm length was used in 3 hips, the standard size (+0 mm) was used in 14 hips, +3 mm in 14 hips, +6 mm in 6 hips, +9 mm in 2 hips, and +12 mm in 1 hip (). At 10-year follow-up, no THRs had been revised. 27 patients (28 hips) were lost to follow-up before they reached 10-year follow-up. 17 patients died, 7 patients moved to another region, and 3 patients did not want to participate any more for reasons unrelated to the study (i.e. dementia in 2 patients and cardiac failure in 1 patient). These patients were contacted by the investigator (JM) to check whether the implant was still in situ, or whether any problems possibly related to the THR had arisen in the meantime. Mean length of follow-up was 7 (1–10) years. Follow-up of at least 10 years was available for 12 patients (12 hips); the number of usable RSA examinations per group at the different follow-up intervals is depicted in Figure 1 (see Supplementary data).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics. Data are mean (SD) unless otherwise stated

The mean condition number (CN) and the mean rigid body error of the markers of the femur were in accordance with the RSA guidelines and ISO standard 16087 (Valstar et al. Citation2005, ISO/TC 150 Committee Citation2013) (). The precision of the RSA measurements was determined using 12 double examinations (i.e. involving 30% of the total study population) taken at 1-year follow-up (Ranstam et al. Citation2000). The precision (i.e. the upper 95% CI limit) of the RSA examinations was 0.04, 0.13, and 0.33 mm for translations and 0.67, 0.75, and 0.23 degrees for rotations on the transverse, longitudinal, and sagittal planes, respectively (). 6 RSA radiographs in 6 patients had to be excluded due to technical problems. In 4 patients (4 hips: 2 Palacos and 2 Palamed), only 2 bone markers could be matched consistently over time in the RSA images. In 3 other patients (3 hips: 2 Palacos and 1 Palamed), the condition number exceeded 120 because the markers were positioned almost collinearly (Ranstam et al. Citation2000). The translation data for these 7 hips could be used for analysis; rotations and MTPM measurements of these hip stems were excluded from analysis, however. 1 patient (1 hip) had a postoperative wound infection, which required surgical debridement in combination with the placement of gentamicine beads and antibiotics for 6 weeks. This treatment was successful and there was no need to revise the prosthesis. Up to the 10-year follow-up point, the implant remained in situ and the patient had few complaints about the affected hip. Even so, the RSA data obtained from this patient were excluded from final analysis because the bone markers themselves started to migrate after the surgical debridement, which resulted in a mean error (ME) of over 0.35 mm.

Table 2. RSA measurement values; mean (SD)

Table 3. Precision of RSA measurements (upper limits of 95% CI)

Mean stem orientation, minimum and maximum cement mantle thickness, and cement penetration were similar in the 2 groups (). The Harris hip score (HHS) in both groups increased postoperatively relative to preoperatively, and remained stable for the rest of the duration of follow-up. The preoperative scores and those at the different follow-up points were equally distributed between the 2 groups and did not show any statistically significant differences (Table 4, see Supplementary data).

Statistics

To account for the longitudinal nature of the data and repeated measurements in the same patient, migration was analyzed by using a linear mixed model with random intercepts and random slopes (Crowder and Hand Citation1990). Adjusted means with their corresponding 95% CI provided by the mixed model are given. Other outcomes of interest are reported as mean and standard deviation (SD). All available examinations that met the criteria described in ISO standard 16087 were included in the analysis, and the mean for every follow-up occasion represents the mean migration of all available prostheses (patients). Cement type, follow-up interval, operation indication/diagnosis, sex, and BMI were successive covariates in analysis of migration. HSS was compared between groups using ANOVA.

The p-values (provided by the test for fixed effects, for the covariates cement type and follow-up interval) defined whether the probability of finding a difference in mean migration between the 2 different cement types was significant over the total duration of follow-up. Any p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. SPSS software version 20.0 was used.

Ethics

Approval from the institutional medical ethics committee was obtained (ethical approval no. P00.166), and all the patients gave written informed consent.

Results

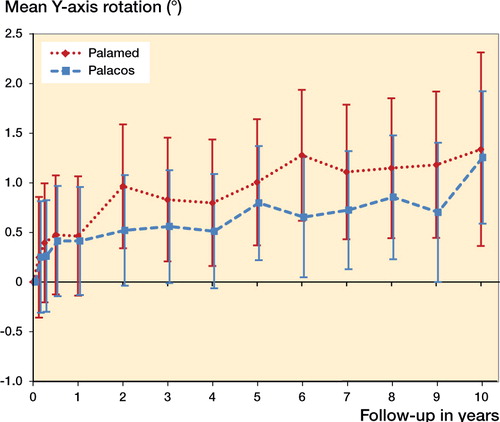

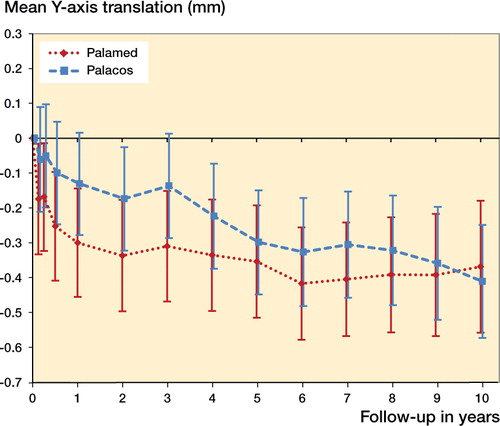

Translations, rotations, and MTPM of the stem were comparable in the Palacos group and the Palamed group at the 1-, 5-, and 10-year follow-up (). The mean MTPM over time was comparable in the 2 groups (Figure 2, see Supplementary data), as was the mean mediolateral translation (Tx) per group over time (Figure 3, see Supplementary data). In both cement groups, a small amount of caudal translation (i.e. subsidence) of the stem was measured (). About half of the total craniocaudal translation (Ty) occurred in the first 2 years after surgery. These values stabilized afterwards and were not statistically significantly different over the total duration of follow-up. There was no significant difference in anteroposterior translation (Tz) between groups. Both the Palacos group and the Palamed group showed a sub-millimeter mean posterior translation, which remained stable over time (Figure 5, see Supplementary data).

Figure 4. Mean craniocaudal (Ty) translation in mm per group with 95% CI of the estimated marginal means per follow-up interval.

Table 5. Mean migration in mm or degrees with lower and upper limits of 95% CI provided by the mixed model

Mean flexion-extension rotation (Rx) for the Palacos and Palamed groups was comparable over the different follow-up points (Figure 6, see Supplementary data). The mean rotation about the flexion-extension axis did not exceed 0.5°, which was below the upper limit of the 95% CI, indicating precision of RSA measurement in this study for rotations about that axis (). In both groups, the implant rotated internally and stabilized at about 1.0° of positive mean internal-external rotation (Ry) (). Both the Palacos group and the Palamed group showed a small amount of lateral rotation over time. The mean abduction-adduction rotation (Rz) remained stable and did not exceed −0.5° in either group (Figure 8, see Supplementary data).

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study is the first randomized controlled RSA trial to compare Palacos and Palamed bone cement in THR in which the medium- and long-term follow-up RSA results are also reported. Migration in the 2 cement groups was comparable at short-term (1-year), medium-term (5-year), and long-term (10-year) follow-up. The Palamed group did show a consistently higher mean subsidence (Ty) and also more internal rotation (Ry). However, these differences never reached statistically significant levels. Most migration occurred in the first 2 years postoperatively, after which a steady state was reached. The migrations observed were well within the limits predicting a good long-term performance of the THR (Karrholm et al. Citation1994, Kobayashi et al. Citation1997). Both cement types provided proper fixation of the implant for up to 10 years at least after surgery. This is consistent with other studies that have assessed the clinical results and the mechanical properties of Palacos and Palamed bone cement (Mjoberg et al. Citation1987, Espehaug et al. Citation2002, Kienapfel et al. Citation2004, Hallan et al. Citation2006, Gravius et al. Citation2007).

Compared to the randomized controlled RSA trial by Hallan et al. (Citation2006) with 2-year follow-up, which compared Palacos and Palamed bone cement in combination with the Charnley stem, the mean migration values in our study are slightly different. However, the 95% CIs of the mean values are comparable. The small difference in mean migration at 2-year follow-up between that study and our study might therefore very well be explained by the difference in stem design.

One weakness of the present study was the small number of patients that reached the 10-year follow-up endpoint. This can largely be explained by the high age at baseline of the patients included, which resulted in 17 deaths before the endpoint—all unrelated to the implant or operation. Furthermore, 10 patients were lost to follow-up because they moved to another region or because continuing participation was too demanding for the patient and caretakers. This resulted in a rapid decline in the number of patients after the 7-year interval. The data obtained from the 12 patients who did make it to the 10-year endpoint met the criteria and still provided enough material to perform the mixed model analysis for that interval, but with a larger estimated 95% CI of the mean. Due to the relatively short follow-up after the large decline in participants at 7 years, we must express caution regarding the lack of a statistically significant difference in loosening between the 2 groups, as there may have been type-II error.

Another weakness was that rotations and MTPM could not be calculated in 7 patients. This was due to collinearly of implanted markers or because only 2 markers could be consistently matched over time (resulting in a CN of >120). All translations measured provided valuable data, however, and were included in the final analysis. The distribution of these patients between the groups was also comparable (4 out of 20 in the Palacos group as compared to 3 out 18 in the Palamed group), and would therefore not cause any over- or underestimation of the migration in either group.

Even though Palamed was introduced to the market in 1998, we started a randomized controlled trial in 2001, 3 years later. It would have been preferable to study the migration behavior before market introduction, as proposed by Malchau (Citation1995). Fortunately, we found that Palamed provided fixation of the implant that was as good as that with the well-established Palacos bone cement.

In conclusion, we found no statistically significant differences in mean migration for any of the axes, in MTPM, or in clinical outcome between the groups after 10 years of follow-up. We therefore conclude that low-viscosity Palamed bone cement provides as good fixation of the femoral component in THR as high-viscosity Palacos bone cement. The choice of which bone cement to use should therefore rest on the preferences of the surgeon.

Supplementary data

Table 4 and Figures 1–3, 5–6, and 8 are available on the Acta Orthopaedica website (www.actaorthop.org), identification no. 9338.

JM: acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript and critical revision; final approval of the version to be published. EV and RN: conception and design of the study; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript and critical revision; final approval of the version to be published. BK: acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; final approval of the version to be published. PV and MF: acquisition and analysis of data; final approval of the version to be published.

This study was partially funded by a grant from Biomet. No competing interests have been declared.

- (LROI) D A R. Insight into Quality & Safety: Annual Report of the Dutch Arthroplasty Register (Landelijke Registratie Orthopedische Implantaten) 2013. Insight into Quality & Safety: Annual Report of the Dutch Arthroplasty Register (Landelijke Registratie Orthopedische Implantaten) 2013. Netherlands Orthopaedic Association: ’s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands; 2013; 80.

- Alsema R, Deutman R, Mulder T J. Stanmore total hip replacement. A 15- to 16-year clinical and radiographic follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1994; 76 (2): 240–4.

- Barrack R L, Mulroy R D, Jr., Harris W H. Improved cementing techniques and femoral component loosening in young patients with hip arthroplasty. A 12-year radiographic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1992; 74 (3): 385–9.

- Crowder M J, Hand D J. Analysis of repeated measures. Chapman and Hall, London 1990.

- Emery D, Britton A, Clarke H, Grover M. The Stanmore total hip arthroplasty. A 15- to 20-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty 1997; 12 (7): 728–35.

- Espehaug B, Furnes O, Havelin L I, Engesaeter L B, Vollset S E. The type of cement and failure of total hip replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84 (6): 832–8.

- Garellick G, Rogmark C, Kärrholm J, Rolfson O. Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register, Annual Report 2012: 61–81.

- Gerritsma-Bleeker C L, Deutman R, Mulder T J, Steinberg J D. The Stanmore total hip replacement. A 22-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000; 82 (1): 97–102.

- Gravius S, Wirtz D C, Marx R, Maus U, Andereya S, Muller-Rath R, Mumme T. [Mechanical in vitro testing of fifteen commercial bone cements based on polymethylmethacrylate]. Z Orthop Unfall 2007; 145 (5): 579–85.

- Gruen T A, McNeice G M, Amstutz H C. “Modes of failure” of cemented stem-type femoral components: a radiographic analysis of loosening. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1979; (141): 17–27.

- Hallan G, Aamodt A, Furnes O, Skredderstuen A, Haugan K, Havelin L I. Palamed G compared with Palacos R with gentamicin in Charnley total hip replacement. A randomised, radiostereometric study of 60 HIPS. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2006; 88 (9): 1143–8.

- Hardinge K. The direct lateral approach to the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1982; 64 (1): 17–9.

- Havelin L I, Espehaug B, Vollset S E, Engesaeter L B. The effect of the type of cement on early revision of Charnley total hip prostheses. A review of eight thousand five hundred and seventy-nine primary arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995; 77 (10): 1543–50.

- ISO/TC 150 Committee (Implants for surgery S S, Bone and joint replacement). ISO 16087: 2013 (E). In: Implants for surgery — Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis for the assessment of migration of orthopaedic implants ISO 16087: 2013 (E). Switzerland; 2013.

- Johnston R C, Fitzgerald R H, Jr., Harris W H, Poss R, Muller M E, Sledge C B. Clinical and radiographic evaluation of total hip replacement. A standard system of terminology for reporting results. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990; 72 (2): 161–8.

- Kaptein B L, Valstar E R, Stoel B C, Reiber H C, Nelissen R G. Clinical validation of model-based RSA for a total knee prosthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007; 464: 205–9.

- Karrholm J, Borssen B, Lowenhielm G, Snorrason F. Does early micromotion of femoral stem prostheses matter? 4-7-year stereoradiographic follow-up of 84 cemented prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1994; 76 (6): 912–7.

- Karrholm J, Herberts P, Hultmark P, Malchau H, Nivbrant B, Thanner J. Radiostereometry of hip prostheses. Review of methodology and clinical results. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1997; (344): 94–110.

- Kienapfel H, Hildebrand R, Neumann T, Specht R, Koller M, Celik I, Mueller H H, Griss P, Klose K J, Georg C. The effect of Palamed G bone cement on early migration of tibial components in total knee arthroplasty. Inflamm Res 2004; 53Suppl2: S159–S63.

- Kobayashi A, Donnelly W J, Scott G, Freeman M A. Early radiological observations may predict the long-term survival of femoral hip prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1997; 79 (4): 583–9.

- Malchau H. On the importance of stepwise introduction of new hip implant technology. Assessment of total hip replacement using clinical evaluation, radiostereometry, digitised radiography and a national hip registry. On the importance of stepwise introduction of new hip implant technology. Assessment of total hip replacement using clinical evaluation, radiostereometry, digitised radiography and a national hip registry. Göteborg University: Göteborg; 1995.

- Malchau H, Karrholm J, Wang Y X, Herberts P. Accuracy of migration analysis in hip arthroplasty. Digitized and conventional radiography, compared to radiostereometry in 51 patients. Acta orthopaedica Scandinavica 1995; 66 (5): 418–24.

- Mjoberg B, Rydholm A, Selvik G, Onnerfalt R. Low- versus high-viscosity bone cement. Fixation of hip prostheses analyzed by roentgen stereophotogrammetry. Acta orthopaedica Scandinavica 1987; 58 (2): 106–8.

- Nieuwenhuijse M J, Valstar E R, Kaptein B L, Nelissen R G. The Exeter femoral stem continues to migrate during its first decade after implantation: 10-12 years of follow-up with radiostereometric analysis (RSA). Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (2): 129–34.

- Prins A H, Kaptein B L, Stoel B C, Nelissen R G, Reiber J H, Valstar E R. Handling modular hip implants in model-based RSA: combined stem-head models. J Biomech 2008; 41 (14): 2912–7.

- Ranstam J, Ryd L, Onsten I. Accurate accuracy assessment: review of basic principles. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71 (1): 106–8.

- Ryd L, Albrektsson B E, Carlsson L, Dansgard F, Herberts P, Lindstrand A, Regner L, Toksvig-Larsen S. Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis as a predictor of mechanical loosening of knee prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1995; 77 (3): 377–83.

- Selvik G. Roentgen stereophotogrammetry. A method for the study of the kinematics of the skeletal system. Acta Orthop Scand 1989; Suppl 232: 1–51.

- Valstar E R, Gill R, Ryd L, Flivik G, Borlin N, Karrholm J. Guidelines for standardization of radiostereometry (RSA) of implants. Acta Orthop 2005; 76 (4): 563–72.

- van Steenbergen L N, Denissen G A, Spooren A, van Rooden S M, van Oosterhout F J, Morrenhof J W, Nelissen R G. More than 95% completeness of reported procedures in the population-based Dutch Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (4): 498–505.