Abstract

Background and purpose — Tenosynovial giant cell tumors (t-GCTs) can behave aggressively locally and affect joint function and quality of life. The role of arthroplasty in the treatment of t-GCT is uncertain. We report the results of arthroplasty in t-GCT patients.

Patients and methods — t-GCT patients (12 knee, 5 hip) received an arthroplasty between 1985 and 2015. Indication for arthroplasty, recurrences, complications, quality of life, and functional scores were evaluated after a mean follow-up time of 5.5 (0.2–15) years.

Results — 2 patients had recurrent disease. 2 other patients had implant loosening. Functional scores showed poor results in almost half of the knee patients. 4 of the hip patients scored excellent and 1 scored fair. Quality of life was reduced in 1 or more subscales for 2 hip patients and for 5 knee patients.

Interpretation — In t-GCT patients with extensive disease or osteoarthritis, joint arthroplasty is an additional treatment option. However, recurrences, implant loosening, and other complications do occur, even after several years.

Tenosynovial giant cell tumors (t-GCTs) are benign proliferative growths of the synovial membrane (de saint Aubain Somerhausen and van de Rijn Citation2013). The approximate annual incidence in the USA is 1.8 patients per million inhabitants (Verspoor et al. Citation2013). T-GCT mainly affects adults between 20 and 50 years of age, with the same prevalence in both sexes. There is a predilection for weight-bearing extremities, the knee and the hip being the most commonly involved (Verspoor et al. Citation2014).

The clinical presentation is non-specific, with mild discomfort, stiffness, effusion, or progressive pain. Based on the clinical and radiological presentation, 2 subtypes of t-GCT have been identified, localized t-GCT (Lt-GCT) and diffuse t-GCT (Dt-GCT) (Murphey et al. Citation2008, Verspoor et al. Citation2014).

Treatment strategies are based on removal of all pathological tissue. In primary, limited disease, a surgical synovectomy is often sufficient (Verspoor et al. Citation2013). However, for extensive or recurrent disease, complete surgical synovectomy can be a technical challenge. Recurrence rates have been reported to be between 0% and 15% for Lt-GCT and between 9% and 46% for Dt-GCT, depending on the duration of follow-up and on the joint involved (Chiari et al. Citation2006, Dines et al. Citation2007, Verspoor et al. Citation2014).

A variety of treatment modalities in addition to surgical resection of t-GCT have been used to achieve cure, such as external beam radiation therapy, radiation synovectomy, cryosurgery, immune or targeted therapy, and joint arthroplasty. However, little is known about the actual effect of these additional treatments (Verspoor et al. Citation2013).

The surgical removal of t-GCT combined with arthroplasty has been described previously in patients with extensive disease, and in patients with destructive joint changes caused by the disease itself or by the multiple treatments patients received (Hamlin et al. Citation1998). The goal of this treatment is to achieve a disease-free, well-functioning joint (Flandry et al. Citation1989). In addition, patients with osteoarthritis-like symptoms in whom t-GCT was an incidental finding during arthroplasty have been described (Della Valle et al. Citation2001).

This retrospective study was conducted to analyze the results of arthroplasty in patients with t-GCT. More specifically, we examined the indications, number of recurrences, complications, quality of life, and joint function in relation to t-GCT subtype and the joint affected.

Patients and methods

For this retrospective study, we identified 141 t-GCT patients in our patient databases (1985–2015). 48 patients were classified as Lt-GCT and 93 as Dt-GCT. 17 of these patients (5 Lt-GCT and 12 Dt-GCT) received an arthroplasty ( and ).

Table 1. Details of t-GCT patients treated with arthroplasty: demographics, indications, recurrences, and length of follow-upTable Footnotea

Table 2. All the treatments t-GCT patients received before and after arthroplasty, including complications and implant information

Clinical, pathological, radiological, treatment, and follow-up information were assessed by 2 independent reviewers (FGMV and AS). Any disagreements were resolved by consensus with a third reviewer (HWBS). Recurrences, treatment complications, functional scores, and quality of life (QoL) were documented according to t-GCT subtype and location. During the regular hospital visits, QoL questionnaires were used and function scores were taken.

QoL was evaluated by using the Dutch translation of a generic QoL instrument, the 36-item Short Form health survey (SF-36) (VanderZee et al. Citation1996) and the 20-item Checklist Individual Strength (CIS20r) questionnaire (Vercoulen et al. Citation1999). 14 patients participated, and the other 3 patients were lost to follow-up. 1 patient did not complete all the questions in the CIS20r questionnaire, so it could not be used.

Scoring systems used to evaluate function were the standardized Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) (Bellamy et al. 1988), the Knee Society score (KSS) (Insall Citation1988), and the Harris hip score (HHS) (Garellick et al. Citation1998). The data were extracted from database records. We managed to collect function scores from all but 1 patient.

Ethics

The study protocol (2012/555) was assessed by our institutional review board (the research ethics committee of the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre) and was carried out in the Netherlands in accordance with the applicable rules concerning the review of research ethics committees.

Results

Hip

5 patients received a hip arthroplasty. 4 had Dt-GCT and 1 had Lt-GCT. 2 were women aged 20 and 25 years and 3 were men aged 36, 44, and 49 years. The indication for total hip arthroplasty (THA) was extensive disease (n = 3) and secondary osteoarthritis (n = 1). In the fifth patient, Lt-GCT was an incidental finding. The mean overall follow-up after arthroplasty was 8.6 (7–15) years ().

3 primary patients received their arthroplasty within 1.5 years of diagnosis (). 1 patient with recurrent disease had a surgical synovectomy followed by an unsuccessful yttrium radiosynovectomy elsewhere. 4 years after diagnosis, this patient was treated at our tertiary center using a 3-stage procedure. During almost 15 years of follow-up, no recurrences or complications occurred ( and ).

Another patient who was initially treated using a 3-stage procedure for extensive disease () first had an anterior luxation immediately after THA with acetabular bone impaction grafting, followed by a cup revision after a trauma 5 years later (without any evidence of recurrent disease), and finally had histologically proven recurrent disease 4 years after that. This recurrent disease was treated with a synovectomy, additional cryosurgery, and removal of osteosynthesis material that had been placed during the initial THA ().

Quality of life

An SF-36 score was obtained for 4 of the 5 patients, on average 10 (6–15) years after arthroplasty. 2 patients scored low (> 1 SD below the means for the general population (VanderZee et al. Citation1996)) on Vitality and General health perception and 1 of these 2 patients also scored low on Physical functioning, Social functioning, Role limitations due to physical problems, General mental health, and Bodily pain (Table 3, see Supplementary data).

CIS20r was obtained for 4 patients, on average 10 (6–15) years after arthroplasty. Compared to healthy individuals (Vercoulen et al. Citation1999), 1 patient scored high (> 1 SD above healthy individual means) on all 4 domains: Fatigue, Concentration, Motivation, and Physical activity (Table 4, see Supplementary data).

Function scores

A Harris hip score was obtained for all 5 THA patients, on average 6.8 (4–13) years after arthroplasty. 4 patients scored excellent (90–99) and 1 patient scored fair (77) (Table 5, see Supplementary data).

Knee

12 patients, 4 with Lt-GCT and 8 with Dt-GCT, received a knee arthroplasty, 6 women (mean age 58 (48–63) years) and 6 men (mean age 54 (33–73) years). Indications for arthroplasty were extensive disease (n = 6), secondary osteoarthritis (n = 3), and an incidental finding (n = 3) ( and ). The mean overall follow-up period after arthroplasty was 5.5 (0.2–13) years ().

Patient 7 (Lt-GCT) received a total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for osteoarthritis almost 7 years after diagnosis of t-GCT. Rehabilitation was complicated by stiffness, which was treated by manipulation under anesthesia. 2 other patients with osteoarthritis received a TKA, 8 and 38 years after diagnosis of Dt-GCT.

The 6 patients who were treated for extensive disease received an arthroplasty on average 9 (1.6–17) years after diagnosis (). These patients had 0–4 recurrences before arthroplasty and 1 recurrence diagnosed by ultrasound after TKA with so far no intervention. 2 patients suffered postoperative complications after TKA. 1 patient had neuropathic pain, which was treated with surgical neurolysis (). Another patient experienced stiffness, which was treated by manipulation under anesthesia. This last patient also developed medial tibial component loosening 6 years after arthroplasty, followed by revision surgery. No recurrent disease, polyethylene wear, or infection was found.

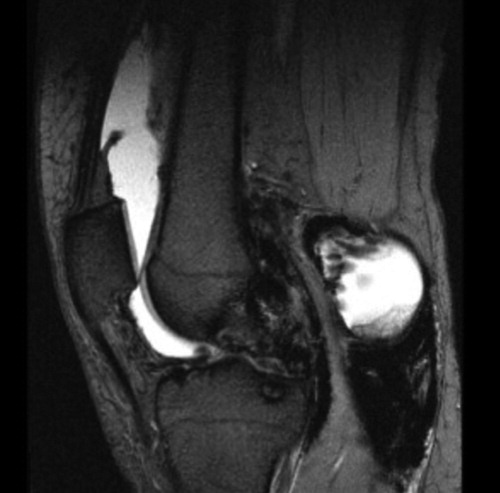

Figure 1. Gradient-echo-based MRI image from a patient with recurrent t-GCT (right knee). There was very low signal intensity corresponding to hemosiderin depositions anterior to the lateral meniscus, extending to the infrapatellar fat pad. Furthermore, there was a hemosiderin deposition in the recessus lateralis posterior to the lateral femoral condyle. These localizations corresponded to recurrent Dt-GCT, which was confirmed by surgical removal.

Quality of life

SF-36 was obtained for 10 patients, on average 4.6 (0.2–11) years after arthroplasty. 5 patients scored low (> 1 SD below the means for the general population) on General health perception; 4 on Physical functioning, Role limitations due to physical problems, Vitality, and Health change; 3 on Social functioning, General mental health, and Bodily pain; and 2 on Role limitations due to emotional problems (Table 3, see Supplementary data).

CIS20r was obtained for 9 of the patients, on average 4.6 (0.2–11) years after arthroplasty. Compared to healthy individuals (Vercoulen et al. Citation1999), 2 patients scored high (> 1 SD above the means for healthy individuals) in all 4 domains, i.e. Fatigue, Concentration, Motivation, and Physical activity, and 1 patient scored high on the Motivation and Physical domains (Table 4, see Supplementary data).

Function scores

WOMAC (Bellamy et al. 1988) and KSS (Insall Citation1988) were obtained for all but 1 patient, at an average of 3.7 (0.2–11) years after arthroplasty. According to the standardized WOMAC sum scores (0–100), higher values indicate less pain, less stiffness, or better physical functioning (Roorda et al. Citation2004). 2 knee patients scored below 50 on all subscales. 3 other knee patients had less than 70 in the total score; in particular, they had low scores on the Stiffness and Physical functioning subscales. On the KSS Object knee score, 7 patients had excellent results (80–100), 1 had good results (70–79), and 3 had poor results (< 60). On the KSS Function knee score, 6 patients had excellent results (80–100) and the other 5 patients had poor results (< 60), as with the low WOMAC scores in these 5 patients (Table 6, see Supplementary data).

Discussion

Indications

In this study, t-GCT patients with extensive disease and/or degenerative joint disease following treatment(s) were eligible for arthroplasty. Also, there were patients who were preoperatively assumed to have osteoarthritis which (during operation) turned out to be t-GCT. Other authors have found similar indications for arthroplasty in t-GCT patients (Bunting et al. Citation2007, Lawrence et al. Citation1999, Murphey et al. Citation2008). Furthermore, unusual cases of t-GCT first presenting after TKA have been described (Bunting et al. Citation2007, Ma et al. Citation2013).

In general, patients with t-GCT in the hip received their arthroplasty over 20 years earlier than patients with t-GCT of the knee. An explanation for this age difference might be that lesions involving the hip joint are associated with a higher incidence of bony erosion and cyst formation compared to those involving the knee. Some investigators have hypothesized that the smaller intra-articular space in the hip does not allow the tumor to expand without causing increased pressure on the femoral and acetabular cartilage (Verspoor et al. Citation2013).

THA has been performed in young patients, with good results. However, the authors of a long-term follow-up evaluation of THA advised caution with this procedure in younger patients because of high failure rates (de Kam et al. Citation2011).

Recurrences

2 recurrences were found in our patient group; both of these Dt-GCT patients were treated for extensive disease. The recurrence after THA was histologically proven. The recurrence after knee arthroplasty was diagnosed and followed on ultrasound. There have been case reports of recurrent t-GCT being diagnosed with arthroscopy or during revision arthroplasty (Ma et al. Citation2011). However, with the improved visualization of periprosthetic soft tissues on MRI, diagnosis of recurrent t-GCT after total joint arthroplasty should no longer be a difficulty (Friedman et al. Citation2013).

Gitelis et al. (Citation1989) reported on 28 patients in whom synovectomy was combined with hip arthroplasty (15 cup arthroplasties, 10 THAs, and 3 hemiarthroplasties—1 of which was subsequently converted to a THA). The average follow-up time was 3.6 years, with 1 recurrence.

In our study, the 2 recurrences occurred 6 and 9 years after arthroplasty, indicating that the number of recurrences may increase further with longer follow-up times. These 2 patients with recurrent disease had a staged procedure before arthroplasty. In hip arthroplasty, clearance of diseased tissue was done before implantation, to minimize the chance of recurrent disease. However, 1 of the 2 hip patients who underwent a staged procedure showed recurrent disease. A meta-analysis of t-GCT in hips showed a recurrence rate of 4% with surgical synovectomy and total joint arthroplasty as compared to a rate of 28–50% after treatment with surgical synovectomy alone. The indication for additional arthroplasty depended on the extent of disease and on cartilage damage (Della Valle et al. Citation2001).

With extensive Dt-GCT, extra-articular lesions are often encountered, e.g. in the head of one of the gastrocnemius muscles (). In these cases, all pathological tissue should be removed before joint arthroplasty, to reduce the risk of residual and/or recurrent disease. To ensure removal of all pathological tissue, before arthroplasty a staged procedure should be considered in these difficult-to-cure patients.

Complications

We had 2 cases of aseptic loosening 5 and 6 years after arthroplasty, but not recurrent disease. Hamlin et al. (Citation1998) described 18 patients who underwent TKA, 14 with Dt-GCT and 4 with Lt-GCT. There were 3 cases of aseptic loosening, 1 of them with recurrent disease. Another patient with recurrent disease needed an above-the-knee amputation.

Other complications, such as stiffness requiring manipulation and neuropathic pain requiring neurolysis, have been reported in patients undergoing arthroplasty (Healy et al. Citation2013). However, this patient group is possibly more prone to develop these kinds of complications from limited joint function preoperatively, due to the disease itself or to previously received treatments (Verspoor et al. Citation2014).

Quality of life

In 5 patients, we found reduced QoL scores compared to the general population (VanderZee et al. Citation1996). Recently, 2 other publications had QoL scores for t-GCT patients (van der Heijden et al. Citation2014, Verspoor et al. Citation2014) but these scores were not reported for t-GCT patients treated with arthroplasty.

Joint function

We found reduced joint function after arthroplasty in 5 of the 12 t-GCT knee patients, mainly due to stiffness (Table 6, see Supplementary data). It has been reported that preoperative joint function is a predictor of postoperative TKA function (Jones et al. Citation2003). In general, reduced preoperative joint function in t-GCT patients is related to disease severity or the often multiple treatments in the past (Chiari et al. Citation2006). Similar results have been reported for postoperative hip function (Fortina et al. Citation2005). However, 4 out of 5 of our hip arthroplasty patients had excellent Harris hip scores. Gitelis et al. (Citation1989) reported that after an average follow-up of 5 years, 24 of 28 patients treated with primary hip arthroplasty had satisfactory results and 4 had poor results. The poor results were due to mechanical failure of the implants (Gitelis et al. Citation1989).

Our hip arthroplasty patients had better function scores than our knee patients, which might be explained by their younger age and shorter course of disease. Taking disease-induced loss of joint function into consideration, joint function outcomes may be better with earlier joint arthroplasty. It may also reduce the chances of recurrent t-GCT, as the disease is less extensive and therefore easier to eradicate. However, early joint arthroplasty might result in higher revision rates.

Limitations

The retrospective character of this study, the small number of patients, the different indications for arthroplasty, and the different implants used should not go unnoticed. It is difficult to perform a prospective study with adequate patient numbers, because of the low incidence of t-GCT and the years of delay before local recurrence may occur. Complete information regarding subtypes, location, arthroplasty, and other treatments was available, including long-term follow-up. Because of this, the information could possibly be used in future (meta-)analyses to obtain evidence regarding arthroplasty in the treatment of t-GCT. Furthermore, patients with localized t-GCT as an incidental finding should be differentiated from those with diffuse recurrent and extensive t-GCT, as localized disease behaves less aggressively.

It should also be noticed that QoL and function scores were taken at variable points after arthroplasty. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report QoL measures in t-GCT patients who underwent arthroplasty. QoL is important in a disease as disabling as t-GCT. Further studies should investigate whether or not the reduced QoL in this specific patient group is a consequence of the disease itself, of the arthroplasty, of the (multiple) treatment(s) received, or of other factors, such as comorbidities or issues not related to disease.

In summary, in t-GCT patients with extensive disease or osteoarthritis, arthroplasty is an additional treatment option after surgical synovectomy. However, recurrences, implant loosening, and other complications do occur, even after years of follow-up.

Supplementary data

Tables 3–6 are available on the website of Acta Orthopaedica at www.actaorthop.org, identification number 10006.

The study concept and design were developed by FGMV and HWBS. AS and FGMV carried out the data acquisition. The quality control of data and algorithms was by FGMV and GH. FGMV and GH performed the data analysis and interpreted the results. The manuscript preparation and editing was done by FGMV. All the authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

Bellamy N, Buchanan W W, Goldsmith C H, Campbell J, Stitt L W. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol 1988; 15 (12): 1833-40.

- Bunting D, Kampa R, Pattison R. An unusual case of pigmented villonodular synovitis after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2007; 22 (8): 1229–31.

- Chiari C, Pirich C, Brannath W, Kotz R, Trieb K. What affects the recurrence and clinical outcome of pigmented villonodular synovitis? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 450: 172–8.

- de Kam D C, Busch V J, Veth R P, Schreurs B W. Total hip arthroplasties in young patients under 50 years: limited evidence for current trends. A descriptive literature review. Hip Int 2011; 21 (5): 518–25.

- de saint Aubain Somerhausen N, van de Rijn M. Tenosynovial giant cell tumour, diffuse/localized type. In: Fletcher C D, Bridge J A, Hogedoorn P C, Mertens F, eds. WHO classification of tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone 2013; 5 (4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press).

- Della Valle A G, Piccaluga F, Potter H G, Salvati E A, Pusso R. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the hip: 2- to 23-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001; (388): 187–99.

- Dines J S, DeBerardino T M, Wells J L, Dodson C C, Shindle M, DiCarlo E F, et al. Long-term follow-up of surgically treated localized pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee. Arthroscopy 2007; 23 (9): 930–7.

- Flandry F, McCann S B, Hughston J C, Kurtz D M. Roentgenographic findings in pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989; (247): 208–19.

- Fortina M, Carta S, Gambera D, Crainz E, Ferrata P, Maniscalco P. Recovery of physical function and patient’s satisfaction after total hip replacement (THR) surgery supported by a tailored guide-book. Acta Biomed 2005; 76 (3): 152–6.

- Friedman T, Chen T, Chang A. MRI diagnosis of recurrent pigmented villonodular synovitis following total joint arthroplasty. HSS J 2013; 9 (1): 100–5.

- Garellick G, Malchau H, Herberts P. Specific or general health outcome measures in the evaluation of total hip replacement. A comparison between the Harris hip score and the Nottingham Health Profile. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1998; 80 (4): 600–6.

- Gitelis S, Heligman D, Morton T. The treatment of pigmented villonodular synovitis of the hip. A case report and literature review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989; (239): 154–60.

- Hamlin B R, Duffy G P, Trousdale R T, Morrey B F. Total knee arthroplasty in patients who have pigmented villonodular synovitis. J Bone Joint Surg 1998; 80 (1): 76–82.

- Healy W L, Della Valle C J, Iorio R, Berend K R, Cushner F D, Dalury D F, et al. Complications of total knee arthroplasty: standardized list and definitions of the Knee Society. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471 (1): 215–20.

- Insall J N. Presidential address to The Knee Society. Choices and compromises in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988; (226): 43–8.

- Jones C A, Voaklander D C, Suarez-Alma M E. Determinants of function after total knee arthroplasty. Phys Ther 2003; 83 (8): 696–706.

- Lawrence T, Moskal J T, Diduch D R. Analysis of routine histological evaluation of tissues removed during primary hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg 1999; 81 (7): 926–31.

- Ma X, Xia C, Wang L, Zhao L, Liu H, He J. An Unusual Case of Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis 14 Years After Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26 (2): 339.e5–e6.

- Ma X, Shi G, Xia C, Liu H, He J, Jin W. Pigmented villonodular synovitis: a retrospective study of seventy five cases (eighty one joints). Int Orthop 2013; 37 (6): 1165–70.

- Murphey M D, Rhee J H, Lewis R B, Fanburg-Smith J C, Flemming D J, Walker E A. Pigmented villonodular synovitis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2008; 28 (5): 1493–518.

- Roorda L D, Jones C A, Waltz M, Lankhorst G J, Bouter L M, van der Eijken J W, et al. Satisfactory cross cultural equivalence of the Dutch WOMAC in patients with hip osteoarthritis waiting for arthroplasty. Ann Rheum Dis 2004; 63 (1): 36–42.

- van der Heijden L, Mastboom M J, Dijkstra P D, van de Sande M A. Functional outcome and quality of life after the surgical treatment for diffuse-type giant-cell tumour around the knee: a retrospective analysis of 30 patients. Bone Joint J 2014; 96-B (8): 1111–8.

- VanderZee K I, Sanderman R, Heyink J W, de Haes H. Psychometric qualities of the RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0: a multidimensional measure of general health status. Int J Behav Med 1996; 3 (2): 104–22.

- Vercoulen J H M, Alberts M, Bleijenberg G. The Checklist Individual Strength (CIS). Gedragstherapie 1999; 32: 131–6.

- Verspoor F G, van der Geest I C, Vegt E, Veth R P, van der Graaf W T, Schreuder H W. Pigmented villonodular synovitis: current concepts about diagnosis and management. Future Oncol 2013; 9 (10): 1515–31.

- Verspoor F G, Zee A A, Hannink G, van der Geest I C, Veth R P, Schreuder H W. Long-term follow-up results of primary and recurrent pigmented villonodular synovitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014; 53 (11): 2063–70.