Abstract

Background and purpose — Total knee replacement (TKR) in younger patients using cemented components has shown inferior results, mainly due to aseptic loosening. Excellent clinical results have been reported with components made of trabecular metal (TM). In a previous report, we have shown stabilization of the TM tibial implants for up to 5 years. In this study, we compared the clinical and RSA results of these uncemented implants with those of cemented implants.

Patients and methods — 41 patients (47 knees) aged ≤ 60 years underwent TKR. 22 patients (26 knees) received an uncemented monoblock cruciate-retaining (CR) tibial component (TM) and 19 patients (21 knees) received a cemented NexGen Option CR tibial component. Follow-up examination was done at 10 years, and 16 patients (19 knees) with TM tibial components and 17 patients (18 knees) with cemented tibial components remained for analysis.

Results — 1 of 19 TM implants was revised for infection, 2 of 18 cemented components were revised for knee instability, and no revisions were done for loosening. Both types of tibial components migrated in the first 3 months, the TM group to a greater extent than the cemented group. After 3 months, both groups were stable during the next 10 years.

Interpretation — The patterns of migration for uncemented TM implants and cemented tibial implants over the first 10 years indicate that they have a good long-term prognosis regarding fixation

The incidence of total knee replacement (TKR) in younger patients has increased dramatically in the last decades (W-Dahl et al. Citation2010, Leskinen et al. Citation2012). However, the results of TKR in this group of active patients are inferior (Julin et al. Citation2010, W-Dahl et al. Citation2010), which is often due to aseptic loosening (Harrysson et al. Citation2004, Julin et al. Citation2010, Odland et al. Citation2011). Radiostereometric analysis (RSA) studies have shown continuous migration of the tibial implant in cemented TKRs, indicating bone resorption under the implant and suggesting that there is an unstable interface (Carlsson et al. Citation2005, Nilsson et al. Citation2006). Such continuous migration has not been found in uncemented implants coated with hydroxyapatite (Carlsson et al. Citation2005, Nilsson et al. Citation2006, Molt and Toksvig-Larsen Citation2014).

Trabecular metal (TM) has several theoretical advantages. Bony ingrowth and sufficient biological fixation have been shown in animal studies (Bullens et al. Citation2010, Rahbek et al. Citation2005) and also in retrieved human specimens (D’Angelo et al. Citation2008, Sambaziotis et al. Citation2012). Excellent cellular adherence, growth, and differentiation of osteocytes to the TM surface was found by Balla et al. (Citation2010) and Sagomonyants et al. (2011).

Numerous studies using TM tibial components have shown excellent clinical results after 5–8 years of follow-up (Kamath et al. Citation2011, Ghalayini et al. Citation2012, Fernandez-Fairen et al. Citation2013, Niemeläinen et al. Citation2014, Hayakawa et al. Citation2014, Pulido et al. Citation2015). There were no revisions for aseptic loosening of the tibial component in any of these studies.

We have previously presented the 2-year (Henricson et al. Citation2008) and the 5-year results (Henricson et al. Citation2013) of an RSA study comparing uncemented TM CR monoblock tibial components with cemented NexGen CR tibial components in patients less than 60 years of age. These studies showed that after an initial settling over the first 3 months, both the TM implants and the cemented tibial implants stabilized up to 2 years and that the stability was maintained up to 5 years postoperatively. We concluded that this migratory pattern was possibly a good sign concerning long-term fixation, but emphasized the need for longer follow-up. We continued the follow-up of these patient cohorts, and now report the results after 10 years.

Patients and methods

This study was originally designed as a randomized clinical trial comparing uncemented monoblock TM tibial components with cemented modular tibial components of the NexGen Option cruciate-retaining (CR) design (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN). For logistical reasons, this was changed to a comparison of 2 consecutive series of patients who were operated in succession by a single surgeon, first operating the TM implants and immediately afterwards the cemented ones (Henricson et al. Citation2008).

Inclusion criteria were primary or secondary osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee with symptoms warranting surgery, age below 60 years, and weight below 120 kg. Consecutive eligible patients on the waiting list at Falu General Hospital were asked to participate, and all of them agreed. The TM implants were inserted first (from May 2003 to April 2004) in 22 patients (26 knees), and the cemented implants were inserted thereafter (from September 2004 to February 2005) in 19 patients (21 knees). 6 patients had simultaneous bilateral knee arthroplasty: 4 were operated with bilateral TM implants (8 knees), and 2 received bilateral cemented implants (4 knees) (). The femoral component was either cemented or uncemented (according to randomization), which has been the subject of another study (Gao et al. Citation2009).

Table 1. Flow chart of the patients

The posterior cruciate ligament was retained in all cases but balanced when needed. An all-polyethylene patellar component was used when the osteoarthritic disease had produced a concave patellar articular surface (3 patients in each group).

For the RSA analysis, 6 tantalum markers were inserted into the polyethylene of the monoblock TM implant. To eliminate potential errors of measuring modular polyethylene component motion in relation to the metal tray in the cemented implants, the tibial tray was equipped by the supplier with 5 tantalum markers encased in titanium rods attached to the underside of the titanium tibial component (n = 4) and at the tip of the stem (n = 1). Thus, in the cemented implants tantalum markers in the polyethylene were not used for analysis. In all knees, 9 tantalum markers were spread out in the metaphysis of the tibia.

The initial RSA examinations were performed a mean of 4 (2–7) days after the operation. Subsequent examinations were done at 6 weeks, at 3, 12, and 24 months, and at 5 years (Henricson et al. Citation2013). The 10-year examinations described here were performed in December 2014 and January 2015. The patients were examined supine using a biplanar calibration cage (Cage 10; RSA Biomedical, Umeå, Sweden). At the first reference examination, the knee was positioned with its anatomical axes parallel to the cardinal axes of the calibration cage.

RSA was performed using UmRSA software (version 6.0; RSA Biomedical) according to a technique described previously (Henricson et al. Citation2008, Citation2013).

The relative movements of the tibial component in relation to bone were measured using the markers in the tibial metaphysis as the fixed reference segment. The rotations were expressed about the transverse, longitudinal, and sagittal axes of the knee. In order to ensure identical points of measurement for the translations in different knees, standardized positions at the periphery of the tibial tray were constructed as previously described (Nilsson et al. Citation1991). Translations were expressed as the maximum total point motion (MTPM) (Ryd Citation1986), subsidence, and lift-off. In each implant, the largest negative value for translation of the standardized positions along the y-axis was called maximum subsidence, and the largest positive y-translation was called lift-off. These movements were measured with both the postoperative investigation and the 3-month investigation as reference.

At least 5 different methods have been published proposing to indicate the prognostic value of RSA. To test the value of these methods, we performed the following analyses, which will be referred to as analyses I-V.

We calculated the change in MTPM between 1 and 2 years (analysis I), and between 2 and 5 years (analysis II). An increase in MTPM of more than 0.2 mm between the first and second year, and of more than 0.3 mm between the second and fifth year has been considered to be continuous migration according to the definition (modified continuous migration, MCM) established by Ryd et al. (Citation1995) and used by Wilson et al. (Citation2012).

We calculated the rate of migration (MTPM) per year up to 2 years (analysis III) with the postoperative examination as reference, according to Pijls et al. (Citation2012b). In their paper, the migration between postoperatively and 6 months, between 6 months and 1 year, and between 1 year and 2 years was calculated. Since there was no 6-month investigation in the present study, the 3-month investigation was used instead.

We calculated the rate of migration (MTPM) per year up to 10 years (analysis IV) with the 1-year examination as reference, according to Pijls et al. (Citation2012a). Finally, the magnitude of MTPM at 12 months with the postoperative examination as reference was determined in every patient (analysis V) (Pijls et al. Citation2012c).

The repeatability of the RSA measurements was calculated using double examination as described by Ranstam et al. (Citation2000). Significant rotations at the 95% significance level were >0.25° (transverse), > 0.26° (longitudinal), and >0.17° (sagittal). Corresponding values for y-translation were >0.11 mm.

Clinical evaluation was performed using the knee score, pain score, and function score of the Knee Society (Insall et al. Citation1989). We also analyzed the presence and size of radiolucent lines as described by the Knee Society (Ewald Citation1989).

Between the previously published 5-year follow-up (Henricson et al. Citation2013) and the present 10-year follow-up, 3 additional patients (5 knees) could not be analyzed. The general health of 1 patient (with 2 TM implants) was too poor for him to attend, and 1 patient (with 1 TM implant) refused to attend. Finally, 1 patient with bilateral cemented NexGen tibias sustained severe ligamentous laxity in both knees after a fall. She underwent several operations and finally received bilateral NexGen RHK revision implants. Her initial implants were found to be firmly fixed to bone at the time of revision ().

Statistics

Since the main interest of the study was the amount and progression of migration, we analyzed only absolute values of parameters for which both negative and positive values were possible (the sign being an indication of the direction of movement).

Since the migration data were not normally distributed (according to the Shapiro-Wilk and Pearson tests for normality), the median and interquartile range are given in the tables. After log transformation of the data, normality was achieved, and mean and 95% CI could be calculated and then re-transformed back to the original scale. These data are given in the tables and figures for easier visual display. For statistical analysis, the median difference and the corresponding 95% CI for the median difference for each migration and clinical parameter were calculated as described by Campbell and Gardner (Citation1988). There was statistical significance between groups when the CI for the median difference did not include 0. In addition, Mann-Whitney U-test was used. For comparison of migration over time, Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. Any p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

For patients with bilateral operations, only the first-operated knee was included in the statistical calculations.

Ethics

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Umeå University (entry no. Um 03-004).

Results

Implant migration

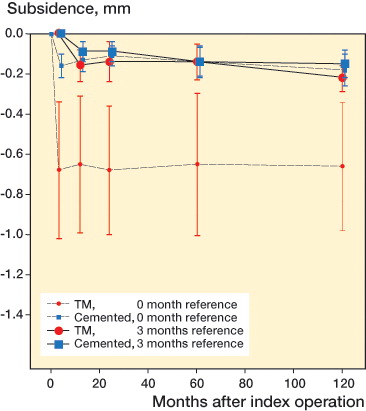

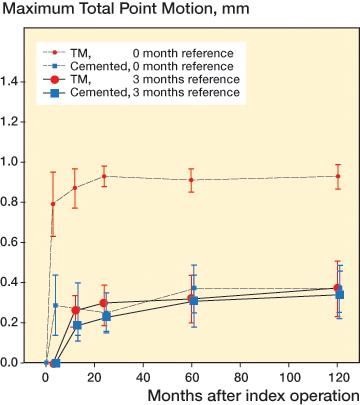

At 10 years, the TM implants showed statistically significantly more rotation around the x- and y-axes, and significantly more translation measured as maximum subsidence and MTPM.In contrast, the NG implants showed greater maximum lift-off, whereas there was no difference between the groups in z- axis rotation ( and Table 3, see Supplementary data). However, as was shown already in the 5-year follow-up (Henricson et al. Citation2013), nearly all migration in both groups occurred within the initial 3 months with stabilization thereafter. We therefore calculated the migration at 10 years using the 3-month examination as reference (). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups except for subsidence: with a median difference in subsidence of 0.10 mm (95% CI: 0.01–0.17; p < 0.02) (, and and ). 1 TM tray showed an MTPM of more than 0.2 mm between 1 and 2 years (Ryd et al. Citation1995). It stabilized thereafter, and showed a change in MTPM between 2 and 5 years of only 0.03 mm, and between 2 and 10 years of 0.07 mm. No TM implants showed a change in MTPM of more than 0.3 mm between 2 and 5 years, or between 2 and 10 years. In the NexGen cemented group, no implants showed MTPM of more than 0.2 mm between 1 and 2 years. One implant had MTPM of more than 0.3 between 2 and 5 years, and 3 implants had MTPM of more than 0.3 mm between 2 and 10 years.

Figure 1. Maximum subsidence of the tibial component in the 2 groups with postoperative and 3-month examinations as reference. Mean with 95% CI (whiskers).

Figure 2. Maximum total point motion (MTPM) of the tibial component in the 2 groups, with postoperative and 3-month examinations as reference. Mean with 95% CI (whiskers).

Table 2. Migration at 10 years with postoperative examination as reference. In patients who were operated bilaterally, only the first-operated knee was included

Table 4. Migration at 10 years with 3-month examination as reference. In patients who were operated bilaterally, only the first-operated knee was included

Table 5. Median differences and 95% CI for migration at 10 years between trabecular metal (TM) and NexGen cemented (NG) tibial components with 3-month examination as reference. In patients who were operated bilaterally, only the first-operated knee was included

Excluding the initial migration over the first 3 months, the annual migration was very low in both groups of implants (Table 6, see Supplementary data). Using the 1-year examination as reference, the TM implants had a mean MTPM of 0.031 (95% CI: –0.10 to 0.16) mm/year, and the NexGen cemented implants had a mean MTPM of 0.032 (95% CI: –0.06 to 0.12) mm/year up to 10 years (ns) (Pijls et al. Citation2012a).

Using the criteria of Pijls et al. (Citation2012c), only 4 out of the 19 TM implants showed acceptable migration (MTPM of <0.5 mm) at 12 months. 10 had a migration at risk (MTPM of between 0.5 and 1.6 mm) and 5 had unacceptable migration (MTPM of >1.6 mm). The corresponding values for the 18 NexGen implants were 12, 6, and 0, respectively.

Radiographic findings

Thin radiolucent lines (< 1 mm) were found in 9 TM knees on the postoperative radiographs. All but 1 had disappeared at 2 years, and the remaining line had also disappeared at 5 years. At 10 years, no radiolucent lines could be detected, and there was seemingly close attachment of the bone to the tibial tray and pegs.

In the cemented NexGen group, thin radiolucent lines (< 1 mm) were found in 10 knees at 2 years. At 5 years, only 5 of these lines could be detected. At 10 years, these lines were only found in 3 knees. The lines were located at the most medial centimeter of the tibial tray, and none of them were progressive.

Clinical findings

At 10 years, there were no statistically significant differences in Knee Society knee score, pain score, and function score between the 2 groups (Table 7, see Supplementary data).

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that the TM implants continued to be firmly fixed to bone for 10 years, with stabilization from 3 months onwards after the early initial migration. This pattern of migration has been shown to indicate a benign interface with possible bony in- or ongrowth (Bellemans Citation1999). In our previous paper on this patient cohort, we concluded that the migration pattern from 3 months to 5 years indicated an excellent result concerning long-term fixation (Henricson et al. Citation2013), and the present results at 10 years corroborate this finding.

One weakness of the study was the small number of patients. However, no implants were revised for loosening and the results at 10 years were similar to those at 5 years. Thus, we do not believe that the small numbers were an important limitation of the study.

In recent years, several clinical studies have shown excellent clinical results for the TM implants in the 5- to 8-year perspective with very few (if any) revisions due to aseptic loosening (Kamath et al. Citation2011, Milchteim and Unger Citation2011, Ghalayini et al. Citation2012, Fernandez et al. 2013, Hayakawa et al. Citation2014, Niemeläinen et al. Citation2014, Pulido et al. Citation2015). The only exception is the study by Meneghini and de Beaubien (Citation2013), who found 9 early loose tibial components in 106 posterior stabilized TM implants, the majority occurring in tall, heavy men. This contrasts with the results from the Finnish Arthroplasty Registry which showed that, although the patients who received TM implants were younger and were more likely to be men (compared to those who received cemented implants), the 7-year survival rate was 100% with revision due to aseptic loosening as endpoint (Niemiläinen et al. 2014). Also, in the Swedish Arthroplasty Registry the risk ratio for revision for the TM implant is lower than that for the cemented NexGen implant, although patients receiving the TM implant are generally younger and more often male (Sundberg et al. Citation2015). Thus, the good long-term clinical results regarding fixation in uncemented total knee arthroplasty appear to be in keeping with the RSA migratory pattern of stabilization after the initial postoperative settling, as found in the present study. This is also in accordance with findings in other studies of both the knee (Grewal et al. Citation1992, Ryd et al. Citation1995, Pijls et al. Citation2012b) and the hip (Ström et al. Citation2006, Terré Citation2010, Wolf et al. Citation2010, Vidalain Citation2011, Callary et al. Citation2012).

The excellent results and a pristine implant-bone interface with no radiolucent lines seen in any TM implants in the present study correspond to what has been reported for the same implant (Milchteim and Unger Citation2011, Kamath et al. Citation2011, Ghalayini et al. Citation2012, Hayakawa et al. Citation2014). This may reflect some specific features of how TM interacts with bone. TM has been found to stimulate the attachment of—and mineralization by—human osteoblasts to a much greater extent than porous Ti controls (Balla et al. Citation2010, Sagomonyants et al. Citation2011). This may be an explanation for the finding of TM having superior bony gap healing properties compared to glass bead-blasted Ti alloy (Rahbek et al. Citation2005). Also, the apparent elastic modulus of trabecular tantalum being close to that of bone may be an advantage, minimizing the teeter-totter behavior usually seen with uncemented titanium or chromium-cobalt tibial trays (Nilsson and Kärrholm Citation1993, Zardiackas et al. Citation2001).

It is well known from other RSA studies that uncemented implants (both hip and knee) show much greater early migration compared to cemented fixation (Nilsson et al. Citation1999, Citation2006, Kärrholm et al. Citation1998, Henricson et al. Citation2008, Wilson et al. Citation2012). There are several reasons for this. Directly after the implantation, the immediate fit between the implant and bone is not perfect. The preparation of the bone bed creates irregularities (Toksvig-Larsen and Ryd Citation1991), and the cutting process generates heat and therefore necrosis of the bone, which will eventually be resorbed (Toksvig-Larsen et al. Citation1990). Also, the bone quality may vary between patients (Li and Nilsson Citation2000). Thus, the uncemented implant will migrate/settle and compress the underlying bone until it is strong enough to support the implant. As these factors vary between patients, the amount of initial migration will also vary, resulting in large dispersion around the mean, as can be seen in this report. Cemented fixation, on the other hand, implies immediate firm fixation of the implant, and the postoperative bone resorption that occurs will be much smaller, with smaller dispersion of the mean. If this difference in initial migration between cemented and uncemented fixation is sufficiently large immediately after surgery, a difference will be apparent even at the 10-year follow-up—even if the uncemented implants are completely stable from 3 months onwards. In the present study, this phenomenon was clearly seen where the magnitude of migration at 10 years was lower for the cemented NexGen implants for all parameters except z-axis rotation, when using the postoperative examination as reference. From this, one can conclude that just comparing the magnitude of migration between different types of fixation is not meaningful, especially when comparing cemented and uncemented fixation.

Measurement of migration in a manner similar to how polyethylene wear in hip arthroplasty cups is measured would be more adequate. In polyethylene wear measurements of hip arthroplasty, the initial “bedding in” can vary considerably between polyethylenes and it is normally judged to be unimportant in terms of wear. Instead, the penetration over time of the femoral head, occurring after the initial “bedding in”, is what is calculated as actual wear. Analogous to that, the magnitude of the initial settling is not as important as the pattern and magnitude of migration over time. The pattern of migration is therefore much more important for analysis of implant fixation than the magnitude of fixation. Stabilization after the initial settling should be interpreted as a good sign concerning long-term fixation, whereas continuous migration is an ominous sign.

Several methods have been proposed to indicate the prognostic value of RSA. Common to most of them is analysis of the magnitude of the change in migration (MTPM) over time as an indicator (Ryd et al. Citation1995, Wilson et al. Citation2012, Pijls et al. Citation2012a,Citationb). By using any of these methods on the present TM material, we can conclude that all of them were able to prognosticate the long-term result, as no implant showed MTPM of >0.3 mm between 2 and 5 years, stabilized between 3 months and 2 years, or had an annual migration rate of only 0.031 mm per year. The magnitude of MTPM at 12 months (Pijls et al. Citation2012c) cannot, however, be used as an indicator of probable future aseptic loosening of uncemented implants. According to this definition, 80% of the TM implants in the present study would have been at risk of late loosening at 10 years.

In summary, the present study shows that the uncemented TM tibial components continue to be stably fixed to the bone for 10 years in younger patients.

Supplementary data

Tables 3, 6, and 7 are available on the website of Acta Orthopaedica (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 10014.

AH performed the surgery, performed the follow-ups, and analyzed the data. KGN initiated the study and analyzed data. Both authors wrote the manuscript.

This study was supported by institutional grants from Zimmer and Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden.

No competing interests declared.

- Balla V K, Bodhak S, Bose S, Bandyopadhyay A. Porous tantalum structures for bone implants: fabrication, mechanical and in vitro biological properties. Acta Biomater 2010; 6: 3349–59.

- Bellemans J. Osseointegration in porous coated knee arthroplasty. The influence of component coating type in sheep. Acta Orthop Scand 1999; (Suppl288):1–35.

- Bullens H J, Screader H W B, de Waal Malefijt M C, Verdonschot N, Buma P. The presence of periosteum is essential for the healing of large diaphyseal segmental defects reconstructed with trabecular metal. A study in the femur of goats. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2010; 92: 24–31.

- Callary S A, Campbell D G, Mercer G E, Nilsson K G, Field J R. The 6-year migration characteristics of a hydroxyapatite-coated femoral stem: a radiostereometric analysis study. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27(7): 1344–48

- Campbell M J, Gardner M J. Calculating confidence intervals for some non-parametric analyses. Br Med J 1988; 256: 1454–6.

- Carlsson Å, Björkman A, Besjakov J, Önsten I. Cemented tibial component fixation performs better than cementless fixation: a randomized study comparing porous-coated, hydroxyapatite-coated and cemented tibial components over 5 years. Acta Orthop 2005; 76: 362–9.

- D’Angelo F, Murena I, Campagnolo M, Zatti G, Cherobino P. Analysis of bone ingrowth on a tantalum cup. Indian J Orthop 2008; 42: 275–8.

- Ewald F C. The Knee Society total knee arthroplasty roentgenographic evaluation and scoring system. Clin Orthop 1989; (248): 9–12.

- Fernandez-Fairen M, Hernández-Vaquero D, Murcia A, Llopis R. Trabecular metal in total knee arthroplasty associated with higher knee scores: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471: 3543–53.

- Gao F, Henricson A, Nilsson K G. Cemented versus uncemented fixation of the femoral component of the NexGen CR total knee replacement in patients younger than 60 years. Knee 2009; 16: 200–6.

- Ghalayini S R A, Helm A T, McLauchlan C J. Minimum 6- year results of an uncemented trabecular metal tibial component in total knee arthroplasty. Knee 2012; 19: 872–4.

- Grewal R, Rimmer M G, Freeman M A R. Early migration of prostheses related to long-term survivorship: Comparison of tibial components in knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1992; 74 (2): 239–42.

- Harrysson O L, Robertsson O, Nayfeh J F. High cumulative revision rate of knee arthroplasties in younger patients with osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; 421: 162–8.

- Hayakawa K, Date H, Tsujimura S, Nojiri S, Yamada H, Nakagawa K. Mid-term results of total knee arthroplasty with a porous tantalum monoblock tibial component. The Knee 2014; 21: 199–203.

- Henricson A, Linder L, Nilsson K G. A trabecular metal component in total knee replacement in patients younger than 60 years. A two-year radiostereophotogrammetric analysis. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008; 90-B (12): 1585–93.

- Henricson A, Rösmark D, Nilsson K G. Trabecular metal tibia still stable at 5 years. An RSA study of 36 patients aged less than 60 years. Acta Orthop 2013; 84(4): 398–405

- Insall J N, Dorr L D, Scott R D, Scott W N. Rational of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop 1989; 248: 13–4.

- Julin J, Jämsen E, Puolakka T, Konttinen Y, Moilanen T. Younger age increases the risk of early prosthesis failure following primary total knee replacement for osteoarthritis. A follow-up study of 32.019 total knee replacements in the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2010;81:413–9.

- Kamath A F, Lee G-C, Sheth N P, Nelson C L, Garino J P, Israelite C L. Prospective results of tantalum monoblock tibia in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26(8): 1390–4.

- Kärrholm J, Freeh W, Nivbrant B, Malchau H, Snorrason F, Herberts P. Fixation and metal release from the Tifit femoral stem prosthesis: 5-year follow-up of 64 cases. Acta Orthop 1998; 69(4): 369–78

- Leskinen J, Eskelinen A, Huhtala H, Paavolainen P, Remes V. The incidence of knee arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis grows rapidly among baby boomers: a population-based study in Finland. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64(2): 423–8.

- Li M G, Nilsson K G. The effect of preoperative bone quality on the fixation of the tibial component in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2000;15(6):744–53.

- Meneghini R M, de Beaubien B C. Early failure of cementless porous tantalum monoblock tibial components. J Arthroplasty 2013; 28: 1505–8.

- Milchteim C, Unger A S. Cementless fixation in high performance knee design. Tech Knee Surg 2011; 10: 136–42.

- Molt M, Toksvig-Larsen S. Peri-apatite enhances prosthetic fixation in a TKA – a prospective randomized RSA study. J Arthritis 2014; 3: 134–9.

- Niemeläinen M, Skyttä E, Remes V, Mäkelä K, Eskelinen A. Total knee arthroplasty with an uncemented trabecular metal component. A registry-based analysis. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29: 57–60.

- Nilsson K G, Kärrholm H. Increased varus-valgus tilting of screw-fixated knee prostheses. Stereoradiographic study of uncemented vs cemented tibial components. J Arthroplasty 1993; 8(5): 529–40.

- Nilsson K G, Kärrhom J, Ekelund L, Magnusson P. Evaluation of micromotion in cemented vs. uncemented knee arthroplasty in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: randomized study using roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis. J Arthroplasty 1991; 6: 265–78.

- Nilsson K G, Kärrholm J, Carlsson L, Dalén T. hydroxyapatite coating versus cemented fixation of the tibial component in total knee arthroplasty. Prospective randomized comparison of hydroxyapatite-coated and cemented tibial components with 5-year follow-up using radiostereometry. J Arthroplasty 1999; 14: 9–20.

- Nilsson K G, Henricson A, Norgren B, Dalén T. Uncemented HA-coated implant is the optimum fixation for TKA in the young patient. Clin Orthop Rel Res 2006; 448: 129–38.

- Odland A N, Callaghan J J, Liu S S, Wells C W. Wear and lysis is the problem in modular TKA in the young OA patient at 10 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011; 469(1): 41–7.

- Pijls B G, Valstar E R, Kaptein B L, Fiocco M, Nelissen R G H H. The beneficial effect of hydroxyapatite lasts. A randomized radiostereometric trial comparing hydroxyapatite-coated, uncoated, and cemented tibial components for up to 16 years. Acta Orthop 2012a; 83(2): 135–41

- Pijls B G, Nieuwenhuijse M J, Schooness J W, Middeldorp S, Valstar E R, Nelissen R G H H. RSA prediction of high failure rate for the uncoated Interax TKA confirmed by metaanalysis. Acta Orthop 2012b; 83(2): 142–7.

- Pijls B G, Valstar E R, Nuota K-A, Plevier J W M, Fiocco M, Middeldorp S, Nelissen R G H H. Early migration of tibial components is associated with late revision. A systemic review and meta-analysis of 21,000 knee arthroplasties. Acta Orthop 2012c; 83(6):614–24.

- Pulido L, Abdel M P, Lewallen D G, Stuart M J, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Hanssen A D, Pagnano M W. Trabecular metal components were durable and reliable in primary total knee arthroplasty: A randomized clinical trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015; 473: 34–42.

- Rahbek O, Kold S, Zippor B, Overgaard S, Soballe K. Particle migration and gap healing around trabecular metal implants. Int Orthop 2005; 29: 368–74.

- Ranstam J, Ryd L, Önsten I. Accurate accuracy measurement: review of basic principles. Acta Ortop Scand 2000; 71: 106–8.

- Ryd L. Micromotion in knee arthroplasty: a roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis of tibial component fixation. Act Orthop Scand 1986; Suppl220: 1–80.

- Ryd L, Albrektsson B E, Carlsson L, Dansgard F, Herberts P, Lindstrand A, Regner L, Toksvig-Larsen S. Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis as a predictor of mechanical loosening of knee prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1995; 77(3): 377–83.

- Sagomonyants K B, Hakim-Zargar M, Jhaveri A, Aronow A S, Gronowicz G. Porous tantalum stimulates the proliferation and osteogenesis of osteoblasts from elderly female patients. J Orthop res 2011; 29(4): 609–16.

- Sambaziotis C, Lovy A J, Koller K E, Bloebaum R D, Hirsh D M, Kim S J. Histologic retrieval analysis of a porous tantalum metal implant in an infected primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27(7): 1413e5–1413e9.

- Sundberg M, Lidgren L, W-Dahl A, Robertsson O. Annual report: The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Registry 2015. http://www.myknee.se/pdf/SVK-2015_1.1pdf

- Ström H, Nilsson O, Milbrink J, Mallmin H, Larsson S. Early migration pattern of the uncemented CLS stem in total hip arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Rel Res 2006; 454: 127–32.

- Terré R A. Estimated survival probability of the Spotorno total hip arthroplasty after 15- to 21-year follow-up: one surgeon’s results. Hip Int 2010; 20 (Suppl 7): S70–S78

- Toksvig-Larsen S, Ryd L. Surface flatness after bone cutting: a cadaver study of tibial condyles. Acta Orthop Scand 1991; 62: 15–8.

- Toksvig-Larsen S, Ryd L, Lindstrand A. An internally cooled saw blade for bone cuts. Lower temperatures in 30 knee arthroplasties. Acta Orthop Scand 1990; 61: 321–3.

- Vidalain J P. Twenty-year results of the cementless Corail stem. Int Orthop 2011; 35(2): 189–94.

- W-Dahl A, Robertsson O, Lidgren L. Surgery for knee osteoarthritis in younger patients. A Swedish Register Study. Acta Orthop 2010; 81: 161–4.

- Wilson D A J, Richardson G, Hennigar A W, Dunbar M J. Continued stabilization of trabecular metal tibial monoblock total knee arthroplasty components at 5 years – measured with radiostereometric analysis. Acta Orthop 2012; 8(1): 36–40.

- Wolf O, Mattsson P, Milbrink J, Larsson S, Mallmin H. Periprosthetic bone mineral density and fixation of the uncemented CLS stem related to different weight bearing regimes. A randomized study using DXA and RSA in 38 patients followed for 5 years. Acta Orthop 2010; 81(3): 286–91.

- Zardiackas L D, Parsell D E, Dillon L D, Mitchell D W, Nunnery L A, Poggie R. structure, metallurgy, and mechanical properties of a porous tantalum foam. J Biomed Mater Res 2001: 58(2): 180–7.