Abstract

Background and purpose — The epidemiology and optimal diagnostics of wrist injuries in children are not knotwn. We describe fractures revealed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in a prospective population of children and adolescents with posttraumatic radial-sided wrist tenderness, and compare the diagnostic value of radiographs and computed tomography (CT) with that of MRI.

Patients and methods — From 2004 to 2007, patients less than 18 years of age who presented at our emergency department were included in the study. 90 wrists in 89 patients underwent clinical, radiographic, and low-field MRI investigation. If plain radiographs or MRI revealed a scaphoid fracture, a supplementary CT scan was performed. Sensitivity and specificity of radiographs and CT for diagnosis of scaphoid fractures was calculated using MRI as the reference standard.

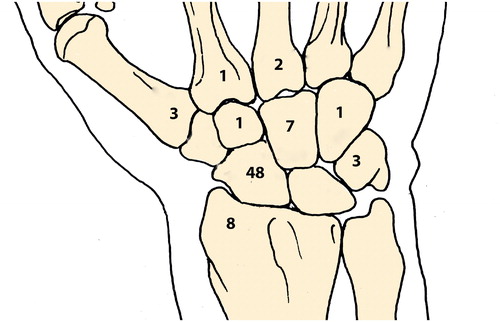

Results — 74 fractures were diagnosed in 61 of 90 wrists using MRI; 48 wrists had a scaphoid fracture, 8 had a distal radius fracture, 7 had a capitate fracture, and 3 had a triquetrum fracture. The most common combination of fractures was scaphoid and capitate. The sensitivity of radiographs for visualization of scaphoid fractures was 54% and the specificity was 100%. The sensitivity for other fractures was <50%. The sensitivity of CT for visualization of scaphoid fractures was 96% and it was between 33% and 100% for other fractures.

Interpretation — MRI showed a high incidence of fractures in children and adolescents with posttraumatic radial wrist tenderness, and it led to the diagnosis of more fractures than plain radiographs and CT. A scaphoid fracture was the most common carpal injury, followed by fracture of the capitate.

The scaphoid is the most commonly fractured carpal bone in children and adolescents, and accounts for 5% of hand and carpal fractures in childhood (Brudvik and Hove Citation2003). Management of suspected scaphoid injuries in children is mainly based on knowledge from similar injuries in adults. However, in children the clinical picture is often more difficult to interpret. Tenderness on palpation in the anatomical snuffbox is not always obvious, as young patients often find it difficult to differentiate the location of pain on the radial side of the wrist and carpus (Evenski et al. Citation2009, Wilson et al. Citation2011). Immature carpal bones are softer and have a stronger bone-ligament interface than in adults, which is why buckle-type fracture and avulsion injuries in children are more common than the typical transverse fracture (Vahvanen and Westerlund Citation1980, Hernandez et al. Citation2002).

The optimal diagnostic modality for detection of wrist injuries in children and adolescents with posttraumatic radial-sided wrist tenderness, including a clinically suspected scaphoid fracture, is not known (Fotiadou et al. Citation2011). Standard radiographic evaluation of the wrist and scaphoid is usually the first-line investigation. However, radiographs alone cannot adequately preclude a scaphoid fracture (Johnson et al. Citation2000, Goddard Citation2005). Second-line investigations include CT and MRI (Johnson et al. Citation2000). In general, CT is easily available but is considered a concern, due to the radiation load (Brody et al. Citation2007). MRI has proven to be useful in the assessment of adult patients with posttraumatic radial-sided wrist tenderness (Jørgsholm et al. Citation2013), and it is advocated as the most reliable diagnostic modality in children with a suspected scaphoid fracture (Johnson et al. Citation2000). However, MRI has limited availability and costs more than radiographs and CT. Previous studies in children with posttraumatic radial wrist tenderness were based on radiographs, while CT and MRI have been used only in cases where the initial radiographs were normal (Gholson et al. Citation2011, Ahmed et al. Citation2014). Thus, our knowledge of the incidence and distribution of fractures in children with posttraumatic radial-sided wrist tenderness is limited and the relative diagnostic performance of radiographs, CT, and MRI has not been investigated.

The main aim of this study was to describe fracture epidemiology revealed by low-field MRI in patients less than 18 years of age with posttraumatic radial-sided wrist tenderness. Secondly, we wanted to assess the diagnostic performance of radiographs and CT in patients with a carpal fracture using low-field MRI as the reference standard.

Patients and methods

Patients

Over a 3-year period (March 1, 2004 to February 28, 2007), all patients who presented at our emergency department with posttraumatic radial wrist tenderness were asked to participate in the study.

The inclusion criteria were age less than 18 years and tenderness on the radial side of the wrist, distal to the radiocarpal joint and proximal to the carpometacarpal articulations, after a trauma. The physical examination included testing for tenderness along the anatomical snuffbox, at the scaphoid tubercle, and by pressing the thumb in its longitudinal direction. The exclusion criterion was a delay of more than 14 days from injury to MRI. 89 patients (90 wrists) met the eligibility criteria.

Imaging

Initial plain radiographs included the wrist in postero-anterior and lateral projections, and 4 additional views of the scaphoid (postero-anterior with ulnar deviation, with the central beam angled 10° cranially, 10° caudally, 20° ulnarly, and 20° radially). Regardless of the result from the radiographs, MRI of the injured wrist was scheduled and was performed within 3 working days of inclusion in the study. If radiographs or MRI revealed a scaphoid fracture, a supplementary CT scan of the wrist was performed immediately.

For MRI, a 0.23-Tesla low-field MRI unit was used (Proview; Marconi Medical Systems, Vantaa, Finland) with a dedicated small joint coil and the following study protocol: coronal short tau inversion recovery (STIR), 3-mm slice thickness; coronal T1 field echo 3-dimensional (FE3D), 2-mm slice thickness; axial T1 fast spin-echo (FSE), 3.5-mm slice thickness; and sagittal T1 field echo 3-dimensional (FE3D), 2-mm slice thickness.

For CT, we used a 16-slice scanner (Somatom Sensation 16; Siemens AG, Forchheim, Germany). The patient was placed prone with the hand to be examined above the head (superman position). A scout view was obtained before the scan. Axial sections of 0.6-mm thick slices were obtained, enabling 1- or 2-mm thick reconstructions in the coronal and sagittal planes defined by the long axis of the scaphoid. The radiation dose for the CT scan was calculated to be approximately 0.02 mSv.

On plain radiographs, a fracture was defined as a break in the continuity of bone. The epiphyses were considered to be open if the first metacarpal had a visible fully open epiphyseal line on the postero-anterior projection. Otherwise, the epiphyses were considered to be closed. On CT, a fracture was defined as the presence of a sharp lucent line within the trabecular bone, a breakage in the continuity of the cortex, a sharp step in the cortex, or a dislocation of bone fragments (Memarsadeghi et al. Citation2006). MRI was considered to be positive for a fracture when cortical and trabecular fractures were present, causing intramedullary hyperintensity on the STIR and also intramedullary hypointensity on T1-weighted images extending to the cortices (Breitenseher et al. Citation1997). Bone bruise was diagnosed when there was only a zone of diffusely increased signal intensity on STIR images (Memarsadeghi et al. Citation2006).

The radiologist on call evaluated the initial radiographs. Subsequently, evaluation of all MR and CT examinations and also re-evaluation of the initial radiographs were done by the same senior musculoskeletal radiologist (JB). Inter-observer agreement was tested by letting one of the participating surgeons (PJ) assess all MR scans in blind fashion.

Statistics

Data analysis was carried out using SPSS version 23. Sensitivity and specificity with 95% confidence interval (CI) for proportions were calculated for radiographs, and sensitivity only for CT, using the exact method by Clopper and Pearson. MRI was used as the reference standard for comparison. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare fracture distribution in wrists with open epiphyses and in those with closed epiphyses. Any p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Inter-observer agreement was analyzed with kappa statistics, including calculations of CI. Kappa values from 0 to 0.2 suggest poor agreement, 0.2 to 0.4 fair, 0.4 to 0.6 moderate, 0.6 to 0.8 good, and 0.8 to1.0 excellent agreement (Landis and Koch Citation1977).

Ethics

The regional ethics committee approved the study design (LU 459-03) and written consent was obtained from the patients and their parents.

Results

89 patients with 90 injured wrists were included (57 males and 32 females, median age 14 (8–17) years). MRI was done within a median of 2 (0–14) days after injury.

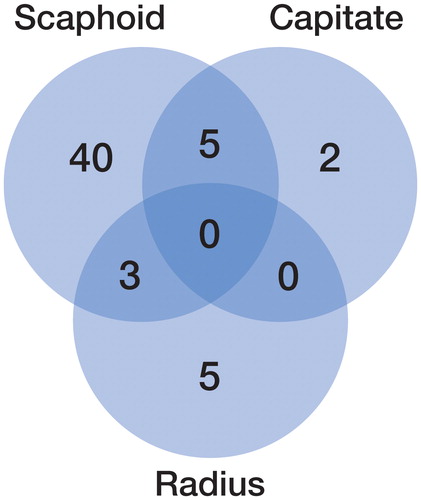

MRI diagnosed 74 fractures in 61 of the 90 wrists investigated: 48 scaphoid fractures, 12 fractures of other carpal bones, 8 distal radius fractures, and 6 metacarpal base fractures (). A scaphoid fracture in combination with another fracture was found in 10 wrists. The most common fracture combination was a scaphoid fracture and a capitate fracture (n = 5) (), followed by combined fracture of the scaphoid and the distal radius (n = 3) and the scaphoid and triquetrum (n = 2). In 1 wrist, a metacarpal fracture was combined with fractures of the capitate, hamate, and trapezoid—the latter carpal fractures being visible on MRI only. Finally, MRI revealed 1 wrist with bone bruise, located in the capitate. A comparison between radiographs and MRI showed that radiographs alone showed 34 of the 74 fractures, which corresponds to an overall sensitivity of 46%. Sensitivity in the diagnosis of scaphoid fractures reached 54%, distal radius fractures 50%, metacarpal fractures 50%, and triquetrum fractures 33%. Sensitivity for other carpal fractures was poor (). Radiographs did not show any false-positive scaphoid fractures compared to MRI, resulting in a specificity of 100% (CI: 92–100).

Figure 2. The distribution of concomitant fractures of the scaphoid, capitate, and distal radius in 90 injured wrists.

Table 1. Number of fractures and sensitivity of radiographs compared to that of MRI in children and adolescents with posttraumatic radial-sided wrist tenderness

CT scan was performed in 45 of the 48 wrists that were MRI-positive for a scaphoid fracture. The 3 missing CT scans were not done for logistic or technical reasons. Thus, CT had been performed in 6 out of 7 capitate fractures, in 3 out of 8 distal radius fractures, and in 2 out of 6 metacarpal fractures. CT allowed visualization of 43 scaphoid fractures (corresponding to 96% sensitivity), of 4 capitate fractures (67% sensitivity), of 3 distal radius fractures (100% sensitivity), and of 1 metacarpal fracture (50% sensitivity) ().

Table 2. Number of fractures and sensitivity of CT compared to that of MRI in children and adolescents with posttraumatic radial-sided wrist tenderness

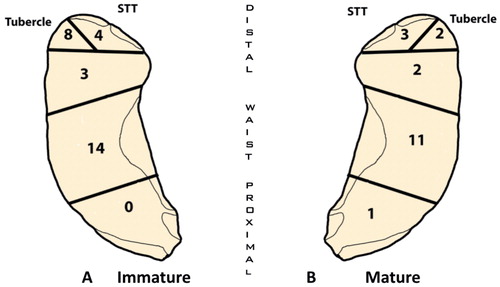

Of the 48 scaphoid fractures detected by MRI, 25 were located in the waist, 22 in the distal pole, and 1 in the proximal pole. 29 fractures (in 21 males and 8 females, mean age 12.2 years) occurred in wrists where the epiphyses were open. 19 fractures (in 14 males and 5 females, mean age 15.1 years) occurred in wrists where the epiphyses were closed (). We did not find any statistically significant difference in fracture pattern between wrists with open epiphyses and those with closed epiphyses (p = 0.3). 7 capitate fractures where diagnosed by MRI. 6 of these (all in males) occurred in wrists with open epiphyses, and the other fracture was found in a female with closed epiphysis.

Figure 3. Anatomical distribution of scaphoid fractures.

A. Immature wrists with open epiphyses (open epiphyses of first metacarpal).

B. Mature wrists with closed epiphyses.

The inter-observer agreement in detecting all fractures on MRI was good (kappa =0.70 (95% CI 0.52–0.87)) and it was excellent in the detection of scaphoid fractures (kappa =0.96 (95% CI: 0.89–1.02)).

Discussion

In this study, a fracture was diagnosed in 61 out of 90 wrists in children and adolescents with posttraumatic radial-sided wrist tenderness. Carpal fractures were common, and the scaphoid predominated with 48 of 60 fractures, followed by the capitate (7 fractures). Compared to low-field MRI, plain radiographs had a low diagnostic performance in detecting carpal fracture in general whereas CT had a high diagnostic performance regarding scaphoid fractures.

If we compare our results in children with those in a previous study on an adult population with posttraumatic radial-sided wrist pain (Jørgsholm et al. Citation2013), the overall frequency of fractures was similar, but the frequency of scaphoid fractures was higher in children than in adults.

The carpal bones have an individual and progressive ossification, starting in the capitate and hamate; through the triquetrum and lunate; then the scaphoid, trapezium, and trapezoid; and finally with ossification occurring in the pisiform. In the scaphoid, ossification progresses from distal to proximal and terminates at about 15 years and 3 months in boys and at about 13 years and 4 months in girls (Stuart et al. Citation1962, Hagg and Taranger Citation1980). The first metacarpal has an ossification that is simultaneous with that of the scaphoid, and it is therefore considered to be a reliable indicator of scaphoid maturity (Stuart et al. Citation1962). The carpal bone that is likely to fracture during an injury, and also the characteristics of the fracture, will depend (among other things) on the degree of ossification. The capitate is the first carpal bone to ossify (Stuart et al. Citation1962), which might explain why we found that 6 out of 7 capitate fractures occurred in the group with open epiphysis and that 7 out of 60 carpal fractures in children and adolescents were located in the capitate—as compared to 14 out of 170 in adults (Jørgsholm et al. Citation2013).

Traditionally, most scaphoid fractures in children, especially in those with an immature skeleton, have been thought to involve the distal pole (Vahvanen and Westerlund Citation1980, Ahmed et al. Citation2014). It should be kept in mind that most previous studies on fracture epidemiology in children have used radiographs for detection and classification of fractures (Vahvanen and Westerlund Citation1980, Nafie Citation1987, Gholson et al. Citation2011, Ahmed et al. Citation2014). We found that distal and waist fractures of the scaphoid were equally common in patients with closed and open physes. Gholson et al. (Citation2011) found a fracture pattern more like that in adults with mainly waist fractures in patients with open epiphyses. However, no definition of open physes was given, patient age was not given for the individual patient groups, and the diagnosis/classification of fractures was mainly based on plain radiographs rather than MRI. A study on patients less than 15 years of age showed that 40 of 94 distal scaphoid fractures were an avulsion fracture from the radial side of the tubercle (Vahvanen and Westerlund Citation1980). In accordance with this, we found tubercle avulsion fractures mainly in wrists with open epiphysis. However, the numbers of distal fractures were too small to be able to make conclusions regarding a higher disposition for tubercle avulsion injuries in patients with open epiphysis.

In adults, plain radiographs allowed detection of 70% of scaphoid fractures and 7% of capitate fractures (Jørgsholm et al. Citation2013) while in our study the diagnostic performance of radiographs was lower, with detection of scaphoid fractures and capitate fractures in 54% and 0% of cases, respectively. This indicates that carpal fractures in children are more difficult to visualize on radiographs. It therefore seems even more important in children with posttraumatic radial-sided wrist pain and normal radiographs to proceed with MRI or CT. Furthermore, it is important to keep in mind that even if radiographs show 1 fracture, there may be more. We found concomitant fractures in 10 out of 48 wrists with a scaphoid fracture. Fracture of the capitate was the most common carpal fracture to occur in combination with a scaphoid fracture. The occurrence of combined carpal fractures in children has been described earlier, and suggests a non-dislocating transcarpal injury force similar to the one described for perilunate injuries in adults (Compson Citation1992, Herzberg Citation2013).

The sensitivity in detecting a capitate fracture when using plain radiographs is poor (0%), and it is modest when using CT (67%). We used a 16-slice CT scanner in this study. Today, 64 or 128 multi-slice CT is standard equipment in many institutions, and it cannot be excluded that a more modern CT scanner would improve the diagnostic performance.

A concern in CT investigations of children has been the radiation load. Even so, the wrist does not contain radiation-sensitive red bone marrow. As CT scan is performed with the wrist above the head (superman position), the radiation load is kept to approximately 0.02 mSv—which is equivalent to 7 days of background radiation (Biswas et al. Citation2009).

We used a low-field (0.23-T) MR scanner, whereas today high-field scanners are standard in most hospitals. They offer a better signal-to-noise ratio and provide better images, although high-field scanners have not been proven to be superior in detecting carpal fractures, as the fracture edema is easily detected on a 0.23-T scanner (Ramnath Citation2006). Due to the noise and cramped conditions, many patients find MRI investigation to be uncomfortable—and more so because they are not allowed to move. The MRI took about 12–15 min, and none of our participating children and adolescents needed sedation to complete the scanning procedure.

When interpreting MRI, it is important to consider that children have a high T2 signal in the carpus during growth, with a maximum around 7–11 years of age, which could theoretically lead to a false-positive result (Shabshin and Schweitzer Citation2009).

The main strength of our study was the large prospective cohort and the fact that all the participants had MRI of the injured wrist. However, it should be kept in mind that our results are not directly comparable to other studies, as we included all patients with posttraumatic radial-sided wrist tenderness and not only those with suspected scaphoid fracture and a normal radiograph (Wilson et al. Citation2011, Ahmed et al. Citation2014). One limitation of the study was that comparison of diagnostic performance between MRI and CT was weakened by not all the patients having CT; also, the number of individual fractures other than those of the scaphoid was too low to allow reliable conclusions to be drawn.

It is not known whether carpal fractures that are diagnosed by MRI but not seen on CT are of any clinical relevance. One could argue that such fractures would heal uneventfully without treatment. The natural history of carpal injuries in children and adolescents that are only detectable by MRI is not known and needs further investigation. In the present study, radiographs were only able to help diagnose 45% of carpal fractures in children and adolescents with posttraumatic radial-sided wrist pain. Thus, second-line investigation such as MRI is recommended to optimize diagnostics, to ensure correct treatment, and to avoid unnecessary immobilization while waiting for a repeated examination.

PJ, NT, SA, and AB designed the study. JB evaluated all the radiographs, CT scans, and MR scans. PJ, NT, and AB investigated participating patients, created a study database, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript. All the authors contributed to discussion of the results, and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

We thank Jonas Björk, PhD, for statistical analysis and Mikael Gunnarsson, PhD, for calculating the radiation load from CT scanning.

- Ahmed I, Ashton F, Tay W K, Porter D. The pediatric fracture of the scaphoid in patients aged 13 years and under: an epidemiological study. J Pediatr Orthop 2014; 34(2): 150–4.

- Biswas D, Bible J E, Bohan M, Simpson A K, Whang P G, Grauer J N. Radiation exposure from musculoskeletal computerized tomographic scans. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2009; 91(8): 1882–9.

- Breitenseher M J, Metz V M, Gilula L A, Gaebler C, Kukla C, Fleischmann D, et al. Radiographically occult scaphoid fractures: value of MR imaging in detection. Radiology 1997; 203(1): 245–50.

- Brody A S, Frush D P, Huda W, Brent R L. Radiation risk to children from computed tomography. Pediatrics 2007; 120(3): 677–82.

- Brudvik C, Hove L M. Childhood fractures in Bergen, Norway: identifying high-risk groups and activities. J Pediatr Orthop 2003; 23(5): 629–34.

- Compson J P. Trans-carpal injuries associated with distal radial fractures in children: a series of three cases. J Hand Surg 1992; 17(3): 311–4.

- Evenski A J, Adamczyk M J, Steiner R P, Morscher M A, Riley P M. Clinically suspected scaphoid fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2009; 29(4): 352–5.

- Fotiadou A, Patel A, Morgan T, Karantanas A H. Wrist injuries in young adults: the diagnostic impact of CT and MRI. Eur J Radiol 2011; 77(2): 235–9.

- Gholson J J, Bae D S, Zurakowski D, Waters P M. Scaphoid fractures in children and adolescents: contemporary injury patterns and factors influencing time to union. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2011; 93(13): 1210–9.

- Goddard N. Carpal fractures in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005; (432): 73–6.

- Hagg U, Taranger J. Skeletal stages of the hand and wrist as indicators of the pubertal growth spurt. Acta Odont Scand 1980; 38(3):187–200.

- Hernandez J A, Swischuk L E, Bathurst G J, Hendrick E P. Scaphoid (navicular) fractures of the wrist in children: attention to the impacted buckle fracture. Emerg Radiol 2002; 9(6): 305–8.

- Herzberg G. Perilunate Injuries, Not Dislocated (PLIND). J Wrist Surg 2013; 2(4): 337–45.

- Johnson K J, Haigh S F, Symonds K E. MRI in the management of scaphoid fractures in skeletally immature patients. Pediatr Radiol 2000; 30(10): 685–8.

- Jørgsholm P, Thomsen N O, Besjakov J, Abrahamsson S O, Björkman A. The benefit of magnetic resonance imaging for patients with posttraumatic radial wrist tenderness. J Hand Surg Am 2013; 38(1): 29–33.

- Landis J R, Koch G G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33(1): 159–74.

- Memarsadeghi M, Breitenseher M J, Schaefer-Prokop C, Weber M, Aldrian S, Gabler C, et al. Occult scaphoid fractures: comparison of multidetector CT and MR imaging–initial experience. Radiology 2006; 240(1): 169–76.

- Nafie S A. Fractures of the carpal bones in children. Injury 1987; 18(2): 117–9.

- Ramnath R R. 3T MR imaging of the musculoskeletal system (Part II): clinical applications. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2006; 14(1): 41–62.

- Shabshin N, Schweitzer M E. Age dependent T2 changes of bone marrow in pediatric wrist MRI. Skeletal Radiol 2009; 38(12): 1163–8.

- Stuart H C, Pyle S I, Cornoni J, Reed R B. Onsets, completions and spans of ossification in the 29 bonegrowth centers of the hand and wrist. Pediatrics 1962; 29: 237–49.

- Vahvanen V, Westerlund M. Fracture of the carpal scaphoid in children. A clinical and roentgenological study of 108 cases. Acta Orthop Scand 1980; 51(6): 909–13.

- Wilson E B, Beattie T F, Wilkinson A G. Epidemiological review and proposed management of ‘scaphoid’ injury in children. Eur J Emerg Med 2011; 18(1): 57–61.