Abstract

Background and purpose — Patients’ expectations of outcomes following arthroscopic meniscus surgery are largely unknown. We investigated patients’ expectations concerning recovery and participation in leisure-time activities after arthroscopic meniscus surgery and the postoperative fulfillment of these.

Patients and methods — The study sample consisted of 491 consecutively recruited patients (mean age 50 (SD 13) years, 55% men) who were assigned for arthroscopy on suspicion of meniscus injury and later verified by arthroscopy. Before surgery, patients completed questionnaires regarding their expectations of recovery time and postoperative participation in leisure activities. 3 months after surgery, the patients completed questionnaires on their actual level of leisure activity and their degree of satisfaction with their current knee function. We analyzed differences between the expected outcome and the actual outcome, and between fulfilled/exceeded expectations and satisfaction with knee function.

Results — 478 patients (97%) completed the follow-up. 91% had expected to be fully recovered within 3 months. We found differences between patients’ preoperative expectations of participation in leisure activities postoperatively and their actual participation in these, with 59% having unfulfilled expectations (p < 0.001). Satisfaction with current knee function was associated with expectations of leisure activities being fulfilled/exceeded.

Interpretation — In general, patients undergoing arthroscopic meniscus surgery were too optimistic regarding their recovery time and postoperative participation in leisure activities. This highlights the need for shared decision making which should include giving the patient information on realistic expectations of recovery time and regarding participation in leisure-time activities after meniscal surgery.

Arthroscopic meniscal surgery is the most frequent orthopedic procedure in the USA, with more than 700,000 procedures being performed annually (Cullen et al. Citation2009) and with increasing use during the last decade (Kim et al. Citation2011). Similar trends of increased use have recently been reported in Denmark and the UK (Thorlund et al. Citation2014, Hamilton and Howie Citation2015).

Despite its frequent use, little is known about patients’ expectations of arthroscopic meniscus surgery regarding recovery time and participation in leisure-time activities after surgery. The mean recovery time expected by orthopedic surgeons for the average patient with an isolated meniscal tear has been reported to be 5 weeks or less (Roos et al. Citation2000).

A recent systematic review found that patients generally overestimate or underestimate the benefits of different treatments in various medical disciplines (Hoffmann and Del Mar Citation2015), and it has been found that patients’ expectations regarding participation in demanding physical activities after total knee joint replacement are usually not fulfilled (Nilsdotter et al. Citation2009). Similar results have been reported for patients who undergo less invasive joint surgery, such as arthroscopic surgery for femoroacetabular impingement (Mannion et al. Citation2013). However, to our knowledge this has not been investigated in patients who undergo arthroscopic meniscus surgery, although it is well known that return to sport is a major expectation in many of these patients (Mancuso et al. Citation2001).

Identification and matching of patients’ expectations with the actual experienced outcome may improve patient satisfaction (Thompson and Sunol Citation1995, Mancuso et al. Citation1997, Noble et al. Citation2006, Bourne et al. Citation2010, Vissers et al. Citation2010, Scott et al. Citation2012, Hamilton et al. Citation2013). To determine what constitutes realistic expectations in arthroscopic meniscus surgery, we need to know more about patients’ expectations and the degree of fulfillment of these.

The main aim of the present study was to determine patients’ expectations of recovery time and of participation in leisure activities before arthroscopic meniscus surgery, and the degree of fulfillment of these after surgery. In addition, we wanted to determine the relationship between fulfillment of patients’ preoperative expectations of meniscal surgery and the degree of postoperative satisfaction, and to compare knee status postoperatively in patients with high or low expectations preoperatively and in patients who were satisfied or dissatisfied postoperatively.

Patients and methods

Patients

Data from the Knee Arthroscopy Cohort Southern Denmark (KACS) (Thorlund et al. Citation2013) were used for the present study. KACS is a prospective cohort whereby patients undergoing meniscal surgery are followed.

Patients assigned to arthroscopy on suspicion of meniscal injury were eligible for participation in the study and they were consecutively recruited at Lillebælt Hospital (located in the towns of Vejle and Kolding) and Odense University Hospital (including Svendborg Hospital), Denmark. The recruitment period was from February 1, 2013 to January 31, 2014.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: age ≥18 years and assigned to arthroscopy on suspicion of having a medial and/or lateral meniscus tear by the examining orthopedic surgeon, based on clinical signs and MRI (if available); also having an e-mail address and being able to read and understand Danish.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: being scheduled for or having had previous surgical reconstruction of the anterior or posterior cruciate ligament in either knee, having had fracture(s) to the lower extremities (i.e. hip, leg, or foot) in either leg within the previous 6 months at the time of recruitment, not being able (mentally) to answer the questionnaire, and not having any meniscal injury found at arthroscopy.

Questionnaires

Data were collected using e-mail-based questionnaires. Preoperative questionnaires were sent out within 2 weeks before surgery, and questionnaires were also sent 3 months postoperatively to patients who had replied to the preoperative questionnaire. To minimize non-response and loss to follow-up, the participants received a reminder e-mail if no response was received after 4 days and a text message if there was still no response after another 4 days. Finally, an attempt was made to reach the patient by telephone if 4 additional days passed without any response.

Preoperatively, patients’ expectations were assessed regarding participation in leisure activities and time to full postoperative recovery after surgery, using questions previously used to assess expectations in patients undergoing knee replacement (Nilsdotter et al. Citation2009). Expectations regarding time to recovery were assessed with the question: “How long do you think it will take before you have recovered from the surgery?” while expectations regarding participation in leisure activities were assessed with the question: “What expectations do you have for participation in leisure activities after the surgery?”, and the responses were graded on a 7-point Likert scale with the options: (1) sports at competitive level, (2) recreational sports, (3) light sports, (4) heavy household work, (5) light household work, (6) minimal housework, and (7) no housework. Changes experienced postoperatively regarding participation in leisure activities were assessed with the questions: “What kinds of leisure activities are you able to participate in now?”, with similar response options. To investigate high/low preoperative expectations about postoperative participation in activities, we categorized responses (1) and (2) as being “high expectations”, whereas the remaining response options were categorized as being “low expectations”.

The extent to which expectations had been exceeded, had been fulfilled, or had been unfulfilled regarding participation in leisure activities was assessed by comparison of preoperative expectations and participation in leisure-time activities at the 3-month follow-up for each patient. This resulted in 3 categories: expectations being fulfilled, not being fulfilled (≥1 beneath the expected), and being exceeded (≥ 1 above the expected).

Satisfaction with current knee function was assessed both preoperatively and postoperatively with the question: “When you think of your knee function, would you consider that your current condition is satisfactory? For knee function, you should take into account your activities of daily living, sport and recreational activities, your pain and other symptoms, and your quality of life”. This had the response options: Yes/No. This question is commonly used to assess patient-acceptable symptom state (PASS) (Tubach et al. Citation2005), and the same wording was previously used in patients who had had reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament (Ingelsrud et al. Citation2015).

Self-reported knee pain and sport and recreational function (Sport/Rec) were assessed both pre- and postoperatively using 2 subscales of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome score (KOOS) (Roos et al. Citation1998b). The score ranges from 0 to 100 (with 0 indicating extreme symptoms and 100 indicating no symptoms). KOOS has been validated and has already been used to assess outcomes in patients undergoing meniscus surgery (Roos et al. Citation1998a, Citationb, Herrlin et al. Citation2007, Citation2013, Katz et al. Citation2013).

The patients were asked about duration of symptoms at baseline and onset of symptoms: “How did the knee pain/problems for which you are now having surgery develop? (Choose the answer that best matches your situation)” and had the response options: “The pain/problems have slowly evolved over time”, “As a result of a specific incident (e.g. kneeling, sliding, and/or twisting of the knee, or the like)”, “As a result of a violent incident (e.g. during sports, a crash, a collision, or the like)”. Information about meniscal tissue quality and cartilage was recorded by the operating surgeon at arthroscopy using a modified version of the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine (ISAKOS) classification of meniscal tears questionnaire (Anderson et al. Citation2011) (including scoring of cartilage using the ICRS grading system) (Brittberg and Winalski Citation2003).

Statistics

Descriptive results are given as mean and standard deviation (SD), median and interquartile range (IQR), or number and percentage as appropriate. Expectations of recovery time and participation in leisure activities together with actual postoperative participation level are presented in graphs with percentages and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Differences between the expected level of participation in leisure activities and the actual level experienced were analyzed with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. To study differences between age groups regarding preoperative expectations, the Mann-Whitney test was used, whereas the chi-squared test was used to study differences between age groups regarding the expected time taken for recovery and fulfillment of expectations for leisure activities. Logistic regression was used to investigate the relationship between fulfillment of preoperative expectations regarding participation in leisure activities and postoperative satisfaction with current knee function. For this analysis, expectations were dichotomized in 2 groups: fulfilled/exceeded and not fulfilled, which was used as the independent variable. Postoperative satisfaction with current knee condition was used as the dependent variable, while age, sex, and BMI were added as potential confounders in the model.

In addition, using multiple linear regression we investigated whether patients who were satisfied with their postoperative knee function had higher postoperative KOOS scores (i.e. Pain and Sport/Rec function) than those who were not satisfied. Also, multiple linear regression was used to investigate whether patients with high preoperative expectations of participation in leisure activities had higher postoperative KOOS scores (i.e. Pain and Sport/Rec function) than patients with lower expectations. Age, sex, BMI, and KOOS baseline score were added as covariates in both models. Finally, we tested whether those with high expectations of participation in leisure activities had higher baseline KOOS scores (i.e. Pain and Sport/Rec function) than patients with low expectations, using an unpaired t-test.

Patients who were lost to follow-up were excluded from all analyses. Stata 14.1 was used for all statistical analyses and p-values of 0.05 or less were considered to be statistically significant.

Ethics

The Regional Scientific Ethics Committee of Southern Denmark reviewed the outline of the KACS study and waived the need for ethical approval, as the study includes only a questionnaire and register data. All the patients gave their written informed consent to participate.

Results

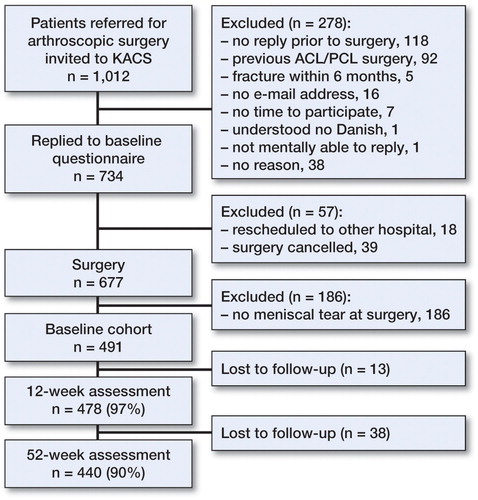

1,012 patients were invited to participate, 335 of whom were excluded for various reasons before baseline assessment and another 186 of whom were excluded after surgery because of not having a meniscal injury, leaving 491 for the 3-month follow-up assessment. Of these, 478 completed the follow-up assessment with a mean follow-up time of 13 (SD 1.6) weeks, giving a proportion of 97% ( and ).

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics. Values are number (percentage) unless otherwise stated

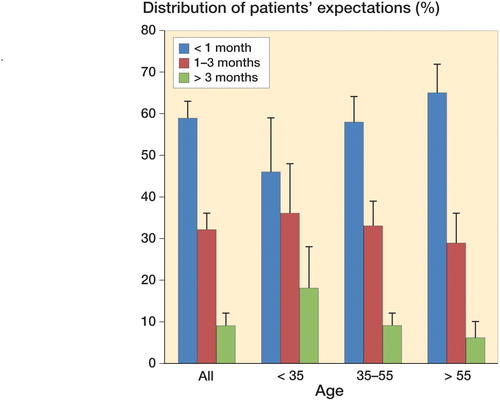

Most of the patients expected that they would be fully recovered within 3 months after surgery and almost 60% expected to have recovered within 1 month (). Patient expectations were significantly different in those who were younger than 35 years and in those who were older than 55 (p = 0.008), with a higher proportion of patients in the older group expecting a shorter recovery time.

Figure 2. Patients’ expectations regarding time to recovery after meniscal surgery, with breakdown into 3 age groups. Bars show proportions and whiskers represent 95% CI.

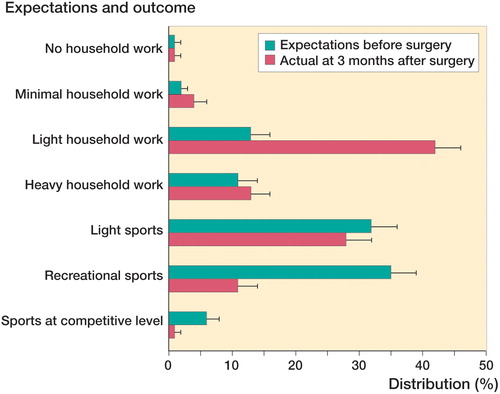

For participation in leisure activities, most patients expected—at least—to be able to participate in light sport (). The expectations of those older than 55 differed significantly from those of the 2 other age groups (p < 0.001), as none in this age group expected to be active at competition level and a larger proportion expected to be active at the level of doing light household work (data not shown). There was no statistically significant difference between the ≤34-year age group and the 35- to 55-year age group.

Figure 3. Distribution of preoperative expectations and actual outcome at follow-up. Bars show proportions and whiskers represent 95% CI.

At 3 months, actual participation in leisure activities differered significantly from preoperative expectations (p < 0.001). Many fewer patients participated in recreational activities than they had expected, and more were active at the level of light household work (). As a consequence, only 41% (95% CI: 36–45) had their preoperative expectations fulfilled or exceeded, whereas the majority did not. The results in this respect were similar between age groups (p = 0.3).

At 3 months, 45% of the patients (95% CI: 41–50) were satisfied with their current knee function, which was significantly more than preoperatively (p < 0.001). The proportion of satisfied patients differed significantly between the 35- to 55-year age group (41% (95% CI: 35–47)) and the >55-year age group (53% (95% CI: 46–61)) (p = 0.01). Fulfilled/exceeded expectations regarding leisure activities were found to predict satisfaction with current knee function, with a crude odds ratio of 3.0 (95% CI: 2.1–4.4) and an adjusted odds ratio of 2.9 (95% CI: 2.0–4.3) (p < 0.001).

KOOS Pain and Sport/Rec scores at 3-month follow-up were statistically significant better for patients who were satisfied with their current knee function than for patients who were not satisfied (). In the crude model, patients with high expectations had higher KOOS scores at 3-month follow-up than those with low expectations, but there was no difference in the adjusted analysis (). Preoperatively, patients with high expectations had higher KOOS pain scores (61 (95% CI: 59–64) vs. 50 (95% CI: 48–52), difference 11 (95% CI: 8–15; p < 0.001)) and higher Sport/Rec scores (31 (95% CI: 28–34) vs. 23 (95% CI: 20–25), difference 8 (95% CI: 4–12; p < 0.001)) than patients with low expectations.

Table 2. Patients’ KOOS scores at 3-month follow-up, according to satisfaction (yes/no) and expectations (high/low). Values are mean postoperative scores (SD)

Discussion

In general, patients expected fast recovery and a high level of participation in leisure activities after meniscal surgery. However, less than half of them were able to participate in leisure activities at their expected level at the 3-month follow-up, althoug >90% had expected to be fully recovered at this time point. Furthermore, less than 50% were satisfied with their current knee function 3 months after surgery.

Three-quarters of the patients expected to be able to participate in at least light sport after their operation, which is in line with previous findings (Mancuso et al. Citation2001). However, whether these patients had different characteristics from the patients in our study is not known. Furthermore, the time to recovery expected by the patients in our study was short and similar to that expected by orthopedic surgeons for full recovery after meniscal surgery (5 weeks), as reported by Roos et al. (Citation2000). It is possible that clinicians may have caused the patients to be over-optimistic. Furthermore, the information given to patients about what to expect from surgery may have varied depending on the surgeon, but we have no data to support this. Our findings, together with previous reports showing considerable patient-reported disability and pain in middle-aged patients up to 4 years after arthroscopy for meniscal tears (Roos et al. Citation2000, Ericsson et al. Citation2006, Thorlund et al. Citation2010), indicate that expectations about recovery time—by both patients and orthopedic surgeons—are too optimistic. However, whether the term recovery reflected pain, disability, or only surgical trauma is not known.

Another factor that may contribute to overly optimistic expectations is stories about quick recovery in professional athletes, as pointed out by Zarins et al. (Citation1985). Indeed, this is a small, although highly visible group of patients who have access to healthcare resources (including rehabilitation) that are not available to most other patients, and they are likely to have a much higher possibility of quick recovery due to a higher level of preoperative functioning.

It is surprising that patients over 55 years of age had higher expectations regarding recovery time than the youngest group (i.e. ≤ 34 years). This indicates that clinicians fail to inform them about what to expect from surgery, despite the increasing focus on the lack of effect of meniscal surgery compared to sham surgery—and in addition to exercise therapy for middle-aged and older patients as repeatedly reported in the literature (Moseley et al. Citation2002, Herrlin et al. Citation2007, Kirkley et al. Citation2008, Herrlin et al. Citation2013, Katz et al. Citation2013, Sihvonen et al. Citation2013, Yim et al. Citation2013) and also recently summarized in a systematic review and meta-analysis (Thorlund et al. Citation2015).

Less than half of the patients were satisfied with their knee function 3 months after arthroscopy. Whether or not this improves with time is currently unknown. The low satisfaction rate that we found may partly be explained by the fact that less than half of them had their preoperative expectations about participation in leisure activities fulfilled or exceeded, as fulfilled/exceeded expectations were associated with a 3-fold increased likelihood of satisfaction with current knee function. Similar associations between level of participation in physical activity/leisure activities and satisfaction have been reported in several studies on patients undergoing total joint replacement surgery (Mancuso et al. Citation1997, Noble et al. Citation2006, Bourne et al. Citation2010, Vissers et al. Citation2010, Scott et al. Citation2012, Hamilton et al. Citation2013). However, satisfaction rate may partly be explained by the postoperative knee status (i.e. level of pain and function), as shown by earlier studies concerning surgery to the lower extremities (Mannion et al. Citation2009, Suda et al. Citation2010, Vissers et al. Citation2010, Hamilton et al. Citation2013). We found a difference in Pain and Sport/Rec function scores between satisfied and dissatisfied patients 3 months after surgery. Furthermore, some studies on expectations after lower extremity surgery have found an association between high preoperative expectations and better outcome (Mahomed et al. Citation2002, Gandhi et al. Citation2009, Judge et al. Citation2011), possibly reflecting the influence of dispositional optimism on outcome (Thompson and Sunol Citation1995, Barron et al. Citation2007). We found that patients with better knee status at baseline had higher expectations, but there was no association between high expectations and better outcome at 3 months after adjusting for possible confounders. We have not been able to find previous reports on this in patients who undergo meniscal surgery.

Shared decision making is a consultation process where the clinician and patient jointly discuss treatment options and their benefits and harms, considering the patient’s values, preferences, and circumstances (Hoffmann et al. Citation2014). Our findings show that patients’ expectations about the effects of treatment are generally too optimistic, which is similar to findings in other fields ofmedicine (Nilsdotter et al. Citation2009, Mannion et al. Citation2013, Hoffmann and Del Mar Citation2015). Whether this is caused by patients’ beliefs in surgery or whether it is influenced by clinicians is unknown. Nevertheless, the results emphasize the need for balancing of patients’ expectations of outcome after meniscal surgery during the shared decision making process.

Our cohort included patients assigned for arthroscopy on the suspicion of having meniscal injury, which was later verified by arthroscopy from 2 different hospitals at 4 different sites. Along with the low number of exclusion criteria, this increases the external validity of the study. It is further supported by the fact that the demographics of the patients included—with regard to gender and age—are very similar to those in previous reports on all patients undergoing meniscal surgery in Denmark (Thorlund et al. Citation2014). However, it is not known whether the results differ between patients who have and have not had previous experience of failed non-surgical treatments before surgery, as we do not have information on participation or the type of non-surgical treatments that they may have been offered prior to surgery. It is likely, though, that expectations of surgery can be affected by previous treatment experiences, since one’s expectations partly come from one’s previous experiences (Thompson and Sunol Citation1995).

A limitation of this study was the use of the question regarding expectations about time to recovery, which had not been validated, so we do not know whether the patients interpreted it as meaning full recovery after the injury or just in the short term after surgery.

In summary, patients assigned to arthroscopic meniscal surgery were generally too optimistic regarding recovery time and postoperative participation in leisure activities. This highlights the need for shared decision making, including giving information about realistic expectations regarding recovery time and participation in leisure-time activities after meniscal surgery.

KP, EMR, and JBT conceived and designed the study. NN, UJ, and JS participated in setting up of the study, patient recruitment, and data collection. KP, EMR, and JBT conducted the analysis and/or interpretation. KP and JBT drafted the first version of the manuscript. All the authors helped to revise the manuscript and gave their final approval of the submitted version.

We thank all the participating patients, the orthopedic surgeons, and the nurses, and also the secretaries of the Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, Odense University Hospital (Odense and Svendborg) and the Department of Orthopedics, Lillebaelt Hospital (Kolding and Vejle) for their assistance with patient recruitment and data collection. The study was supported by an individual postdoctoral grant to JBT from the Danish Council for Independent Research (Medical Sciences) and funds from the Southern Denmark Region.

No competing interests declared.

- Anderson A F, Irrgang J J, Dunn W, Beaufils P, Cohen M, Cole B J, et al. Interobserver reliability of the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine (ISAKOS) classification of meniscal tears. Am J Sports Med 2011; 39 (5): 926–32.

- Barron C J, Moffett J A, Potter M. Patient expectations of physiotherapy: definitions, concepts, and theories. Physiother Theory Pract 2007; 23 (1): 37–46.

- Bourne R B, Chesworth B M, Davis A M, Mahomed N N, Charron K D. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468 (1): 57–63.

- Brittberg M, Winalski C S. Evaluation of cartilage injuries and repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85-ASuppl2: 58–69.

- Cullen K A, Hall M J, Golosinskiy A. Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. Natl Health Stat Report 2009; (11): 1–25.

- Ericsson Y B, Roos E M, Dahlberg L. Muscle strength, functional performance, and self-reported outcomes four years after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in middle-aged patients. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 55 (6): 946–52.

- Gandhi R, Davey J R, Mahomed N. Patient expectations predict greater pain relief with joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2009; 24 (5): 716–21.

- Hamilton D F, Howie C R. Knee arthroscopy: influence of systems for delivering healthcare on procedure rates. BMJ 2015; 351: h4720.

- Hamilton D F, Lane J V, Gaston P, Patton J T, Macdonald D, Simpson A H, et al. What determines patient satisfaction with surgery? A prospective cohort study of 4709 patients following total joint replacement. BMJ Open 2013; 3 (4).

- Herrlin S, Hallander M, Wange P, Weidenhielm L, Werner S. Arthroscopic or conservative treatment of degenerative medial meniscal tears: a prospective randomised trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2007; 15 (4): 393–401.

- Herrlin S, Wange P O, Lapidus G, Hallander M, Werner S, Weidenhielm L. Is arthroscopic surgery beneficial in treating non-traumatic, degenerative medial meniscal tears? A five year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013; 21 (2): 358–64.

- Hoffmann T C, Del Mar C. Patients’ expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175 (2): 274–86.

- Hoffmann T C, Legare F, Simmons M B, McNamara K, McCaffery K, Trevena L J, et al. Shared decision making: what do clinicians need to know and why should they bother? Med J Aust 2014; 201 (1): 35–9.

- Ingelsrud L H, Granan L P, Terwee C B, Engebretsen L, Roos E M. Proportion of patients reporting acceptable symptoms or treatment failure and their associated KOOS values at 6 to 24 months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a study from the Norwegian Knee Ligament Registry. Am J Sports Med 2015; 43 (8): 1902–7.

- Judge A, Cooper C, Arden N K, Williams S, Hobbs N, Dixon D, et al. Pre-operative expectation predicts 12-month post-operative outcome among patients undergoing primary total hip replacement in European orthopaedic centres. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011; 19 (6): 659–67.

- Katz J N, Brophy R H, Chaisson C E, de Chaves L, Cole B J, Dahm D L, et al. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med 2013; 368 (18): 1675–84.

- Kim S, Bosque J, Meehan J P, Jamali A, Marder R. Increase in outpatient knee arthroscopy in the United States: a comparison of National Surveys of Ambulatory Surgery, 1996 and 2006. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93 (11): 994–1000.

- Kirkley A, Birmingham T B, Litchfield R B, Giffin J R, Willits K R, Wong C J, et al. A randomized trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med 2008; 359 (11): 1097–107.

- Mahomed N N, Liang M H, Cook E F, Daltroy L H, Fortin P R, Fossel A H, et al. The importance of patient expectations in predicting functional outcomes after total joint arthroplasty. J Rheumatol 2002; 29 (6): 1273–9.

- Mancuso C A, Salvati E A, Johanson N A, Peterson M G, Charlson M E. Patients’ expectations and satisfaction with total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 1997; 12 (4): 387–96.

- Mancuso C A, Sculco T P, Wickiewicz T L, Jones E C, Robbins L, Warren R F, et al. Patients’ expectations of knee surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83-A (7): 1005–12.

- Mannion A F, Kampfen S, Munzinger U, Kramers-de Quervain I. The role of patient expectations in predicting outcome after total knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Res Ther 2009; 11 (5): R139.

- Mannion A F, Impellizzeri F M, Naal F D, Leunig M. Fulfilment of patient-rated expectations predicts the outcome of surgery for femoroacetabular impingement. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013; 21 (1): 44–50.

- Moseley J B, O’Malley K, Petersen N J, Menke T J, Brody B A, Kuykendall D H, et al. A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med 2002; 347 (2): 81–8.

- Nilsdotter A K, Toksvig-Larsen S, Roos E M. Knee arthroplasty: are patients’ expectations fulfilled? A prospective study of pain and function in 102 patients with 5-year follow-up. Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (1): 55–61.

- Noble P C, Conditt M A, Cook K F, Mathis K B. The John Insall Award: Patient expectations affect satisfaction with total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 452: 35–43.

- Roos E M, Roos H P, Ekdahl C, Lohmander L S. Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)–validation of a Swedish version. Scand J Med Sci Sports 1998a; 8 (6): 439–48.

- Roos E M, Roos H P, Lohmander L S, Ekdahl C, Beynnon B D. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)–development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1998b; 28 (2): 88–96.

- Roos E M, Roos H P, Ryd L, Lohmander L S. Substantial disability 3 months after arthroscopic partial meniscectomy: A prospective study of patient-relevant outcomes. Arthroscopy 2000; 16 (6): 619–26.

- Scott C E, Bugler K E, Clement N D, MacDonald D, Howie C R, Biant L C. Patient expectations of arthroplasty of the hip and knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012; 94 (7): 974–81.

- Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itala A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med 2013; 369 (26): 2515–24.

- Suda A J, Seeger J B, Bitsch R G, Krueger M, Clarius M. Are patients’ expectations of hip and knee arthroplasty fulfilled? A prospective study of 130 patients. Orthopedics 2010; 33 (2): 76–80.

- Thompson A G, Sunol R. Expectations as determinants of patient satisfaction: concepts, theory and evidence. Int J Qual Health Care 1995; 7 (2): 127–41.

- Thorlund J B, Aagaard P, Roos E M. Thigh muscle strength, functional capacity, and self-reported function in patients at high risk of knee osteoarthritis compared with controls. Arthritis Care Res 2010; 62 (9): 1244–51.

- Thorlund J B, Christensen R, Nissen N, Jorgensen U, Schjerning J, Porneki J C, et al. Knee Arthroscopy Cohort Southern Denmark (KACS): protocol for a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2013; 3 (10): e003399.

- Thorlund J B, Hare K B, Lohmander L S. Large increase in arthroscopic meniscus surgery in the middle-aged and older population in Denmark from 2000 to 2011. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (3): 287–92.

- Thorlund J B, Juhl C B, Roos E M, Lohmander L S. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee: systematic review and meta-analysis of benefits and harms. BMJ 2015; 350: h2747.

- Tubach F, Ravaud P, Baron G, Falissard B, Logeart I, Bellamy N, et al. Evaluation of clinically relevant states in patient reported outcomes in knee and hip osteoarthritis: the patient acceptable symptom state. Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64 (1): 34–7.

- Vissers M M, de Groot I B, Reijman M, Bussmann J B, Stam H J, Verhaar J A. Functional capacity and actual daily activity do not contribute to patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010; 11: 121.

- Yim J H, Seon J K, Song E K, Choi J I, Kim M C, Lee K B, et al. A comparative study of meniscectomy and nonoperative treatment for degenerative horizontal tears of the medial meniscus. Am J Sports Med 2013; 41 (7): 1565–70.

- Zarins B, Boyle J, Harris B A. Knee rehabilitation following arthroscopic meniscectomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1985; (198): 36–42.