Abstract

Background and purpose — Backside wear of the polyethylene insert in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) can produce clinically significant levels of polyethylene debris, which can lead to loosening of the tibial component. Loosening due to polyethylene debris could theoretically be reduced in tibial components of monoblock polyethylene design, as there is no backside wear. We investigated the effect of 2 different tibial component designs, monoblock and modular polyethylene, on migration of the tibial component in uncemented TKA.

Patients and methods — In this randomized study, 53 patients (mean age 61 years), 32 in the monoblock group and 33 in the modular group, were followed for 2 years. Radiostereometric analysis (RSA) was done postoperatively after weight bearing and after 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. The primary endpoint of the study was comparison of the tibial component migration (expressed as maximum total point motion (MTPM)) of the 2 different implant designs.

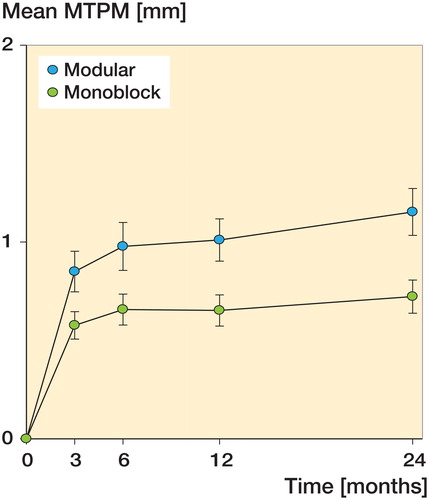

Results — We did not find any statistically significant difference in MTPM between the groups at 3 months (p = 0.2) or at 6 months (p = 0.1), but at 12 and 24 months of follow-up there was a significant difference in MTPM of 0.36 mm (p = 0.02) and 0.42 mm (p = 0.02) between groups, with the highest amount of migration (1.0 mm) in the modular group. The difference in continuous migration (MTPM from 12 and 24 months) between the groups was 0.096 mm (p = 0.5), and when comparing MTPM from 3–24 months, the difference between the groups was 0.23 mm (p = 0.07).

Interpretation — In both study groups, we found the early migration pattern expected, with a relatively high initial amount of migration from operation to 3 months of follow-up, followed by stabilization of the implant with little migration thereafter. However, the modular implants had a statistically significantly higher degree of migration compared to the monoblock. We believe that the greater stiffness of the modular implants was the main reason for the difference in migration, but an initial creep in the polyethylene metal-back locking mechanism of the modular group could also be a possible explanation for the observed difference in migration between the 2 study groups.

Aseptic loosening of tibial components in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is still the most common reason for revision surgery (Lombardi et al. Citation2014, Thiele et al. Citation2015). Particle reaction induced by polyethylene debris can lead to periprosthetic osteolysis through an inflammatory response and result in loosening of the implant (Peters et al. Citation1992, Jacobs et al. Citation2001, Noordin and Masri Citation2012, Gallo et al. Citation2013a, Citation2013b). Backside wear of the polyethylene insert can produce clinically significant levels of polyethylene debris (Peters et al. Citation1992, Holleyman et al. Citation2015). Loosening due to polyethylene debris could theoretically be reduced in tibial components of monoblock polyethylene design, as there is no backside wear. Revisions where only the polyethylene is changed make up only a small proportion of the total number of revisions, and high rates of subsequent revisions have been reported (Engh et al. Citation2000, Babis et al. Citation2002, Thiele et al. Citation2015).

Radiostereometric analysis (RSA) is the best method for predicting aseptic loosening of artificial joints. The precision of the RSA method allows identification of implants with a high degree of migration at an early stage and implants with continuous migration, both of which are predictors of later revision because of aseptic loosening (Karrholm Citation1989, Ryd et al. Citation1995, Pijls et al. Citation2012).

The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register indicates that there is worse survivorship for the early designs of uncemented tibial components than for cemented tibial components (Knutson and Robertsson Citation2010), while other registries have found that uncemented tibial components to have similar revision rates and similar clinical outcomes to those of cemented components (Graves et al. Citation2004). There have been several RSA studies showing continuous migration of cemented tibial components (Karrholm Citation1989, Nilsson et al. Citation1991, Citation1999). This is probably due to bone resorption in the bone-cement interface, so uncemented implants should not have this problem (Linder Citation1994).

The aim of this prospective randomized study was to investigate the migration of uncemented tibial components with a tantalum trabecular metal surface (Nexgen; Zimmer, Warsaw, IN) in a population of young patients (< 70 years of age), comparing monoblock design and modular polyethylene design. The primary endpoint was comparison of migration expressed as maximum total point motion (MTPM) of the tibial component designs at each follow-up over a 24-month follow-up period. Calculation of sample size was based on MTPM as primary outcome. Secondary explanatory endpoints were segment motions (translations and rotations) in order to understand underlying directional migrations. To our knowledge, no other RSA studies comparing this difference in polyethylene design for uncemented TKAs have been published. Previously, however, the uncemented monoblock tibial components with trabecular metal surfaces have shown both good initial fixation and very low long-term migration in RSA studies (Henricson et al. Citation2008, Dunbar et al. Citation2009, Wilson et al. Citation2012).

Patients and methods

Patients and implants

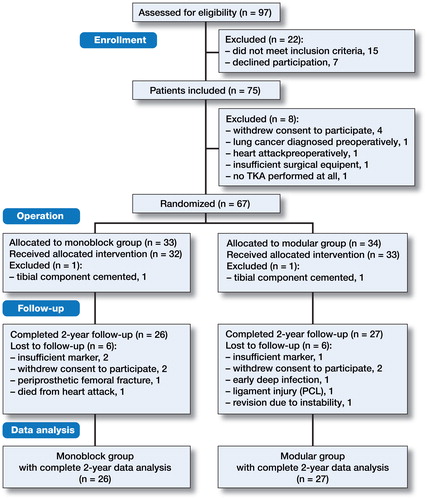

75 patients scheduled for TKA surgery with a cruciate retaining TKA because of osteoarthritis were included in a prospective randomized clinical trial with 2 years of follow-up. All the patients included were under 70 years of age at the time of the operation, and suffered no bone-related diseases other than osteoarthritis. The patients were randomized to receive either the monoblock or the modular polyethylene design version of the Cruciate Retaining Trabecular Metal Technology Nexgen tibial component (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN) (). The femoral components used in all patients were the cruciate retaining, uncemented titanium Nexgen Flex (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN), and all patients had a cemented Nexgen all-poly patellar component (Zimmer). Inclusion was done during the period August 6, 2012 through April 25, 2013. All operations were performed by experienced knee surgeons at the Department of Orthopedics, Herlev Gentofte Hospital, Denmark. Randomization (block randomization with 12 in each block) was performed in the operating theater by opening a sealed envelope just before skin incision.

Of the 75 patients included in the study, 8 were excluded before randomization because: the patient withdrew his/her consent to participate in the study (n = 4), or surgery was not performed (n = 4). In 2 cases, the surgeon decided to cement the tibial component after randomization (n = 2) (). Thus, 65 patients (mean age 61 years; 37 women and 28 men) received the allocated intervention, with 32 in the monoblock group and 33 in the modular group (). 12 additional patients were lost to follow-up at the final 2-year follow-up data analysis, for different reasons ().

Figure 2. Flow chart. Monoblock versus modular: inclusion, randomization, follow-up, and data analysis.

Table 1. Baseline demographics. Patients to receive allocated intervention (n = 65). Values are mean (range) unless otherwise stated

Conventional standing radiographs were taken pre- and postoperatively, to determine knee alignment and the degree of osteoarthritis. All patients were evaluated clinically regarding knee function using the Knee Society score (KSS) (Insall et al. Citation1989), preoperatively and at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. Furthermore, self-assessment of quality of life was evaluated using the EQ-VAS visual analog scale (Devlin et al. Citation2010), preoperatively and at each follow-up.

Radiostereometric analysis

The RSA analyses were done using marker-based software (UmRSA v6.0; RSA Biomedical, Umeå, Sweden). Tantalum markers were inserted in the tibial host bone (0.8 mm) and in the polyethylene of the prosthesis (1 mm) during surgery, a method that has been repeatedly validated (Nilsson et al. Citation1991, Ryd et al. Citation1995, Nilsson et al. Citation1999, Dunbar et al. Citation2009, Wilson et al. Citation2012). Markers were placed to create the largest possible non-linear segments. To ensure comparable MTPM and translational data in the 2 groups, the tantalum beads were placed in a corresponding pattern in both types of implants. 6 markers were placed systematically by the same person at all operations: 2 were placed posteriorly, 2 were placed at the most medial/lateral part of the polyethylene curve, and 2 markers were placed anteriorly.

Postoperative RSA was performed after a mean delay of 6 (range: 2–10) days in both the modular and monoblock groups, and then after 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. Patients were positioned in a standardized supine position, placing the knee to be investigated in a Plexiglass biplane calibration cage (Calibration cage 21; Tilly Medical Products, Lund, Sweden). The same physician positioned the patients at each examination. Ceiling-mounted moveable X-ray tubes were positioned perpendicular to each other in the anterior-posterior and medial-lateral planes at a distance of 100 cm from the X-ray films, which were placed in portable cassettes. The radio intensity was set to 50 kV and 25 milliampere seconds (mAs) in all examinations. All radiographs (digital 9 pixels per mm) were approved by the same physician to ensure that the quality would suffice. The radiographic images were imported into UmRSA software using DICOM link version 3.0 software (RSA Biomedical, Umeå, Sweden), allowing a resolution of 254 dots per inch.

The distribution of the markers in the rigid bodies is estimated by the software and is expressed as the condition number (CN), and the stability of the markers is expressed as the mean error (ME). A high CN indicates a narrow and linear distribution of markers whereas a low CN indicates good spatial and non-linear marker distribution. If a marker loosens between examinations, the 3D structure of the rigid body deforms, resulting in loss of precision in migration measurements and an increase in ME. UmRSA software therefore allows loose markers to be removed from a rigid body if the ME becomes too high, but this will increase the CN—as the spatial distribution of the markers is usually reduced when a marker is removed.

In order to ensure the reliability of the migration results, the CN cutoff in this study was set to 130 and the ME cutoff was set to 0.300 mm, in accordance with the general guidelines for RSA (Valstar et al. Citation2005). The migration data in this study are presented as MTPM and the segment motion is expressed as rotational and translational motion along and around the X-, Y-, and Z-axes. Translations were measured at a centroid polygon from the 6 markers placed systematically in the insert, and the number of markers was checked at each examination in order ensure that no markers were missing. The results of rotations and translations are presented as signed values.

Statistics and study hypothesis

This was a confirmative trial, and the primary endpoints of the study were comparison of the migration (expressed as MTPM) of the 2 tibial component designs at each follow-up over the 24-month follow-up period. The calculation of sample size given below is based on MTPM (after 2 years) as primary outcome parameter. The segment motion data (translations and rotations) were considered to be secondary explanatory endpoints, which were included in order to understand underlying directional migrations that resulted in the MTPM. We hypothesized that given the very low migration rate of the monoblock component, as seen in previous RSA studies (Henricson et al. Citation2008, Dunbar et al. Citation2009, Wilson et al. Citation2012), we would find less migration in the monoblock group than in the modular group.

The migration data (MTPM and segment motions) in both groups were not normally distributed. We used the Wilcoxon signed rank test for changes in migration over time within the groups, and the Mann-Whitney U-test for differences in migration between the groups. Clinical outcome data were also compared between the groups using the Mann-Whitney U-test.

We performed 49 double measurements to calculate the precision error for RSA measurements of migration in the study. The patients were asked to step off the bearing and to wait 10 minutes before the second set of radiographs were obtained (Valstar et al. Citation2005). We calculated precision error as being 2 standard deviations (2 SD) from a series of theoretical migrations (translations and rotations along all 3 axes, and MTPM) obtained from the 49 pairs of double RSA radiographs.

Statistical analyses were done using SPSS Statistics version 21, and data are presented as mean values together with total range, standard error (SE; for graphical presentations only), or 95% confidence interval (CI). Any p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Sample size

To calculate sample size, we used the average SD of MTPM after 2 years from a study by Toksvig-Larsen et al. (Citation2000) that evaluated 4 different uncemented tibial components. Sample size was calculated to be 24 with an average SD of 0.7 mm, type-1 error of 5%, type-2 error of 15%, and a minimal relevant difference in MTPM of 0.6 mm. 2 groups of 30 subjects were planned to allow for dropouts during the follow-up period.

Ethics and registration

The study was approved by the Scientific Ethical Committee of Copenhagen (H-1-2012-033), and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants (after giving them written and oral information), prior to inclusion in the study. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (ID 01766, GEH-2012-027) and it was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT01637051) before starting.

Results

Clinical results

We performed a 2-year follow-up of 53 patients, with 26 in the monoblock group and 27 in the modular group (). The 2-year clinical outcome of the total population was reflected by an increase in KSS from 29 (10–49) preoperatively to 90 (60–95) at the 24-month follow-up (p < 0.001), and by an increase in KSS function from 52 (30–80) to 92 (50–100) (p < 0.001). No statistically significant differences between the 2 study groups, monoblock and modular, in clinical outcome (expressed as changes in KSS or KSS function) were found at any time during the follow-up (). Self-assessed life quality improved from an average EQ-VAS score of 63 preoperatively to a 2-year average score of 89 (p < 0.001), but there was no statistically significant difference between the groups ().

Table 2. Clinical outcome. Values are mean (range) unless otherwise stated

RSA results

From 49 double measurements we calculated rotational and translational precision error (PE), expressed as 2 SD. For rotational segment motion, we found PE values of 0.16°, 0.24°, and 0.14° for X-, Y-, and Z-rotations, respectively. Translational segment motion PE values were 0.10 mm, 0.14 mm, and 0.16 mm for X-, Y-, and Z-translations, respectively. Precision error for MTPM was 0.16 mm. Mean error was 0.15 (SD 0.06) for the tibia and 0.07 (SD 0.04) for the implant. CN values were 56 (SD 26) and 30 (SD 17), respectively.

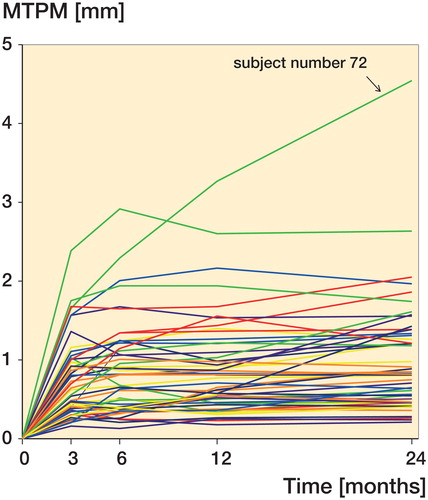

The MTPM results showed the highest average migration initially within the first 3 months in both the modular group and the monoblock group reaching 0.85 mm and 0.58 mm, respectively ( and ). Thereafter, the MTPM migration curves flattened to reach 1.01 mm and 0.65 mm after 12 months, indicating stabilization of the implants. However, there was more migration in the modular group. The difference became statistically significant at 12 months (p = 0.021) and at 24 months (p = 0.017), where the average MTPM was 1.15 mm in the modular group and 0.72 mm in the monoblock group ( and ). The difference in continuous migration (MTPM from 12 and 24 months) between the groups was 0.096 mm (95% CI: −0.03 to 0.16) (p = 0.5), and when comparing MTPM from 3–24 months, the difference between the groups was 0.23 mm (CI: −0.09 to 0.35) (p = 0.07).

Table 3. RSA migration data. Values are mean (95% CI) and duration of follow-up.

There were 3 patients with a high degree of migration, defined as MTPM over 2 mm after 12 months. One of these (subject no. 72), with an extremely high migration of 4.5 mm MTPM at 24 months, belonged to the monoblock group, whereas the other 2 belonged to the modular group (). From 12 to 24 months, 11 subjects showed continuous migration of more than 0.2 mm. Only 1 of the initial 3 patients with high migration was among these subjects (subject no. 72), while the MTPM of the other 2 was below 0.2 mm from 12 to 24 months.

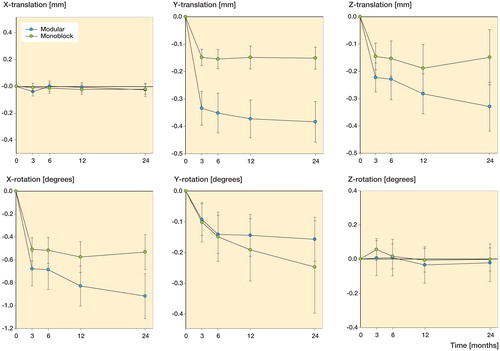

We found the greatest amount of translational migration along the superior-inferior axis (Y-translation). The modular group had an average amount of translation of −0.38 mm after 24 months, which was more than the average of −0.18 mm in the monoblock group (p = 0.03). The negative values indicate a subsidence of the implant in the tibial bone ( and ). Both implants also migrated in a posterior direction along the Z-axis (Z-translation). Again, the largest amount of migration was found in the modular group, with migration on average 0.33 mm posteriorly, but the difference between the groups was not statistically significant (p = 0.07) ( and ). There was almost no translational migration of the implants along the lateral-medial axis (X-translation) ().

We found the greatest amount of rotational migration around the X-axis (anterior-posterior rotation). The modular implants rotated on average −0.92° around the X-axis during the first 24 months, the negative value indicating a 0.92° posterior tilt (). Posterior tilt was also the most pronounced rotational migration in the monoblock group, which rotated −0.53° on average around the X-axis ( and ). There was less rotational migration around the Y-axis (external-internal rotation) after 24 months. The monoblock group had an average amount of rotation of −0.25° and the modular group rotated on average −0.16° around the Y-axis, the negative value indicating an internal rotation in both groups ( and ). There was almost no rotational migration around the Z-axis (varus-valgus tilt) ( and ). None of the differences in rotational migration between the groups were statistically significant.

Discussion

We found a statistically significant difference between the groups after 24 months regarding MTPM and subsidence, with the monoblock tibial component being the most stable implant. In both groups, we found that subsidence and posterior tilt were the most pronounced migratory movements of the implants. When comparing the continuous migration from 3–24 months and 12–24 months, the difference between the groups was not statistically significant—indicating that most of the difference between the 2 types of implants occurred within the first 3 months postoperatively. Thus, the migration beyond the first year, which has traditionally been considered to be the most clinically relevant for prediction of later aseptic loosening (Ryd et al. Citation1995), was not found to be statistically different in the 2 study groups.

There is no obvious explanation for the higher degree of migration in the modular group. The groups were comparable regarding preoperative age, sex, and BMI. The difference between the groups was not due to extreme outliers, as the study only had 1 extreme outlier (subject no. 72; ), which belonged to the monoblock group. Exclusion of subject no. 72 from the data set only enhanced the difference between the groups. Subject no. 72 suffered from long-term and ongoing alcohol abuse, which was unknown to the researchers at the time of inclusion.

We were not surprised to find that the monoblock component had a stable migration pattern with extremely low migration—almost like cemented implants, because this has been shown in previous RSA studies (Dunbar et al. Citation2009, Stilling et al. Citation2011). Furthermore, recently published long-term follow-ups performed in these studies have shown that the stable migratory pattern of the monoblock tibial component continues beyond 2 years (Wilson et al. Citation2012, Henricson et al. Citation2013).

Since the bone ingrowth surfaces of both types of implants in the present study are similar, both with tantalum trabecular metal, we speculate that the difference between the groups might lie in the mechanical properties of the implants. The modular component has a titanium plate molded on the top of the trabecular metal constituting the locking mechanism, which allows the modularity of the polyethylene. As a consequence, the modular component is stiffer than the monoblock component. The trabecular metal backbone of the monoblock component has a low modulus of elasticity approximating the mechanical properties of the cancellous tibial host bone. The clinical importance of the low stiffness is better load sharing properties for the monoblock component than for the modular component. Also, the thickness of the polyethylene could affect the stiffness of the components. The polyethylene of Nexgen tibial components ranges from 10 mm to 17 mm, and the average polyethylene thickness of the components inserted in the monoblock and modular groups was 11.9 mm and 12.1 mm, respectively, with a very similar distribution, so this difference does not appear to affect the stiffness of the components. Both implants have 2 large hexagonal pegs, which are press-fitted into round holes in the tibia in order to enhance the initial fixation of the implant. The modular component has an additional short, rounded boss to facilitate screw fixation of the 17-mm polyethylene (). We find it unlikely that this difference in design would explain the difference in migration between the groups. If the additional peg in the modular group affected the migration, it would theoretically improve the Y-rotation stability, but we found no statistically significant difference in Y-rotation between the groups.

The monoblock component’s reduced backside wear gives another possible explanation for the difference between the groups, as a reduction in polyethylene debris reduces the risk of aseptic loosening (Peters et al. Citation1992, Jacobs et al. Citation2001, Gallo et al. Citation2013b). However, we would only expect to find the effect of osteolysis and loosening due to polyethylene debris at long-term follow-ups, when polyethylene wear is more pronounced—as shown in previous studies (Peters et al. Citation1992, Feng et al. Citation1994, Wasielewski et al. Citation1994, O’Rourke et al. Citation2002, Dalling et al. Citation2015). Apart from backside wear, the amount of polyethylene debris also depends on factors such as patient weight, physical activity, and pre- and postoperative knee alignment (Gallo et al. Citation2013b), but our groups were also comparable regarding these parameters ( and ).

The marker-based RSA technique requires tantalum beads to be inserted into the polyethylene of the tibial components in order to create the implant segment. The method is well-established and has been used in several previous RSA studies, including studies of modular tibial implants (Ryd Citation1986, Albrektsson et al. Citation1990, Toksvig-Larsen et al. Citation1998, Adalberth et al. Citation2000, Toksvig-Larsen et al. Citation2000, Catani et al. Citation2004, Hyldahl et al. Citation2005, Hilding and Aspenberg Citation2006, Hansson et al. Citation2008, Henricson et al. Citation2008). However, theoretically the difference in MTPM between the groups could be due to movements between the metal and the polyethylene in the locking mechanism of the modular component. There is no way to discriminate such movement from implant migration, when the markers are placed in the polyethylene. When comparing the continuous migration from 3–24 months and 12–24 months, the difference between the groups was not statistically significant, indicating that most of the difference happened within the first 3 months. This initial difference could indicate an early creep in the polyethylene metal-back locking mechanism as the polyethylene settles in as a result of weight bearing. This creep in the locking mechanism could also explain the difference in MTPM between the groups, as most of it occurs within the first 3 months. However, we did not find any increase in ME for the polyethylene segment during the follow-up period, indicating that such initial creep did not result in any major deformation of the polyethylene. Over time, the backside wear in the modular group could become a relevant factor, resulting in higher MTPM in the modular group—a difference that would also be interpreted as implant migration using marker-based RSA technique (Peters et al. Citation1992, Feng et al. Citation1994, Wasielewski et al. Citation1994, O’Rourke et al. Citation2002, Dalling et al. Citation2015).

In conclusion, both of the uncemented components in this study showed the expected migration patterns of uncemented tibial components with relatively high initial migration during the first 3 months, followed by gradual stabilization, and good stabilization between the 12- and 24-month follow-up. The monoblock component did particularly well with lower migration, even though this group contained the only subject with a high degree of migration. However, the clinically most important parameter, MTPM beyond 12 months, was not statistically different in the 2 groups. Previous RSA studies have found similar stable migration patterns for the monoblock component (Stilling et al. Citation2011, Wilson et al. Citation2012, Henricson et al. Citation2013), and we suggest that this difference should be attributed to the different mechanical properties of the implants, as the monoblock component is more flexible—which improves load sharing and weight distribution in the tibial bone. Alternatively, the difference between the groups could be attributed to initial creep in the polyethylene metal-back locking mechanism of the modular group.

MRA included patients in the study, analyzed RSA radiographs, data interpretation, and statistics, and wrote the manuscript. TL performed surgery and assisted with patient inclusion. NW, HS, GF and MMP planned, initiated and supervised the study. All authors revised and approved the submitted manuscript.

We thank Haakan Lejon for technical assistance with analysis of RSA X-rays. This study was supported by institutional grants from Zimmer and Gentofte Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark.

No competing interests declared.

- Adalberth G, Nilsson K G, Bystrom S, Kolstad K, Milbrink J. Low-conforming all-polyethylene tibial component not inferior to metal-backed component in cemented total knee arthroplasty: prospective, randomized radiostereometric analysis study of the AGC total knee prosthesis. J Arthroplasty 2000; 15(6): 783–92.

- Albrektsson B E, Ryd L, Carlsson L V, Freeman M A, Herberts P, Regner L, Selvik G. The effect of a stem on the tibial component of knee arthroplasty. A roentgen stereophotogrammetric study of uncemented tibial components in the Freeman-Samuelson knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1990; 72(2): 252–8.

- Babis G C, Trousdale R T, Morrey B F. The effectiveness of isolated tibial insert exchange in revision total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002; 84-A(1): 64–8.

- Catani F, Leardini A, Ensini A, Cucca G, Bragonzoni L, Toksvig-Larsen S, Giannini S. The stability of the cemented tibial component of total knee arthroplasty: posterior cruciate-retaining versus posterior-stabilized design. J Arthroplasty 2004; 19(6): 775–82.

- Dalling J G, Math K, Scuderi G R. Evaluating the Progression of Osteolysis After Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2015; 23(3): 173–80.

- Devlin N J, Parkin D, Browne J. Patient-reported outcome measures in the NHS: new methods for analysing and reporting EQ-5D data. Health Econ 2010; 19(8): 886–905.

- Dunbar M J, Wilson D A, Hennigar A W, Amirault J D, Gross M, Reardon G P. Fixation of a trabecular metal knee arthroplasty component. A prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009; 91(7): 1578–86.

- Engh G A, Koralewicz L M, Pereles T R. Clinical results of modular polyethylene insert exchange with retention of total knee arthroplasty components. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000; 82(4): 516–523.

- Feng E L, Stulberg S D, Wixson R L. Progressive subluxation and polyethylene wear in total knee replacements with flat articular surfaces. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1994; (299): 60–71.

- Gallo J, Goodman S B, Konttinen Y T, Raska M. Particle disease: biologic mechanisms of periprosthetic osteolysis in total hip arthroplasty. Innate Immun 2013a; 19(2): 213–24.

- Gallo J, Goodman S B, Konttinen Y T, Wimmer M A, Holinka M. Osteolysis around total knee arthroplasty: a review of pathogenetic mechanisms. Acta Biomater 2013b; 9(9): 8046–58.

- Graves S E, Davidson D, Ingerson L, Ryan P, Griffith E C, McDermott B F, McElroy H J, Pratt N L. The Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Med J Aust 2004; 180(5 Suppl): S31–S34.

- Hansson U, Ryd L, Toksvig-Larsen S. A randomised RSA study of Peri-Apatite HA coating of a total knee prosthesis. Knee 2008; 15(3): 211–6.

- Henricson A, Linder L, Nilsson K G. A trabecular metal tibial component in total knee replacement in patients younger than 60 years: a two-year radiostereophotogrammetric analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90(12): 1585–93.

- Henricson A, Rosmark D, Nilsson K G. Trabecular metal tibia still stable at 5 years: an RSA study of 36 patients aged less than 60 years. Acta Orthop 2013; 84(4): 398–405.

- Hilding M, Aspenberg P. Postoperative clodronate decreases prosthetic migration: 4-year follow-up of a randomized radiostereometric study of 50 total knee patients. Acta Orthop 2006; 77(6): 912–6.

- Holleyman R J, Scholes S C, Weir D, Jameson S S, Holland J, Joyce T J, Deehan D J. Changes in surface topography at the TKA backside articulation following in vivo service: a retrieval analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015; 23(12): 3523–31.

- Hyldahl H, Regner L, Carlsson L, Karrholm J, Weidenhielm L. All-polyethylene vs. metal-backed tibial component in total knee arthroplasty-a randomized RSA study comparing early fixation of horizontally and completely cemented tibial components: part 1. Horizontally cemented components: AP better fixated than MB. Acta Orthop 2005; 76(6): 769–77.

- Insall J N, Dorr L D, Scott R D, Scott W N. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989; (248): 13–4.

- Jacobs J J, Roebuck K A, Archibeck M, Hallab N J, Glant T T. Osteolysis: basic science. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001; (393): 71–7.

- Karrholm J. Roentgen stereophotogrammetry. Review of orthopedic applications. Acta Orthop Scand 1989; 60(4): 491–503.

- Knutson K, Robertsson O. The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (www.knee.se). Acta Orthop 2010; 81(1): 5–7.

- Linder L. Implant stability, histology, RSA and wear–more critical questions are needed. A view point. Acta Orthop Scand 1994; 65(6): 654–8.

- Lombardi A V, Jr., Berend K R, Adams J B. Why knee replacements fail in 2013: patient, surgeon, or implant? Bone Joint J 2014; 96-B(11 Suppl A): 101–4.

- Nilsson K G, Karrholm J, Ekelund L, Magnusson P. Evaluation of micromotion in cemented vs uncemented knee arthroplasty in osteoarthrosis and rheumatoid arthritis. Randomized study using roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis. J Arthroplasty 1991; 6(3): 265–78.

- Nilsson K G, Karrholm J, Carlsson L, Dalen T. Hydroxyapatite coating versus cemented fixation of the tibial component in total knee arthroplasty: prospective randomized comparison of hydroxyapatite-coated and cemented tibial components with 5-year follow-up using radiostereometry. J Arthroplasty 1999; 14(1): 9–20.

- Noordin S, Masri B. Periprosthetic osteolysis: genetics, mechanisms and potential therapeutic interventions. Can J Surg 2012; 55(6): 408–17.

- O’Rourke M R, Callaghan J J, Goetz D D, Sullivan P M, Johnston R C. Osteolysis associated with a cemented modular posterior-cruciate-substituting total knee design: five to eight-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002; 84-A(8): 1362–71.

- Peters P C, Jr., Engh G A, Dwyer K A, Vinh T N. Osteolysis after total knee arthroplasty without cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992; 74(6): 864–76.

- Pijls B G, Valstar E R, Nouta K A, Plevier J W, Fiocco M, Middeldorp S, Nelissen R G. Early migration of tibial components is associated with late revision: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 21,000 knee arthroplasties. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(6): 614–24.

- Ryd L. Micromotion in knee arthroplasty. A roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis of tibial component fixation. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 1986; 220: 1–80.

- Ryd L, Albrektsson B E, Carlsson L, Dansgard F, Herberts P, Lindstrand A, Regner L, Toksvig-Larsen S. Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis as a predictor of mechanical loosening of knee prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1995; 77(3): 377–383.

- Stilling M, Madsen F, Odgaard A, Romer L, Andersen N T, Rahbek O, Soballe K. Superior fixation of pegged trabecular metal over screw-fixed pegged porous titanium fiber mesh: a randomized clinical RSA study on cementless tibial components. Acta Orthop 2011; 82(2): 177–86.

- Thiele K, Perka C, Matziolis G, Mayr H O, Sostheim M, Hube R. Current failure mechanisms after knee arthroplasty have changed: polyethylene wear is less common in revision surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015; 97(9): 715–20.

- Toksvig-Larsen S, Magyar G, Onsten I, Ryd L, Lindstrand A. Fixation of the tibial component of total knee arthroplasty after high tibial osteotomy: a matched radiostereometric study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1998; 80(2): 295–7.

- Toksvig-Larsen S, Jorn L P, Ryd L, Lindstrand A. Hydroxyapatite-enhanced tibial prosthetic fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000; (370): 192–200.

- Valstar E R, Gill R, Ryd L, Flivik G, Borlin N, Karrholm J. Guidelines for standardization of radiostereometry (RSA) of implants. Acta Orthop 2005; 76(4): 563–72.

- Wasielewski R C, Galante J O, Leighty R M, Natarajan R N, Rosenberg A G. Wear patterns on retrieved polyethylene tibial inserts and their relationship to technical considerations during total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1994; (299): 31–43.

- Wilson D A, Richardson G, Hennigar A W, Dunbar M J. Continued stabilization of trabecular metal tibial monoblock total knee arthroplasty components at 5 years-measured with radiostereometric analysis. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(1): 36–40.