Abstract

Background and purpose — Controversies exist regarding thromboprophylaxis in orthopedic surgery. Using data in the nationwide Norwegian Hip Fracture Register (NHFR) with postoperative death and reoperation in the first 6 months after surgery as endpoints in the analyses, we determined whether the thromboprophylaxis in patients who undergo hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture should start preoperatively or postoperatively.

Patients and methods — After each operation for hip fracture in Norway, the surgeon reports information on the patient, the fracture, and the operation to the NHFR. Cox regression analyses were performed with adjustments for age, ASA score, gender, type of implant, length of surgery, and year of surgery.

Results — During the period 2005–2014, 25,019 hemiarthroplasties as treatment for femoral neck fractures were reported to the registry. Antithrombotic medication was given to 99% of the patients. Low-molecular-weight heparin predominated with dalteparin in 57% of the operations and enoxaparin in 41%. Only operations with these 2 drugs and with known information on preoperative or postoperative start of the prophylaxis were included in the analyses (n = 20,241). Compared to preoperative start of thromboprophylaxis, postoperative start of thromboprophylaxis gave a higher risk of death (risk ratio (RR) = 1.13, 95% CI: 1.06–1.21; p < 0.001) and a higher risk of reoperation for any reason (RR =1.19, 95% CI: 1.01–1.40; p = 0.04), whereas we found no effect on reported intraoperative bleeding complication or on the risk of postoperative reoperation due to hematoma. The results did not depend on whether the initial dose of prophylaxis was the full dosage or half of the standard dosage.

Interpretation — Postoperative start of thromboprophylaxis increased the mortality and risk of reoperation compared to preoperative start in femoral neck fracture patients operated with hemiprosthesis. The risks of bleeding and of reoperation due to hematoma were similar in patients who received low-molecular-weight heparin preoperatively and in those who received it postoperatively.

Elderly patients with hip fractures are a frail group with a high risk of peroperative complications. Vascular events caused by thrombosis are common, and the use of chemical thromboprophylaxis is therefore a well-established routine in the treatment of these fractures. However, the risk of perioperative bleeding is also a major concern for the surgeon. Peroperative bleeding increases both the time of surgery and the postoperative risk of reoperation (Vera-Llonch et al. Citation2006). We must therefore balance the competing risks of thrombotic and hemorrhagic complications to avoid unwanted outcomes.

Whether the prophylaxis should start preoperatively or postoperatively is still controversial (Borgen et al. 2013). In Europe, the use of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) in orthopedics has traditionally started before surgery (Ettema et al. Citation2009), while in North America a higher dose initiated several hours after surgery has been common (Gomez-Outes et al. Citation2012, Lassen et al. Citation2012). A possible way to answer this central issue is by using data from an established registry. By using data in the nationwide Norwegian Hip Fracture Register (NHFR) (Gjertsen et al. Citation2008), we compared the relative effects of preoperative start and postoperative start of thromboprophylaxis, concentrating on mortality and risk of reoperation.

Patients and methods

The NHFR started registration of primary operations and reoperations for all hip fractures in Norway in 2005. Immediately after each operation, the surgeon fills in a 1-page paper form. The form includes information on age, sex, cognitive function, type of fracture (with femoral neck fractures being classified as Garden 1–2 or 3–4), and ASA class (Garden Citation1961). The form also provides information on the chemical thromboprophylaxis given during treatment (whether or not it was used, which drug, dosage, and whether the first dose was given preoperatively or postoperatively). The choice of implants and the surgical technique were left to the discretion of the surgeons at the reporting orthopedic units. Information regarding deceased patients was obtained from Statistics Norway. Compared to the Norwegian Patient Registry, the completeness of primary operations in the NHFR has been found to be 94% for hemiarthroplasties (Havelin et al. Citation2014).

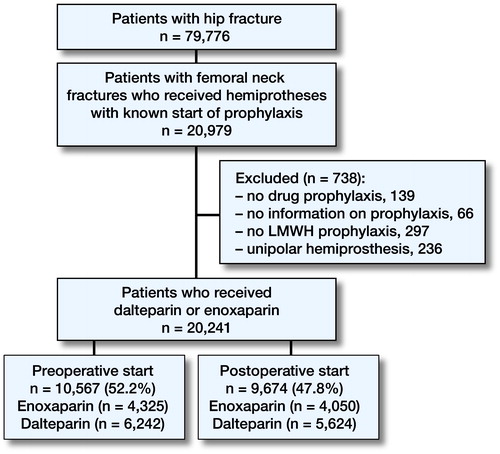

The inclusion and exclusion of patients are summarized in . In the period 2005–2014, 79,776 primary operations for hip fractures were reported to the registry. Femoral neck fractures treated with hemiprosthesis with known start of thromboprophylaxis constituted 20,979 (26.3%) of these operations. In 139 of the operations (0.5%) no thromboprophylaxis was used, and in 66 operations (0.3%) no information on prophylaxis was reported. 12 different types of drugs for prophylaxis were given. Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) predominated entirely, with dalteparin (Fragmin; Pfizer) being used in 57% (14,538 operations) and enoxaparin (Klexane; Sanofi-Aventis) being used in 41% (10,498 operations). In order to obtain an adequately homogenous material for further analysis, only operations with these 2 drugs were included. Furthermore, operations with no information on whether the first dose of the prophylaxis was given preoperatively or postoperatively were excluded (n = 4,284).

Bipolar hemiprostheses constituted 98.8% of the hemiarthroplasties. Operations with unipolar hemiprostheses (236 operations, 1.2%) were therefore excluded to generate a study material that was a fair representation of the modern treatment of hip fractures in Norwegian orthopedic departments.

As a result, 20,241 operations remained for further analysis, with dalteparin being used in 59% (11,866 operations) and enoxaparin in 41% (8,375 operations). Prophylaxis was given preoperatively in 52% (10,567 operations) and postoperatively in 48% (9,674 operations) ().

A reoperation was defined as any secondary surgery following the primary hemiarthroplasty, including closed reduction of a dislocated prosthesis and soft tissue debridement without exchange or removal of prosthesis components.

Standard doses of LMWH, as recommended by the British National Formulary, were defined as 5,000 IU dalteparin or 40 mg enoxaparin. Consequently, half-standard doses were defined as 2,500 IU dalteparin and 20 mg enoxaparin (Heidari et al. Citation2012). To compare the influence of the amount of LMWH given as the initial dose, stratified analyses were performed to compare full dosage and half of standard dosage at preoperative start of the prophylaxis.

As a preoperative start of the thromboprophylaxis could be considered to be more important for those with a rather long preoperative waiting time, separate stratified analyses were performed regarding preoperative waiting time, either with the preoperative waiting time dichotomized (< 24 hours and ≥24 hours) or divided into 5 intervals (≤ 6 hours, > 6 and ≤12 hours, > 12 and ≤24 hours, > 24 and ≤48 hours, and >48 hours).

Statistics

Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression methods. Patients who died or emigrated during follow-up were identified from files provided by Statistics Norway, and the follow-up time for prostheses in these patients was censored at the date of death or emigration. Only the first 6 postoperative months were included in the analyses, as this period was considered most relevant in the present investigation

The Cox multiple regression model was used to compare the relative risk of postoperative death and revision (failure-rate ratios) in patients where the thromboprophylaxis started preoperatively compared to postoperatively, with adjustments for possible influences of sex, age of the patient at surgery, ASA classification, type of fixation (uncemented, cemented with antibiotic-loaded cement, or cemented without antibiotic-loaded cement), and year of surgery. We did not adjust for patients who were operated on both sides, since it has previously been shown that this will not alter the conclusion for the covariates entered (Lie et al. Citation2004). We performed stratified analyses for ASA classes (1–2 or 3–5), type of femoral stem fixation (cemented or uncemented), and preoperative dosage of LMWH (full dosage or half-standard dosage).

Assessments of proportionality in the Cox models were performed using log-minus-log plots of the adjusted survival curves, and the proportionality assumptions were fulfilled. For the statistical analyses, we used IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0 and the statistical package R version 3.0.2 (http://www.R-project.org). Any p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

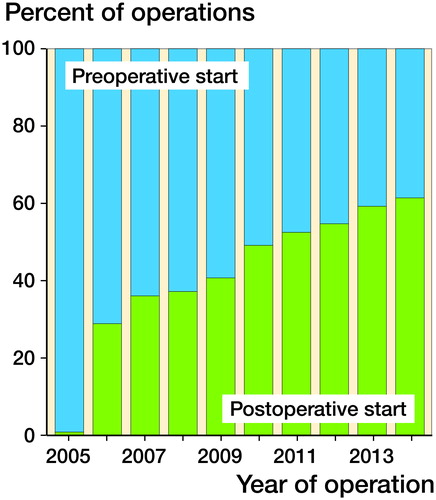

Baseline information regarding the patients is given in . During the study period (2005–2014), postoperative start of thromboprophylaxis became more common ().

Figure 2. The timeline demonstrates the development in start of thromboprophylaxis from 2005–2014 for the patients observed in the study. Femoral neck fractures treated with bipolar hemiarthroplasty with known start of thromboprophylaxis (dalteparin or enoxaparin).

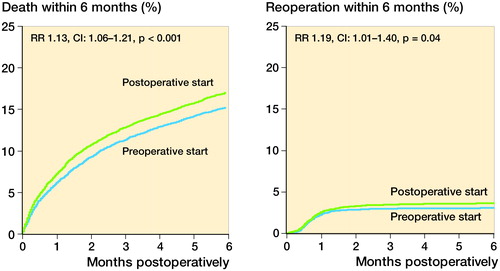

Figure 3. Postoperative mortality and risk of reoperation for patients with femoral neck fractures treated with hemiprostheses.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the patients/operations

Risk of death and reoperation ()

Patients with femoral neck fractures treated with bipolar hemiprostheses (n = 20,241) had a higher risk of death (RR =1.13, 95% CI: 1.06–1.21; p < 0.001) with a postoperative start of prophylaxis than with a preoperative start. A postoperative start also resulted in an increased risk of reoperation for any reason (RR =1.19, 95% CI: 1.01–1.40; p = 0.04) compared to a preoperative start ().

Table 2. Mortality and risk of reoperation 7 days, 30 days and 180 days postoperatively after bipolar hemiarthroplasty due to femoral neck fractures. Cox relative risk ratio (RR) (with preoperative start of prophylaxis as reference) is given with adjustments for possible infl uences of sex, ASA-class, age of the patient at surgery, type of surgery, duration of surgery and year of surgery

When we analyzed the risk of reoperation due to infection, no statistically significant effect of the timing of the start of prophylaxis could be detected (RR =1.25, 95% CI: 0.99–1.57; p = 0.06).

Similar analyses on mortality and risk of reoperation within 7 days postoperatively, within 30 days postoperatively, and within 180 days (6 months) postoperatively were performed (). The increased risk of death proved to be consistent for all 3 intervals in the postoperative period.

Separate analyses on the risk of reoperation due to hematoma did not reveal any statistically significant effect of the timing of the start of prophylaxis (RR =0.7, 95% CI: 0.4–1.2; p = 0.2) ().

Furthermore, intraoperative complications were reported to the registry. 42 of the complications reported were intraoperative bleeding (4.7% of all reported complications). However, there was no difference in the risk of bleeding complications between the patients who had a preoperative start of LMWH (22 bleeding complications) and those who had a postoperative start of LMWH (19 bleeding complications) (RR =0.9, 95% CI: 0.5–1.7; p = 0.7).

Cemented and uncemented hemiarthroplasties

In order to investigate the risk of death and reoperation further, we stratified for the type of femoral stem fixation. Hemiprostheses with antibiotic-loaded cement (n = 14,472) and uncemented hemiprostheses (n = 5,226) gave a higher risk of death with a postoperative start of prophylaxis (). The increased risk of death proved to be consistent at all 3 intervals in the postoperative period (7 days, 30 days, and 180 days).

Table 3. Mortality and risk of reoperation 180 days postoperatively in patients receiving an uncemented and cemented hemiarthroplasty (HA). Cox relative risk ratio (RR) (with preoperative start of prophylaxis as reference) is given with adjustments for possible influences of sex, ASA-class, age of the patient at surgery, duration of surgery and year of surgery

ASA classification

When we assessed the healthiest patient group operated for femoral neck fracture with hemiarthroplasty (ASA 1–2), the benefit of a preoperative start of the prophylaxis was less evident (). For these patients, a postoperative start of LMWH had no effect on the risk of death, reoperation for any reason, or reoperation due to infection or hematoma.

Table 4. Effect of postoperative start of thromboprophylaxis versus preoperative start 180 days postoperatively in healthy patients (ASA 1-2) and in morbid patients (ASA 3-5) with femoral neck fracture operated with bipolar hemiprosthesis. Cox relative risk ratio (RR) (with preoperative start of prophylaxis as reference) is given with adjustments for possible influences of sex, age of the patient at surgery, type of surgery, duration of surgery and year of surgery

For the most morbid patients (ASA 3–5), increased mortality with a postoperative start of thromboprophylaxis was found (). Again, the increased risk of death proved to be consistent for all 3 intervals of the postoperative period. The timing of the start of LMWH did not have a statistically significant effect on the risk of reoperation for any reason or of reoperation due to infection or hematoma.

Dosage of low-molecular-weight heparin

For patients with a preoperative start of thromboprophylaxis, the standard dosage (5,000 IU dalteparin or 40 mg enoxaparin) was given in 51% and half of the standard dosage (2 500 IU dalteparin or 20 mg enoxaparin) was given in 49%. We found no differences in mortality, in the risk of reoperation for any reason, or in the risk of reoperation due to infection or hematoma when the analyses were performed on half-standard dosage and full standard dosage (). All the patients who had a postoperative start of thromboprophylaxis received a full standard dosage.

Table 5. Mortality and risk of reoperation 180 days postoperatively in patients operated with hemiprosthesis with a preoperative start of thromboprophylaxis (n= 9,370) where the primary dose was of full standard (5 000 IU dalteparin or 40 mg enoxaparin) or half standard (2 500 IU dalteparin or 20 mg enoxaparin) dosage. Cox relative risk ratio (RR) (with full dose at start of prophylaxis as reference) is given with adjustments for possible influences of sex, ASA-class, age of the patient at surgery, type of surgery, duration of surgery and year of surgery

Time interval between fracture and operation

The median amount of time elapsed between fracture and start of surgery for hip fracture patients was 21 hours. No independent effect of the preoperative waiting time on the risk of death or reoperation could be detected. Accordingly, the length of time between fracture and operation had no influence on the advantageous effect of a preoperative start of the prophylaxis.

Discussion

The data in our nationwide hip fracture registry showed that a postoperative start of thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin in patients operated with hemiprostheses for femoral neck fracture resulted in higher mortality and higher overall risk of reoperation than with a preoperative start.

In Norway, 99% of the antithrombotic drugs used as prophylaxis for hip fracture patients are low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH): 56% are dalteparin and 43% are enoxaparin. A similar predominance of LMWH has also been reported from the Netherlands (79%) and Denmark (97%) for patients who undergo total hip replacement (Ettema et al. Citation2009, Pedersen et al. Citation2012). Our results are only valid for dalteparin and enoxaparin. However, the benefit of a preoperative start may also be valid for other parenteral and oral antithrombotic compounds that are available.

The trauma of hip fracture activates the coagulation system. The subsequent operation constitutes a second trauma. The process of implanting a hemiprosthesis appears to give more severe trauma than osteosynthesis. Animal studies showed that deaths due to respiratory distress were eliminated when a thrombin inhibitor was administered before induction of the same standard trauma that triggered blood cell aggregation in the lung vessels (Giercksky et al. Citation1976). When the femoral stem is inserted in the femoral canal during hemiarthroplasty, high pressure seems to squeeze procoagulant cell fragments, microparticles, and small molecules such as RNA and histones into the venous system (Dahl et al. Citation2015). The subsequent activation of the coagulation system could be fatal (Pitto et al. Citation1999, Dahl et al. Citation2005, Ettema et al. Citation2008, Talsnes et al. Citation2013). A pressure release hole (diameter 4.5 mm) drilled into the medullary canal at the distal end of the femur appears to reduce the release of tissue factor into the venous system (Engesæter et al. Citation1984). For patients with fracture of the hip and also patients undergoing total hip replacement, chemical thromboprophylaxis has been found to reduce postoperative mortality (Lie et al. Citation2010, Heidari et al. Citation2012, Hunt et al. Citation2013).

Our registry-based cohort was stratified in 2 roughly equal arms of preoperative and postoperative administration of standard doses of LMWH in hip fracture patients. The results showed that a preoperative start reduced fatalities within 6 months of surgery. This favorable effect of preoperative LMWH administration was most pronounced in close relation to surgery. Nevertheless, the preoperative effect was also robust over time and no catch-up effect was noticed during 6 months of observation. Furthermore, a preoperative start of thromboprophylaxis provided a lower risk of reoperation compared to postoperative start. In previous discussions, the risk of reoperation in particular has been brought forward as an argument for starting thromboprophylaxis postoperatively (Lassen et al. Citation2012). This argument was partly based on the fear of perioperative bleeding complicating the surgical intervention. This might also be the explanation for the gradual shift from preoperative to postoperative initiation of LMWH that has been observed during the last decade (). In the present study, no higher risk of intraoperative bleeding nor increased risk of reoperation due to postoperative hematoma could be detected when the prophylaxis was initiated preoperatively.

Patients with symptomatic comorbidity (ASA ≥3) had a higher risk of fatal outcome following a femoral neck fracture than healthier patients (ASA 1 or 2). This result is in accordance with other studies on hip fracture patients, with increased mortality from 1 in 120 to 1 in 30 when the ASA score was 4 rather than 1 (Talsnes et al. Citation2011, Kan et al. Citation2013, Pripp et al. Citation2014). Accordingly, patients with comorbidities appear to benefit more from preoperative LMWH protection than those who are healthy.

The median length of time between fracture and the start of surgery in the present study was only 21 hours. In comparison, 40% of hip fractures in England were operated more than one day after the admission (Bottle et al. Citation2006). Our rather short preoperative interval (from fracture to operation) could be a possible explanation for why we were not able to reveal any independent effect of preoperative delay on the risk of postoperative death or reoperation. Furthermore, the positive effect of a preoperative start shown here, irrespective of the time elapsed between fracture and operation, indicates that peroperative inhibition of the coagulation system is fundamental.

Bone cement to anchor prostheses has been shown to increase mortality close to surgery (Talsnes et al. Citation2013, Pripp et al. Citation2014, Yli-Kyyny et al. Citation2014). In the present study, patients operated with uncemented hemiprostheses also had a higher mortality when the thromboprophylaxis was initiated postoperatively rather than preoperatively. This indicates that insertion of the femoral stem, irrespective of whether cemented or uncemented fixation is used, appears to produce a potent cardiovascular trauma intraoperatively. This would explain why patients operated with either uncemented or cemented hemiprostheses appeared to profit from a preoperative start of the prophylaxis.

A recent paper from England concerning hip fracture patients advocated administration of LMWH in half the dose recommended by the British National Formulary (Heidari et al. Citation2012). This is in keeping with our findings showing no differences in mortality or risk of reoperation whether the initial LMWH dose given preoperatively was half of the standard dose (i.e. 2,500 IU dalteparin or 20 mg enoxaparin) or the full standard dose (i.e. 5,000 IU dalteparin or 40 mg enoxaparin). To conclude, a half-standard dose of LMWH appeared to be a sufficient amount to initiate prophylaxis.

The present study was not a randomized, controlled trial and it may therefore be described as being a hypothesis-generating study. The data in the study were observational, so causality cannot be proven. Nevertheless, to our knowledge this is the first study of its kind to be conducted in this area. Previously published trials have used 2 compounds, mainly the exploratory compound in the postoperative arm and the reference drug (mostly enoxaparin) in the preoperative arm. No trials have compared preoperative and postoperative benefit of the same compound. All the trials reported have been designed to show potentially favorable effects of new regimens compared to well-established regimens. The strength of our study was the inclusion of data from all the surgical units that treat hip fractures in an entire country. Accordingly, the external validity of the results is high. The data regarding the start of LMWH were filled in by the responsible surgeon immediately after surgery. Even though the study had some weaknesses, the results are based on a large number of patients and also consistent reporting of timing of LMWH treatment to the register. Thus, our data strongly indicate that preoperative administration of LMWH to elderly patients undergoing hip fracture surgery with hemiarthroplasty gives fewer fatalities than postoperative administration.

In summary, this study has shown that a postoperative start of LMWH prophylaxis in patients with femoral neck fractures operated with hemiprostheses leads to a higher risk of postoperative death and reoperation than a preoperative start of prophylaxis. There was no significant difference in the risk of bleeding complications or in the risk of reoperation due to hematoma between the patients who had a preoperative start of treatment with LMWH and those who had a postoperative start.

SLS, LBE, and ED performed the statistical analyses. SLS and LBE were mainly responsible for writing the manuscript. All the authors participated in the design of the study, in interpretation of the results, and in development of the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

We thank all the Norwegian orthopedic surgeons who have loyally reported to the Norwegian Hip Fracture Register.

- Bottle A, Aylin P. Mortality associated with delay in operation after hip fracture: observational study. BMJ 2006; 332 (7547): 947–51.

- Dahl O E, Caprini J A, Colwell C W Jr, et al. Fatal vascular outcomes following major orthopedic surgery. Thrombosis and haemostasis 2005; 93(5): 860–6.

- Dahl O E, Harenberg J, Wexels F, Preissner K T. Arterial and venous thrombosis following trauma and major orthopedic surgery: Molecular mechanisms and strategies for intervention. Semin Thromb Hemost 2015; 41: 141–5.

- Engesæter L B, Strand T, Raugstad T S, Husebo S, Langeland N. Effects of a distal venting hole in the femur during total hip replacement. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1984; 103(5): 328–31.

- Ettema H B, Kollen B J, Verheyen C C, Buller H R. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in patients with immobilization of the lower extremities: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Thromb Haemost 2008; 6(7): 1093–8.

- Ettema H B, Mulder M C, Nurmohamed M T, Buller H R, Verheyen C C. Dutch orthopedic thromboprophylaxis: a 5-year follow-up survey. Acta Orthop 2009; 80(1): 109–12.

- Giercksky KE, Bjorklid E, Prydz H. The effect of intravenous injection of purified human tissue thromboplastin in rats. Scand J Haematol 1976; 16(4): 300–10.

- Gjertsen J E, Engesaeter LB, Furnes O, et al. The Norwegian Hip Fracture Register: experiences after the first 2 years and 15,576 reported operations. Acta Orthop 2008; 79(5): 583–93.

- Gomez-Outes A, Terleira-Fernandez A I, Suarez-Gea M L, Vargas-Castrillon E. Dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after total hip or knee replacement: systematic review, meta-analysis, and indirect treatment comparisons. BMJ 2012; 344: e3675.

- Havelin L, Furnes O, Engesæter, LB, Fenstad AM, Dybvik E. Annual report. Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 2014 www.http://nrlweb.ihelse.net/Rapporter/Rapport2014.pdf

- Heidari N, Jehan S, Alazzawi S, Bynoth S, Bottle A, Loeffler M. Mortality and morbidity following hip fractures related to hospital thromboprophylaxis policy. Hip Int 2012; 22(1): 13–21.

- Hunt L P, Ben-Shlomo Y, Clark E M, et al. 90-day mortality after 409,096 total hip replacements for osteoarthritis, from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales: a retrospective analysis. Lancet 2013; 382(9898): 1097–104.

- Kan J W, Kim K J, Lee S K, Kim J, Jeug S W, Choi H G. Predictors of mortality in patients with hip fractures for persons aging more than 65 years old. International Journal of Bio-science and Bio-technology 2013; 5(2): 27–33.

- Lassen M R, Gent M, Kakkar A K, et al. The effects of rivaroxaban on the complications of surgery after total hip or knee replacement: results from the RECORD programme. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012; 94(11): 1573–8.

- Lie S A, Engesaeter LB, Havelin L I, Gjessing H K, Vollset S E. Dependency issues in survival analyses of 55,782 primary hip replacements from 47,355 patients. Stat Med 2004; 23(20): 3227–40.

- Lie S A, Pratt N, Ryan P, et al. Duration of the increase in early postoperative mortality after elective hip and knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92(1): 58–63.

- Pedersen A B, Johnsen S P, Sorensen H T. Increased one-year risk of symptomatic venous thromboembolism following total hip replacement: a nationwide cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012; 94(12): 1598–603.

- Pitto RP, Koessler M, Kuehle J W. Comparison of fixation of the femoral component without cement and fixation with use of a bone-vacuum cementing technique for the prevention of fat embolism during total hip arthroplasty. A prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1999; 81(6): 831–43.

- Pripp A H, Talsnes O, Reikeras O, Engesaeter L B, Dahl O E. The proportion of perioperative mortalities attributed to cemented implantation in hip fracture patients treated by hemiarthroplasty. Hip Int 2014; 24(4): 363–8.

- Talsnes O, Hjelmstedt F, Dahl OE, Pripp AH, Reikeras O. Clinical and biochemical prediction of early fatal outcome following hip fracture in the elderly. Int Orthop 2011; 35(6): 903–7.

- Talsnes O, Vinje T, Gjertsen J E, et al. Perioperative mortality in hip fracture patients treated with cemented and uncemented hemiprosthesis: a register study of 11,210 patients. Int Orthop 2013; 37(6): 1135–40.

- Vera-Llonch M, Hagivara M, Oster G. Clinical and economic consequences of bleeding following major orthopedic surgery. Thromb Res 2006; 117(5): 569–77

- Yli-Kyyny T, Sund R, Heinanen M, Venesmaa P, Kroger H. Cemented or uncemented hemiarthroplasty for the treatment of femoral neck fractures? Acta Orthop 2014; 85(1): 49–53.

- Garden R S. Low-angle fixation in fractures of the femoral neck. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1961; 43-B: 647–63.