Abstract

Background and purpose — Severe backside wear, observed in older generations of total knee replacements (TKRs), led to redesign of locking mechanisms to reduce micromotions between tibial tray and inlay. Since little is known about whether this effectively reduces backside wear in modern designs, we examined backside damage in retrievals of various contemporary fixed-bearing TKRs.

Patients and methods — A consecutive series of 102 inlays with a peripheral (Stryker Triathlon, Stryker Scorpio, DePuy PFC Sigma, Aesculap Search Evolution) or dovetail locking mechanism (Zimmer NexGen, Smith and Nephew Genesis II) was examined. Articular and backside surface damage was evaluated using the semiquantitative Hood scale. Inlays were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to determine backside wear mechanisms.

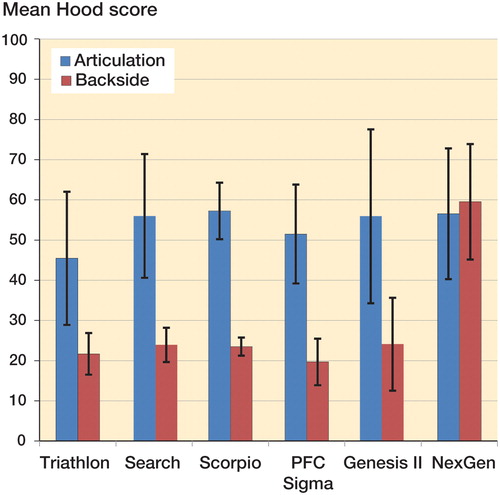

Results — Mean Hood scores for articular (A) and backside (B) surfaces were similar in most implants—Triathlon (A: 46, B: 22), Genesis II (A: 55, B: 24), Scorpio (A: 57, B: 24), PFC (A: 52, B: 20); Search (A: 56, B: 24)—except the NexGen knee (A: 57, B: 60), which had statistically significantly higher backside wear scores. SEM studies showed backside damage caused by abrasion related to micromotion in designs with dovetail locking mechanisms, especially in the unpolished NexGen trays. In implants with peripheral liner locking mechanism, there were no signs of micromotion or abrasion. Instead, “tray transfer” of polyethylene and flattening of machining was observed.

Interpretation — Although this retrieval study may not represent well-functioning TKRs, we found that a smooth surface finish and a peripheral locking mechanism reduce backside wear in vivo, but further studies are required to determine whether this actually leads to reduced osteolysis and lower failure rates.

The use of modular tibial components in fixed-bearing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) enables a precise soft tissue balancing and easier implant removal during revision procedures (Jayabalan et al. Citation2007, Brandt et al. Citation2012a, Citationb). However, micromotion between the polyethylene (PE) inlay and tibial tray can cause wear of the backside of the inlay (Rao et al. Citation2002, Conditt et al. Citation2004a, Citationb, Billi et al. Citation2010). This can lead to release of a high volume of wear debris, subsequent osteolysis, and aseptic loosening.

The extent of inlay micromotions depends on the design of the liner locking mechanism and the surface finish of the tibial tray (Bhimji et al. Citation2010, Billi et al. Citation2010, Berry et al. Citation2012, Brandt et al. Citation2012b, Abdel et al. Citation2014, Holleyman et al. Citation2015). Other factors such as polyethylene manufacturing technique, liner sterilization method, and geometry of the inlay also affect backside wear (Rao et al. Citation2002, Lombardi Jr et al. Citation2008, Azzam et al. Citation2011, Schwarzkopf et al. Citation2015). Since most retrieval studies regarding backside wear involved phased-out implants with older generations of liner locking mechanisms, there are few data regarding the performance of currently used systems (Conditt et al. Citation2004b, Citation2005, Paterson et al. Citation2013, Holleyman et al. Citation2015).

We therefore decided to examine retrieved contemporary fixed-bearing total knee replacements (TKRs) and determine whether design parameters such as the type of locking mechanism, the tibial tray material, and the finish affect the mechanisms and the magnitude of backside damage during service in vivo.

Material and methods

Explanted components

A consecutive series of 102 liners retrieved from fixed-bearing TKRs was examined as part of a retrieval program approved by the institutional bioethics committee (no. 162/12). We included a particular model only when at least 10 pieces with a trackable in vivo service of at least 12 months were available ().

Table 1. Implants included in this study

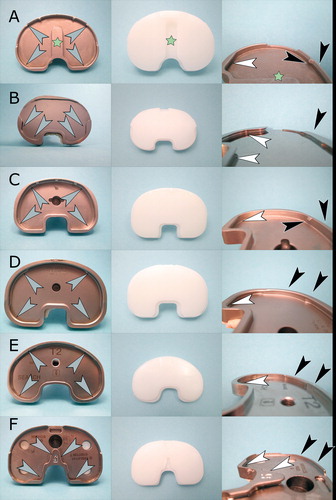

Implants had tibial components of either CoCrMo alloy or titanium alloy, and had 2 styles of liner locking mechanisms that were classified as peripheral locking/peripheral capture mechanisms and dovetail locking mechanisms according to the terms used in the surgical technique manuals of the implants examined ().

Figure 1. Locking mechanisms and inlays examined in this study. A. Triathlon knee: peripheral locking mechanism (gray arrows) with tongue and groove (white arrows) lock and a mechanism incorporating retaining wire held by metal barbs (black arrows). Asterisks indicate the anti-rotational central island. B. Genesis II knee with a dovetail locking mechanism (gray arrows) which incorporates a posterior dovetail (white arrows) and a small anterior wall (black arrows). C. Scorpio knee: peripheral locking mechanism (gray arrows) with tongue and groove (white arrows) lock and a mechanism incorporating retaining wire held by metal barbs (black arrows). D. PFC Sigma knee: peripheral locking mechanism (gray arrows) with anterior and posterior tongue and groove locks (white and black arrows). E. Search knee: peripheral locking mechanism (gray arrows) with anterior and posterior tongue and groove locks (white and black arrows). F. NexGen knee: dovetail locking mechanism (gray arrows) with central dovetail (white arrows) and small anterior wall (black arrows).

The first design includes a 3–4 mm high rim along the circumference of the tray, allowing a snap fit of the inlay by means of a tongue and groove joint localized in the anterior and posterior parts of the rim. In 2 designs (Triathlon, Scorpio), a retaining wire was used in the anterior portion. The dovetail type of mechanism includes a beveled lip within the inlay, which fits into a beveled cut within the posterior wall (3–4 mm in height) of the tibial component, and blocks the inlay against a less pronounced (approx. 2 mm high) anterior metal rim.

The study included 75 female patients and 25 male patients. At revision, their mean age was 68 years, mean BMI was 28, and mean time of implantation was 30 months ( and ).

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of patients included in the study

Table 3. Causes of revision of implants evaluated in the study

Evaluation of backside damage

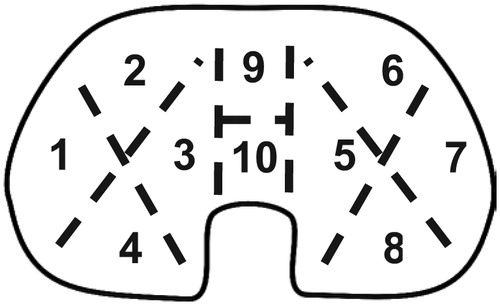

To minimize artifacts related to surgical procedures, all implants were removed using the same technique. After exposure, the liner was removed as the first component: a thin (6–8 mm) osteotome was hammered into the central part of the polyethylene, which was then prised out. This left a characteristic scar, so artifacts caused by surgical tools were easy to distinguish from damage caused by wear. After removal, metal parts were autoclaved and inlays were sterilized by soaking in 10% formaldehyde for 48 hours, drying, and evaluation using an optical microscope at 10–40× magnification. Damage within the articulating surface and backside was measured using a semiqiantitative damage-scoring system developed by Hood et al. (Citation1983). Briefly, each side of the inlay was divided into 10 sectors (), which were then evaluated for the presence of 7 modes of damage: surface deformation, pitting, embedded third bodies, scratching, burnishing (polishing), abrasion, and delamination; each type of damage was recognized according to an atlas published by Harman et al. (Citation2011). Each mode of damage was graded as 0–3 points depending on the area of each sector where it was present (no damage, less than 10% damege, 10–50%, and over 50%, respectively). Inlays were examined by 2 independent observers (ŁŁ and PK) twice with an interval of 1 week, to determine intraobserver and interobserver variability.

Figure 2. The articular and backside of the inlay was divided into sectors for wear evaluation according to the Hood scale.

For each type of implant, 1 unused inlay and 3 used inlays with representative signs of backside wear were examined in low-vacuum mode using an Inspect S Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) (FEI Europe B.V., Eindhoven, the Netherlands) to evaluate mechanisms of polyethylene wear.

A contact profilometer with Hommel-Etamic Turbo Wave v. 7.36 software (Hommel, Teplice, Czech Republic) was used to measure the roughness of the surface of the tibial trays on the medial and lateral condyle. Roughness was measured over a distance of 5 mm in 3 directions: the coronal plane, the horizontal plane, and at an angle of 45 degrees to both of these planes. The results were then averaged. Care was taken not to measure areas of the trays that had been scratched or damaged by surgical tools during implant extraction.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was done using Statistica 12 software. First, we verified the quality of wear scoring: intraclass correlation coefficient (two-way model, absolute agreement) was used to evaluate intraobserver agreement, and Cohen’s weighted kappa was used to verify intra- and interobserver agreement. Normality of distribution of data in all groups was verified using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and Spearman and Pearson tests were used to evaluate correlation between wear scores. Differences within groups were evaluated using two-sided t-test and Wilcoxon test, while differences between multiple groups were evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test with post-hoc multivariative analysis.

Results

Intra- and interobserver agreement; patient characteristics

Good intraobserver agreement in 2 evaluations was found. For articulating surface wear, the intraclass correlation coefficients were 0.965 (CI: 0.949–0.976) and 0.968 (CI: 0.953–0.978) and Cohen’s weighted kappa values for observers ŁŁ and PK were 0.809 (CI: 0.780–0.837) and 0.731 (CI: 0.687–0.775), respectively. For backside wear scores, the intraclass correlation coefficients were 0.968 (CI: 0.953–0.979) and 0.937 (CI: 0.906–0.958), and Cohen’s weighted kappa values were 0.743 (CI: 0.694–0.793) and 0.746 (CI: 0.691–0.800) for observers ŁŁ and PK, respectively. Interobserver agreement was very good for both articulating side score and backside damage score, with Cohen’s weighted kappa values of 0.750 (CI: 0.709–0.790) and 0.770 (CI: 0.718–0.822). There were no statistically significant differences between the demographic data for all 6 implant groups (mean age, BMI, and duration of implantation).

Semiquantitative evaluation of wear

Damage scores for articular surfaces of the inlays were similar in all implants; there were no statistically significant differences (Kruskal-Wallis test) between the designs included. Backside wear characteristics differed between the various designs, with polishing being the predominant mechanism in PFC Sigma and Search knees, surface deformation in Scorpio and Triathlon knees, and burnishing in Genesis II and Zimmer NexGen knees. All implant types except the NexGen knee had similar backside damage scores (with no statistically significant difference between designs). In these designs backside wear scores were also significantly lower than articular surface scores (Genesis: Wilcoxon’s test, p = 003; Triathlon, Scorpio, PFC Sigma, and Search: two-sided t-test, all p < 0.001).

In the NexGen group, backside damage scores were higher (Kruskal-Wallis test) than for the Triathlon (p < 0.001), Genesis (p = 0.001), Scorpio (p = 0.02), PFC Sigma (p < 0.001), and Search (p = 0.02) prostheses ().

Figure 3. Mean Hood scores of articulating side and backside observed in different types of implants. Data were averaged from measurements performed by both observers. Whiskers show SD.

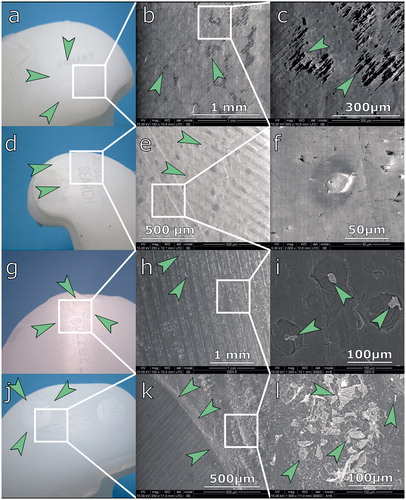

Figure 4. Analysis of backside wear using optical microscopy (left) and scanning electron microscopy (right). a. Arrows indicate dimpling seen in the Triathlon inlay. b. Triathlon knee, low-magnification SEM. Arrows indicate loss of machining marks. c. Triathlon knee, high-magnification SEM. There are no PE particles visible; arrows indicate partially preserved machining marks. d. Flattening (arrows) of machining marks on the Search inlay. e. Search inlay, low-magnification SEM. Arrows indicate loss of machining marks. f. Search inlay, high-magnification SEM. PE flattening (arrows); no particles visible. g. Genesis II inlay. Arrows indicate flattening of machining marks. h. Genesis II, low-magnification SEM. Flattening of machining marks; arrows indicate craters. i. Genesis II, high-magnification SEM image. Arrows indicate PE debris visible within craters. j. NexGen knee. Unworn PE within screw holes of the tibial tray (arrows) and material abrasion around it. k. NexGen knee, low-magnification SEM. Abrasion grooves and border (arrows) of unworn material. l. multiple wear debris seen within abrasion grooves (indicated by arrows).

There was a correlation between damage scores in the articulating part and backside in the NexGen (Pearson’s test, r = 0.07, p < 0.05), Search (Pearson’s test, r = 0.78, p < 0.05), and Genesis (Spearman’s test, R = 0.92, p < 0.05) knees. There was no correlation between wear scores and in vivo service time, BMI, or height of the inlay. In addition, we did not observe any significant differences between damage scores in posterior stabilized and cruciate retaining inlays, or between genders.

Microscopic analysis ()

Optical microscopy and SEM studies revealed differences between backside wear mechanisms in various implant designs. In knees with a peripheral locking mechanism and a rough tibial tray (Scorpio and Triathlon), we observed dimpling of the surface—with partially preserved machining marks seen in SEM images. In implants with a relatively smooth surface on the tibial tray and peripheral snap-fit mechanism (PFC Sigma and Search), we observed flattening of machining marks and a polished appearance of the inlay. We did not find any polyethylene wear particles resulting from abrasion in any of the implants with a peripheral locking mechanism.

Discussion

Previous studies have found that in fixed-bearing TKRs, backside wear can generate substantial amounts of particulate polyethylene debris. Some authors have estimated that the average volume of particles released can be as high as 100–138 mm3 per year; such wear rates would be considered severe in total hip arthroplasty (Li et al. Citation2002, Conditt et al. Citation2004a, Citationb, Citation2005, Billi et al. Citation2010). Mechanical studies have shown that fretting between the PE inlay and tibial tray plays a pivotal role in backside wear, and retrieval studies have identified several variables that affect micromotion of the inlay such as metal surface finish, implant design, and locking mechanism (Li et al. Citation2002, Engh et al. Citation2009, Billi et al. Citation2010, Berry et al. Citation2012, Brandt et al. Citation2012b, Abdel et al. Citation2014, Holleyman et al. Citation2015). It has been found that oxidative stability of polyethylene is related to sterilization technique and can affect backside wear (Muratoglu et al. Citation2003, Jayabalan et al. Citation2007, Lombardi Jr et al. Citation2008, Wu et al. Citation2012, MacDonald et al. Citation2013). Consequently, new generations of locking mechanisms that reduce liner micromotion were introduced (Conditt et al. Citation2004b, Citation2005, Berry et al. Citation2012, Brandt et al. Citation2012a, Citationb, Holleyman et al. Citation2015). There have, however, been few data from retrieval studies to determine how these mechanical improvements affect backside wear rates (Bhimji et al. Citation2010, Holleyman et al. Citation2015).

This was the motivation for the present study, which has shown that in contemporary TKRs, backside damage is reduced in implants with peripheral locking mechanisms and designs featuring a dovetail liner lock and a smooth surface finish.

Although our study included a relatively large number of samples, it had limitations in several ways. Since we examined implants that had failed for various reasons, our material did not represent a group of well-functioning TKRs; it was also not possible to systematically control variables that potentially affect backside damage. To minimize this, we focused on implant models for which at least 10 retrievals were available and we discarded implants with an in vivo service time of less than 12 months (since it has been shown that in TKRs, most of surface roughening that occurs during this time frame (Scholes et al. Citation2013)). Despite the inherent shortcomings, examination of retrievals has been widely used by other researchers to verify the performance of existing designs, and it is the only method that enables investigation of the mechanisms that lead to implant wear in vivo.

Another limitation is related to the Hood scoring method we used, which allows estimation of articular surface damage or backside damage and has been used in several studies (Hood et al. Citation1983, Grochowsky et al. Citation2006, Scholes et al. Citation2013, Holleyman et al. Citation2015). Although some differences exist between the damage scores presented in this study and in previous papers, several reports have also described higher backside damage scores in the NexGen design (Conditt et al. Citation2004b, Crowninshield et al. Citation2006, Medel et al. Citation2011, Paterson et al. Citation2013). The main drawback of the Hood score is that it does not provide any information regarding polyethylene wear, which is expressed as either gravimetric or volumetric loss of material (Billi et al. Citation2010, Teeter et al. Citation2011, Citation2015, Berry et al. Citation2012, Affatato et al. Citation2013, Engh et al. Citation2013). Due to this limitation, we examined the retrievals using SEM, to determine how damage of each type corresponds to wear mechanisms responsible for the release of polyethylene particles.

Some authors have used a modified Hood scale which allows for a more detailed evaluation of each type of inlay damage (Conditt et al. Citation2004a, CitationBrandt et al. Citation2012a). Although this modified score has shown a weak to moderate correlation with implantation time in older liner designs, this was not confirmed in the case of the newer Genesis II implant (Brandt et al. Citation2012a, Citationb). We did not use the modified scale, because of moderate intraobserver and interobserver agreement in a pilot series of inlays. Another way to potentially increase the precision of damage evaluation is to use photogrammetric techniques (Grochowsky et al. Citation2006, Azzam et al. Citation2011, Harman et al. Citation2011, Medel et al. Citation2011). However, photogrammetry is not fully objective, since it requires manual outlining of damaged areas, which may be a source of inter- and intraobserver differences. Also, it does not provide more information regarding wear, since it is entirely possible that a tibial insert would have a large damaged area without substantial material wear and vice versa.

There are several techniques that allow quantification of polyethylene wear in retrievals, such as direct measurement, 3D scanning, and micro CT, but none of them was feasible in our study (Teeter et al. Citation2011, Citation2014, Citation2015). Direct measurement requires a flat topside reference area, and such a feature is only present in the PFC inlay (Berry et al. Citation2012, Levine et al. Citation2016). Measurement using micro CT is very precise, but it requires complex equipment, custom software, and time-consuming data processing—and has therefore been used in studies involving a much smaller number of samples than in our material (Crowninshield et al. Citation2006, Teeter et al. Citation2011, Citation2014, Citation2015, Engh et al. Citation2013, Paterson et al. Citation2013). Additionally, in a retrieval study, artifacts caused by inlay deformation during extraction must be corrected manually, which is time-consuming and reduces the overall measurement accuracy.

Despite having limitations related to the examination protocol, our data suggest that in fixed-bearing TKRs, backside wear depends on the type of liner locking mechanism_which in turn determines the amount of inlay micromotion. In implants with peripheral locking mechanisms we did not find abrasive wear; instead, material deformation and polyethylene cold flow were seen. This resulted in flattening of machining marks (PFC and Search) or polyethylene dimpling (tray transfer of PE) in other implants (Scorpio and Triathlon) with a rough surface finish (Bhimji et al. Citation2010, Harman et al. Citation2011). In TKRs with a dovetail locking mechanism, we found signs of abrasive wear related to inlay micromotion—mild in the polished Genesis II tray and pronounced in the unpolished NexGen tray, with curved scars and protrusion of material into screw holes caused by wear (Conditt et al. Citation2005).

This is consistent with data from several mechanical studies. Using mathematical models of PE wear and data from retrievals, Levine et al. (Citation2016) demonstrated that multidirectional micromotions (which result in arcuate patterns similar to those observed in NexGen knees) play a critical role in backside wear. Our SEM findings—which suggested differences in the extent of micromotion between designs—were confirmed by Bhimji et al. (Citation2010), who found a higher range of micromotion in implants with a dovetail locking mechanism than in those with peripheral capture mechanisms and demonstrated reduction of micromotion by the central island of the Triathlon knee. In our study, the latter design feature of the Triathlon knee was not associated with reduced backside wear, which was comparable to that for the older Scorpio design (without the central island). Our findings are also consistent with the results of several simulator and retrieval studies, which showed that the tray material has little influence on backside wear (Billi et al. Citation2010), while in some designs a polished tray finish can reduce it (Billi et al. Citation2010, Azzam et al. Citation2011, Brandt et al. Citation2012a, Citationb, Abdel et al. Citation2014).

Some studies have found relationships between backside wear and demographic factors or time of in vivo service (Conditt et al. Citation2004a, Citationb, Citation2005, Brandt et al. Citation2012a, Citationb). We, and some other authors (Azzam et al. Citation2011, Abdel et al. Citation2014, Holleyman et al. Citation2015, 2014), did not find any such correlation. As in other reports, we found no relationship between BMI and the extent of backside damage (Scholes et al. Citation2013, Abdel et al. Citation2014, Holleyman et al. Citation2015). This may seem counter-intuitive, but the lack of any role of BMI and patient weight in backside wear was confirmed in a recent study by Levine et al. (Citation2016) based on mathematical models of polyethylene wear and on data from retrievals. Another factor affecting backside wear is the sterilization method used and oxidative degeneration of polyethylene (Muratoglu et al. Citation2003, Wu et al. Citation2012, MacDonald et al. Citation2013). Although we did not evaluate the oxidative index of retrieved specimens, the fact that inlays were sterilized under neutral conditions and the lack of delamination in retrievals together suggest that oxidative degeneration was not important in our material (Muratoglu et al. Citation2003, Wu et al. Citation2012, MacDonald et al. Citation2013). However, since the present study included various grades of UHMWPE, it is possible that the intrinsic wear resistance of PE influenced backside wear rates of different prosthetic designs, especially in the case of the NexGen knee with a liner made of conventional polyethylene.

The interest in backside wear comes from the fact that it may contribute to release of PE debris, which initiates osteolysis and aseptic loosening (Li et al. Citation2002, Conditt et al. Citation2004b, Citation2005, Lombardi Jr et al. Citation2008, Billi et al. Citation2010). In the present study, SEM examination of the NexGen and Genesis implants indicated the presence of partially abraded polyethylene fragments, with sizes ranging from 20 to 150 μm. Periprosthetic osteolysis is initiated by debris smaller than 10 μm; we therefore hypothesize that the particles observed in our material had a low (if any) osteolytic potential (Green et al. Citation1998, Citation2000, Matthews et al. Citation2000a, Citationb). However, we were unable to verify whether such large debris is actually released from the backside of the implant, since it is possible that continuous abrasion of the PE inlay leads to release of smaller (submicron) particles.

Although the data from our study are insufficient to link the extent of backside damage to progression of osteolysis, given the consistent differences between abrasive wear in various implant types, it is reasonable to expect that reduced or eliminated backside wear (as in all-poly and molded poly-on-metal) reduces rates of loosening due to limited release of wear particles. This is not, however, confirmed by data from joint registries, since all the modular designs included in this study have had comparable failure rates, including the NexGen knee with the highest wear scores (Graves et al. Citation2015, Porter et al. Citation2015, Sundberg et al. Citation2015). Similarly, there is conflicting registry data regarding performance of monoblock implants. Data from the UK and USA have shown slightly better or similar performance and data from Australia have shown no differences between revision rates in all-poly and modular components (with variable performance in the all-poly group); polyethylene-on-metal had lower failure rates than all-poly designs (Mohan et al. Citation2013, Graves et al. Citation2015, Porter et al. Citation2015).

Interestingly, monoblock versions of some of the implants examined in our study have also shown differences in performance compared to their modular counterparts. The all-poly PFC implant showed better performance in one US registry (especially in younger patients) and similar performance in a Swedish report, while according to the UK registry early to medium-term results are similar while long-term data (based on a limited number of cases) indicate better performance (Mohan et al. Citation2013, Porter et al. Citation2015, Sundberg et al. Citation2015). Better results were also found for the Genesis II system, while they were poorer for the all-poly Scorpio tray; interestingly, the all-poly version of the NexGen knee had higher revision rates than the modular version (Graves et al. Citation2015, Sundberg et al. Citation2015)

These conflicting data suggest that although backside wear may contribute to osteolysis, its role in aseptic loosening of fixed-bearing TKRs appears to be limited, since its elimination does not directly translate into reduced failure rates. However, variation in the performance of all-poly designs and the limited amount of data regarding their long-term performance indicate that more research is needed to determine the clinical significance of backside wear in fixed-bearing TKRs.

In summary, our study has shown that in fixed-bearing TKRs, backside damage depends on the type of liner locking mechanism—with peripheral snap mechanism performing better than dovetail. In some designs, it can be reduced by applying a polished finish to the tibial tray. Since our retrievals did not represent a cohort of well-functioning TKRs and the data from our material are insufficient to link the extent of backside wear to progression of osteolysis, we consider that additional studies are required to determine whether reducing backside wear will have an effect on osteolysis and loosening rates.

ŁŁ: main investigator, corresponding author, collection of material, data analysis, study design, and preparation of the manuscript. AM: SEM studies, data analysis, and review of the manuscript. PK: collection of material and data analysis. JM: collection of material, data analysis, and study design. JW: SEM studies, data analysis, and study design. CHŁ: statistical analysis and review of the manuscript. JK: study design, data analysis, and review of the manuscript.

This study was supported by a grant from the Polish National Science Center (DZ 2012/05/D/NZ5/01840)

- Abdel M P, Gesell M W, Hoedt C W, Meyers K N, Wright T M, Haas S B. Polished trays reduce backside wear independent of post location in posterior-stabilized TKAs. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472 (8): 2477–82.

- Affatato S, Grillini L, Battaglia S, Taddei P, Modena E, Sudanese A. Does knee implant size affect wear variability? Tribol Int 2013; 66: 174–81.

- Azzam M G, Roy M E, Whiteside L A. Second-generation locking mechanisms and ethylene oxide sterilization reduce tibial insert backside damage in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26 (4): 523–30.

- Berry D J, Currier J H, Mayor M B, Collier J P. Knee wear measured in retrievals: a polished tray reduces insert wear. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012; 470 (7): 1860–8.

- Bhimji S, Wang A, Schmalzried T. Tibial insert micromotion of various total knee arthroplasty devices. J Knee Surg 2010; 23 (3): 153–62.

- Billi F, Sangiorgio S N, Aust S, Ebramzadeh E. Material and surface factors influencing backside fretting wear in total knee replacement tibial components. J Biomech 2010; 43 (7): 1310–5.

- Brandt J-M, Haydon C, Harvey E, McCalden R, Medley J. Semi-quantitative assessment methods for backside polyethylene damage in modular total knee replacements. Tribol Int 2012a; 49: 96–102.

- Brandt J-M, MacDonald S J, Bourne R B, Medley J B. Retrieval analysis of modular total knee replacements: factors influencing backside surface damage. Knee 2012b; 19 (4): 306–15.

- Conditt M A, Ismaily S K, Alexander J W, Noble P C. Backside wear of modular ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene tibial inserts. J Bone Joint Surg 2004a; 86 (5): 1031–7.

- Conditt M A, Stein J A, Noble P C. Factors affecting the severity of backside wear of modular tibial inserts. J Bone Joint Surg 2004b; 86 (2): 305–11.

- Conditt M A, Thompson M T, Usrey M M, Ismaily S K, Noble P C. Backside wear of polyethylene tibial inserts: mechanism and magnitude of material loss. J Bone Joint Surg 2005; 87 (2): 326–31.

- Crowninshield R D, Wimmer M A, Jacobs J J, Rosenberg A G. Clinical performance of contemporary tibial polyethylene components. J Arthroplasty 2006; 21 (5): 754–61.

- Engh G A, Zimmerman R L, Parks N L, Engh C A. Analysis of wear in retrieved mobile and fixed bearing knee inserts. J Arthroplasty 2009; 24 (6): 28–32.

- Engh Jr C A, Zimmerman R L, Hopper Jr R H, Engh G A. Can microcomputed tomography measure retrieved polyethylene wear? Comparing fixed-bearing and rotating-platform knees. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471 (1): 86–93.

- Graves S, Davidson D, de Steiger R, Lewis P, Stoney J, Tomkins A, et al. Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Annual Report 2015.

- Green T, Fisher J, Stone M, Wroblewski B, Ingham E. Polyethylene particles of a “critical size”are necessary for the induction of cytokines by macrophages in vitro. Biomaterials 1998; 19 (24): 2297–302.

- Green T R, Fisher J, Matthews J B, Stone M H, Ingham E. Effect of size and dose on bone resorption activity of macrophages by in vitro clinically relevant ultra high molecular weight polyethylene particles. J Biomer Mater Res 2000; 53 (5): 490–7.

- Grochowsky J C, Alaways L W, Siskey R, Most E, Kurtz S M. Digital photogrammetry for quantitative wear analysis of retrieved TKA components. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater 2006; 79 (2): 263–7.

- Harman M, Cristofolini L, Erani P, Stea S, Viceconti M. A pictographic atlas for classifying damage modes on polyethylene bearings. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2011; 22 (5): 1137–46.

- Holleyman R J, Scholes S C, Weir D, Jameson S S, Holland J, Joyce T J, et al. Changes in surface topography at the TKA backside articulation following in vivo service: a retrieval analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015; 23 (12): 3523–31.

- Hood R W, Wright T M, Burstein A H. Retrieval analysis of total knee prostheses: a method and its application to 48 total condylar prostheses. J Biomer Mater Res 1983; 17 (5): 829–42.

- Jayabalan P, Furman B D, Cottrell J M, Wright T M. Backside wear in modern total knee designs. HSS J 2007; 3 (1): 30–4.

- Levine R A, Lewicki K A, Currier J H, Mayor M B, Van Citters D W. Contribution of micro-motion to backside wear in a fixed bearing total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Res 2016; DOI: 10.1002/jor.23203

- Li S, Scuderi G, Furman B, Bhattacharyya S, Schmieg J, Insall J. Assessment of backside wear from the analysis of 55 retrieved tibial inserts. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002; 404: 75–82.

- Lombardi Jr A V, Ellison B S, Berend K R. Polyethylene wear is influenced by manufacturing technique in modular TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466 (11): 2798–805.

- MacDonald D W, Higgs G, Parvizi J, Klein G, Hartzband M, Levine H, et al. Oxidative properties and surface damage mechanisms of remelted highly crosslinked polyethylenes in total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop 2013; 37 (4): 611–5.

- Matthews J B, Besong A A, Green T R, Stone M H, Wroblewski B M, Fisher J, et al. Evaluation of the response of primary human peripheral blood mononuclear phagocytes to challenge with in vitro generated clinically relevant UHMWPE particles of known size and dose. J Biomed Mater Res 2000a; 52 (2): 296–307.

- Matthews J B, Green T R, Stone M H, Wroblewski B M, Fisher J, Ingham E. Comparison of the response of primary human peripheral blood mononuclear phagocytes from different donors to challenge with model polyethylene particles of known size and dose. Biomaterials 2000b; 21 (20): 2033–44.

- Medel F J, Kurtz S, Sharkey P, Austin M, Klein G, Cohen A, et al. Post damage in contemporary posterior-stabilized tibial inserts: influence of implant design and clinical relevance. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26 (4): 606–14.

- Mohan V, Inacio M C, Namba R S, Sheth D, Paxton E W. Monoblock all-polyethylene tibial components have a lower risk of early revision than metal-backed modular components: A registry study of 27,657 primary total knee arthroplasties. Acta Orthop 2013; 84 (6): 530–6.

- Muratoglu O K, Ruberti J, Melotti S, Spiegelberg S H, Greenbaum E S, Harris W H. Optical analysis of surface changes on early retrievals of highly cross-linked and conventional polyethylene tibial inserts. J Arthroplasty 2003; 18 (7 Suppl 1): 42–7.

- Paterson N R, Teeter M G, MacDonald S J, McCalden R W, Naudie D D. The 2012 Mark Coventry award: a retrieval analysis of high flexion versus posterior-stabilized tibial inserts. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471 (1): 56–63.

- Porter M, de Gorter J-J, Green M, Gregg P, Price A, Tucker K, et al. National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Irland and the Isle of Man. 12th Annual Report 2015.

- Rao A R, Engh G A, Collier M B, Lounici S. Tibial interface wear in retrieved total knee components and correlations with modular insert motion. J Bone Joint Surg 2002; 84 (10): 1849–55.

- Scholes S C, Kennard E, Gangadharan R, Weir D, Holland J, Deehan D, et al. Topographical analysis of the femoral components of ex vivo total knee replacements. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2013; 24 (2): 547–54.

- Schwarzkopf R, Scott R D, Carlson E M, Currier J H. Does increased topside conformity in modular total knee arthroplasty lead to increased backside wear? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015; 473 (1): 1–6.

- Sundberg M, Lidgren L, Dahl A-W, Robertsson O. Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. Annual Report 2015.

- Teeter M G, Naudie D D, McErlain D D, Brandt J-M, Yuan X, MacDonald S J, et al. In vitro quantification of wear in tibial inserts using microcomputed tomography. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011; 469 (1): 107–12.

- Teeter M G, Milner J S, Naudie D D, MacDonald S J. Surface extraction can provide a reference for micro-CT analysis of retrieved total knee implants. Knee 2014; 21 (4): 801–5.

- Teeter M G, Parikh A, Taylor M, Sprague J, Naudie D D. Wear and creep behavior of total knee implants undergoing wear testing. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30 (1): 130–4.

- Wu J J, Augustine A, Holland J P, Deehan D J. Oxidation and fusion defects synergistically accelerate polyethylene failure in knee replacement. Knee 2012; 19 (2): 124–9.