Abstract

Background and purpose — Hemiarthroplasty (HA) is the most common treatment for displaced femoral neck fractures in many countries. In Norway, there has been a tradition of using the direct lateral surgical approach, but worldwide a posterior approach is more often used. Based on data from the Norwegian Hip Fracture Register, we compared the results of HA operated through the posterior and direct lateral approaches regarding patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and reoperation rate.

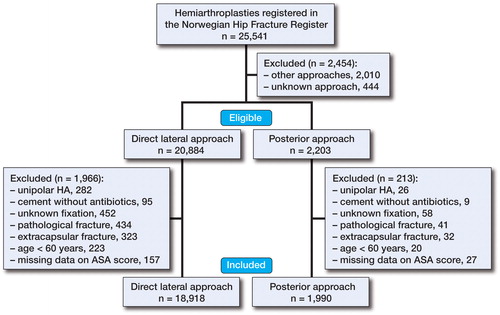

Patients and methods — HAs due to femoral neck fracture in patients aged 60 years and older were included from the Norwegian Hip Fracture Register (2005–2014). 18,918 procedures were reported with direct lateral approach and 1,990 with posterior approach. PROM data (satisfaction, pain, quality of life (EQ-5D), and walking ability) were reported 4, 12, and 36 months postoperatively. The Cox regression model was used to calculate relative risk (RR) of reoperation.

Results — There were statistically significant differences in PROM data with less pain, better satisfaction, and better quality of life after surgery using the posterior approach than using the direct lateral approach. The risk of reoperation was similar between the approaches.

Interpretation — Hemiarthroplasty for hip fracture performed through a posterior approach rather than a direct lateral approach results in less pain, with better patient satisfaction and better quality of life. The risk of reoperation was similar with both approaches.

During the past decade, there has been a change in the treatment of femoral neck fractures from internal fixation to more use of hemiarthroplasty (HA) in many countries (Parker et al. Citation2002, Keating et al. Citation2006, Frihagen et al. Citation2007, Gjertsen et al. Citation2010, Stoen et al. Citation2014). One important issue when treating patients with HA is the type of surgical approach. Two different surgical approaches have predominated. In the transgluteal direct lateral approach, as described by Hardinge (Citation1982), the anterior portion of the gluteus medius and minimus muscles is divided. The posterior approach, as described by Moore (Citation1957), involves division of the piriformis, obturator internus muscle, and gemelli tendons. In Norway, the direct lateral approach has been the most common surgical approach when treating elderly patients with femoral neck fractures (Havelin et al. Citation2016).

For total hip arthroplasty (THA) in osteoarthritis patients, one recent study by Amlie et al. (Citation2014) found worse patient-reported outcome with lower quality of life, more pain, and more limping after the direct lateral approach compared to the posterior approach. To our knowledge, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for the different surgical approaches when treating hip fracture patients with hemiarthroplasty has not been thoroughly investigated. However, in a recently published study by Parker (Citation2015), no significant difference in pain or functional outcomes could be found in 216 patients who were randomized to the lateral or posterior approach.

With this background, we compared the results of the posterior surgical approach and the direct lateral approach regarding patient-reported outcome and reoperation rate in a national setting using data from the Norwegian Hip Fracture Register (NHFR).

Patients and methods

Study design

The NHFR has registered hip fractures on a national basis since 2005. After each primary operation or reoperation, the surgeon fills out a paper form that is sent to the registry. The completeness for primary hemiarthroplasty operations in the NHFR was found to be 91% (Havelin et al. Citation2016). Comorbidity was classified according to the ASA classification. Cognitive impairment was classified as present, not present, or uncertain status. Follow-up questionnaires used for assessing VAS pain from the operated hip (0–100 with 0 meaning no pain and 100 meaning unbearable pain), VAS satisfaction (0–100 with 0 meaning very satisfied and 100 meaning very dissatisfied), EQ-VAS, and EQ-5D-3L were distributed to the patients 4, 12, and 36 months after surgery. The EQ-5D questionnaire has 5 dimensions (walking ability, ability regarding self-care, ability to perform usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression). Preoperative EQ-5D scores were collected retrospectively 4 months postoperatively. We evaluated self-reported walking ability according to the first dimension of the EQ-5D questionnaire in particular. To calculate the EQ-5D index score, a European VAS-based value set was used (Greiner et al. Citation2003).

Patients

On December 31, 2014, a total of 25,541 hemiarthroplasties performed for a hip fracture had been registered in the NHFR. All patients who had undergone hemiarthroplasty surgery through a direct lateral or posterior surgical approach were selected. To have a homogenous group, patients with unipolar prostheses, with cemented prostheses fixed with non-antibiotic-loaded cement, with pathological fractures, with extracapsular fractures, operated with surgical approaches other than posterior or direct lateral, and patients who were <60 years old were excluded (). After exclusion, 20,908 patients remained for analysis. The direct lateral approach group had 18,918 patients and the posterior approach group had 1,990 patients. The patients included had been operated in 52 different hospitals. 36 of these hospitals used one specific approach (direct lateral or posterior) in more than 90% of the operations.

Statistics

PROM data (satisfaction, pain, and quality of life (EQ-5D)) were analyzed and compared between the 2 groups 4, 12, and 36 months postoperatively. The p-values were calculated with general linear models (GLMs) adjusted for cormobidity (ASA class), cognitive function, and fixation of prosthesis.

To evaluate the patients’ walking ability, the first dimension of EQ-5D-3L, describing mobility problems, was explored. Adjustments for differences in fixation technique between the 2 approaches were not possible to perform, as walking ability was a categorical variable. Separate analyses were therefore performed for uncemented and cemented prostheses.The Pearson chi-square test was used for comparison of categorical variables and Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables in independent groups. Patients were followed until time of death, time of emigration, or until the end of the study.

Prostheses survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The Cox regression model was used to calculate relative risk (RR) of reoperation with adjustment for age, sex, comorbidity (ASA class), cognitive function, fixation of the prosthesis, and operation time in the 2 treatment groups. Furthermore, the Cox model was used to construct adjusted survival curves. Also, for risk of reoperation, subanalyses were performed for cemented and uncemented prostheses separately. The proportional hazards assumption was fulfilled when investigated visually using a log-minus-log plot. However, the survival curves crossed each other for prosthesis survival after 8.5 years. The Cox survival analysis was therefore terminated at 8 years of follow-up. A competing risks analysis was also performed using the Fine and Gray (Citation1999) model. The mortality in the study period was set as the competing risk for revision of the prosthesis, and adjustments were done for possible influence of age, sex, cognitive function, ASA class, operation time, and type of fixation. Adjustment for patients who were operated bilaterally was not performed—in line with the results of a previously study that showed that this would not alter the conclusions (Lie et al. Citation2004). The significance level was set to 0.05. The statistical analyses were performed with the statistical package IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 and the statistical package R (Gray RJ (2010) Cmprsk: Subdistribution Analysis of Competing Risks. https://cran.r-project.org).

Results

shows the baseline characteristics of the patients. There were more uncemented prostheses (57% vs. 25%) and there was shorter duration of surgery (67 min vs. 76 min) in the posterior group than in the lateral group. These differences were statistically significant.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients

shows the implants used in the 2 groups. presents the response rates to the patients’ questionnaires. The overall response rate varied from 54% to 58%. Only completed forms were included in the final analysis.

Table 2. Types of implants

Table 3. Response rates for patient questionnaires. The number of posted and returned questionnaires at each follow-up

PROM data

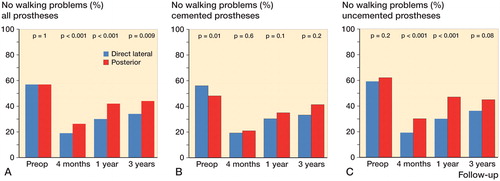

shows that patients reported more pain from and less satisfaction with the operated hip after the direct lateral approach than after the posterior approach. The results were statistically significantly different after 4, 12, and 36 months. Better quality of life (EQ-VAS and EQ-5D index score) was found with the posterior approach, but with statistically significant differences only after 12 months. The patients’ walking ability was similar between the groups preoperatively. At all postoperative follow-ups, patients reported having statistically significantly more walking problems in the direct lateral group than in the posterior group (). Subanalyses for cemented and uncemented prostheses separately showed statistically significantly better walking ability for patients who were operated with the posterior approach in the uncemented group, after 4 and 12 months. Patients operated with an uncemented prosthesis through the posterior approach also reported better walking ability preoperatively ().

Figure 2. Walking ability. The bars show the percentage of patients in each treatment group who reported no problems with walking in the first dimension of EQ-5D at different follow-ups.

Table 4. Patient-reported outcome measures. Results are presented as mean values and as mean differences between direct lateral approach (DLA) and posterior approach (PA) at the different follow-ups

Reoperations

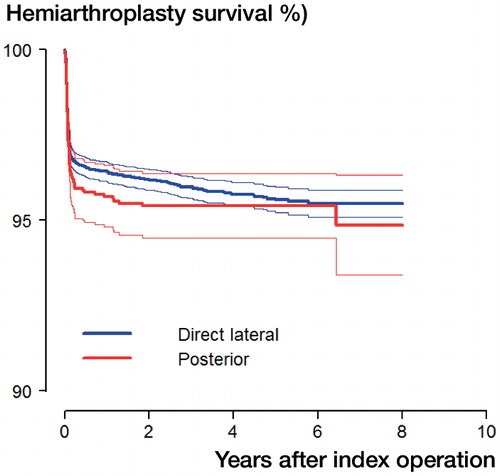

There were more reoperations after the posterior approach than after the direct lateral approach. 1-year prostheses survival was 96% for the direct lateral approach and 95% for the posterior approach. After 8 years, the prostheses survival was 96% after the direct lateral approach and 93% after the posterior approach. is a plot of implant survival, with adjustment for age, sex, cognitive function, ASA class, fixation of the prosthesis, and operation time. The risk of reoperation was similar in the first 8 years irrespective of which approach was originally used (RR =1.2, 95% CI: 0.92–1.4; p = 0.2). Additional analyses with adjustment also for stem fixation gave similar results (RR =1.2, 95% CI: 0.99–1.5; p = 0.07). The analyses using the Fine and Gray competing risk model gave a subhazard rate ratio (subHRR) of 1.16 (95% CI: 0.94–1.4; p = 0.2). Hence, the competing risk approach did not alter the results that had already been obtained using the Cox regression model. Subanalyses showed similar results for the approaches when cemented prostheses (RR =1.0, 95% CI: 0.8–1.5) and uncemented prostheses (RR =1.2, 95% CI: 0.9–1.6) were analyzed separately.

Discussion

Patients operated with hemiarthroplasty using the posterior approach had less pain, were more satisfied, and had a better quality of life than those operated with direct lateral approach. In addition, a larger group of those operated with the posterior approach had fewer walking problems postoperatively.

A study performed by Amlie et al. (Citation2014) found more pain, less satisfaction, poorer life quality, and twice the risk of limping after primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) performed with the direct lateral approach rather than the posterior approach (Amlie et al. Citation2014). These findings are supported by another registry-based study that found less residual pain and greater satisfaction after elective THAs performed with the posterior approach than after elective THAs performed with direct lateral approach (Lindgren et al. Citation2014). The results of the present study on hemiarthroplasty support the findings of these 2 studies regarding pain, satisfaction, and walking ability.

In an observational study with a 1-year follow-up, Leonardsson et al. (Citation2016) reported better patient-reported outcome after the posterior approach than after the direct lateral approach. After adjusting for age, sex, cognitive impairment, and ASA grade, however, no statistically significant results were found. The lower number of patients in that study compared to our study may explain the lack of statistically significant differences.

Parker et al. performed meta-analyses to find a preferred approach for hemiarthroplasties since the 1990s, without being able to come to any firm conclusions (Keene and Parker Citation1993, Parker and Pervez Citation2002). In a recently published randomized, controlled trial involving 216 patients with hip fractures treated with HA, performed either with a lateral or a posterior approach, no differences could be found regarding residual pain or regain of walking ability (Parker Citation2015). Biber et al. (Citation2012) conducted a retrospective study on 704 patients in 2012 and concluded that there was no difference between the posterior approach and the direct lateral approach regarding early surgical complications. However, the posterior approach predisposed to dislocation whereas the direct lateral approach predisposed to hematoma. Rogmark et al. (Citation2014) found that the posterior approach clearly increased the risk of reoperation due to dislocation. Rogmark’s study included patients from both the Norwegian and the Swedish national registries. Although there was a similar tendency, no statistically significant difference was found in the present study involving only patients from the Norwegian Register, probably due to the lower number of patients in the posterior approach group.

Other studies have found a greater risk of reoperation with uncemented prostheses (Langslet et al. Citation2014, Rogmark et al. Citation2014). Langslet et al. showed better 5-year results for uncemented prostheses regarding Harris hip score. In the present study, there was more use of uncemented implants in the posterior group than in the direct lateral group (57% vs. 25%). There is a possibility that patients treated with uncemented stems are a selected extra-fit group. To minimize the risk of confounding, we adjusted the p-values for PROM data for differences in stem fixation. Subanalyses on walking ability, performed for uncemented and cemented prostheses, showed a greater difference in favor of the posterior approach with uncemented stems. Furthermore, a similar risk of reoperation was found for the 2 approaches with cemented and uncemented stems.

In Norway, most hospitals have one standard procedure for hemiarthroplasty, including only 1 approach and 1 fixation technique. 36 out of 52 hospitals had more than 90% of the operations performed with only one of the surgical approaches. This finding supports the assumption that 1 standard approach was used for HAs in most hospitals. Accordingly, the risk of surgical selection bias was low.

The strength of our study was the high number of patients included, and the fact that there was a nationwide result showing the outcome that could be expected in an average orthopedic department.

A registry study compares the actual number of patients operated. The 2 groups that we compared were different regarding the numbers of patients (1:10). This increases the risk of type-II error (i.e. failure to reject a false null hypothesis). The skewed distribution in surgical approaches and fixation techniques is difficult to correct for, because this was no randomized study where the patients could be randomized to 1 of the 2 approaches. Our study shows the actual distribution of approaches used for hemiarthroplasty in our country, and one should have this in mind when discussing the results.

It was a weakness that the preoperative PROM (EQ-5D) data were collected retrospectively 4 months postoperatively, but there is no reason to believe that recall bias should be different for the 2 groups. 1 study comparing recalled data and prospective data found only moderate agreement concerning preoperative status of the patients (Lingard et al. Citation2001). In contrast, Howell et al. (Citation2008) found that the correlation between recalled data and prospective data was good. The response rates to the patient questionnaires were low, probably due to high age, considerable comorbidity, and cognitive dysfunction. An earlier study from the registry found that the non-responders were older, were more cognitively impaired, and had a higher degree of comorbidity. The type of operation did not, however, influence the response rate, so there is no reason to suspect a systematic underreporting in 1 of the 2 treatment groups (Gjertsen et al. Citation2008).

In summary, hemiarthroplasty for hip fracture performed through a posterior approach appears to be a safe procedure with less pain, better patient satisfaction, and better quality of life than with the direct lateral approach.

No competing interests declared.

- Amlie E, Havelin L I, Furnes O, Baste V, Nordsletten L, Hovik O, et al. Worse patient-reported outcome after lateral approach than after anterior and posterolateral approach in primary hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (5): 463–9.

- Anaesthesiologists. A S o. New classification of physical status. Anaesthesiology 1963.

- Biber R, Brem M, Singler K, Moellers M, Sieber C, Bail H J. Dorsal versus transgluteal approach for hip hemiarthroplasty: an analysis of early complications in seven hundred and four consecutive cases. Int Orthop 2012; 36 (11): 2219–23.

- Fine J P, Gray R J. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribtion of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999; 94(446): 496–509.

- Frihagen F, Nordsletten L, Madsen J E. Hemiarthroplasty or internal fixation for intracapsular displaced femoral neck fractures: randomised controlled trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2007; 335 (7632): 1251–4.

- Gjertsen J E, Vinje T, Lie S A, Engesaeter L B, Havelin L I, Furnes O, et al. Patient satisfaction, pain, and quality of life 4 months after displaced femoral neck fractures: a comparison of 663 fractures treated with internal fixation and 906 with bipolar hemiarthroplasty reported to the Norwegian Hip Fracture Register. Acta Orthop 2008; 79 (5): 594–601.

- Gjertsen J E, Vinje T, Engesaeter L B, Lie S A, Havelin L I, Furnes O, et al. Internal screw fixation compared with bipolar hemiarthroplasty for treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92 (3): 619–28.

- Greiner W, Weijnen T, Nieuwenhuizen M, Oppe S, Badia X, Busschbach J, et al. A single European currency for EQ-5D health states. Results from a six-country study. The European journal of health economics: HEPAC: health economics in prevention and care 2003; 4 (3): 222–31.

- Havelin L I, Furnes O, Engesaeter L B, Fenstad A M, Johannessen C B, Dybvik E, Fjeldsgaard K, Gundersen T: The Norwegian Arthroplast Register. Annual report 2016. ISBN: 978-82-91847-21-4 ISSN: 1893-8914 2016.

- Hardinge K. The direct lateral approach to the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1982; 64 (1): 17–9.

- Howell J, Xu M, Duncan C P, Masri B A, Garbuz D S. A comparison between patient recall and concurrent measurement of preoperative quality of life outcome in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2008; 23 (6): 843–9.

- Keating J F, Grant A, Masson M, Scott N W, Forbes J F. Randomized comparison of reduction and fixation, bipolar hemiarthroplasty, and total hip arthroplasty. Treatment of displaced intracapsular hip fractures in healthy older patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88 (2): 249–60.

- Keene G S, Parker M J. Hemiarthroplasty of the hip–the anterior or posterior approach? A comparison of surgical approaches. Injury 1993; 24 (9): 611–3.

- Langslet E, Frihagen F, Opland V, Madsen J E, Nordsletten L, Figved W. Cemented versus uncemented hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures: 5-year followup of a randomized trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472 (4): 1291–9.

- Lie S A, Engesaeter L B, Havelin L I, Gjessing H K, Vollset S E. Dependency issues in survival analyses of 55,782 primary hip replacements from 47,355 patients. Statistics in medicine 2004; 23 (20): 3227–40.

- Lindgren J V, Wretenberg P, Karrholm J, Garellick G, Rolfson O. Patient-reported outcome is influenced by surgical approach in total hip replacement: a study of the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register including 42,233 patients. Bone Joint J 2014; 96-B(5): 590–6.

- Lingard E A, Wright E A, Sledge C B. Pitfalls of using patient recall to derive preoperative status in outcome studies of total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83-A(8): 1149–56.

- Leonardsson O, Rolfson O, Rogmark C. The surgical approach for hemiarthroplasty does not influence patient-reported outcome: a national survey of 2118 patients with one-year follow-upa. Bone Joint J 2016; 98-B (4): 542–7.

- Moore A T. The self-locking metal hip prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1957; 39-A (4): 811–27.

- Parker M J. Lateral versus posterior approach for insertion of hemiarthroplasties for hip fractures: A randomised trial of 216 patients. Injury 2015; 46 (6): 1023–7.

- Parker M J, Pervez H. Surgical approaches for inserting hemiarthroplasty of the hip. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2002; (3): CD001707.

- Parker M J, Khan R J, Crawford J, Pryor G A. Hemiarthroplasty versus internal fixation for displaced intracapsular hip fractures in the elderly. A randomised trial of 455 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84 (8): 1150–5.

- Rogmark C, Fenstad A M, Leonardsson O, Engesaeter L B, Karrholm J, Furnes O, et al. Posterior approach and uncemented stems increases the risk of reoperation after hemiarthroplasties in elderly hip fracture patients. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (1): 18–25.

- Stoen R O, Lofthus C M, Nordsletten L, Madsen J E, Frihagen F. Randomized trial of hemiarthroplasty versus internal fixation for femoral neck fractures: no differences at 6 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472 (1): 360–7.