Abstract

Background and purpose — The bone cement market for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in Norway has been dominated by a few products and distributors. Palacos with gentamicin had a market share exceeding 90% before 2005, but it was then withdrawn from the market and replaced by new slightly altered products. We have compared the survival of TKAs fixated with Palacos with gentamicin with the survival of TKAs fixated with the bone cements that took over the market.

Patients and methods — Using data from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register for the period 1997–2013, we included 26,147 primary TKAs in the study. The inclusion criteria were TKAs fixated with the 5 most used bone cements and the 5 most common total knee prostheses for that time period. 6-year Kaplan-Meier survival probabilities were established for each cement product. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to assess the association between bone cement product and revision risk. Separate analyses were performed with revision for any reason and revision due to deep infection within 1 year postoperatively as endpoints. Adjustments were made for age, sex, diagnosis, and prosthesis brand.

Results — Survival was similar for the prostheses in the follow-up period, between the 5 bone cements included: Palacos with gentamicin, Refobacin Palacos R, Refobacin Bone Cement R (Refobacin BCR), Optipac Refobacin Bone Cement R (Optipac Refobacin BCR), and Palacos R + G.

Interpretation — According to our findings, the use of the new bone cements led to a survival rate that was as good as with the old bone cement (Palacos with gentamicin).

Fixation methods for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) implants are cemented, cementless, or a combination (hybrid). The majority of TKAs performed in Scandinavia are cemented (Robertsson et al. Citation2010). Aseptic loosening of the primary TKA is the most common reason for revision (Carr et al. Citation2012, Furnes et al. Citation2014).

The acrylic bone cements are regulated by 2 international standards (Nottrott Citation2010), with current versions ISO-5833-2002 and ASTM F451-08. Complying with the requirements of the standards, which are based on preclinical testing, does not seem to guarantee clinical success. In the past, there have been examples of poor clinical performance of some of the approved bone cements (Espehaug et al. Citation2002). The bone cement Boneloc is perhaps the most prominent case. This product was introduced in the early 1990s, but was withdrawn from the market already in 1995. Short-term studies had revealed poor clinical performance compared to conventional acrylic bone cements (Havelin et al. Citation1995, Suominen Citation1995, Thanner et al. Citation1995, Furnes et al. Citation1997, Markel et al. Citation2001). Generally speaking, the regulatory framework worldwide for medical devices including implants and bone cements has been much less rigorous than that for new drugs (Riehmann Citation2005, Carr et al. Citation2012, Labek et al. Citation2015).

Approximately 20 bone cement products used for TKAs have been reported in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR). Even so, only 5 different high-viscosity polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) bone cement products with antibiotics have been used in over 90% of all the reported TKAs (Furnes et al. Citation2014).

Before 2004, Palacos with gentamicin (Schering-Plough) had a market share of approximately 90% in Norway. This product was the result of a collaboration between Heraeus Kulzer, who produced the cement components, and Schering-Plough, who supplied and added the antibiotic gentamicin. The distributor of the end-product in Scandinavia was Schering-Plough. This bone cement product was seen by many orthopedic surgeons to be the gold standard in this area. In other parts of Europe, Heraeus Kulzer had a collaboration with Merck, and the end-product was distributed by Merck under the name Refobacin Palacos R (Kühn Citation2000). In 1998, Biomet entered a joint venture with Merck, and in 2004 they purchased Merck’s interest, and founded the Biomet Europe Group. Then, in 2005, Heraeus Kulzer decided to self-distribute the bone cement end-product to all territories, and the well-known products Palacos with gentamicin and Refobacin Palacos R were removed from the market (Bridgens et al. Citation2008, Neut et al. Citation2010). Heraeus Kulzer and Biomet then introduced the new products Palacos R + G and Refobacin BCR, respectively.

Both of the companies, Biomet and Heraeus Kulzer, have claimed in the past that their new products are equivalent to their predecessor (Neut et al. Citation2010, KOFA 2011). On the other hand, it has been shown that even small differences in processing and source of substances may influence the end-product, for example the release of gentamicin (Kühn Citation2000). A number of in vitro studies also brought to light various minor differences between the old and new products in the years that followed (Dall et al. Citation2007a and b, Bridgens et al. Citation2008, Kock et al. Citation2008, Neut et al. Citation2010).

With this background, and using data from the NAR, we compared the survival of TKAs fixated with the old Palacos with gentamicin and that of TKAs fixated with the most used bone cement products that took over the market. We also studied deep infection up to 1 year postoperatively, which would include both early postoperative infections and most of the late chronic infections (Tsukayama et al. Citation1996).

Patients and methods

The data were taken from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR), a national registry covering Norway’s approximately 5 million inhabitants, which was founded in 1987 as a hip registry (Havelin et al. Citation2000). In 1994, knee arthroplasty was included in the registry (Furnes et al. Citation2002), and by the end of 2013 approximately 50,000 TKAs had been registered. For the period 1999–2002, 99% of all TKAs and 97% of all TKA revision operations in Norway were reported to the register (Espehaug et al. Citation2006). For the period 2008–2012, an external analysis found a completeness of more than 95% for primary TKA operations and of 89% for TKA revision operations (Furnes et al. Citation2014). The information from each operation is reported using a standardized form filled out by the surgeon on a voluntary basis, and sent by post to the registry. The information collected in the registry includes the date of the operation, the civil registration number of the patient, indication for the procedure, bone cement product (as identified by catalogue numbers from stickers in the cement wrapping), hospital, and prosthesis brand at the catalogue number level. The NAR publishes annual reports with descriptive statistics (http://nrlweb.ihelse.net).

Study sample

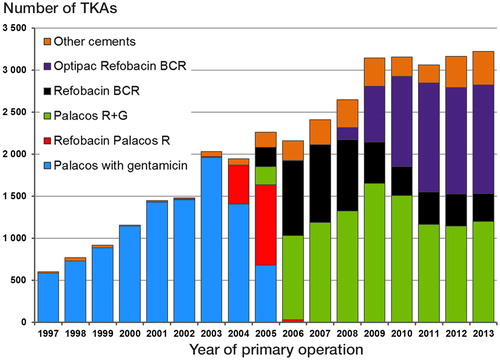

47,503 TKAs were reported to the NAR in the period from January 1, 1997 to December 31, 2013. We excluded TKAs with patellar component (n = 3,205), with unknown diagnosis (n = 103), those uncemented/fixated without antibiotic-loaded bone cement (n = 2,605), and those with unequal proximal and distal bone cement (including hybrid prostheses) (n = 6,018). shows a breakdown of the bone cements used in the remaining TKAs.

Figure 1. Bone cements used for TKAs in Norway in the period 1997–2013. TKAs with patellar component, unknown diagnosis, fixation without antibiotic-loaded bone cement, and hybrid fixation (or unequal bone cement in distal and proximal part) are not included.

In addition, we excluded bone cements used for less than 3 years and in less than 1,000 knees in total (n = 2,846). The remaining bone cements were: Palacos with gentamicin (Schering-Plough), Palacos Refobacin R (Merck), Palacos R + G (Heraeus Kulzer/Heraeus Medical), Refobacin BCR (Biomet), and Optipac Refobacin BCR (Biomet).

TKAs with unequal prosthesis type in the proximal and distal part, or with missing information, were excluded (n = 508). Furthermore, only TKAs with prosthesis brands used over the whole study period (1997–2013) and in over 2,000 knees were included. These criteria left Profix (Smith and Nephew), LCS/LCS Complete (DePuy), AGC (Biomet), and NexGen (Zimmer,) and led to exclusion of 6,057 TKAs. For each of the bone cements, a specific time interval for inclusion was defined, leading to exclusion of 14 other TKAs.

These exclusion/inclusion criteria were used to make the study population as homogeneous as possible regarding the influence of the bone cement product. Maximum possible follow-up was 9 years for the different bone cements, except for Optipac Refobacin BCR, which had only been in use for 6 years (since 2008).

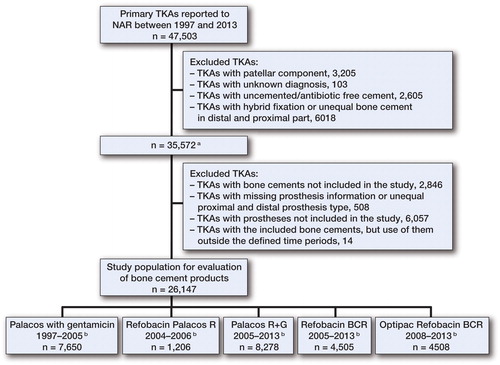

We identified 26,147 TKAs in the total study population for comparison of survival rate according to the bone cement products ( and ).

Figure 2. The selection procedure from the data registered in the NAR. n = number of knees with TKA. a Illustrated in Figure 1.b The time period of use included in study.

Table 1. Inclusion criteria for bone cements and prostheses with product information

In this study, some patients received 2 TKAs and the study population consisted of 20,979 individuals.

Outcome

The outcome variable was prosthesis survival, defined as time from implantation to revision. Revision was defined as exchange, or addition or removal of the implant or part of the implant. Observation times were censored at time of death, emigration, or end of study. Information on death and emigration was obtained from the National Population Registry (TaxAdmin Citation2014) using the civil registration numbers of Norwegian residents.

Predictor

Bone cement product (Palacos with gentamicin, Refobacin Palacos R, Refobacin BCR, Optipac Refobacin BCR, and Palacos R + G) was evaluated as a predictor of prosthesis survival.

Other variables

Adjustment was performed for possible confounding by age (< 60, 60–69, 70–79, > 79), sex, diagnosis (arthrosis, other), and prosthesis brand (LCS/LCS Complete, AGC, NexGen, Profix).

Statistics

6-year survival probabilities with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were established for each bone cement product using the Kaplan-Meier method. Any p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. We used the Cox proportional hazards regression model to assess the association between cement product and revision risk. Unadjusted and adjusted relative revision risk (RR) estimates were established for each bone cement relative to the Palacos R + G, and are presented with CIs and p-values. We also calculated p-values for tests of the overall impact on survival of the cement product. Survival curves were constructed based on the adjusted estimates, and stratified for the different bone cements to illustrate possible differences in the distribution of time from insertion of the prosthesis to revision. Separate analyses were performed with revision for any reason and revision due to deep infection within 1 year postoperatively, as endpoints. The proportional hazards assumption of the Cox model was investigated visually and tested based on scaled Schoenfeld residuals (Ranstam et al. Citation2011), and found to be valid for cements in the analyses with revision for any reason as endpoint (all p > 0.3). With revision due to deep infection within 1 year as endpoint, the assumption was violated for 2 cement products: Palacos with gentamicin (p < 0.001) and Optipac Refobacin BCR (p = 0.03). The residual plot (not shown) and the reported survival curves indicated that analyses performed for different follow-up periods were unlikely to change our conclusions.

Statistical analyses were performed using the software SPSS Statistics version 22.

Results

None of the bone cements had been used over the entire study period. Palacos R + G was the most frequently used bone cement (used in 8,278 knees). Refobacin Palacos R was used in 1,206 knees and was the least used; it also had the shortest period of time in use (3 years). The distribution of age was homogenous for the different cements, with most patients between 60 and 80 years of age. The least used prosthesis/cement combination was the NexGen prosthesis in combination with the cement Palacos with gentamicin (138 knees). The most frequent combination was Optipac Refobacin BCR with LCS Complete (3,304 knees). Over 85% of all the TKAs were done because of osteoarthritis. 75 different hospitals had performed TKAs, and 61 of them had used more than 1 cement product ( and ).

Table 2. Patient and procedure characteristics for the different bone cement products

Survival

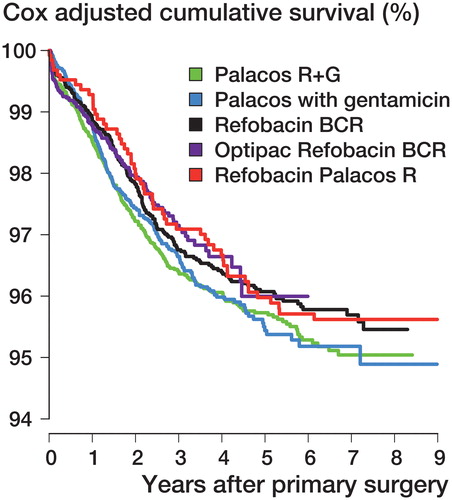

All the bone cements had almost identical results (p = 0.9) with an unadjusted survival percentage of approximately 95% at 6 years. Similar findings were obtained with adjustment for differences in age, sex, diagnosis, and prosthesis brand (p = 0.4) ( and ).

Figure 3. Cox survival curves with cement product as stratification variable for all TKAs with revision for any reason as endpoint. The curves were estimated with adjustment for age, sex, diagnosis, and prosthesis brand.

Table 3. Cox relative revision risk (RR) estimates with revision for any reason as endpoint. Unadjusted and adjusted for age, sex, diagnosis, and prosthesis brand

Infection

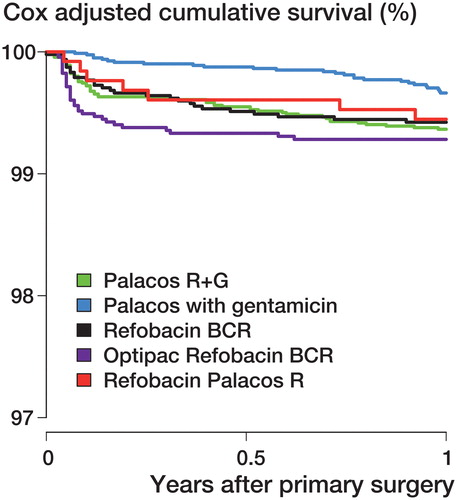

Within one year postoperatively, 147 revisions were done due to deep infection. Compared to Palacos R + G, Palacos with gentamicin had a statistically significantly lower risk of revision due to infection (RR =0.5, CI: 0.3–0.8; p = 0.01). There were no statistically significant differences between the 3 bone cements that are currently on the market (p = 0.7) ( and ).

Figure 4. Cox survival curves with cement product as stratification variable for TKAs with revision due to deep infection within one year postoperatively as endpoint. The curves were estimated with adjustment for age, sex, diagnosis, and prosthesis brand.

Table 4. Cox relative revision risk (RR) estimates with revision due to deep infection within 1 year postoperatively as endpoint. Adjusted for age, sex, diagnosis, and prosthesis brand

Discussion

Summary

We found no statistically significant differences in TKA survival for the bone cements Palacos with gentamicin, Refobacin Palacos R, Palacos R + G, Refobacin BCR, and Optipac Refobacin BCR. Palacos with gentamicin had a significantly lower risk of infections than Palacos R + G. The bone cements currently on the market had practically the same risk of infection 1 year postoperatively.

Other relevant studies

Olerud et al. (Citation2014) performed a consecutive radiostereometric study comparing Refobacin BCR cement with Palacos with gentamicin, which were used in total hip arthroplasty (THA) for 2 patient groups. They studied 51 patients, observing them for 2 years. They found no clinical or statistically significant difference between the 2 cements, and concluded that Refobacin BCR should be safe for clinical use in THAs. However, they also stressed the need for longer follow-up and for results from national registries. Limitations of their study included the short follow-up time (2 years), the lack of randomization, and the length of time between the 2 study groups (due to use of the bone cements in different time periods). Their results may not be transferrable to TKAs.

Kock et al. (Citation2008) conducted in vitro tests of different properties between the "Palacos" cements Refobacin Palacos R and Palacos R + G and the bone cements SmartSet GHV and Refobacin BCR. Their study included handling properties, chemical analysis, and testing according to the ISO standard for acrylic bone cements. Their findings clearly indicated that the copolymers used in the cements SmartSet GHV and Refobacin BCR were different from those used in the 2 "Palacos" cements. They also found differences in viscosity and waiting/hardening times. Since the cement products clearly appeared to be dissimilar, they concluded that clinical data from long-term use of the Palacos cements cannot be extrapolated to Refobacin BCR (and SmartSet GHV).

Neut et al. (Citation2010) compared in vitro gentamicin release from Refobacin Palacos R, Refobacin BCR, Palacos R + G, and SmartSet GHV. All the 3 newer cements showed higher sustained release of gentamicin compared to that from Refobacin Palacos R. They therefore concluded that the gentamicin release characteristics of the old and new cements were different.

Dall et al. (Citation2007a) performed an in vitro comparison of mechanical and handling properties between Refobacin Palacos R and the newer Palacos R + G and Refobacin BCR. All 3 cements were found to have comparable mechanical properties, and to release similar amounts of gentamicin. On the other hand, they found different handling/viscosity curves for the different products, and concluded that these bone cements may perform differently in the operating theater from a surgeon’s point of view.

Dall et al. (Citation2007b) also conducted a study assessing the inter-batch and intra-batch variability in the handling characteristics and viscosity for the cements Refobacin BCR, Palacos R + G, Simplex P Tobramycin, and SmartSet GHV. Refobacin BCR was found to have a different viscosity from Palacos R + G. Their results also suggested that extrinsic factors, such as preparation conditions, may be of more importance than intrinsic variability.

Bridgens et al. (Citation2008) performed an in vitro study comparing Palacos with gentamicin with the cements Palacos R + G and SmartSet GHV. All cements performed well, with minor differences. Regarding the difference between the old and new Palacos cements, they wrote: "We have also shown that the properties of Heraeus Palacos (meaning: Palacos R + G) compared with Schering-Plough Palacos (meaning: Palacos with gentamicin) are different, with superior elution of antibiotics and mechanical characteristics shown by Heraeus Palacos".

Explanations and interpretation

All these studies indicated some minor differences between the old and new bone cements. The new bone cements are almost identical to the old ones, but the small differences may be due to new suppliers of monomers, copolymers, and gentamicin—and/or slightly changed production procedures. Such minor changes in the chemical properties of the ingredients could affect the end-product (Kühn Citation2000, Milner Citation2004, Dall et al. Citation2007a and b). This explanation was also suggested by an official statement from Heraeus Kulzer, given in Bridgens et al. (Citation2008). Furthermore, a legal dispute between Heraeus Medical Nordic and Biomet at the Norwegian Complaints Board for Public Procurement regarding the procurement of cement has indicated that the suppliers of antibiotics and monomers, and also production methods, do actually vary to some extent between the old and new products (KOFA 2011).

Our study has shown that these minor changes did not influence the clinical performance using survival of the TKAs as the outcome measure, but may have influenced other parameters. For example, several of the studies referred to suggest a possibly higher gentamicin release from the bone cements that are currently on the market (Bridgens et al. Citation2008, Neut et al. Citation2010). One hypothesis would be that these properties may lead to fewer deep infections and therefore less septic loosening/revision (Espehaug et al. Citation1997). The present study does not indicate that there may be any clinical effect of a possibly higher gentamicin release. In fact, the old Palacos with gentamicin cement had a statistically significantly lower deep infection rate than the new cements within 1 year postoperatively. We believe that this is a time-dependent effect, and a result of comparison of results from different time periods—as Palacos with gentamicin was stopped in 2005. Other registry-based studies have found an increased risk of revision due to deep infection from around year 2000, and especially after 2005, for THAs (Dale et al. Citation2009, Citation2012). Possible explanations include change in reporting awareness, revision policy, selection of patients, more resistant bacteria, and more modular prostheses. The AGC prosthesis is non-modular, and was used more frequently in the "Palacos with gentamicin" era before 2005. All deep infections of the AGC knee may not have been captured due to the inclusion criteria for revision. The cements currently on the market had practically the same risk of infection 1 year postoperatively.

Another parameter that may be altered is the preparation and the different phases during use (Kühn Citation2000). These properties are of importance to the operator. To our knowledge, almost all cements for TKAs in Norway are prepared with vacuum mixing systems in the operating theaters. The NAR does not have information on the mixing systems used, except for the pre-packaged systems. In our study, we included Optipac Refobacin BCR. This is the same bone cement as Refobacin BCR, but it comes pre-packaged with a closed-vacuum mixing system. Such products may have some advantages—in, for example, reducing the risk of wrong preparation. In the present study, we found no statistically significant differences between these 2 products.

Strengths and limitations

High-powered randomized clinical trials are seldom performed for comparison of rare incidences, such as loosening of cemented TKAs. Large observational studies from arthroplasty registries may therefore provide a good alternative for the study of such events.

The large number of TKAs assessed (26,147), and the fact that potential confounders had been adjusted for in the statistical models, is a strength of the study. Yet, survival of TKAs may also be confounded by other factors such as surgeon experience, patient comorbidities, temperature of the bone cement or of the operating theater, and the use of dissimilar vacuum mixing systems.

A limitation of the study was the short follow-up time. For the Boneloc cement, the chemical properties were dissimilar to those of the standard PMMA bone cements, and revisions started to appear after a short time (Suominen Citation1995, Havelin et al. Citation1995, Furnes et al. Citation1997, Markel et al. Citation2001). With only minor differences between the bone cements investigated in this study, any differences might therefore become apparent after a longer follow-up time.

One flaw might be that the change in the bone cement market in 2005 may have caused confusion for the reporting surgeons as well. All of sudden, the cements had a different name but had packaging of the same color. The registry may therefore contain some minor errors from this period—if the surgeons reported the cement product in writing, instead of using the usual stickers delivered from the company as normally.

Further research

Our study consisted of TKAs only. Whether our result can be extrapolated to—for example—THA remains to be investigated. A longer follow-up period would also be desirable.

Conclusion

We found no difference in prosthesis survival between the bone cement Palacos with gentamicin and the new products introduced after 2005, with this relatively short follow-up time. All the new bone cements included in this study appear to be as good as their predecessor.

ØB performed the analyses and wrote the manuscript. BE supervised the analyses and helped write the manuscript. OF planned the study and helped write the manuscript. LH helped write the manuscript. All the authors contributed to editing of the manuscript, to interpretation of the analyses, and to revision of the manuscript.

No funding was received.

No competing interests declared.

- Bridgens J, Davies S, Tilley L, Norman P, Stockley I. Orthopaedic bone cement: do we know what we are using? J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008; 90 (5): 643–7.

- Carr A J, Robertsson O, Graves S, Price A J, Arden N K, Judge A, Beard D J. Knee replacement. Lancet 2012; 379 (9823): 1331–40.

- Dale H, Hallan G, Hallan G, Espehaug B, Havelin L I, Engesaeter L B. Increasing risk of revision due to deep infection after hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (6): 639–45.

- Dale H, Fenstad A M, Hallan G, Havelin L I, Furnes O, Overgaard S, Pedersen A B, Karrholm J, Garellick G, Pulkkinen P, Eskelinen A, Makela K, Engesaeter L B. Increasing risk of prosthetic joint infection after total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (5): 449–58.

- Dall G F, Simpson P M, Breusch S J. In vitro comparison of Refobacin-Palacos R with Refobacin Bone Cement and Palacos R + G. Acta Orthop 2007a; 78 (3): 404–11.

- Dall G F, Simpson P M, Mackenzie S P, Breusch S J. Inter- and intra-batch variability in the handling characteristics and viscosity of commonly used antibiotic-loaded bone cements. Acta Orthop 2007b; 78 (3): 412–20.

- Espehaug B, Engesaeter L B, Vollset S E, Havelin L I, Langeland N. Antibiotic prophylaxis in total hip arthroplasty. Review of 10,905 primary cemented total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian arthroplasty register, 1987 to 1995. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1997; 79 (4): 590–5.

- Espehaug B, Furnes O, Havelin L I, Engesaeter L B, Vollset S E. The type of cement and failure of total hip replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84 (6): 832–8.

- Espehaug B, Furnes O, Havelin L I, Engesaeter L B, Vollset S E, Kindseth O. Registration completeness in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2006; 77 (1): 49–56.

- Furnes O, Lie S A, Havelin L I, Vollset S E, Engesaeter L B. Exeter and Charnley arthroplasties with Boneloc or high viscosity cement. Comparison of 1,127 arthroplasties followed for 5 years in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop Scand 1997; 68 (6): 515–20.

- Furnes O, Espehaug B, Lie S A, Vollset S E, Engesaeter L B, Havelin L I. Early failures among 7,174 primary total knee replacements: a follow-up study from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1994-2000. Acta Orthop Scand 2002; 73 (2): 117–29.

- Furnes O, Baste V, Krukhaug Y, Kvinnesland I A. Annual report for the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 2014. Helse Bergen HF, Bergen 2014.

- Havelin L I, Espehaug B, Vollset S E, Engesaeter L B. The effect of the type of cement on early revision of Charnley total hip prostheses. A review of eight thousand five hundred and seventy-nine primary arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1995; 77 (10): 1543–50.

- Havelin L I, Engesaeter L B, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Lie S A, Vollset S E. The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register: 11 years and 73,000 arthroplasties. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71 (4): 337–53.

- Kock H J, Huber F X, Hillmeier J, Jager R, Volkmann R, Handschin A E, Letsch R, Meeder P J. In vitro studies on various PMMA bone cements: a first comparison of new materials for arthroplasty. Z Orthop Unfall 2008; 146 (1): 108–13.

- KOFA. The Norwegian Complaints Board for Public Procurement - case 2010/211; 2011 [cited 2015 10.10]. Available from: http://www.kofa.no.

- Kühn K-D. Bone cements. Up-to-date comparison of physical and chemical properties of commercial materials. Springer-Verlag, Berlin 2000.

- Labek G, Schöffl H, Meglic M. New Medical Device Regulations ahead – What does that mean for Arthroplasty Registers? Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (1): 5–6.

- Markel D C, Hoard D B, Porretta C A. Cemented total hip arthroplasty with Boneloc bone cement. J South Orthop Assoc 2001; 10 (4): 202–8.

- Milner R. The development of theoretical relationships between some handling parameters (setting time and setting temperature), composition (relative amounts of initiator and activator) and ambient temperature for acrylic bone cement. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2004; 68 (2): 180–5.

- Neut D, Kluin O S, Thompson J, van der Mei H C, Busscher H J. Gentamicin release from commercially-available gentamicin-loaded PMMA bone cements in a prosthesis-related interfacial gap model and their antibacterial efficacy. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010; 11: 258.

- Nottrott M. Acrylic bone cements: influence of time and environment on physical properties. Acta Orthop Suppl 2010; 81 (341): 1–27.

- Olerud F, Olsson C, Flivik G. Comparison of Refobacin bone cement and palacos with gentamicin in total hip arthroplasty: an RSA study with two years follow-up. Hip Int 2014; 24 (1): 56–62.

- Ranstam J, Kärrholm J, Pulkkinen P, Mäkelä K, Espehaug B, Pedersen A B, Mehnert F, Furnes O. Statistical analysis of arthroplasty data. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (3): 258–67.

- Riehmann M. Regulatory measures for implementing new medical devices. Recalling Boneloc. Dan Med Bull 2005; 52 (1): 11–7.

- Robertsson O, Bizjajeva S, Fenstad A M, Furnes O, Lidgren L, Mehnert F, Odgaard A, Pedersen A B, Havelin L I. Knee arthroplasty in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. A pilot study from the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (1): 82–9.

- Suominen S. Early failure with Boneloc bone cement. 4/8 femoral stems loose within 3 years. Acta Orthop Scand 1995; 66 (1): 13.

- TaxAdmin. This is the National Registry. Tax administration Norway; 2014 [cited 2014 11.6]. Available from: http://www.skatteetaten.no/en/Person/National-Registry/This-is-the-National-Registry/.

- Thanner J, Freij-Larsson C, Karrholm J, Malchau H, Wesslen B. Evaluation of Boneloc. Chemical and mechanical properties, and a randomized clinical study of 30 total hip arthroplasties. Acta Orthop Scand 1995; 66 (3): 207–14.

- Tsukayama D T, Estrada R, Gustilo R B. Infection after total hip arthroplasty. A study of the treatment of one hundred and six infections. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996; 78 (4): 512–23.