Abstract

Background and purpose — To achieve a common understanding when dealing with long bone fractures in children, the AO Pediatric Comprehensive Classification of Long Bone Fractures (AO PCCF) was introduced in 2007. As part of its final validation, we present the most relevant fracture patterns in the lower extremities of a representative population of children classified according to the PCCF.

Patients and methods — We included patients up to the age of 17 who were diagnosed with 1 or more long bone fractures between January 2009 and December 2011 at either of 2 tertiary care university hospitals in Switzerland. Patient charts were retrospectively reviewed.

Results — More lower extremity fractures occurred in boys (62%, n = 341). Of 548 fractured long bones in the lower extremity, 25% involved the femur and 75% the lower leg. The older the patients, the more combined fractures of the tibia and fibula were sustained (adolescents: 50%, 61 of 123). Salter-Harris (SH) fracture patterns represented 66% of single epiphyseal fractures (83 of 126). Overall, 74 of the 83 SH patterns occurred in the distal epiphysis. Of all the metaphyseal fractures, 74 of 79 were classified as incomplete or complete. Complete oblique spiral fractures accounted for 57% of diaphyseal fractures (120 of 211). Of all fractures, 7% (40 of 548) were classified in the category "other", including 29 fractures that were identified as toddler’s fractures. 5 combined lower leg fractures were reported in the proximal metaphysis, 40 in the diaphysis, 26 in the distal metaphysis, and 8 in the distal epiphysis.

Interpretation — The PCCF allows classification of lower extremity fracture patterns in the clinical setting. Re-introduction of a specific code for toddler’s fractures in the PCCF should be considered.

The AO Pediatric Comprehensive Classification of Long Bone Fractures (PCCF) (Slongo et al. Citation2007b) was used in this retrospective clinical study, using the AO Comprehensive Injury Automatic Classifier (AOCOIAC) software (www.aofoundation.org/aocoiac) (Joeris et al. Citation2014). Following a companion paper on fractures of the upper extremity (Joeris et al. Citation2016, also in this issue of Acta Orthopaedica), this paper presents the morphological patterns of fractures of the lower extremity. As in the companion paper, the aim was to describe the most relevant fracture patterns in a representative population of children.

Patients and methods

Patients and methods are described in detail in Part I in this issue (Joeris et al. Citation2016). Patients included were diagnosed with 1 or more long bone fractures between 2009 and 2011 in Lausanne or Bern. The physis of fractured bones had to be open. Standard anterior-posterior (AP) and lateral radiographs were required.

The whole study cohort had 2,716 patients with 2,730 trauma events and 2,840 fractured long bones. For this study, 534 patients who had experienced 542 trauma events leading to 548 fractured long bones in the lower extremity were identified. Patient demographics included age, sex, and BMI. The BMI was only available for patients older than 2 years who were treated at the university hospital in Bern (n = 152).

Statistics

Intercooled Stata software version 12 was used for analysis. Fracture location and child-specific morphological patterns in each location, including both single and combined fractures of the tibia and fibula (hereon referred to as "combined fractures in paired bones") were cross-tabulated with absolute and relative frequencies according to age groups. The distribution of fracture characteristics across age groups was assessed using the chi-square test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Demographics

Patient demographics are given in .

Table 1. Demographics of patients with 548 lower extremity fractures

Fracture location

Of the 548 fractured long bones in the lower extremity, 25% involved the femur and 75% the lower leg (). Of 135 femoral fractures, 69% were shaft fractures. In the lower leg, 53% were isolated tibial fractures (with the fibula being intact). The tibial shaft was mostly affected (55%). Isolated fibular fractures occurred in 13% of the lower extremity fractures (70 of 548); 61 of 70 of these cases were distal epiphyseal fractures.

Table 2. Distribution of fractures according to segment and type within bones. Values are n (%)

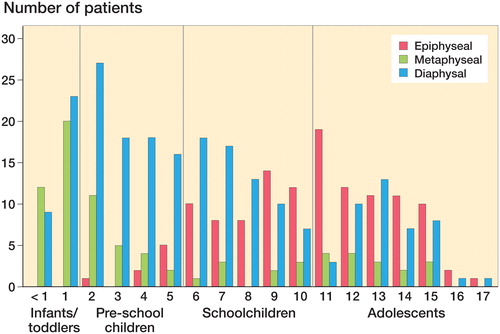

Overall, isolated epiphyseal fractures mainly occurred in schoolchildren and adolescents (94%, 118 of 126). Isolated metaphyseal fracture patterns were mainly diagnosed in infants/toddlers and pre-school children (68%, 54 of 79). Isolated diaphyseal fractures were mostly observed in pre-school children, with a peak at 3 years, then declining gradually until the age of 11 years. Around the age of 13 a second, smaller peak of diaphyseal fractures was observed (Figure). The age-related differences between epiphyseal, metaphyseal, and diaphyseal fractures were statistically significant (p < 0.001).

There was a statistically significantly higher proportion of combined lower leg fractures in adolescents (41%, 61 of 150) than in the remaining patients (24%, 62 of 263) (p < 0.001) ().

Considering 115 combined lower leg fractures with a single fracture location in each bone, combined shaft fractures were the most frequent fracture pattern (Table 3, see Supplementary data). In infants/toddlers and pre-school children, combined fractures of the distal metaphysis in the tibia and fibula were another frequent fracture pattern (19 of 40). Distal epiphyseal fractures of the tibia in combination with distal metaphyseal or epiphyseal fractures of the fibula represented 21% of combined fractures of the tibia and fibula (24 of 115), with 22 of the 24 involving adolescents.

Fracture morphology

93% of all lower extremity fractures (508 of 548) could be classified into 1 of the predetermined child-specific fracture patterns.

Isolated fractures of the lower extremity (femur, tibia, and fi bula), according to age group and fracture location.

Salter-Harris (SH) fracture patterns represented 66% of all isolated epiphyseal fractures (83 of 126) (Table 4, see Supplementary data). Overall, 74 of all 83 SH patterns occurred in the distal epiphysis of the tibia, fibula, and femur. While 15 of 28 SH I fractures occurred in the distal fibula of schoolchildren, the SH II pattern was observed mostly in the distal tibia of adolescents (16 of 38). SH III patterns (n = 11) and SH IV patterns (n = 6) only occurred in schoolchildren and adolescents.

53 of the 79 isolated metaphyseal fractures were classified as incomplete fractures (including torus/buckle or greenstick fractures) (Table 5, see Supplementary data); more than half of these were diagnosed in infants and toddlers (29 of 53) and involved the tibia in 17 of the 29. Furthermore, incomplete fractures accounted for 15 of 53 in pre-school children, involving the tibia in 12 of the 15. Another 21 of the 79 metaphyseal fractures were classified as complete; 10 of these 21 were diagnosed in adolescents.

Of the isolated diaphyseal fractures, complete oblique spiral fractures occurred most frequently (57%, 120 of 211), with pre-school children representing 44% of this fracture pattern (53 of the 120). The tibia was involved in 58% of these fractures (69 of the 120). 29 of the 33 diaphyseal fractures classified as "other" were diaphyseal fractures of the tibia and so-called toddler’s fractures (Table 6, see Supplementary data).

Half of the combined fractures concerning the tibia and fibula occurred in the diaphyseal region (40 of 79), with complete oblique spiral fractures of the tibia accounting for 25 of the 40 (Table 7, see Supplementary data). 24 of 26 combined distal lower leg fractures involving the metaphysis were either combined incomplete or combined complete fractures of the tibia and fibula. All documented combined distal fractures involving the epiphysis had SH I fracture patterns of the fibula (Table 7, see Supplementary data).

Discussion

In this study, long bone fracture patterns in the lower extremity of children represented about 20% of a larger study cohort, including both upper and lower extremity fractures (Joeris et al. Citation2014). Lower leg fractures accounted for 15% of the fractures in this large cohort, a higher percentage than in 2 other recent epidemiological studies—which reported proportions of 4% and 7% (Cooper et al. Citation2004, Hedstrom et al. Citation2010). Most of the lower leg fractures were tibial fractures or combined fractures of the tibia and fibula. Applying the PCCF, we found some distinct age-specific fracture patterns of clinical relevance that had not been described before. For example, epiphyseal fractures of the lower leg were rare in infants/toddlers and pre-school children. It is noteworthy that all fractures of the lower extremity of infants/toddlers and pre-school children were extra-articular.

The occurrence of proximal epiphyseal fractures was rare compared to the occurrence of distal epiphyseal fractures, but similar observations have been made before, during the adaptation of the "SH" classification for epiphyseal fractures (Neer and Horwitz Citation1965, Peterson and Peterson Citation1972, Ogden Citation1981). SH II fractures were confirmed to be the most common type of epiphyseal fracture (Tepper and Ireland Citation2003) and they mostly occurred in adolescents.

The PCCF appeared to be especially comprehensive for metaphyseal and epiphyseal lower extremity fractures (only 4 epiphyseal fractures and only 3 metaphyseal fractures were classified as "other"). However, compared to the upper extremity, where 0.7% of all fractures could not be diagnosed within 1 of the specific child fracture patterns (Joeris et al. Citation2016), 7% of the lower extremity fractures were diagnosed as "other". The majority of "other" fractures were so-called toddler’s fractures (Shravat et al. Citation1996, John et al. Citation1997, Mellick et al. Citation1999), which had been excluded as a separate category (morphology code/3) from the PCCF earlier and included in the category "other" (/9) instead (Slongo et al. Citation2006). This conscious decision was made due to lack of reliability of diagnosis—as it was noticed that using radiographs, surgeons would not be able to reliably distinguish between toddler’s fractures and oblique/spiral fractures in the diaphysis. Following a study in 1999 involving 55 children aged 1–8, it was repeatedly stated that the term toddler’s fracture should be replaced with the term childhood accidental spiral tibial (CAST) fracture, as the fracture was found to involve more the distal half of the tibia instead of the distal third (as originally defined). Another reason was that most spiral tibial fractures occurred in children who were not chronologic toddlers or were not within the originally defined age range of 9–36 months (Mellick et al. Citation1999).

With only 0.7% and 0.8% toddler’s fractures in 2 validation studies, the clinical significance of the toddler’s fracture seemed limited (Slongo et al. Citation2006, Slongo et al. Citation2007a). In this study, 5% of 548 lower extremity fractures were identified to be toddler’s fractures. Although these fractures may be difficult to diagnose from radiographs when very fine or confused with oblique/spiral fractures, the inclusion of a specific category as initially suggested within the PCCF should be reconsidered.

Even so, the PCCF is a classification system that was intensively evaluated during its development process. Reliability and validity parameters regarding fracture location by segment are fully described elsewhere (Audigé et al. Citation2004, Slongo et al. Citation2006, Citation2007a and c), thus making coding by a single experienced surgeon trustworthy. The reliability of the classification according to the child patterns would require further research effort on the basis of this epidemiological description, but this was beyond the scope of this paper.

Our study had limitations—in particular, its retrospective study design, with the same problems for the lower extremity and upper extremity cohorts (Joeris et al. Citation2016, this issue). The quality of data was particularly dependent on the completeness of the patient charts.

Overall, the PCCF showed its usefulness for lower extremity fractures in a large patient cohort. The distribution data presented may be generalized to children in developed countries and may be used for teaching purposes. Compared to the upper extremity, a higher proportion of fractures were classified as "other"—mostly including toddler’s fractures, which lack a specific PCCF fracture code. The effect of this classification on choice of treatment and prognostication of outcomes still needs to be determined in a prospective multicenter study, which would complete the validation of the PCCF.

Supplementary data

Tables 3–7 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2016.1258533.

AJ collected all the clinical data from the Children’s Hospital in Bern, was involved in overall data analysis and interpretation, and contributed to all manuscript drafts. NL collected all the clinical data from the Children’s Hospital in Lausanne, contributed to data analysis, and reviewed the manuscript. AB reviewed all the data, prepared the first draft of the manuscript, and did the final copy editing and formatting. TS was the initiator of the development of the PCCF and AOCOIAC. He was involved in data analysis and interpretation, and reviewed the manuscript. LA was an employee of AO Clinical Investigation and Documentation (AOCID) at the time of data collection and most of the analyses, and was the overall project methodologist and coordinator included in the development and introduction of AOCOIAC in the participating clinics. He was the mentor of AJ during his fellowship at AOCID and supervised the project. He performed most of the data analyses, and participated in preparation of the manuscript.

AJ and AB are employed by AOCID, an institute of the AO Foundation, which is a medically guided not-for-profit foundation. LA declares consultancy payments from AOCID for the completion of this manuscript. NL and TS have nothing to disclose.

IORT_A_1258533_O_supplementary_data.pdf

Download PDF (30.1 KB)- Audigé L, Hunter J, Weinberg A, Magidson J, Slongo T. Development and evaluation process of a paediatric long-bone fracture classification proposal. Eur J Trauma 2004; 30 (4): 248–54.

- Cooper C, Dennison E M, Leufkens H G, Bishop N, van Staa T P. Epidemiology of childhood fractures in Britain: a study using the general practice research database. J Bone Miner Res 2004; 19 (12): 1976–81.

- Hedstrom E M, Svensson O, Bergstrom U, Michno P. Epidemiology of fractures in children and adolescents. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (1): 148–53.

- Joeris A, Lutz N, Wicki B, Slongo T, Audige L. An epidemiological evaluation of pediatric long bone fractures - a retrospective cohort study of 2716 patients from two Swiss tertiary pediatric hospitals. BMC Pediatr 2014; 14: 314.

- Joeris A, Lutz N, Blumenthal A, Slongo T, Audigé L. The AO Pediatric Comprehensive Classification of Long Bone Fractures (PCCF). Part I: Location and morphology of 2,292 upper extremity fractures in children and adolescents. Acta Orthop 2016. [Epub ahead of print]

- John S D, Moorthy C S, Swischuk L E. Expanding the concept of the toddler’s fracture. Radiographics 1997; 17 (2): 367–76.

- Mellick L B, Milker L, Egsieker E. Childhood accidental spiral tibial (CAST) fractures. Pediatr Emerg Care 1999; 15 (5): 307–9.

- Neer C S, 2nd, Horwitz B S. Fractures of the proximal humeral epiphysial plate. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1965; 41: 24–31.

- Ogden J A. Injury to the growth mechanisms of the immature skeleton. Skeletal Radiol 1981; 6 (4): 237–53.

- Peterson C A, Peterson H A. Analysis of the incidence of injuries to the epiphyseal growth plate. J Trauma 1972; 12 (4): 275–81.

- Shravat B P, Harrop S N, Kane T P. Toddler’s fracture. J Accid Emerg Med 1996; 13 (1): 59–61.

- Slongo T, Audige L, Schlickewei W, Clavert J M, Hunter J, International Association for Pediatric Traumatology. Development and validation of the AO pediatric comprehensive classification of long bone fractures by the Pediatric Expert Group of the AO Foundation in collaboration with AO Clinical Investigation and Documentation and the International Association for Pediatric Traumatology. J Pediatr Orthop 2006; 26 (1): 43–9.

- Slongo T, Audige L, Clavert J M, Lutz N, Frick S, Hunter J. The AO comprehensive classification of pediatric long-bone fractures: a web-based multicenter agreement study. J Pediatr Orthop 2007a; 27 (2): 171–80.

- Slongo T F, Audige L, Group A O P C. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium for children: the AO pediatric comprehensive classification of long bone fractures (PCCF). J Orthop Trauma 2007b; 21 (10 Suppl): S135–S60.

- Slongo T, Audige L, Lutz N, Frick S, Schmittenbecher P, Hunter J, Clavert J M. Documentation of fracture severity with the AO classification of pediatric long-bone fractures. Acta Orthop 2007c; 78 (2): 247–53.

- Tepper K B, Ireland M L. Fracture patterns and treatment in the skeletally immature knee. Instr Course Lect 2003; 52: 667–76.