A 72-year-old man with a history of hypertension and hypothyroidism underwent ulnar nerve decompressive surgery at the elbow. 4 days later, the skin around the wound got erythematous and swollen with several small pustules. The patient had no fever but experienced extreme fatigue. Flukloxacillin was prescribed by his general practitioner. No microbial culture was done.

Despite antibiotics, the skin status deteriorated and 1 week after surgery the patient was admitted to hospital with clinical suspicion of abscess. There was edema of the arm, and the skin around the wound was warm and intensely red with multiple small pustules. Serous fluid admixed with pus could be expressed from the edges of the wound. The body temperature was 38.5 °C, saturation 94% on 2 L oxygen, and respiration 12/min. Blood samples showed C-reactive protein (CRP) 156 mg/L and white cell count (WCC) 22 × 109/L. An acute revision of the wound was performed but no tissue necrosis was detected. Microbial cultures were done and flukloxacillin treatment was replaced with intravenously administered cefotaxim (1 g, 3 times daily).

During the days that followed, the area of skin involvement with multiple skin erosions expanded to engage the whole forearm and the distal part of the upper arm. At no point was severe pain registered. The patient developed episodes of fever with body temperature of 40.8 °C accompanied by chills, vomiting, pulse 93/min, blood pressure 170/92 mmHg, respiration 32/min, saturation 87–90% on 2 L oxygen. Bedside chest radiographs showed atelectasis. No pulmonary infiltrates were identified. Inflammatory markers were elevated: CRP 340 mg/L, WCC 72 × 109/L, and differential white blood cell count of neutrophils 32 × 109/L. Blood, urine, and wound cultures—all taken during antibiotic treatment—were repeatedly negative. More precisely, no aerobic/anaerobic bacteria were detected in blood, urine, or wound cultures. No bacteria or fungi were detected with 16S rDNA or 18S rDNA, and tissue biopsies sent for PCR were negative for mycobacterial species.

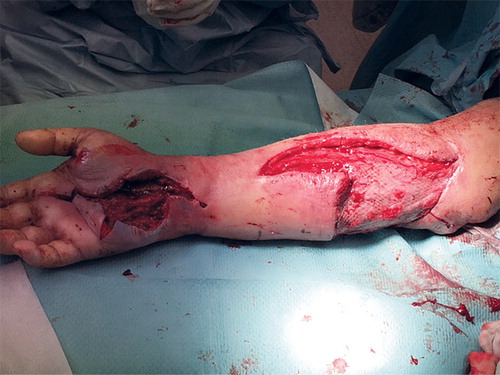

Daily revisions of the wound area were performed in the first 5 days, then another 3 revisions were performed every second day. There was pus and necrosis of the wound edges and subcutaneous fat was seen in the expanding wound, but the fascia was unaffected at the first 4 revisions and histopathology samples showed phlegmonous necrosis of the dermis and subcutis. The dressing used was sterile compresses, bandage, and plaster splint. By the time of the fifth revision, necrosis of the fascia had developed and necrotizing fasciitis was suspected.

Antibiotics were switched to intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam 4 g t.i.d and clindamycin 300 mg t.i.d., and vacuum-assisted therapy was applied. Sympathomimetic drugs were not used, but systemic corticosteroids (betamethasone: first dose 20 mg, thereafter 4 mg daily for 9 days, tapered to zero over 3 days) were given due to respiratory distress. The systemic symptoms declined and the wounds of the arm were closed with a rotation lambeau over the elbow and skin transplants. Donor skin was taken from the thigh, with no impaired healing. The WCC remained elevated (32 × 109/L) but CRP declined to 43 mg/L.

After 3 weeks of hospitalization, the patient was discharged with oral clindamycin therapy. He was re-admitted to hospital 4 days later due to malaise, increased swelling and redness of the whole arm, and small pustules. An abscess in the palm of the hand was drained. Within hours, the patient developed fever, CRP 292 mg/L, and WCC 41 x109/L. Acute revision of the arm and hand revealed necrosis of the subcutaneous fat. Pus was seen below the fascia of the arm and a necrotic triceps tendon was removed (). The need for amputation of the arm was discussed. Blood, urine, and wound cultures remained negative. The patient was transferred to the infectious diseases clinic where meropenem was added to clindamycin.

At this point, the patient had developed a minor wound around the cathéter à demeure at the urethral opening, with pustules in the periphery and swelling, but no erythema. The lesions were initially interpreted by the urologists to be due to a herpes simplex infection. After consultations with specialists in urology, dermatology, pathology, hematology, and infectious diseases, the diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum was suspected. After administering prednisolone 70 mg daily in addition to antibiotic therapy, CRP declined from 232 mg/L to 43 mg/L within 3 days and an improvement of the skin defects was seen, which further supported the diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum (). Follow-up of the elevated WCC was done and an underlying hematological cause of pyoderma gangrenosum was excluded.

Figure 2. After initiation of systemic corticosteroid therapy, the inflammation quickly subsided and a new skin transplant was successful.

B. Partially vital areas of former skin transplant in the forearm, but still new areas with necrosis in the palm.

Discussion

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis and an autoinflammatory disorder. It is an important differential diagnosis to postoperative infections, especially necrotizing fasciitis. Pyoderma gangrenosum often begins as a sterile pustule, evolving rapidly into an ulcer that can be painful, with undermined violaceous borders, surrounding erythema, edema, and a mucopurulent exudate (Wollina Citation2007). The ulcer often expands due to tissue necrosis and the wound can measure up to 30 cm or more. The lesions can be deep, exposing muscles and tendons (Wallach and Vignon-Pennamen Citation2015). The disease is commonly seen on the lower extremities but can occur at any location on the body surface. Extracutaneous manifestations are rare, but the lungs, eyes, genital mucosa, and spleen can be involved. In 50% of the cases, pyoderma gangrenosum is associated with a systemic disease—mainly inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), or hematological disorders (Wollina Citation2007).

Pyoderma gangrenosum can develop spontaneously or can be induced by cutaneous trauma (pathergy) such as surgery, injections, or bites. The phenomenon of pathergy is seen in up to half of the cases (McKee et al. Citation2012). It is an important feature of the disease and when manifested in this context, pyoderma gangrenosum is often misdiagnosed as a postoperative infection and goes largely unrecognized. The clinical course is commonly quiescent with an ulceration of prolonged duration. Fever and general malaise of variable intensity can occur (Wallach and Vignon-Pennamen Citation2015).

The histology of pyoderma gangrenosum is non-specific. A biopsy is, however, always required to exclude other ulcerative conditions such as vasculitis, vascular occlusive diseases, exogenous tissue injuries, drug reactions, infections, and malignancy (Wollina Citation2007). Surgery should be avoided, as debridement leads to a deterioration and extension of the wound. Treatment with systemic corticosteroids and ciclosporin A or TNF-alfa-inhibitors may show a response within days (Patel et al. Citation2015).

Necrotizing fasciitis is an infectious condition with an abrupt onset and an aggressive course, where progression of the lesion is seen within hours. It is usually accompanied by pain that is out of proportion to the clinical lesion. Management of the disease requires prompt surgical debridement. In a retrospective study, the average number of surgical procedures was 3 (Wong et al. Citation2003).

Our patient had a progressive and prolonged course of disease and received 10 surgical revisions altogether. 5 surgical debridements were done before necrosis of the fascia appeared, suggesting that repeated surgery caused involvement of the fascia. In addition, no severe pain was registered. Cultures were repeatedly negative and a non-infectious inflammatory condition should have been suspected. However, all cultures were done during antibiotic treatment and could therefore be regarded as unreliable. Absence of initial signs of fascia involvement, negative cultures, and progression in spite of antibiotic therapy and surgery should raise suspicion of other diagnoses. Involving a dermatologist at this point is of crucial value. After corticosteroid treatment for respiratory problems, the general condition of the patient improved temporarily, which was interpreted as an effect of the antibiotics and wrongly favored the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. Furthermore, a few days after withdrawing the cathéter à demeure, the patient developed pustules and ulcers at the urethral opening. Signs of pathergy at other locations of the body should raise the suspicion of pyoderma gangrenosum. In cases with trauma-induced pyoderma gangrenosum, deterioration of the general condition of the patient, elevated vital parameters, and elevated inflammatory markers can easily be perceived as signs of infection (Wangia et al. Citation2013, Barr et al. Citation2009, Bisarya et al. Citation2011, Utrillas-Compaired et al. Citation2015, Mahajam et al. Citation2005). However, these findings are also seen in non-infectious inflammatory conditions.

Diagnostic clues

Lack of specific diagnostic, clinical, histopathological, and laboratory criteria makes differentiation of pyoderma gangrenosum and necrotizing fasciitis challenging. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a diagnosis of exclusion but a high index of suspicion is crucial to ensure the right diagnosis. Awareness of the existence of pyoderma gangrenosum is a prerequisite. The lack of this can lead to extensive morbidity of the patient. Finally and most importantly, our case illustrates that if surgical intervention leads to deterioration of the lesion and the microbial cultures remain negative, diagnoses other than infection should be considered and a dermatologist consulted.

In summary, pyoderma gangrenosum is a rare complication of surgery and is difficult to recognize. Usually the condition is wrongly diagnosed as a postoperative infection such as necrotizing fasciitis. Our case report illustrates some of the problems and pitfalls that can arise. Following a nerve decompressive surgery, our patient developed an expanding ulcer. This finding along with the constitutional symptoms and elevated inflammatory markers were interpreted as a case of necrotizing fasciitis. Yet blood, urine, and wound cultures were repeatedly negative. Progression was seen in spite of antibiotics and 10 surgical revisions. After a multidisciplinary consultation, the dermatologists diagnosed pyoderma gangrenosum.

- Barr K L, Chhatwal H K, Wesson S K, Bhattacharyya I, Vincek V. Pyoderma gangrenosum masquerading as necrotizing facsiitis. Am J Otolaryngol 2009; 30: 273–6.

- Bisarya K, Azzopardi S, Lye G, Drew P J. Necrotizing fasciitis versus pyoderma gangrenosum: securing the correct diagnosis! A case report and literature review. Eplasty 2011; 11: e24.

- Mahajam A L, Ajmal N, Barry J, Barnes L, Lawlor D. Could your case of necrotising fascitis be Pyoderma gangrenosum? Br J Plastic Surg 2005; 58: 409–12.

- McKee P H, Calonje C, Brenn T, Lazar A. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin (4th ed.). Elsevier Saunders 2012 pp 631–5.

- Patel F, Fitzmaurice S, Duong C, Young H E, Fergus J, Raychaudhuri S P, Shirakawa Garcia M, Maverakis E. Effective strategies for the management of pyoderma gangrenosum: A comprehensive review. Acta Derm Venereol 2015; 95: 525–31.

- Utrillas-Compaired A, Jeavons R P, Viana-López R, González-Gómez I. Necrotizing dermatosis of the arm following cubital tunnel release: Pyoderma gangrenosum, the great mimic. J Bone Joint Surg Case Connect 2015; 5: e55.

- Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen M D. Pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet syndrome: the prototypic neutrophilic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol 2015 July 22. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13955.

- Wangia M W, Mitchell C L, Wesson S K, Scott E, Glavin F L. Pyoderma gangrenosum or necrotizing fasciitis? A diagnostic conundrum. Case report and literature review. J Pediatr Surg 2013; 1: 139–42.

- Wollina U. Pyoderma gangrenosum – a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007; 2: 19.

- Wong C-H, Chang H-C, Pasupathy S, Khin L-W, Tan J-L, Low C-O. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85: 1454–60.