Abstract

Background and purpose — Total hip replacement (THR) is the preferred method for the active and lucid elderly patient with a displaced femoral neck fracture (FNF). Controversy still exists regarding the use of cemented or uncemented stems in these patients. We compared the effectiveness and safety between a modern cemented, and a modern uncemented hydroxyapatite-coated femoral stem in patients 65–79 years of age who were treated with THR for displaced FNF.

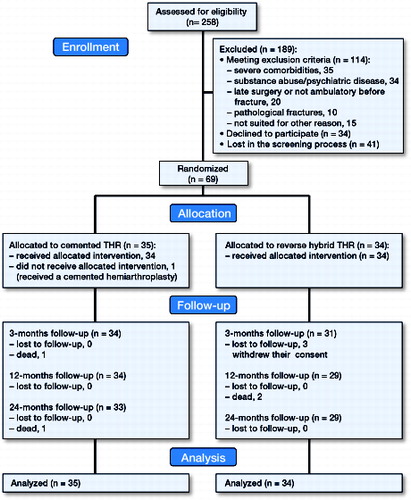

Patients and methods — In a single-center, single-blinded randomized controlled trial, we included 69 patients, mean age 75 (65–79) and with a displaced FNF (Garden III–IV). 35 patients were randomized to a cemented THR and 34 to a reverse-hybrid THR with an uncemented stem. Primary endpoints were: prevalence of all hip-related complications and health-related quality of life, evaluated with EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D) index up to 2 years after surgery. Secondary outcomes included: overall mortality, general medical complications, and hip function. The patients were followed up at 3, 12, and 24 months.

Results — According to the calculation of sample size, 140 patients would be required for the primary endpoints, but the study was stopped when only half of the sample size was included (n = 69). An interim analysis at that time showed that the total number of early hip-related complications was substantially higher in the uncemented group, 9 (among them, 3 dislocations and 4 periprosthetic fractures) as compared to 1 in the cemented group. The mortality and functional outcome scores were similar in the 2 groups.

Interpretation — We do not recommend uncemented femoral stems for the treatment of elderly patients with displaced FNFs.

Total hip replacement (THR) is the preferred method for the active and lucid elderly patient with a displaced femoral neck fracture (FNF) (Chammout et al. Citation2012). Comparisons between cemented and uncemented stems in hip arthroplasty for patients with a FNF have almost consistently favored cemented fixation, mainly because of superior outcome in pain relief, walking ability, use of walking aids, and activities of daily living (Parker et al. Citation2010)—and because of a higher incidence of complications such as periprosthetic fracture (Khan et al. Citation2002) for uncemented implants. Despite this, recent reports on modern uncemented, hydroxyapatite-coated femoral stems used for this patient group have shown promising early results (CitationFigved et al. 2009, Sköldenberg et al. Citation2011, Kim and Oh Citation2012). In addition, bone cement implantation syndrome is more prevalent in cemented stems than in uncemented stems (Parvizi et al. Citation1999), and in patients with a femoral neck fracture. Severe bone cement implantation syndrome has a substantial impact on early and late mortality (Olsen et al. Citation2014). Thus, the use of uncemented hydroxyapatite stems for this patient group may still be justified.

We hypothesized that an uncemented, proximally porous and hydroxyapatite-coated femoral stem used in THR for a displaced FNF would not be associated with more adverse perioperative and postoperative events compared to a THR using a cemented stem, and that the health-related quality of life of the patients would be equivalent at 2 years.

Patients and methods

Trial design, settings, and location

This single-center, single-blinded, randomized controlled trial (CHANCE trial) followed the guidelines of good clinical practice (ICH-GCP) and the CONSORT statement, and was performed between 2009 and 2016 (inclusion period: September 2009 through March 2014) at the orthopedic department of Danderyd Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden.

Study subjects and eligibility criteria

All patients with a displaced FNF who were admitted to Danderyd Hospital during the inclusion period were screened for participation in the study. Patients who agreed to participate gave their oral and written informed consent before inclusion. The inclusion criteria were: displaced FNF (Garden III–IV), surgery within 48 h, age 65–79 years, no concurrent joint disease or previous fracture in the lower extremities, intact cognitive function (no diagnosis of dementia and at least 7 correct answers on a 10-item Short Portable Mental Status questionnaire), and ability to ambulate independently with or without walking aids. We excluded patients with pathological fractures and those with rheumatoid arthritis or symptomatic osteoarthritis. We also excluded those who, because of severe comorbidities, were deemed unsuitable for a THR by the anesthesiologist, and those who were unsuitable for participation in the study for any other reason.

Data collection and follow-up

The primary assessment established that the patient fulfilled the inclusion/exclusion criteria and identified any comorbidity. The patients were interviewed by a research nurse regarding living conditions, mobility, activities of daily living (ADL) status, and health-related quality of life according to the EQ-5D during the last week before the fracture as a baseline. The patients were followed up at 3,12, and 24 months. Patients who were unable or unwilling to attend follow-up visits were interviewed by telephone, or they sent in their completed questionnaires. We used the Swedish unique personal ID number to identify all hip-related complications during the study period. We searched digital medical charts at Danderyd Hospital, the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register, and the Swedish Patient Registry. All hip-related complications in the study were managed and registered at our department, and no other reoperations or complications were found to have occurred at other hospitals in Sweden.

Surgery

22 surgeons (at consultant or specialist level) who were experienced in both procedures performed the operations. 1 surgeon operated 16 patients, another operated 8 patients, and the others operated between 1 and 4 patients each. A direct lateral approach with the patient in the lateral decubitus position was used. Preoperative surgical planning was performed using digital software (MDesk; RSA Biomedical AB, Umeå, Sweden). The modular CPT (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN) was used in the cemented group. The Bi-Metric stem (Biomet, Warsaw, IN) was used in the uncemented group. A 32-mm cobalt-chromium head was used in all patients.

The acetabular component used in the patients was a cemented cup, except in 3 patients who received an uncemented cup according to the surgeon’s preference.

In the cemented group, the proximal femur was reamed with 1 or 2 reams and was then prepared with broaches of increasing size. The cement bed was cleaned with repeated high-pressure pulsatile lavage. A distal restrictor was used when cementing the femoral component. In the uncemented group, the femur was reamed until cortical bone contact was obtained. Then the proximal femur was prepared with broaches of increasing size until rotational stability was achieved.

All patients were given low-molecular-weight heparin postoperatively for at least 10 days. Antibiotic prophylaxis with cloxacillin (2 g) was given preoperatively, followed by 3 additional doses during the first 24 h. The patients were mobilized without any restrictions.

Primary endpoints

The primary endpoints were (1) the prevalence of all hip-related complications and reoperations, and (2) change in health-related quality of life assessed with EQ-5D index (EuroQol). Hip-related complications were defined as intraoperative and postoperative periprosthetic fracture, dislocations, wound infection (both superficial and deep), early and late loosening, and reoperation of the hip for any reason. The endpoints were measured at 24 months after surgery.

Secondary endpoints

The secondary endpoints included overall mortality and hip function at 3, 12, and 24 months evaluated with Harris hip score (HHS). Other endpoints included pain in the involved hip (measured with a visual analog scale (VAS)), and ability to carry out ADL. Other data collected included intraoperative bleeding, duration of surgery, and intraoperative vital signs (blood pressure, pulse oximetry prior to and during stem insertion) to estimate any decrease in value during cementing as signs of bone cement implantation syndrome (Donaldson et al. Citation2009). In addition, we measured serological markers of inflammation (C-reactive protein (CRP)) and thrombosis (D-dimer) preoperatively, on postoperative day (POD) 1, on POD 4, and at 3 months.

We recorded all general medical complications including cardiovascular events, acute heart infarct, cerebral vascular lesions, pulmonary embolism, and deep-vein thrombosis.

Radiology

An anteroposterior (AP) view of the pelvis and AP and lateral views of the hip were taken pre- and postoperatively, and also at 24 months, and these were reviewed by an independent radiologist (EL). All femurs were classified preoperatively as type A, B, or C according to the Dorr classification (Dorr et al. (Citation1993). Postoperative heterotopic ossification at 24 months was graded as described by Brooker et al. (Citation1973).

Sample size and power analysis

To show non-inferiority with 80% power of the primary endpoint, all hip-related complications between the 2 groups, assuming a total complication rate of 20%, would require 60 patients in each group with a non-inferiority limit of 15%. Showing non-inferiority with 80% power of the primary variable health-related quality of life (HRQoL)—measured with EQ-5D—would require 40 patients in each group, assuming a value of 0.73 (SD 0.18) and a non-inferiority limit of 0.1. Both calculations were done with p < 0.025 instead of p < 0.05 to handle multiplicity. Since this patient group has a 1-year mortality of 10%, 70 patients in each group (140 total) would be sufficient for the study.

Interim analyses and stopping guidelines

We were aware of the risk of periprosthetic fracture using uncemented stems in elderly patients with FNF, so before the start of the study—and as a safety briefing—we planned to perform an interim analysis of the primary endpoints when we had included half of the sample size. If we found a disproportionate number of hip-related complications or other complications in the uncemented group, we would stop the study.

Randomization and blinding

The patients were block-randomized in groups of 10 in a 1:1 ratio, to receive either a cemented or an uncemented stem. We used sealed envelopes and randomization was stratified by sex to ensure that the sex distribution would be the same in both groups. The participants, who were the primary outcome assessors, were blinded as to the choice of treatment. To verify that the blinding was maintained during the study, the patients were asked if they knew their assigned treatment at the 1-year follow-up. The surgeons and staff were not blinded during the study.

Statistics

Analyses of outcome were based on the intention-to-treat principle and all the patients remained in their randomized group regardless of any further surgical intervention. Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) were used to describe the patient characteristics and outcome variables at the measurement points. Fisher’s exact test was used to test the first primary endpoint. We used Student’s t-test and Levene’s test for comparison of the second primary endpoint and also other functional outcomes, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. For the 3 subjects in the uncemented group who withdrew from the study before completion, the data from the last observation was carried forward (imputed). Any p-values ≤0.05 were considered significant. We used SPSS version 22 for all analyses.

Ethics and registration

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the ethics committee of Karolinska Institute (2009/97-31/2). The study was also registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (identifier: NCT02247791) and the study protocol has been published (Chammout et al. Citation2016).

Results

Patient flow and baseline data

Between September 2009 and March 2014, 258 patients with displaced FNF were admitted to the orthopedic department of Danderyd Hospital. Of these, 69 patients met the inclusion criteria and were recruited to participate in the study (). The mean age was 73 years and 47 patients were female. There were twice as many patients with ASA 3–4 in the uncemented group (). All subjects received their allocated treatment except 1 patient in the cemented group, who received a cemented hemiarthroplasty (HA) instead of a THR. Regarding hip complications and reoperations, we could follow up all patients including the 3 patients who refused to come for clinical follow-up visits. The principal investigator (OS) stopped the inclusion when only half of the sample size had been reached (n = 69). The interim analysis at that time showed that the incidence of hip complications was statistically significantly higher in the uncemented group.

Table 1. Baseline data for all patients included in the study (n = 69)

Operative data

The mean surgery time was 13 min shorter in the uncemented group. The decrease in blood pressure during stem insertion did not (for any individual patient) reach the level that occurs in bone cement implantation syndrome grade 1 (Donaldson et al. Citation2009). Pulse oximetry decreased below 94% in 1 patient in each group, reaching the level in bone cement implantation syndrome grade 1. No deaths or cardiovascular collapse occurred during the cementing procedure. The operative data are presented in .

Table 2. Operative data. Values are mean (SD)

Primary endpoints

Up to 2 years after surgery, 8 patients suffered at least 1 hip-related complication, 1 in the cemented group and 7 in the uncemented group (relative risk =7, 95% CI: 1–55; p = 0.03, Fisher’s exact test) (). 4 patients in the uncemented group underwent a major reoperation, as compared to 0 in the cemented group. The health-related quality of life EQ-5D was similar and there was no statistically significant or clinically significant difference between the groups during the study period (Table 4, see Supplementary data). The only complication that occurred in the cemented group was a dislocation of the prosthesis, which was treated with closed reduction. In the uncemented group, 3 intraoperative periprosthetic fractures occurred; 2 fractures were treated with cerclage wires and the third was treated with a plate and screws. All fractures healed, but 1 stem had excessive migration and the patient continued to have pain. The stem was later revised to a cemented stem. 1 additional periprosthetic fracture (18 months postoperatively) was fixed with cerclage wires and the stem was revised to a long uncemented stem. In the uncemented group 3 patients sustained dislocations of the prosthesis. 1 dislocation occurred after a fall, and the second was found to be dislocated on the first postoperative radiograph in a patient with an intraoperative periprosthetic fracture fixed with a plate and screws. This dislocation was treated with a change of the liner to an elevated rim. The third dislocation was due to an undersized stem, which subsided and dislocated. This stem was revised to a cemented stem. 1 patient had a superficial infection, which was treated with antibiotics.

Table 3. Complications

Secondary endpoints

Mortality – 4 patients died during the study, 2 in each group. No deaths occurred during the operation or within the first month postoperatively. There was no statistically or clinically relevant difference between the groups regarding HHS and ADL throughout the study period. The mean pain numerical rating scale (PNRS) was higher in the uncemented group during the first 3 months, while at 12 and 24 months it was higher in the cemented group. None of the differences were statistically significant (Table 4, see Supplementary data).

General complications – 4 thrombotic events occurred in the cemented group during the study period: 2 patients suffered pulmonary embolisms during the primary hospital admission and 1 patient had pulmonary embolism between the 12-month and 24-month follow-ups. All pulmonary embolisms were temporary and were treated with warfarin for 6 months. All 3 patients attended the 2-year follow-up visit. We found 1 deep-vein thrombosis at the 3-month follow-up. No thrombotic events were found in the uncemented group (mean difference =0.15, 95% CI: −0.004 to 0.31; p = 0.06). At the 3-month follow-up, 2 patients in each group had suffered heart failure. 1 patient in each group had a cerebral vascular lesion prior to the 24-month follow- up. 1 patient in the uncemented group suffered an acute myocardial infarction before the 24-month follow-up. CRP and D-dimer results were similar in both groups (Table 5, see Supplementary data). Most patients in the study had some degree of heterotopic ossification. Table 6 (see Supplementary data) shows radiological outcome.

Discussion

In this randomized clinical trial on healthy elderly patients with a displaced femoral neck fracture treated with THR, we found a higher rate of hip-related complications in the uncemented group than in the cemented group. In addition, no advantage in using uncemented stems was found for the other endpoints.

The strengths of this study were its blind, randomized controlled design. Unlike previous trials, which compared cemented and uncemented hemiarthroplasty (CitationFigved et al. 2009, Moroni et al. Citation2009, Deangelis et al. Citation2012, Taylor et al. Citation2012, Talsnes et al. Citation2013), our study compared cemented THR with reverse-hybrid THR for displaced FNF using modern cemented and uncemented hydroxyapatite-coated stems. Other strengths were the use of intention-to-treat analysis and the randomization process being stratified by sex to ensure equal sex distribution.

The main limitation was the small number of patients because the study was stopped prematurely due to the high rate of complications in the uncemented group, so only half of the intended sample size could be included. We did not stratify according to ASA classification and the type of femur according to Dorr et al. (Citation1993), which were also limitations of the study. This introduced bias, leading to more patients with ASA 3–4 and with femur Dorr type B in the uncemented group. These differences may also have affected the results. Our trial did not have the statistical power to address the possible adverse effects of cement, and we did not find any indications of differences between the groups related to cementing, regarding mortality. All the thrombotic events occurred in the cemented group. However, the incidence of serious cement-related complications has been reported to be low (Parvizi et al. Citation1999, Olsen et al. Citation2014) and a trial examining this would require several thousand patients. Despite this, there have been reports that perioperative cardiovascular disturbances are more frequent in elderly patients with hip fracture when cemented stems are used rather than uncemented (Yli-Kyyny et al. Citation2013).

Previous comparisons in the treatment of femoral neck fractures have almost consistently favored cemented fixation, mainly because of better mobility, lower rates of periprosthetic fractures and revision, and less thigh pain, without increasing postoperative complications (Khan et al. Citation2002, Parker et al. Citation2010). Such results are based on studies comparing non-modular old-generation prostheses, such as Austin Moore and Thompson hip implants. The use of uncemented stems for THR is popular. Good or even better results in younger patients with osteoarthritis have been achieved.(Eskelinen et al. Citation2005, Sköldenberg et al. Citation2006). However, the concept of inserting an uncemented femoral component in elderly patients also is attractive to many surgeons (Keisu et al. Citation2001), since the cementing process can induce cardiac arrhythmia and cardiorespiratory collapse, and may be associated with increased mortality compared to arthroplasty using an uncemented implant (Parvizi et al. Citation1999, Citation2004).

The rationale for using uncemented stems for displaced fractures of the femoral neck in osteoporotic elderly patients, often with a stove-pipe femur, is mainly theoretical. The potential advantage of using an uncemented femoral component is also related to the shorter duration of surgery, thereby reducing intraoperative bleeding and the risk of infection. However, an uncemented implant may be associated with design-specific complications such as stress shielding of the proximal femur, thigh pain, and a higher risk of periprosthetic fracture. In Sweden, cemented stems have primarily been used for patients with an FNF. With the introduction of modern hydroxyapatite-coated implants, uncemented fixation has increased in popularity.

The results of a previous pilot study at our clinic—on a modern hydroxyapatite-coated uncemented stem—indicated that the stem could be used for elderly patients with osteoporotic fractures of the femoral neck without increasing complications (Sköldenberg et al. Citation2011). We therefore found it justified to continue with this study. In addition to our pilot study, there was only a 12-month result from a randomized trial by CitationFigved et al. (2009) comparing hemiarthroplasty using a modern modular cemented implant with an uncemented hydroxyapatite-coated implant for treatment of FNF. The authors found no difference between the groups in HHS or EQ-5D index at 4 and 12 months. This result is similar to our findings. However, they did not find any difference in the rate of hip-related complications and in the reoperation rate. Results similar to ours regarding intraoperative periprosthetic fractures were reported in an RCT with a 2-year follow-up by Taylor et al. (Citation2012). Their results were consistent with our findings, and highlight the risk associated with introducing a press-fit stem into osteoporotic bone. In contrast to our results, in a 12-month follow-up of an RCT of 130 patients with displaced FNF who were treated with an HA, DeAngelis et al. (Citation2012) reported no difference in stem-specific complications.

A systematic review of relevant RCTs by Azegami et al. (Citation2011) concluded that cemented implants were superior regarding mobility scores and pain relief. However, this review included only 1 study that involved a modern hydroxyapatite-coated stem (CitationFigved et al. 2009).

A meta-analysis conducted by Ning et al. (Citation2014) found similar rates of hip-related complications and residual pain between those treated with cemented or uncemented HA. Their analysis included 12 studies, but only 4 (CitationFigved et al. 2009, Moroni et al. Citation2009, Deangelis et al. Citation2012, Talsnes et al. Citation2013) compared modern hydroxyapatite-coated uncemented HA with cemented HA. Similar results to ours regarding hip-related complications and functional outcome with the Bi-Metric stem were reported by Inngul et al. (Citation2015). For the late periprosthetic fractures, there is evidence from Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register (Leonardsson et al. Citation2012, Rogmark et al. Citation2014), from a 5-year follow-up of an RCT (Langslet et al. Citation2014), and from a pilot study (Sköldenberg et al. Citation2014) that uncemented stems constitute a risk factor for such complications in the long term. The differences in the results of these diverse studies regarding intraoperative and early postoperative hip complications may be dependant on implant-specific designs and the type of surgical approach. The use of a fully hydroxyapatite-coated stem in combination with the posterior approach appears to give good early results (CitationFigved et al. 2009, Sköldenberg et al. Citation2011, Deangelis et al. Citation2012) regarding periprosthetic fracture. Deangelis et al. used both direct anterior and posterior approaches. The studies that have shown high intraoperative and early postoperative complications have used a direct anterior approach in combination with proximally hydroxyapatite-coated stems (Inngul et al. Citation2015) or grit-blasted stems (Taylor et al. Citation2012).

We hypothesize that the direct anterior approach, in combination with a proximally thick stem may increase the risk of intraoperative fracture. One explanation may be that it is difficult to reach the posterior calcar with the rasp when using a direct anterior approach, and during impaction, this leads to loading of the anterior calcar with the anterior aspect of the rasp. The top of the rasp loads (simultaneously) the posterior cortex of the femur diaphysis, and because the posterior cortex of the femoral diaphysis is stronger than the calcar, the fracture occurs in the calcar.

In summary, in this single-blinded, randomized controlled trial on elderly patients with displaced femoral neck fractures we found a higher risk of periprosthetic fractures and reoperations with use of a reverse-hybrid THR than with use of a cemented THR. Based on our results and those of others, we do not recommend the use of uncemented stems for the treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients.

Supplementary data

Tables 4–6 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2016.1262687.

GC and OS initiated the study, followed patients, and wrote the manuscript. OM, HB, and AS also wrote the manuscript. EL analyzed the radiographs. PKP and HS followed up the patients.

No competing interests declared.

IORT_A_1262687_supplemetal.pdf

Download PDF (21.7 KB)- Azegami S, Gurusamy K S, Parker M J. Cemented versus uncemented hemiarthroplasty for hip fractures: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Hip Int 2011; 21(5): 509–17.

- Brooker A F, Bowerman J W, Robinson R A, Riley L H Jr. Ectopic ossification following total hip replacement. Incidence and a method of classification. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1973; 55(8): 1629–32.

- Chammout G K, Mukka S S, Carlsson T, Neander G F, Stark A W, Skoldenberg O G. Total hip replacement versus open reduction and internal fixation of displaced femoral neck fractures: a randomized long-term follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94(21): 1921–8.

- Chammout G, Muren O, Bodén H, Salemyr M, Sköldenberg O. Cemented compared to uncemented femoral stems in total hip replacement for displaced femoral neck fractures in the elderly: study protocol for a single-blinded, randomized controlled trial (CHANCE-trial). BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016; 17(1): 398.

- Deangelis J P, Ademi A, Staff I, Lewis C G. Cemented versus uncemented hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures: a prospective randomized trial with early follow-up. J Orthop Trauma 2012; 26(3): 135–40.

- Donaldson A J, Thomson H E, Harper N J, Kenny N W. Bone cement implantation syndrome. Br J Anaesth 2009; 102 (1): 12–22.

- Dorr L D, Faugere M C, Mackel A M, Gruen T A, Bognar B, Malluche H H. Structural and cellular assessment of bone quality of proximal femur. Bone 1993; 14 (3): 231–42.

- Eskelinen A, Remes V, Helenius I, Pulkkinen P, Nevalainen J, Paavolainen P. Total hip arthroplasty for primary osteoarthrosis in younger patients in the Finnish arthroplasty register. 4,661 primary replacements followed for 0-22 years. Acta Orthop 2005; 76(1): 28–41.

- Figved W, Opland V, Frihagen F, Jervidalo T, Madsen JE, Nordsletten L. Cemented versus uncemented hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467(9): 2426–35.

- Inngul C, Blomfeldt R, Ponzer S, Enocson A. Cemented versus uncemented arthroplasty in patients with a displaced fracture of the femoral neck: a randomised controlled trial. Bone Joint J 2015; 97-B(11): 1475–80.

- Keisu K S, Orozco F, Sharkey P F, Hozack W J, Rothman R H, McGuigan F X. Primary cementless total hip arthroplasty in octogenarians. Two to eleven-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001; 83-A(3): 359–63.

- Khan R J, MacDowell A, Crossman P, Datta A, Jallali N, Arch B N, Keene G S. Cemented or uncemented hemiarthroplasty for displaced intracapsular femoral neck fractures. Int Orthop 2002; 26(4): 229–32.

- Kim Y H, Oh J H. A comparison of a conventional versus a short, anatomical metaphyseal-fitting cementless femoral stem in the treatment of patients with a fracture of the femoral neck. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012; 94(6): 774–81.

- Langslet E, Frihagen F, Opland V, Madsen J E, Nordsletten L, Figved W. Cemented versus uncemented hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures: 5-year followup of a randomized trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014; 472 (4): 1291–9.

- Leonardsson O, Kärrholm J, Åkesson K, Garellick G, Rogmark C. Higher risk of reoperation for bipolar and uncemented hemiarthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (5): 459–66.

- Moroni A, Pegreffi F, Romagnoli M, Hoang-Kim A, Tesei F, Giannini. Result in osteoporotic femoral neck fractures treated with cemented versus uncemented hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009; 91-B(SUPP I): 167.

- Ning G Z, Li Y L, Wu Q, Feng S Q, Li Y, Wu Q L. Cemented versus uncemented hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures: an updated meta-analysis. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2014; 24(1): 7–14.

- Olsen F, Kotyra M, Houltz E, Ricksten S E. Bone cement implantation syndrome in cemented hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture: incidence, risk factors, and effect on outcome. Br J Anaesth 2014; 113 (5): 800–6.

- Parker M J, Gurusamy K S, Azegami S. Arthroplasties (with and without bone cement) for proximal femoral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; (6): CD001706.

- Parvizi J, Holiday A D, Ereth M H, Lewallen D G. The Frank Stinchfield Award. Sudden death during primary hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999; (369): 39–48.

- Parvizi J, Ereth M H, Lewallen D G. Thirty-day mortality following hip arthroplasty for acute fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004; 86-A(9): 1983–8.

- Rogmark C, Fenstad A M, Leonardsson O, Engesæter L B, Kärrholm J, Furnes O, et al. Posterior approach and uncemented stems increases the risk of reoperation after hemiarthroplasties in elderly hip fracture patients: An analysis of 33,205 procedures in the Norwegian and Swedish national registries. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (1): 18–25.

- Sköldenberg O G, Bodén H S, Salemyr M O, Ahl T E, Adolphson P Y. Periprosthetic proximal bone loss after uncemented hip arthroplasty is related to stem size: DXA measurements in 138 patients followed for 2-7 years. Acta Orthop 2006; 77 (3): 386–92.

- Sköldenberg O G, Salemyr M O, Bodén H S, Lundberg A, Ahl T E, Adolphson P Y. A new uncemented hydroxyapatite-coated femoral component for the treatment of femoral neck fractures: two-year radiostereometric and bone densitometric evaluation in 50 hips. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93(5): 665–77.

- Sköldenberg O G, Sjöö H, Kelly-Pettersson P, Bodén H, Eisler T, Stark A, et al. Good stability but high periprosthetic bone mineral loss and late-occurring periprosthetic fractures with use of uncemented tapered femoral stems in patients with a femoral neck fracture: A 5-year follow-up of 31 patients using RSA and DXA. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (4): 396–402.

- Talsnes O, Hjelmstedt F, Pripp AH, Reikerås O, Dahl O E. No difference in mortality between cemented and uncemented hemiprosthesis for elderly patients with cervical hip fracture. A prospective randomized study on 334 patients over 75 years. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2013; 133(6): 805–9.

- Taylor F, Wright M, Zhu M. Hemiarthroplasty of the hip with and without cement: a randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94(7): 577–83.

- Yli-Kyyny T, Ojanperä J, Venesmaa P, Kettunen J, Miettinen H, Salo J, Kröger H. Perioperative complications after cemented or uncemented hemiarthroplasty in hip fracture patients. Scand J Surg 2013; 102(2): 124–8.