Abstract

Background and purpose — The annual number of total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) has increased worldwide in recent years. To make projections regarding future needs for primaries and revisions, additional knowledge is important. We analyzed and compared the incidences among 4 Nordic countries

Patients and methods — Using Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association (NARA) data from 4 countries, we analyzed differences between age and sex groups. We included patients over 30 years of age who were operated with TKA or unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) during the period 1997–2012. The negative binomial regression model was used to analyze changes in general trends and in sex and age groups.

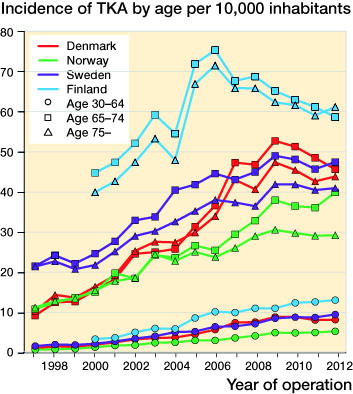

Results — The average annual increase in the incidence of TKA was statistically significant in all countries. The incidence of TKA was higher in women than in men in all 4 countries. It was highest in Finland in patients aged 65 years or more. At the end of the study period in 2012, Finland’s total incidence was double that of Norway, 1.3 times that of Sweden and 1.4 times that of Denmark. The incidence was lowest in the youngest age groups (< 65 years) in all 4 countries. The proportional increase in incidence was highest in patients who were younger than 65 years.

Interpretation — The incidence of knee arthroplasty steadily increased in the 4 countries over the study period. The differences between the countries were considerable, with the highest incidence in Finland. Patients aged 65 years or more contributed to most of the total incidence of knee arthroplasty.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for severe osteoarthritis (OA) has good long-term outcomes, and gives greater pain relief and better functional improvement than non-surgical treatment (Carr et al. Citation2012, Skou et al. Citation2015). Good long-term implant survivorship has resulted in TKA also becoming a treatment for severe knee OA in younger patients, although outcomes and implant survivorship have been reported to be worse than in elderly patients (Lonner et al. Citation2000, Rand et al. Citation2003, Price et al. Citation2010, Julin et al. Citation2010).

Reported increases in the rate of TKA and estimates of future demand predict a substantial increase in the incidence of TKA in many countries (Jain et al. Citation2005, Kurtz et al. Citation2007, Kim et al. Citation2008, Culliford et al. Citation2010, W-Dahl et al. Citation2010a, Nemes et al. Citation2015). Both the broadening of indications for younger patients and the increase in total incidence of TKA have raised concerns of a possible increase in revision burden in the long term (Kurtz et al. Citation2007, Gioe et al. Citation2007). Differences between geographic locations and age groups have been noted in the incidences of TKA (Katz et al. Citation1996, Wells et al. Citation2002). The major increase in the incidence of TKA has been found in people born in the period 1946–1964 (the baby-boomer generation) (Leskinen et al. Citation2012).

The aim of this study was to analyze trends in the incidence of TKA and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) using Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association (NARA) data from between 1997 and 2012, to identify any changes or differences in (or between) age groups, the sexes, and countries.

Patients and methods

The NARA compiles data on 4 Nordic countries that have similar organization of healthcare and comparable patient characteristics (). The NARA has information on the TKAs and UKAs performed in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden from 1997 through 2012 and in Finland from 2000 through 2012.

Table 1. Patient characteristics. Mean age applies to both TKA and UKA. The number of operations has been divided into age groups. Study period 1997–2012, except for Finland (2000–2012)

The knee arthroplasty registries of Sweden (SKAR) and Denmark (DKR) and the arthroplasty registries of Norway (NAR) and Finland (FAR) participated in the present study. All 4 registries have used individual-based registration of operations and patients. A minimal NARA dataset was created to contain data that all 4 registries could deliver, but for administrative reasons the Finnish Arthroplasty Register has been able to provide Finnish data according to the NARA data definitions from the beginning of 2000. A pilot study carried out from NARA data did not include FAR data and it did not have an age cutoff (Robertsson et al. Citation2010). The NARA database includes data on the patients that enable TKA and UKA incidence analyses, i.e. patient-level data on both demographics and implant types.

Selection and transformation of the respective datasets and de-identification of the patients, which included deletion of the national civil registration numbers, were performed within each national register. The anonymous data were then merged into a common database. Because of the small number of patients aged 30 years or less who were operated, in the present study we only included patients aged 30 years or more who had undergone a TKA or UKA surgical procedure due to primary osteoarthritis of the knee.

The data were treated with full confidentiality, according to the regulations of the respective countries. This included restricted access to the common database, which was limited to the authors of the present paper. The quality of data in the Nordic registries is high, and the registries have both national coverage and a high degree of completeness (annual reports 2015: Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register, Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register, Finnish Arthroplasty Register) (Arthursson et al. Citation2005, Espehaug et al. Citation2006).

Ethics

Ethical approval for the study was obtained through the ethical approval process of each national registry.

Statistics

We described patient characteristics, categorized into sex and age groups, using descriptive statistics presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). Incidences are presented as the number of operations performed per 104 of population. Age was categorized into 3 groups: < 65 years, 65–74 years and ≥75 years. We analyzed trends in the general incidence of TKAs and UKAs in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden from 1997 to 2012 and in Finland from 2000 to 2012. The incidence was calculated as incidence density, which is defined as the number of new cases in a population during a given time period relative to the sum of the person-time values of the at-risk population. Negative binomial regression was used to estimate the incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of UKAs and TKAs for each country because of evidence of overdispersion of data. IRR reports the estimated average annual increase of incidence. Analyses were stratified by sex and age group. The statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 22.0 and Stata 8.2 software.

Results

Patient characteristics

385,310 primary knee arthroplasties were registered in the 4 countries during the study period. During this period, we observed an increase in OA from 84% to 90% and simultaneously a decline in rheumatoid arthritis from 10% to 4% as indication for knee arthroplasty. Of these operations, 317,008 TKAs and 27,687 UKAs were performed for knee OA in patients aged 30 years or more. Female patients represented 202,940 (64%) of the TKA cases and 15,778 (57%) of the UKA cases. The mean age of the patients was 70 years (SD 9.0) in the TKA group and 65 years (SD 9.4) in the UKA group ().

Incidence of knee arthroplasty (TKA and UKA)

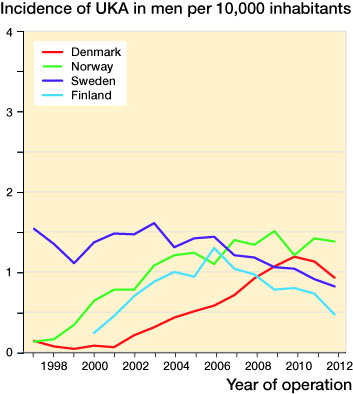

In all 4 countries, the incidences of knee arthroplasty increased during the study period (). At the beginning of the study, the incidences were 3.4 in Denmark, 3.6 in Norway, 9.0 in Sweden, and 13 in Finland per 10,000 population. At the end of the study, the incidences were 21 in Denmark, 14 in Norway, 21 in Sweden, and 28 in Finland per 10,000 population. The relative change in incidence of knee arthroplasty was 6.0-fold in Denmark, 3.9-fold in Norway, 2.3-fold in Sweden, and 2.1-fold in Finland from the start of the study to the end.

Figure 1. Total incidence of TKA and UKA by year of operation in patients aged 30 years or more. Incidences are shown per 10,000 inhabitants. The incidence in Denmark is estimated to include 10–15% underestimation between 1997 and 2007 due to lower completeness.

The relative change in incidence of UKA was 10-fold in Denmark, 1.5-fold in Finland, 7.1-fold in Norway, and 0.5-fold in Sweden from the start of the study to the end.

During the study period, the estimated average annual increase in the incidence of TKA by age groups and sex was statistically significant in all countries, with the exception of Finnish females aged 65–74 years (IRR =1.02, 95% CI: 1.00–1.03) (). IRR was highest in the youngest age group in both sexes and a decreasing trend was detected as age increased. Females had lower IRRs, except in Denmark in patients aged 65–74 years. A statistically significant decrease in UKAs was detected in Sweden in patients who were 65 years or more, whereas in Denmark and in Norway there was a significantly higher annual incidence of UKA in all age groups—except for UKAs in women aged 75 years or more in Norway. There was no significant change in the annual incidence of UKA over the study period in Finland, in men or women of any age group ().

Table 2. Negative binomial regression analysis. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) with 95% confidence intervals

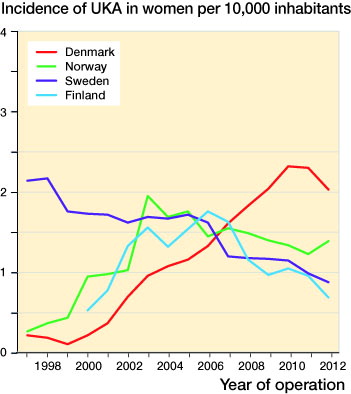

Incidence by sex

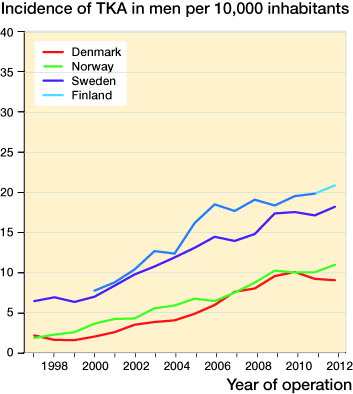

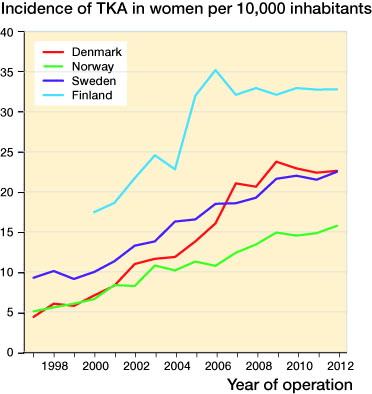

The incidences of TKA according to sex are shown in and . The incidence was higher in women than in men in all 4 countries. At the end of the study period, the incidences of TKA were 9.1 in Denmark, 11.0 in Norway, 18.2 in Sweden, and 20.9 in Finland per 10,000 men—giving a relative change of 4.2-fold in Denmark, 5.9-fold in Norway, 2.8-fold in Sweden, and 2.7-fold in Finland from the start of the study to the end. In women, the incidences of TKA were 22.6 in Denmark, 15.7 in Norway, 22.5 in Sweden, and 32.8 in Finland per 10,000 women at the end of the study, and the relative change was 5.2-fold in Denmark, 3.1-fold in Norway, 2.4-fold in Sweden, and 1.9-fold in Finland from the start of the study to the end.

Figure 2. Incidence of TKA in males aged 30 years or more. Incidences are shown per 10,000 inhabitants.

Figure 3. Incidence of TKA in females aged 30 years or more. Incidences are shown per 10,000 inhabitants.

The incidence of UKA was higher in Sweden in both men and women at the start of the study than at the end of the study, whereas in the other 3 countries the incidence of UKA was higher at the end of the study than at the start of the study ( and ).

Incidence by age group

The incidence of TKA was highest in Finland in patients aged 65 years or more. The total incidence was lowest in the youngest age group in all countries. The incidence was higher at the start of the study than at the end in all age groups ().

Discussion

We found that the total incidence, comprising both TKAs and UKAs, increased in all countries and the trends of increase were comparable between countries. The increase in surgical procedures in Finland from 2004 to 2006 may be explained by the coming into force of a new social and healthcare regulation that instructed hospitals to shorten patient waiting times for surgery. Despite having comparable socioeconomic situations and healthcare systems, differences in the incidence of knee arthroplasty between countries were notable. A pilot study from the NARA data tested a common dataset and reported results from the period 1997–2007 (Robertsson et al. Citation2010). The present study continued to analyze changes in the incidence of arthroplasty until 2012, based on experience gained from the pilot study.

The total increase in the number of arthroplasties in all countries was mainly caused by an increased incidence of TKA. In Sweden, there was a significant decrease in the incidence of UKA in patients aged 65 years or more. In 3 other countries, variations in incidences of UKA between groups were more heterogeneous (, and ). The reasons for the changes in incidence of UKA are multifactorial. Previous studies from national registries have affected UKA incidences, as most registries show higher overall revision rates of UKAs than of TKAs (Furnes et al. Citation2007, Koskinen et al. Citation2008, W-Dahl et al. Citation2010b). However, there have also been studies claiming better clinical outcome from UKA and also more cost-effectiveness (Slover et al. Citation2006, Lygre et al. Citation2010). Different UKA implant models with a longer learning curve compared to TKA, indications for primary UKA surgery, and a higher revision risk than with TKA may explain the differences in the incidence compared to TKA. The increase in the incidence of UKA in patients less than 65 years of age may be explained by the increase in minimally invasive surgery (MIS), which enables a shorter postoperative stay in hospital.

The 4 countries had comparable populations with regard to age and sex, and therefore instead of age-standardized data we analyzed incidence between age groups. Of the 3 age groups, patients less than 65 years of age had the lowest incidence of TKA. However, the relative increase in incidence was higher in that age group than in the other age groups. In recent years, it appears that the indications have widened to include younger patients, which has resulted in a proportionally higher increase in incidence in patients less than 65 years of age, compared to patients aged 65 years or less (Robertsson et al. Citation2010, Leskinen et al. Citation2012). Before this, knee arthroplasty surgery was initially reserved for elderly patients and those with severe disease (Robertsson et al. Citation2014), and younger patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The reasons for increasing incidence in younger TKA patients may be multifactorial. Increasing obesity in young people (Kautiainen Citation2005, Lohmander et al. Citation2009), participation in contact sports (Driban et al. Citation2015), and the introduction of fast-track surgery (which suits younger patients well) are probable reasons.

The present study had some strengths and limitations. The major strength was the unique collaboration of 4 national registries in the creation of a multinational database covering a large number of patients, which enabled international comparisons to reveal possible differences and which might help to estimate future demands. Furthermore, the completeness and validity of data were high in the Nordic countries at the end of the study period (completeness, NAR: 95%; SKAR: 97%; DKR: 97%; FAR: 96%) (annual reports 2015: Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register, Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register, Finnish Arthroplasty Register). Completeness in the DKR was reported to be 89% in 2007 (Robertsson et al. Citation2010), which may have caused 10–15% underestimation of incidence in Denmark over the period 1997–2007. Total relative change in incidence was highest in Denmark, and that may have been due to the influence of a lower completeness for the DKR in the early years of the study period (Table 3). The lack of data on BMI and other subgroups could also be considered a limitation of the present study.

The incidence of TKA steadily increased in all participating countries in this study, which is in line with findings from other studies (Kurtz et al. Citation2007, W-Dahl et al. Citation2010a, Leskinen et al. Citation2012). The incidence of knee arthroplasty in females was found to be greater than that in males in our study, but the results of previous studies have also shown that the proportion of female patients has decreased with time (Nemes et al. Citation2015). Moreover, the sex distribution may also vary between nations (Paxton et al. Citation2011, Nemes et al. Citation2015). One study delivered projections for primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030 (Kurtz et al. Citation2007). In that study, the authors predicted that if the number of total knee arthroplasties performed continues at the current rate, the demand for primary TKA would be projected to grow by a factor of 7 by 2030. In another previous study from the Finnish Arthroplasty Registry, the annual cumulative incidence of UKA and TKA increased rapidly between 1980 and 2006, especially in patients aged 50–59 years, the so-called baby-boomer generation (Leskinen et al. Citation2012). In our study, the increase in incidence was mainly due to the increase in incidence of TKAs. This finding is consistent with a study by W-Dahl et al. (Citation2010a) from the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register, which showed that although the incidence of TKA has increased in patients under 55 years of age, the incidence of UKA and high tibial osteotomy (HTO) has decreased. Obesity is also a growing burden in many countries and, as this has been shown to be a certain risk factor for knee osteoarthritis, especially in young patients, it may contribute to the increasing demand for TKAs in future (Apold et al. Citation2014a, Citationb, Silverwood et al. Citation2015).

A previous study has raised concerns about the long-term outcome of TKAs and the possibility of an increasing revision burden, because younger age has been associated with a higher risk of early periprosthetic joint infection and aseptic mechanical failure after TKA (Meehan et al. Citation2014). In another study, young age was found to impair the prognosis of TKA and was associated with increased revision rates for non-infectious reasons (Julin et al. Citation2010). A comparison study undertaken by the Norwegian Knee Arthroplasty Register and a United States arthroplasty registry showed an increased risk of revision in patients less than 65 years of age compared to patients aged 65 years or older (Paxton et al. Citation2011). In our study, the proportional growth of TKAs during the study period was highest in patients who were younger than 65 years. Despite this, the incidence of knee arthroplasty in the youngest age group was lower than in patients aged 65 years or more. Based on this finding, the majority of knee arthroplasties will probably be performed on elderly patients in the future also. Even though patients less than 65 years old represented a lower incidence level than patients who were 65 or older in our study, these working-age patients should be considered to be an important subgroup because of their higher physical activity and higher demands for surgery, and the multifactorial reasons behind the success of TKA (Keeney et al. Citation2014, Klit et al. Citation2014, Parvizi et al. Citation2014). An effect on the revision burden can therefore be anticipated in future.

In summary, the incidence of knee arthroplasty has steadily increased in the 4 Nordic countries. This increase was caused by an increase in the incidence of TKA, whereas the incidence of UKA varied between countries. The proportional increase in incidence was highest in patients aged less than 65 years. However, patients who are 65 years or more still comprise the majority of those who undergo knee arthroplasty, and they are the main contributory factor to the increase in the total number of TKA operations.

Study design: MN and AE. Analysis of data and statistics: HH and MN. Review and interpretation of the results: MN, HH, and AE. Revision and approval of the final manuscript: MN, KM, OR, AW-D, OF, AF, AP, HS, and AE.

This study was funded by a NordForsk grant.

No competing interest declared.

- Apold H, Meyer H E, Nordsletten L, Furnes O, Baste V, Flugsrud G B. Risk factors for knee replacement due to primary osteoarthritis, a population based, prospective cohort study of 315,495 individuals. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014a; 15: 217.

- Apold H, Meyer H E, Nordsletten L, Furnes O, Baste V, Flugsrud G B. Weight gain and the risk of knee replacement due to primary osteoarthritis: A population based, prospective cohort study of 225,908 individuals. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014b; 22 (5): 652–8.

- Arthursson A J, Furnes O, Espehaug B, Havelin L I, Soreide J A. Validation of data in the norwegian arthroplasty register and the norwegian patient register: 5,134 primary total hip arthroplasties and revisions operated at a single hospital between 1987 and 2003. Acta Orthop 2005; 76 (6): 823–8.

- Carr A J, Robertsson O, Graves S, Price A J, Arden N K, Judge A, Beard D J. Knee replacement. Lancet 2012; 379 (9823): 1331–40.

- Culliford D J, Maskell J, Beard D J, Murray D W, Price A J, Arden N K. Temporal trends in hip and knee replacement in the united kingdom: 1991 to 2006. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92 (1): 130–5.

- Driban J B, Hootman J M, Sitler M R, Harris K, Cattano N M. Is participation in certain sports associated with knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review. J Athl Train 2015; [Epub ahead of print].

- Espehaug B, Furnes O, Havelin L I, Engesaeter L B, Vollset S E, Kindseth O. Registration completeness in the norwegian arthroplasty register. Acta Orthop 2006; 77 (1): 49–56.

- Furnes O, Espehaug B, Lie S A, Vollset S E, Engesaeter L B, Havelin L I. Failure mechanisms after unicompartmental and tricompartmental primary knee replacement with cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89 (3): 519–25.

- Gioe T J, Novak C, Sinner P, Ma W, Mehle S. Knee arthroplasty in the young patient: Survival in a community registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007; 464: 83–7.

- Jain N B, Higgins L D, Ozumba D, Guller U, Cronin M, Pietrobon R, Katz J N. Trends in epidemiology of knee arthroplasty in the United States, 1990-2000. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52 (12): 3928–33.

- Julin J, Jamsen E, Puolakka T, Konttinen Y T, Moilanen T. Younger age increases the risk of early prosthesis failure following primary total knee replacement for osteoarthritis. A follow-up study of 32,019 total knee replacements in the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (4): 413–9.

- Katz B P, Freund D A, Heck D A, Dittus R S, Paul J E, Wright J, Coyte P, Holleman E, Hawker G. Demographic variation in the rate of knee replacement: A multi-year analysis. Health Serv Res 1996; 31 (2): 125–40.

- Kautiainen S. Trends in adolescent overweight and obesity in the Nordic countries. Scandinavian Journal of Nutrition 2005; 49 (1): 4–14.

- Keeney J A, Nunley R M, Wright R W, Barrack R L, Clohisy J C. Are younger patients undergoing TKAs appropriately characterized as active? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472 (4): 1210–6.

- Kim H A, Kim S, Seo Y I, Choi H J, Seong S C, Song Y W, Hunter D, Zhang Y. The epidemiology of total knee replacement in south korea: National registry data. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008; 47 (1): 88–91.

- Klit J, Jacobsen S, Rosenlund S, Sonne-Holm S, Troelsen A. Total knee arthroplasty in younger patients evaluated by alternative outcome measures. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29 (5): 912–7.

- Koskinen E, Eskelinen A, Paavolainen P, Pulkkinen P, Remes V. Comparison of survival and cost-effectiveness between unicondylar arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty in patients with primary osteoarthritis: A follow-up study of 50,493 knee replacements from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2008; 79 (4): 499–507.

- Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the united states from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89 (4): 780–5.

- Leskinen J, Eskelinen A, Huhtala H, Paavolainen P, Remes V. The incidence of knee arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis grows rapidly among baby boomers: A population-based study in Finland. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64 (2): 423–8.

- Lohmander L S, Gerhardsson de Verdier M, Rollof J, Nilsson P M, Engstrom G. Incidence of severe knee and hip osteoarthritis in relation to different measures of body mass: A population-based prospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2009; 68 (4): 490–6.

- Lonner J H, Hershman S, Mont M, Lotke P A. Total knee arthroplasty in patients 40 years of age and younger with osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000; (380) (380): 85–90.

- Lygre S H, Espehaug B, Havelin L I, Furnes O, Vollset S E. Pain and function in patients after primary unicompartmental and total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92 (18): 2890–7.

- Meehan J P, Danielsen B, Kim S H, Jamali A A, White R H. Younger age is associated with a higher risk of early periprosthetic joint infection and aseptic mechanical failure after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96 (7): 529–35.

- Nemes S, Rolfson O, W-Dahl A, Garellick G, Sundberg M, Karrholm J, Robertsson O. Historical view and future demand for knee arthroplasty in Sweden. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (4): 426–31.

- Parvizi J, Nunley R M, Berend K R, Lombardi A V,Jr, Ruh E L, Clohisy J C, Hamilton W G, Della Valle C J, Barrack R L. High level of residual symptoms in young patients after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472 (1): 133–7.

- Paxton E W, Furnes O, Namba R S, Inacio M C, Fenstad A M, Havelin L I. Comparison of the Norwegian Knee Arthroplasty Register and a United States arthroplasty registry. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93Suppl3: 20–30.

- Price A J, Longino D, Rees J, Rout R, Pandit H, Javaid K, Arden N, Cooper C, Carr A J, Dodd C A, Murray D W, Beard D J. Are pain and function better measures of outcome than revision rates after TKR in the younger patient? Knee 2010; 17 (3): 196–9.

- Rand J A, Trousdale R T, Ilstrup D M, Harmsen W S. Factors affecting the durability of primary total knee prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85-A (2): 259–65.

- Robertsson O, Bizjajeva S, Fenstad A M, Furnes O, Lidgren L, Mehnert F, Odgaard A, Pedersen A B, Havelin L I. Knee arthroplasty in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. A pilot study from the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (1): 82–9.

- Robertsson O, Ranstam J, Sundberg M, W-Dahl A, Lidgren L. The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register: A review. Bone Joint Res 2014; 3 (7): 217–22.

- Silverwood V, Blagojevic-Bucknall M, Jinks C, Jordan J L, Protheroe J, Jordan K P. Current evidence on risk factors for knee osteoarthritis in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015; 23 (4): 507–15.

- Skou S T, Roos E M, Laursen M B, Rathleff M S, Arendt-Nielsen L, Simonsen O, Rasmussen S. A randomized, controlled trial of total knee replacement. N Engl J Med 2015; 373 (17): 1597–606.

- Slover J, Espehaug B, Havelin L I, Engesaeter L B, Furnes O, Tomek I, Tosteson A. Cost-effectiveness of unicompartmental and total knee arthroplasty in elderly low-demand patients. A markov decision analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88 (11): 2348–55.

- W-Dahl A, Robertsson O, Lidgren L. Surgery for knee osteoarthritis in younger patients. Acta Orthop 2010a; 81 (2): 161–4.

- W-Dahl A, Robertsson O, Lidgren L, Miller L, Davidson D, Graves S. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in patients aged less than 65. Acta Orthop 2010b; 81 (1): 90–4.

- Wells V M, Hearn T C, McCaul K A, Anderton S M, Wigg A E, Graves S E. Changing incidence of primary total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty 2002; 17 (3): 267–73.