Abstract

Background and purpose — There is a lack of information on any associations between the functional outcome and age and diagnosis in patients who have undergone shoulder arthroplasty. We therefore evaluated the functional outcome in “young” and “old” patients treated with either hemiarthroplasty (HA) or total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) with diverse diagnoses.

Patients and methods — The functional results of 496 primary shoulder arthroplasties were analyzed using the Constant score (age- and sex-adjusted) and subjective satisfaction. Patients ≤55 years of age at surgery were defined as “young. Diagnoses were primary osteoarthritis (n = 339), posttraumatic osteoarthritis (n = 78), cuff tear arthropathy (n = 36), avascular necrosis (n = 30), and rheumatoid arthritis (n = 13). Mean length of follow-up was 4 (2–14) years.

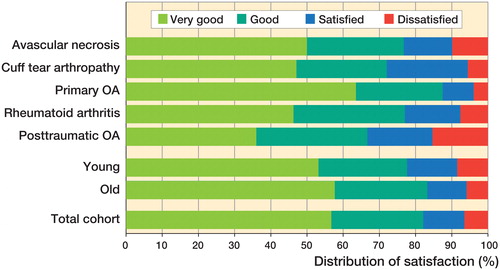

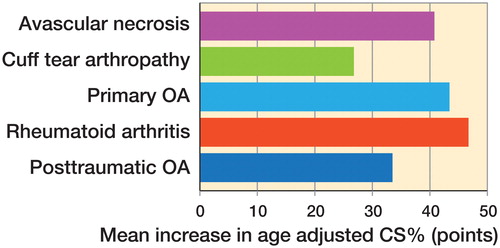

Results — 70% of the TSA patients were very satisfied with the postoperative result, as compared to 39% after HA. The Constant score and patient satisfaction were similar in the “young” and “old” groups. Pain relief was better in the “old” group. The mean improvement in the Constant score after cuff tear arthropathy (22 points) was inferior to that for primary osteoarthritis (36 points), avascular necrosis (34 points), and rheumatoid arthritis (37 points). Inferior mean Constant scores were also seen for posttraumatic osteoarthritis (29 points) compared to primary osteoarthritis (36 points). 63% of patients with primary osteoarthritis were very satisfied, as compared to only 36% of the patients with posttraumatic osteoarthritis.

Interpretation — Shoulder arthroplasty is successful in the medium term for different glenohumeral diseases, irrespective of patient age at surgery. However, the appropriate treatment method for cuff tear and posttraumatic conditions of the shoulder remains to be found, particularly in young patients.

Shoulder arthroplasty is widely used for different end-stage diseases of the glenohumeral joint (Edwards et al. Citation2003, Bryant et al. Citation2005, Deshmukh et al. Citation2005, Raiss et al. Citation2008, Kasten et al. Citation2010). In terms of functional outcome and pain relief, several studies have shown that total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) is superior to hemiarthroplasty (HA) (Gartsman et al. Citation2000, Boileau et al. Citation2002, Bryant et al. Citation2005, Lo et al. Citation2005, Pfahler et al. Citation2006, Radnay et al. Citation2007).

Predisposing factors for worse outcomes after SA are widely discussed in the literature. One of these influencing factors is age at the time of surgery. Some authors have reported worse outcomes in younger patients (Denard et al. Citation2013, Schoch et al. Citation2015). Sperling et al. (Citation1998, Citation2004) investigated patients who underwent HA or TSA and who were aged 50 years or less at the time of surgery, with a minimum follow-up of 15 years. They found unsatisfactory results in 60% of the HA group and in 50% of the TSA group, results that are worse than those reported for SA in older patients. Saltzman et al. (Citation2010) found possible risk factors for worse outcomes in younger patients, e.g. different diagnoses that led to arthroplasty, higher postoperative activity levels, higher expectations compared to older patients, and longer life expectancy.

We therefore analyzed and compared pre- and postoperative functional results in patients treated either with HA or TSA, according to age at the time of surgery and the diagnosis that led to the surgery.

Patients and methods

604 primary HAs and TSAs were performed at our institution between May 1997 and April 2009 and were included in a prospective recorded database.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) treatment with SA within the above-mentioned time period; (2) follow-up of at least 2 years; and (3) complete pre- and postoperative clinical data. Patients with fractures of the proximal part of the humerus who were treated with SA were not included. Patients regularly return to our department after 1, 2, 5, and 10 years postoperatively. Only a few patients had to be separately invited for follow-up.

Following the inclusion criteria, 108 cases from this cohort were either lost to follow-up (n = 47), died less than 2 years after the procedure (n = 18), had incomplete clinical data (n = 30), or underwent revision surgery less than 2 years postoperatively (n = 13). Of the 604 cases, 496 could be included in the study (82%).

The distributions of diagnoses were as follows: primary osteoarthritis (n = 339); (2) posttraumatic osteoarthritis (n = 78); (3) cuff tear arthropathy (n = 36); (4) avascular necrosis of the humeral head (n = 30); and (5) rheumatoid arthritis (n = 13).

TSA was performed in 282 cases (57%), while HA was performed in 214 cases (43%). Altogether, 51 patients were operated bilaterally and we separately analyzed each shoulder as this was not of any statistical disadvantage.

The cohort included 155 male patients (31%) and 341 female patients (69%). The dominant shoulder was operated in 292 cases (59%). The mean age of the patients at the time of surgery was 65 (66–90) years. They were grouped according to age at the time of surgery. Those aged less than 55 years were defined as “young” (n = 94), and those aged 55 years or older were defined as “old” (n = 402).

In all cases examined, data from the last follow-up was used for the analysis. (In cases of revision surgery, the last follow-up before revision was used). Mean length of follow-up was 52 (24–173) months.

All cases were operated directly by—or under the supervision of—the same experienced shoulder surgeon (ML).

Clinical evaluation

All patients were evaluated using the Constant-Murley score, with age- and sex-related adjustments according to Yian et al. (Citation2005). An oral question that the patient was asked to answer to the surgeon was used in order to evaluate the subjective satisfaction with the postoperative result. The question was: “How would you rate the postoperative results?” The choice of answers offered was: “very good” (1), “good” (2), “satisfied” (3), or “dissatisfied” (4).

Operative technique and implants

A deltopectoral approach was used in all cases. The surgical technique used has been described previously (Raiss et al. Citation2008).

A third-generation stemmed implant (Aequalis Total Shoulder; Tornier, Edina, MN) was used in 77 cases of HA and resurfacing arthroplasty was used in 137 cases (26 Copeland Humeral Resurfacing Heads; Biomet Orthopedics Inc., Warsaw, IN; 58 Epoca Resurfacing Heads; Synthes, Oberdorf, Switzerland; 53 Aequalis Resurfacing Heads; Tornier).

The same third-generation implant was used in all 282 cases of TSA (Aequalis Total Shoulder; Tornier). PMMA bone cement was used for implant fixation in all cases (Biomet).

Statistics

Possible differences between groups regarding continuous data were tested using the t-test or analysis of variance, depending of the number of factors in the groups. Change of difference over time within groups was tested using an I-sample t-test. Chi-square-test was used to compare categorical data between groups. Graphical methods (e.g. box plots) were used to present the findings. The level of significance was set at 0.05 (5%). Statistical analysis was done using SAS version 9.4.

Ethics and funding

The study was approved by the Ethical Board of the local university (IRB number: S-305/2007).

We thank the non-profit research foundation “Deutsche Arthrose-Hilfe e.V.”, Germany, for supporting this study.

Markus Loew has received royalties from Tornier Cie. There are no other competing interests.

Results

Compared to preoperatively, in the entire cohort there was a substantial increase postoperatively in Constant score and in age-adjusted Constant score with its subgroups shoulder flexion, abduction, internal and external rotation, and strength (496 cases; p < 0.001) (Table 1, see Supplementary data).

11 patients showed inferior functional results and had more pain at the last follow-up than preoperatively—5 of them because of secondary rotator cuff tear, and in 6 patients after HA because of secondary erosion of the glenoid bone.

The mean follow-up time was similar in the 2 age groups and also for the different diagnoses. The mean length of follow-up for HA was 45 (24–173) months and for TSA it was 57 (24–158) months (p < 0.001)

HA was preferred in younger patients without pathology of the glenoid bone and concentric glenoid wear. TSA was mainly performed on older patients suffering from primary osteoarthritis. TSA was performed on 89% of the cases who belonged to the “old” group whereas HA was performed on 66% of all cases in the “young” group.

TSA vs. HA

Results for all parameters where statistically significantly better in the TSA group than in the HA group (Table 2, see Supplementary data).

“Old” vs. “young”

Preoperative data for the “young” and “old” groups were similar in Constant score, age-adjusted Constant score with subgroups, and in shoulder flexion, abduction, internal and external rotation, and strength (Table 1, see Supplementary data).

Postoperative results showed no significant differences in Constant score (p = 0.3) and also none in age-adjusted Constant score (p = 0.07) between the 2 age groups. Patients in the “old” group had better pain relief than patients in the “young” group (p = 0.02). There were no statistically significant differences in the remaining subgroups mobility, activity, and strength, and none in shoulder flexion, abduction, and internal and external rotation (p > 0.05).

The 95% CIs for the differences between the preoperative and postoperative results for Constant score in “young” patients were lower (27–36 points) than the corresponding CIs for “old” patients (30–41 points). Therefore, “old” patients may benefit relatively more from shoulder arthroplasty. However, these differences were not statistically significant (Table 1, see Supplementary data).

Cuff tear arthropathy was strongly associated with a certain age group () whereas primary osteoarthritis, posttraumatic osteoarthritis, and avascular necrosis had a similar age distribution. The other diagnoses were too few for us to make a meaningful comparison.

Table 3. Distribution of diagnoses in the 2 age groups. Values are n

Different diagnoses

Patients with posttraumatic osteoarthritis and cuff tear arthropathy showed worse results (preoperatively to postoperatively) than those with primary osteoarthritis—both in Constant score and in age-adjusted Constant score ( and Table 4, see Supplementary data).

Figure 1. Mean postoperative increase in age-related Constant score at the time of the last follow-up, for the different diagnoses.

Preoperatively to postoperatively, we found worse results in Constant score and in age-adjusted Constant score for patients with cuff tear arthropathy than for patients with avascular necrosis and rheumatoid arthritis (p < 0.05).

Patients with the diagnosis primary osteoarthritis had better pain relief than patients with posttraumatic osteoarthritis (p < 0.001).

Subjective satisfaction

Subjective satisfaction was best for primary osteoarthritis and worst for posttraumatic osteoarthritis (). Overall, there were no significant differences between the “young” and “old” groups (p > 0.7). Patients treated with TSA had higher satisfaction rates than patients treated with HA (p < 0.001).

Complications and revisions

Intraoperative complications included a fracture of the greater tuberosity in 1 case, without further treatment. Fracture of the humeral shaft occurred in 3 cases: 1 was treated with cable wires, and open reduction and internal fixation was performed in 2 cases.

Postoperative complications included 7 cases of brachial plexus palsy. In all cases, the lesions had resolved completely 1 year postoperatively. 2 cases had superficial wound infection, which resolved with antibiotic treatment. There was 1 case of periprosthetic fracture at the humerus and 1 case of fracture of the glenoid bone; both were due to trauma that was not directly related to surgery, and both were treated conservatively.

Revision from HA to TSA was performed in 6 shoulders due to pain caused by secondary erosion of the glenoid bone (27–58 months postoperatively). In 1 case, persistent anterior subluxation of the head of the prosthesis was treated with pectoralis major transfer (27 months postoperatively). In 2 cases, revision to reverse TSA was performed due to secondary defects of the rotator cuff. Revision surgery and open reduction and internal fixation was performed in 2 cases due to perisprosthetic fractures following trauma.

Discussion

Shoulder arthroplasty is used for different diseases (Edwards et al. Citation2003, Bryant et al. Citation2005, Deshmukh et al. Citation2005, Raiss et al. Citation2008, Kasten et al. Citation2010). In terms of pain relief and functional results, TSA appears to be superior to HA (Gartsman et al. Citation2000, Boileau et al. Citation2002, Bryant et al. Citation2005, Lo et al. Citation2005, Pfahler et al. Citation2006, Radnay et al. Citation2007). This was also confirmed by the results of our study.

There is less evidence to date on the outcome in different patient populations (regarding age, diagnosis) after either HA or TSA. Particularly in patients less than 55 years of age, there is much discussion about the surgical management of degenerative changes of the glenohumeral joint. The concerns about SA in this population are mainly due to the higher demands on the operated shoulder, the higher expectations regarding the surgical result, and the longevity of the prosthetic shoulder due to increased life expectancy (Denard et al. Citation2013). Most notably, the important long-term complication of glenoid component loosening prevents many surgeons from implanting a glenoid component, even though the results are superior to those with HA and also superior to those with secondary implantation of a glenoid component (Sperling et al. Citation1998, Bryant et al. Citation2005, Radnay et al. Citation2007).

Denard et al. (Citation2013) recently published their 5- to 10-year results in a multicenter study on TSA in patients aged 55 years or younger with primary osteoarthritis. At 5 years postoperatively, they found a survival rate of 98% when revision surgery for glenoid loosening was defined as the endpoint. 10 years postoperatively, the results had become worse, with a survivorship of only 63%. Since implant failures were found exclusively on dominant shoulders, the authors assumed that increased use of the extremity might be associated with loosening of the component.

Schoch et al. (Citation2015) reported results following HA and TSA with a minimum follow-up of 20 years in patients younger than 50 years. They rated their results according to the Neer criteria and found similar results for the TSA and HA groups. It is noteworthy that most of the patients analyzed in that study were operated due to posttraumatic osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, with similar results in both. The survival rate at 20 years postoperatively was 75% for TSA and HA when revision surgery was defined as the endpoint. The authors found unsatisfactory results according to the Neer criteria in more than 60% of patients.

Sperling et al. (Citation1998, Citation2004) analyzed the post-HA and post-TSA results in patients aged 50 years or younger at the time of surgery, at 2 different follow-up dates (at least 5 years and at least 15 years). They found an increase in unsatisfactory results according to modified Neer criteria between the 2 examination dates: from 47% to 60% for HA, and similar results for TSA—with unsatisfactory results increasing from 48% to 50%. Interestingly, they found similar results in the HA and TSA groups in their survivorship analysis, even though several patients in the HA group had early revision surgery due to degenerative changes of the glenoid. It is important to mention that most of the patients analyzed in that study were operated due to posttraumatic conditions or rheumatoid arthritis. The authors concluded that the high rates of unsatisfactory results were mainly the result of soft-tissue restrictions in rheumatoid arthritis and in posttraumatic conditions.

Based on reports of worse outcomes after SA in young patients, Saltzman et al. (Citation2010) analyzed their preoperative data on 1,030 patients. They assumed that one reason might be that younger patients are treated with SA for different diagnoses, and concluded that this might have a greater influence than patient age at surgery. For example, in their cohort, 34% of the “young” patients (defined as “aged under 50”) were operated with SA due to “capsulorrhaphy arthropathy”, which they defined as “arthritis that occurs following a previous surgical stabilization procedure”.

We found similar functional outcome in relation to patient age at surgery, except that older patients had better pain relief than younger ones. Interestingly, the preoperative data showed no difference between the 2 age groups, which contrasts with the findings of Saltzman et al. (Citation2010), who assumed that younger patients might have worse preoperative function than older patients .

We found that young patients with degenerative changes of the glenohumeral joint could be successfully treated with SA, with comparable results to those in the older population. However, long-term follow-up is required in order to answer the question of whether possibly higher activity levels lead to higher complication rates, such as glenoid loosening and worse clinical outcomes.

We found that different functional results are related to the underlying diagnosis. Especially in the cuff tear arthropathy and posttraumatic osteoarthritis group, the results were inferior than in the primary osteoarthritis group. This might be explained by the altered anatomy and biomechanics, as well as soft-tissue scarring or damage in patients with cuff tear arthropathy and posttraumatic osteoarthritis. These findings appear to be in line with those in other studies (Neer Citation1970, Williams and Rockwood Citation1996, Field et al. Citation1997, Antuna et al. Citation2002, Mighell et al. Citation2003, Gronhagen et al. Citation2007, Antuna et al. Citation2008).

Saltzman et al. (Citation2010) found a higher proportion of females among the patients aged less than 50 years, which contrasts with our study. Altogether, 32% of all male patients and only 13% of all female patients were in the “young” group in our study.

The present study had several limitations. We have not presented radiographic results and, therefore, the complication rate, such as radiographic glenoid component loosening, may have been underestimated. Also, we have not separately analyzed patients who received a stemmed humeral prosthesis or a resurfacing arthroplasty. However, all of them had an anatomical design.

Some patients with worse functional results and the preoperative diagnosis of cuff tear arthropathy were treated with HA, which is in contrast to our actual treatment method. Nowadays, these patients would have been treated with reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

In summary, SA is successful in the medium term for different glenohumeral diseases, irrespective of patient age at surgery. However, the challenge remains to find the right treatment method for degenerative diseases of the shoulder, especially in young patients.

Future studies should focus on the long-term results in younger patients after HA or TSA. Especially the combination of young age and high activity levels may lead to an increase in unsatisfactory results, complications, and high revision rates in the long term.

Supplementary data

Tables 1, 2 and 4 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1280656.

BS and PR: planning of the study, data evaluation, and preparation of the manuscript. HT and MB: examination of patients and data collection. ML and FZ: examination of patients and planning of the study. TB: statistical analysis.

IORT_A_1280656_SUPP.PDF

Download PDF (25.2 KB)- Antuna S A, Sperling J W, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Cofield R H. Shoulder arthroplasty for proximal humeral nonunions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002; 11 (2): 114–21.

- Antuna S A, Sperling J W, Cofield R H. Shoulder hemiarthroplasty for acute fractures of the proximal humerus: a minimum five-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2008; 17 (2): 202–9.

- Boileau P, Avidor C, Krishnan S G, Walch G, Kempf J F, Mole D. Cemented polyethylene versus uncemented metal-backed glenoid components in total shoulder arthroplasty: a prospective, double-blind, randomized study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002; 11 (4): 351–9.

- Bryant D, Litchfield R, Sandow M, Gartsman G M, Guyatt G, Kirkley A. A comparison of pain, strength, range of motion, and functional outcomes after hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis of the shoulder. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87 (9): 1947–56.

- Denard P J, Raiss P, Sowa B, Walch G. Mid- to long-term follow-up of total shoulder arthroplasty using a keeled glenoid in young adults with primary glenohumeral arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2013; 22 (7): 894–900.

- Deshmukh A V, Koris M, Zurakowski D, Thornhill T S. Total shoulder arthroplasty: long-term survivorship, functional outcome, and quality of life. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005; 14 (5): 471–9.

- Edwards T B, Kadakia N R, Boulahia A, Kempf J F, Boileau P, Nemoz C, et al. A comparison of hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis: results of a multicenter study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2003; 12 (3): 207–13.

- Field L D, Dines D M, Zabinski S J, Warren R F. Hemiarthroplasty of the shoulder for rotator cuff arthropathy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1997; 6 (1): 18–23.

- Gartsman G M, Roddey T S, Hammerman S M. Shoulder arthroplasty with or without resurfacing of the glenoid in patients who have osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000; 82 (1): 26–34.

- Gronhagen C M, Abbaszadegan H, Revay S A, Adolphson P Y. Medium-term results after primary hemiarthroplasty for comminute proximal humerus fractures: a study of 46 patients followed up for an average of 4.4 years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007; 16 (6): 766–73.

- Kasten P, Pape G, Raiss P, Bruckner T, Rickert M, Zeifang F, et al. Mid-term survivorship analysis of a shoulder replacement with a keeled glenoid and a modern cementing technique. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92 (3): 387–92.

- Lo I K, Litchfield R B, Griffin S, Faber K, Patterson S D, Kirkley A. Quality-of-life outcome following hemiarthroplasty or total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis. A prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87 (10): 2178–85.

- Mighell M A, Kolm G P, Collinge C A, Frankle M A. Outcomes of hemiarthroplasty for fractures of the proximal humerus. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2003; 12 (6): 569–77.

- Neer C S, 2nd. Displaced proximal humeral fractures. II. Treatment of three-part and four-part displacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1970; 52 (6): 1090–103.

- Pfahler M, Jena F, Neyton L, Sirveaux F, Mole D. Hemiarthroplasty versus total shoulder prosthesis: results of cemented glenoid components. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2006; 15 (2): 154–63.

- Radnay C S, Setter K J, Chambers L, Levine W N, Bigliani L U, Ahmad C S. Total shoulder replacement compared with humeral head replacement for the treatment of primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007; 16 (4): 396–402.

- Raiss P, Aldinger P R, Kasten P, Rickert M, Loew M. Total shoulder replacement in young and middle-aged patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90 (6): 764–9.

- Saltzman M D, Mercer D M, Warme W J, Bertelsen A L, Matsen F A, 3rd. Comparison of patients undergoing primary shoulder arthroplasty before and after the age of fifty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92 (1): 42–7.

- Schoch B, Schleck C, Cofield R H, Sperling J W. Shoulder arthroplasty in patients younger than 50 years: minimum 20-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015; 24(5): 705–10.

- Sperling J W, Cofield R H, Rowland C M. Neer hemiarthroplasty and Neer total shoulder arthroplasty in patients fifty years old or less. Long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998; 80 (4): 464–73.

- Sperling J W, Cofield R H, Rowland C M. Minimum fifteen-year follow-up of Neer hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty in patients aged fifty years or younger. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2004; 13 (6): 604–13.

- Williams G R, Jr., Rockwood C A, Jr. Hemiarthroplasty in rotator cuff-deficient shoulders. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1996; 5 (5): 362–7.

- Yian E H, Ramappa A J, Arneberg O, Gerber C. The Constant score in normal shoulders. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005; 14 (2): 128–33.