Abstract

Background and purpose — Although the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis (OA) is not well understood, chondrocyte-mediated inflammatory responses (triggered by the activation of innate immune receptors by damage-associated molecules) are thought to be involved. We examined the relationship between Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and OA in cartilage from 2 joints differing in size and mechanical loading: the first carpometacarpal (CMC-I) and the knee.

Patients and methods — Samples of human cartilage obtained from OA CMC-I and knee joints were immunostained for TLRs (1–9) and analyzed using histomorphometry and principal component analysis (PCA). mRNA expression levels were analyzed with RT-PCR. Collected synovial fluid (SF) samples were screened for the presence of soluble forms of TLR2 and TLR4 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Results — In contrast to knee OA, TLR expression in CMC-I OA did not show grade-dependent overall profile changes, but PCA revealed that TLR expression profiles clustered according to their cellular compartment organization. Protein levels of TLR4 were substantially higher in knee OA than in CMC-I OA, while the opposite was the case at the mRNA level. ELISA assays confirmed the presence of soluble forms of TLR2 and TLR4 in SF, with sTLR4 being considerably higher in CMC-I OA than in knee OA.

Interpretation — We observed that TLRs are differentially expressed in OA cartilage, depending on the joint. Soluble forms of TLR2 and TLR4 were detected for the first time in SF of osteoarthritic joints, with soluble TLR4 being differentially expressed. Together, our results suggest that negative regulatory mechanisms of innate immunity may be involved in the pathomolecular mechanisms of osteoarthritis.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common joint disease. It affects large, weight-bearing joints such as the knees and hips, and also non-weight-bearing joints such as those in the hands.

OA is considered to be a disease of the hyaline cartilage, with disturbed degradation and degeneration of this cartilage mainly occurring because of wear-and-tear injuries caused by mechanical loading of the joint and subsequent inflammatory host responses (Konttinen et al. Citation2012). However, we still barely understand how these pathomechanisms lead to pathophysiological conditions and how are they regulated.

Cartilage degradation, a hallmark of OA, is also a consequence of a compromised ability of resident chondrocytes to maintain tissue homeostasis. Interestingly, OA joint homeostasis is in part mediated by activation of the innate immune system, which is currently viewed as an intrinsic part of the inflammatory cycle of OA (Scanzello et al. Citation2008, Liu-Bryan Citation2013). The critical point about the innate immune system’s role in OA lies in the reaction to the biological, physiological, and mechanical changes in the joint over time. In contrast to the adaptive immune system, innate immunity plays a pivotal role in the host defense against microbial agents, and also in modulation of tissue homoeostasis by recognizing distinct pathogen- and damage-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and DAMPs by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and NOD-like receptors (NLRs) (Chen and Nunez Citation2010). Cartilage degradation products derived either from traumatic injuries or cartilage degeneration may therefore act as DAMPs and consequently activate the local reaction of the innate immune system (Gomez et al. Citation2015). Innate immune activation of inflammatory pathways may induce signaling cascades in chondrocytes, which lead to the upregulation of cartilage matrix-degrading proteases such as MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-13, and ADAMTS aggrecanases while also downregulating aggrecan and collagen type II, a pattern generally seen in the chondrocytic phenotype of OA (Sokolove and Lepus Citation2013).

All members of the TLR family are present in OA cartilage chondrocytes from knee joints (Sillat et al. Citation2013). However, the pathogenesis of OA may be inherently different in different anatomic joints—given the evidence from epidemiology, from genetic and epigenetic studies, and on the impact of risk factors (van Saase et al. Citation1989, Xu et al. Citation2012, den Hollander et al. Citation2014, Thijssen et al. Citation2015). This led us to the hypothesis that the pathogenesis of primary OA, and innate immunity, may vary depending on the location of the joint. We therefore wanted to determine whether smaller joints, such as the first carpometacarpal (CMC-I), have similar knee OA TLR-profile phenotypes. Insight into TLRs, important molecular players in OA, in these 2 different joints might help us to better comprehend joint-specific pathomolecular mechanisms in OA.

Patients and methods

Patient samples

Osteochondral cylinder samples (from 11 women and 4 men) were harvested from tibial plateaus obtained from total knee replacements (TKAs) due to severe knee OA. The mean age of the patients was 67 (52–87) years. These samples were graded for disease severity using the OARSI grading (Pritzker et al. Citation2006).

The mean age of the patients subjected to trapeziectomy, due to severe CMC-I OA, was 58 (43–80) years. All patients had been treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and a thumb spica splint, without pain relief or functional improvement. Severity of the CMC-I OA was assessed using the Eaton-Glickel grading (Eaton and Glickel Citation1987) (Supplementary Figure 1). All patients had non-erosive OA of the CMC-I, confirmed by radiological features (Verbruggen and Veys Citation1996, Altman and Gold Citation2007). OARSI grading could not be performed for CMC-I cartilage samples because trapeziectomy was sometimes only partial, leading to a non-uniform sampling zone, which is essential for OARSI grading. Thus, instead we used the radiological Eaton-Glickel scale to evaluate the disease severity of the CMC-I OA (Eaton and Glickel Citation1987). Radiographs of hand OA correlate positively with the histological assessment of cartilage in post-mortem samples (Sunk et al. Citation2013). It is therefore clear that both scales reflected the severity (i.e. grade) of OA.

The arthritic trapezium bone was excised completely (trapeziectomy) or partially, depending on the presence of OA in the scaphotrapezial joint. None of the patients had Eaton-Glickel grade-I OA, which is a contraindication for arthroplasty. Healthy control cartilage-subchondral bone samples were obtained from the unaffected CMC-III joint, resected from patients undergoing total wrist arthrodesis for posttraumatic OA of the wrist. This joint was included in the wrist fusion to enable plate fixation from the third metacarpal bone to the distal radius. The healthy controls were from 2 men (aged 45 and 53 years). The samples were fixed in neutral-buffered 10% formalin, decalcified in 10% EDTA, pH 7.4, and processed in paraffin. All patients undergoing TKA or trapeziectomy were randomly selected.

Collection of synovial fluid samples

Patients with knee meniscectomy, knee OA, or CMC-I OA were randomly selected for collection of synovial fluid (SF) samples via needle aspiration before opening the joint.

Knee OA SF samples were requested from Biobanco-iMM, Lisbon Academic Medical Center, Lisbon, Portugal. Blood-contaminated SF samples were excluded. SF maintained at 4 °C within a 2-hour window was aliquoted into sterile Eppendorf tubes, centrifuged at 1,200 g for 5 min at room temperature to separate solid debris and cells from the fluid phase, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. When first thawed, SF was treated with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France). Epidemiological data regarding the patients are given in . Selection criteria are described in more detail in Supplementary material.

Table 1. Epidemiological data for patients with healthy knees, knee osteoarthritis (OA) patients, and first carpometacarpal (CMC-I) OA patients

Immunohistochemistry

Articular cartilage samples from CMC-I, CMC-III and knee OA were stained immunohistochemically for TLR1–9, using the avidin-biotin peroxidase method. Briefly, 4-μm tissue sections from CMC-I, knee OA, and CMC-III samples were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was done in 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0, for 1 h at 70 °C. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched in 0.3% H2O2. Sections were blocked with normal goat serum and then incubated (1) overnight at 4 °C in 2 μg/mL TLR1 IgG, 1.1 μg/mL TLR2 IgG, 2 μg/mL TLR3 IgG, 1.3 μg/mL TLR4 IgG, 1.3 μg/mL TLR5 IgG, 1 μg/mL TLR6 IgG, 0.8 μg/mL TLR7 IgG, 1 μg/mL TLR8 IgG, 1 μg/mL TLR9 IgG, and 1.6 μg/mL TLR10 IgG (rabbit anti-human antibodies; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), (2) in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Vectorlabs, Burlingame, CA), and (3) in avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex. Color was developed using H2O2 and 3,3’-diaminobenzidine for 10 min, followed by counterstaining with Mayer hematoxylin. Incubations were performed at 22 °C, with PBS washes in-between the steps unless otherwise stated. The samples on slides were dehydrated, cleared, and mounted. Knee OA samples were used as positive controls. For negative staining controls, non-immune IgG was used instead of—and at the same concentration as—the primary specific antibodies.

Microscopy and histomorphometry

Stained samples were evaluated microscopically. For histomorphometric calculations, the percentages of TLR-positive cells were evaluated from 5 high-power fields (magnification 200×) from each area of interest.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated from equivalent-graded frozen cartilage samples from CMC-I patients (n = 10) and knee OA patients (n = 10) using the RNAqueous kit (Life Technologies) and following the manufacturer’s protocol. Relative quantification of the gene levels was performed by comparing the Ct values of the TLR4 gene, correcting for TATA-binding protein (TBP) content (ΔCt). Relative expression levels are given.

The mRNA was extracted from frozen cartilage samples since formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples are prone to mRNA degradation.

ELISA

SF was measured for soluble TLR2 and soluble TLR4 molecules using specific sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Uscn Life Science, Hubei, PRC). Assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were run in duplicate and absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

Statistics

Differences between groups were tested using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test or the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test, as appropriate. Principal component analyses (PCA) allows easy overview of a large dataset by reducing the dimensionality of the data while retaining the variation present in the original dataset. Despite being used initially and primarily in large populations of patients, PCA has similar noise-reducing properties in small populations. The Eigen value 1 criterion was used to select the appropriate number of principal components (PCs), i.e. PCs with Eigenvalue >1. Loading values vary from −1 to 1 and are interpreted as the degree of variable correlation within each PC. Missing data cases were excluded list-wise. Both oblique promax and orthogonal varimax rotations were examined, and produced similar results. PCA was performed using SPSS version 22.0 software. All the other statistical analyses were performed using this software.

Ethics and funding

The study protocol was accepted by the local ethics committee (Dnro_59/13/03/02/2013).

This work was supported by ORTON Orthopaedic Hospital of the Invalid Foundation, Finska Läkaresällskapet, HUS Evo grants, the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation, and the Maire Lisko Foundation. The funding sponsors had no other role in the current study.

Results

Immunohistochemistry

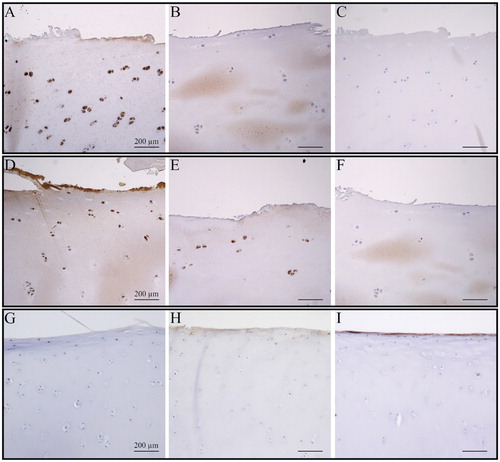

Our immunohistochemistry results confirmed the expression of several TLRs in cartilage from different CMC-I OA grades, which was in line with the observed expression in cartilage from knee OA ().

Figure 1. TLR3 and TLR4 expression in cartilage from hand and knee OA joints. A–C. Eaton-Glickel grade-2 CMC-I OA stained for TLR3 and TLR4, together with a negative staining control (panel C). D–F. OARSI grade-2 knee OA stained for TLR3 and TLR4, together with a negative staining control (panel F). G–I, healthy control CMC-III stained for TLR3 and TLR4, together with a negative staining control (panel I). Magnification: 100×.

However, histomorphometric analysis revealed that TLRs followed distinctive and rather heterogeneous expression patterns, in contrast to the homogenous expression patterns of TLRs in knee OA cartilage (; TLR expression data from knee not shown).

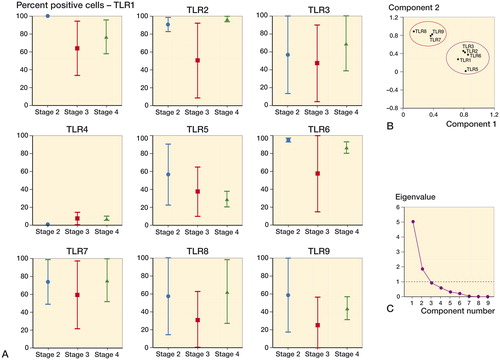

Figure 2. Histomorphometric and principal component analysis (PCA) of toll-like receptor protein expression in cartilage from CMC-I OA patients. A. TLR expression was heterogeneous with no statistical significance during progression between stages. CMC-I OA cartilage degradation stages were graded according to the Eaton-Glickel radiological score. Results are expressed as mean and SD. For each SFA score, n = 4. B. PCA of the histomorphometric TLR data in OA of the CMC-I joint. 95% confidence ellipsoids drawn from PCA show a clear separation of the TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9 cluster from the TLR1, TLR2, TLR3, and TLR5 cluster—and that TLR4 had no association with either. Loading values varied from −1 to 1 and represent correlation of the variable with the principal components (PCs). Cases with missing data were excluded list-wise. Oblique promar and orthoganal varimax rotations gave similar results. C. The eigen value 1 criterion was used to select the PCs.

PCA was performed on CMC-I histomorphometric data to assess the relationships of individual TLR variables across the entire dataset. PC1 and PC2 disclosed 2 clusters separated by 95% confidence ellipsoids, 1 cluster being composed of TLRs 1–3, TLR5, and TLR6, while the other was composed of TLRs 7–9. PC1 and PC2 represented 76% of the data (56% and 21%, respectively). TLR4 was unequivocally separated from clusters and correlated negatively with the higher expression of all the other TLRs ().

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

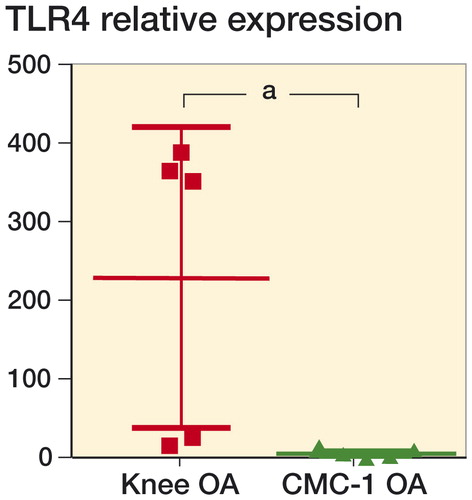

In contrast to protein levels of TLR 4, the relative levels of expression of TLR4 mRNA were higher in CMC-I OA cartilage than in knee OA cartilage ().

Figure 3. Relative TLR4 mRNA expression in CMC-I and knee OA cartilage. The expression was markedly higher in CMC-I OA cartilage than in knee OA cartilage. The results are expressed as mean and SD. a p < 0.01 indicates statistically significant differences between pairwise comparison groups using the Mann-Whitney test (non-parametric). Data were obtained from 10 patients with each OA joint type, and run in duplicate.

ELISA

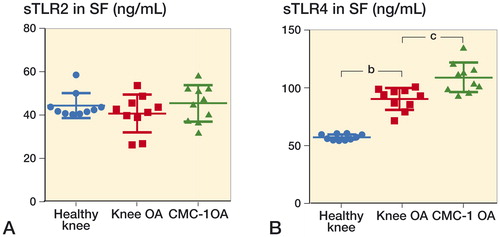

Given the different mRNA and protein expression levels of TLR4 in CMC-I and knee OA joints, we hypothesized that such differences might be explained, in part, by solubilization of TLR4 protein. sTLR4 ELISA analysis of SF obtained from both joints revealed that sTLR4 forms were present, and in significantly different concentrations ().

Figure 4. Scatter plot of synovial fluid concentrations of sTLR2 and sTLR4 in different arthritic conditions. A. Synovial fluid levels of sTLR2 were rather homogenous in healthy knee, knee OA, CMC-I OA patients. B. Synovial fluid levels of sTLR4 were significantly higher in CMC-I OA, followed by lower levels in knee OA and even lower levels in healthy knees. Each dot represents 1 sample. Mean values (± SD). SF samples were obtained from 10 patients in each group. b p < 0.005, c p < 0.001, indicating statistically significant differences between pairwise comparisons using the Kruskal-Wallis test (non-parametric).

Solubilization of TLR2 (the only other TLR that is known to be soluble) was also analyzed. We detected similar, small concentrations of sTLR2 in the different arthritic groups ().

Discussion

We have shown here for the first time that TLR expression in OA cartilage follows expression patterns that are dependent on the joint affected. This suggests that the pathophysiological mechanisms regulating OA may differ according to joint type. Our findings show that healthy chondrocytes resident in cartilage from CMC-I and knee joints have a limited expression of TLRs, in accordance with earlier reports on TLR2 and TLR4 (Kim et al. Citation2006). However, as the depth of progression of OA increases through cartilage (OARSI grade definition), TLR expression follows different patterns depending of the type of joint. In knee OA, we observed an analogous increase in TLR expression as the severity increased, in line with a recent study from our group (Barreto et al. Citation2013). On the other hand, in CMC-I OA, TLR expression was heterogeneous and patient-dependent. Given the heterogeneous CMC-I histomorphometric data, we used PCA in order to determine whether protein-specific expression patterns were present. PCA revealed a clear clustering of TLRs that can form heterodimeric complexes at the surface of the cell (TLR1, 2, 5, and 6), in parallel with the clustering of the endosomal TLRs (TLR7, 8, and 9). In general, all these MyD88-dependent TLRs co-operate with each other (O’Neill et al. Citation2013). Secondly, TLR3 clustered together with the cell surface TLRs. Unlike the previously mentioned TLRs, TLR3 exclusively uses a TRIF-dependent signaling pathway. The association of TLR3 with TLR2 might have functional consequences, given their synergistic proinflammatory effects that mediate a "2-hit" trigger (Vanhoutte et al. Citation2008). TLR4 is the only TLR to use both MyD88 and TRIF signaling, and our results have shown that it is unequivocally distinct from other TLRs. Notably, TLR4 protein expression remained consistently low in all CMC-I samples, in striking contrast to the high degree of expression in knee OA samples.

The reasons for the observed difference in TLR expression in CMC-I and knee OA joints may relate to the common and specific factors known to be associated with hand and knee OA joints. Risk factors such as obesity, for example, may be involved. Obesity is known to double the likelihood of hand OA (Yusuf et al. Citation2010). However, given that hand OA occurs in a non-weight-bearing joint, obesity-related systemic factors other than mechanical overload—such as adipokines—may be involved (Berenbaum et al. Citation2013, Thijssen et al. Citation2015). Adipokines are not only present systemically but are also present in OA joint SF at pathophysiological concentrations (Staikos et al. Citation2013). Adipokines have been shown to have anti- and proinflammatory properties but have also been found to regulate TLR expression and vice versa (Batra et al. Citation2007, Kopp et al. Citation2009). In the present study, BMI levels were similar in both the CMC-I OA and knee OA patient groups ().

Genetic and epigenetic differences between the 2 joints may play an important role in activation of the innate immunity, and consequently TLR expression. Several risk-conferring loci for hip, knee, and hand OA have recently been identified through genome-wide association study (GWAS) efforts. This information also showed that certain loci are associated with certain joints only, further highlighting the need for joint stratification when studying OA (Reynard and Loughlin. Citation2013, Styrkarsdottir et al. Citation2014). Moreover, a recent study demonstrated that certain loci located in/near TGFA (transforming growth factor alpha) are associated with cartilage thickness in OA knee and hip joints (Castano-Betancourt et al. Citation2016). In the CMC-I joint, cartilage thickness is thinner than knee and hip cartilage; moreover, TGFA is known to have regulatory effects on TLR expression (Miller et al. Citation2005). Interestingly, TLR3 and TLR9 polymorphisms are associated with severe knee OA (Su et al. Citation2012, Yang et al. Citation2013). The association of TLR polymorphisms with other OA joints, such as hand OA, remains to be investigated.

Since the differences in the patterns of TLR4 protein expression might have arisen from regulation of gene expression, we examined the TLR4 mRNA levels in cartilage samples from CMC-I OA patients and knee OA patients. Surprisingly, TLR4 mRNA levels were substantially higher in CMC-I OA than in knee OA. The fact that there was dysregulation in expression of TLR4 mRNA and TLR4 protein was an important finding. TLR4 is one of the main innate immune receptors; it recognizes several endogenous ligands present in OA joints, such as fibronectin and S100A8/A9 (Gomez et al. Citation2015).

Nevertheless, the current findings lead us to believe that

CMC-I OA TLR4 protein expression was being downregulated, possibly as an attempt to control TLR4. Interestingly, in acute renal injury—where the integrity of the extracellular matrix (ECM) is compromised—it was observed that increase in TLR4 mRNA was not preceded by an increase in TLR4 protein expression. Instead, extracellular TLR4 was being released via a solubilization mechanism (Zager et al. Citation2007). This biological response occurs by soluble ligand-binding neutralization and/or decreased surface apical expression, preventing further ligand binding to TLR4 at the cell membrane, and consequently activation of TLR4 signaling. Amniotic fluid, saliva, blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and kidney and liver are examples of body fluids/organs where increased release of soluble TLR4 has been observed (Mitsuzawa et al. Citation2006, Zager et al. Citation2007, Kacerovsky et al. Citation2012, Uchimura et al. Citation2014, Sokol et al. Citation2016). Interestingly, sTLR4 has also been proposed as a potential systemic biomarker for inflammatory conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis (Ten Oever et al. Citation2014). We hypothesized that such a mechanism might also occur in TLR-equipped tissues of the OA joints. In particular, increased solubilization of TLR4 in the CMC-I joint would explain the discrepancies between the mRNA and the protein data.

Indeed, we did detect sTLR4 forms in SF from knee and CMC-I arthritic joints, with statistically significantly higher concentrations in SF from CMC-I OA than in SF from knee OA. Such differences in concentration levels might then explain the reduced TLR4 protein expression observed in cartilage from CMC-I OA joints. It is therefore possible to envision an increase in solubilization of sTLR4 (reducing surface protein expression) as a way of negatively regulating the known increase in the presence of TLR4-specific endogenous ligands in SF from OA and other inflammatory arthritis (van Lent et al. Citation2012, Nair et al. Citation2012). Similarly, others have reported increased concentrations of endogenous ligand MRP18/4 in plasma and reduced TLR4 expression (Rahman et al. Citation2014). The fact we detected soluble forms of TLR2 and TLR4, with the latter being differentially regulated, is further evidence of the importance of TLR4 in inflammatory components/mechanisms associated with OA, which shape the OA disease concept (Houard et al. Citation2013, Gomez et al. Citation2015). Surprisingly, sTLR4 allowed us to discriminate between healthy knee and knee OA, thus implicating sTLR4 as a potential candidate biomarker for OA studies. The mechanism by which such TLR4 solubilization occurs (alternative splicing and/or proteolytic cleavage) was not addressed in these experiments and it is still unclear how this occurs.

In summary, epidemiological, genetic, and biomarker-related associations between hand OA and other OA joints have been intensely studied, and associations have also been found. Even so, few studies have confirmed that extensive common pathomechanisms occur in the different OA joints. Our findings at this early stage confirm the hypothesis that the expression of TLRs is inherently different in knee OA and CMC-I OA, particularly for TLR4, which would also suggest that major differences exist in the innate immunity mechanisms that drive OA in different joints. Our results add an extra piece of evidence to the current literature stressing that the "disease process" of OA is unlikely to be uniform across all synovial joints of the body.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available in the online version of the article.

We thank the Biobanco-IMM in Lisbon, Portugal for providing us with the knee SF samples from OA and RA patients, which were used for ELISA analysis.

GB and EW: conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, data analysis, interpretation of data, and writing of the manuscript. JS: acquisition and interpretation of data, and writing of the manuscript. AS: interpretation of data and writing of the manuscript. DN: conception and design of the study, interpretation of data, and writing of the manuscript.

IORT_A_1281058_SUPP.PDF

Download PDF (570.8 KB)- Altman R D, Gold G E. Atlas of individual radiographic features in osteoarthritis, revised. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2007; 15SupplA: A1–56.

- Barreto G, Sillat T, Soininen A, Ylinen P, Salem A, Konttinen Y T, Al-Samadi A, Nordstrom D C. Do changing toll-like receptor profiles in different layers and grades of osteoarthritis cartilage reflect disease severity? J Rheumatol 2013; 40 (5): 695–702.

- Batra A, Pietsch J, Fedke I, Glauben R, Okur B, Stroh T, Zeitz M, Siegmund B. Leptin-dependent toll-like receptor expression and responsiveness in preadipocytes and adipocytes. Am J Pathol 2007; 170 (6): 1931–41.

- Berenbaum F, Eymard F, Houard X. Osteoarthritis, inflammation and obesity. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2013; 25 (1): 114–8.

- Castano-Betancourt M C, Evans D S, Ramos Y F, Boer C G, Metrustry S, Liu Y, den Hollander W, van Rooij J, Kraus V B, Yau M S, Mitchell B D, Muir K, Hofman A, Doherty M, Doherty S, Zhang W, Kraaij R, Rivadeneira F, Barrett-Connor E, Maciewicz R A, Arden N, Nelissen R G, Kloppenburg M, Jordan J M, Nevitt M C, Slagboom E P, Hart D J, Lafeber F, Styrkarsdottir U, Zeggini E, Evangelou E, Spector T D, Uitterlinden A G, Lane N E, Meulenbelt I, Valdes A M, van Meurs J B. Novel genetic variants for cartilage thickness and hip osteoarthritis. PLoS Genet 2016; 12 (10): e1006260.

- Chen G Y, Nunez G. Sterile inflammation: Sensing and reacting to damage. Nat Rev Immunol 2010; 10 (12): 826–37.

- den Hollander W, Ramos Y F, Bos S D, Bomer N, van der Breggen R, Lakenberg N, de Dijcker W J, Duijnisveld B J, Slagboom P E, Nelissen R G, Meulenbelt I. Knee and hip articular cartilage have distinct epigenomic landscapes: Implications for future cartilage regeneration approaches. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73 (12): 2208–12.

- Eaton R G, Glickel S Z. Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. staging as a rationale for treatment. Hand Clin 1987; 3 (4): 455–71.

- Gomez R, Villalvilla A, Largo R, Gualillo O, Herrero-Beaumont G. TLR4 signalling in osteoarthritis-finding targets for candidate DMOADs. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2015; 11(3): 159–70.

- Houard X, Goldring M B, Berenbaum F. Homeostatic mechanisms in articular cartilage and role of inflammation in osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2013; 15 (11): 375,013–0375-6.

- Kacerovsky M, Andrys C, Hornychova H, Pliskova L, Lancz K, Musilova I, Drahosova M, Bolehovska R, Tambor V, Jacobsson B. Amniotic fluid soluble toll-like receptor 4 in pregnancies complicated by preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012; 25 (7): 1148–55.

- Kim H A, Cho M L, Choi H Y, Yoon C S, Jhun J Y, Oh H J, Kim H Y. The catabolic pathway mediated by toll-like receptors in human osteoarthritic chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54 (7): 2152–63.

- Konttinen Y T, Sillat T, Barreto G, Ainola M, Nordstrom D C. Osteoarthritis as an autoinflammatory disease caused by chondrocyte-mediated inflammatory responses. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64 (3): 613–6.

- Kopp A, Buechler C, Neumeier M, Weigert J, Aslanidis C, Scholmerich J, Schaffler A. Innate immunity and adipocyte function: Ligand-specific activation of multiple toll-like receptors modulates cytokine, adipokine, and chemokine secretion in adipocytes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009; 17 (4): 648–56.

- Liu-Bryan R. Synovium and the innate inflammatory network in osteoarthritis progression. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2013; 15 (5): 323,013–0323-5.

- Miller L S, Sorensen O E, Liu P T, Jalian H R, Eshtiaghpour D, Behmanesh B E, Chung W, Starner T D, Kim J, Sieling P A, Ganz T, Modlin R L. TGF-alpha regulates TLR expression and function on epidermal keratinocytes. J Immunol 2005; 174 (10): 6137–43.

- Mitsuzawa H, Nishitani C, Hyakushima N, Shimizu T, Sano H, Matsushima N, Fukase K, Kuroki Y. Recombinant soluble forms of extracellular TLR4 domain and MD-2 inhibit lipopolysaccharide binding on cell surface and dampen lipopolysaccharide-induced pulmonary inflammation in mice. J Immunol 2006; 177 (11): 8133–9.

- Nair A, Kanda V, Bush-Joseph C, Verma N, Chubinskaya S, Mikecz K, Glant T T, Malfait A M, Crow M K, Spear G T, Finnegan A, Scanzello C R. Synovial fluid from patients with early osteoarthritis modulates fibroblast-like synoviocyte responses to toll-like receptor 4 and toll-like receptor 2 ligands via soluble CD14. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64 (7): 2268–77.

- O’Neill L A, Golenbock D, Bowie A G. The history of toll-like receptors - redefining innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2013; 13 (6): 453–60.

- Pritzker K P, Gay S, Jimenez S A, Ostergaard K, Pelletier J P, Revell P A, Salter D, van den Berg W B. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: Grading and staging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2006; 14 (1): 13–29.

- Rahman M T, Myles A, Gaur P, Misra R, Aggarwal A. TLR4 endogenous ligand MRP8/14 level in enthesitis-related arthritis and its association with disease activity and TLR4 expression. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014; 53 (2): 270–4.

- Reynard L N, Loughlin J. The genetics and functional analysis of primary osteoarthritis susceptibility. Expert Rev Mol Med 2013; 15: e2.

- Scanzello C R, Plaas A, Crow M K. Innate immune system activation in osteoarthritis: Is osteoarthritis a chronic wound? Curr Opin Rheumatol 2008; 20 (5): 565–72.

- Sillat T, Barreto G, Clarijs P, Soininen A, Ainola M, Pajarinen J, Korhonen M, Konttinen Y T, Sakalyte R, Hukkanen M, Ylinen P, Nordstrom D C. Toll-like receptors in human chondrocytes and osteoarthritic cartilage. Acta Orthop 2013; 84 (6): 585–92.

- Sokol B, Wasik N, Jankowski R, Holysz M, Wieckowska B, Jagodzinski P. Soluble toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with acute hydrocephalus following aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. PLoS One 2016; 11 (5): e0156171.

- Sokolove J, Lepus C M. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: Latest findings and interpretations. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2013; 5 (2): 77–94.

- Staikos C, Ververidis A, Drosos G, Manolopoulos V G, Verettas D A, Tavridou A. The association of adipokine levels in plasma and synovial fluid with the severity of knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013; 52 (6): 1077–83.

- Styrkarsdottir U, Thorleifsson G, Helgadottir H T, Bomer N, Metrustry S, Bierma-Zeinstra S, et al. Severe osteoarthritis of the hand associates with common variants within the ALDH1A2 gene and with rare variants at 1p31. Nat Genet 2014; 46 (5): 498–502.

- Su S L, Yang H Y, Lee C H, Huang G S, Salter D M, Lee H S. The (-1486T/C) promoter polymorphism of the TLR-9 gene is associated with end-stage knee osteoarthritis in a chinese population. J Orthop Res 2012; 30 (1): 9–14.

- Sunk I G, Amoyo-Minar L, Niederreiter B, Soleiman A, Kainberger F, Smolen J S, Bobacz K. Histopathological correlation supports the use of x-rays in the diagnosis of hand osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72 (4): 572–7.

- Ten Oever J, Kox M, van de Veerdonk F L, Mothapo K M, Slavcovici A, Jansen T L, Tweehuysen L, Giamarellos-Bourboulis E J, Schneeberger P M, Wever P C, Stoffels M, Simon A, van der Meer J W, Johnson M D, Kullberg B J, Pickkers P, Pachot A, Joosten L A, Netea M G. The discriminative capacity of soluble toll-like receptor (sTLR)2 and sTLR4 in inflammatory diseases. BMC Immunol 2014; 15: 55,014–0055-y.

- Thijssen E, van Caam A, van der Kraan P M. Obesity and osteoarthritis, more than just wear and tear: Pivotal roles for inflamed adipose tissue and dyslipidaemia in obesity-induced osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015; 54 (4): 588–600.

- Uchimura K, Hayata M, Mizumoto T, Miyasato Y, Kakizoe Y, Morinaga J, Onoue T, Yamazoe R, Ueda M, Adachi M, Miyoshi T, Shiraishi N, Ogawa W, Fukuda K, Kondo T, Matsumura T, Araki E, Tomita K, Kitamura K. The serine protease prostasin regulates hepatic insulin sensitivity by modulating TLR4 signalling. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 3428.

- van Lent P L, Blom A B, Schelbergen R F, Sloetjes A, Lafeber F P, Lems W F, Cats H, Vogl T, Roth J, van den Berg W B. Active involvement of alarmins S100A8 and S100A9 in the regulation of synovial activation and joint destruction during mouse and human osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64 (5): 1466–76.

- van Saase J L, van Romunde L K, Cats A, Vandenbroucke J P, Valkenburg H A. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: Zoetermeer survey. comparison of radiological osteoarthritis in a dutch population with that in 10 other populations. Ann Rheum Dis 1989; 48 (4): 271–80.

- Vanhoutte F, Paget C, Breuilh L, Fontaine J, Vendeville C, Goriely S, Ryffel B, Faveeuw C, Trottein F. Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR3 synergy and cross-inhibition in murine myeloid dendritic cells. Immunol Lett 2008; 116 (1): 86–94.

- Verbruggen G, Veys E M. Numerical scoring systems for the anatomic evolution of osteoarthritis of the finger joints. Arthritis Rheum 1996; 39 (2): 308–20.

- Xu Y, Barter M J, Swan D C, Rankin K S, Rowan A D, Santibanez-Koref M, Loughlin J, Young D A. Identification of the pathogenic pathways in osteoarthritic hip cartilage: Commonality and discord between hip and knee OA. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2012; 20 (9): 1029–38.

- Yang H Y, Lee H S, Lee C H, Fang W H, Chen H C, Salter D M, Su S L. Association of a functional polymorphism in the promoter region of TLR-3 with osteoarthritis: A two-stage case-control study. J Orthop Res 2013; 31 (5): 680–5.

- Yusuf E, Nelissen R G, Ioan-Facsinay A, Stojanovic-Susulic V, DeGroot J, van Osch G, Middeldorp S, Huizinga T W, Kloppenburg M. Association between weight or body mass index and hand osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis 2010; 69 (4): 761–5.

- Zager R A, Johnson A C, Lund S, Randolph-Habecker J. Toll-like receptor (TLR4) shedding and depletion: Acute proximal tubular cell responses to hypoxic and toxic injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2007; 292 (1): F304–12.