Abstract

Background and purpose — Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are increasingly used to evaluate results in orthopedic surgery. To enhance good responsiveness with a PROM, the minimally important change (MIC) should be established. MIC reflects the smallest measured change in score that is perceived as being relevant by the patients. We assessed MIC for the Self-reported Foot and Ankle Score (SEFAS) used in Swedish national registries.

Patients and methods — Patients with forefoot disorders (n = 83) or hindfoot/ankle disorders (n = 80) completed the SEFAS before surgery and 6 months after surgery. At 6 months also, a patient global assessment (PGA) scale—as external criterion—was completed. Measurement error was expressed as the standard error of a single determination. MIC was calculated by (1) median change scores in improved patients on the PGA scale, and (2) the best cutoff point (BCP) and area under the curve (AUC) using analysis of receiver operating characteristic curves (ROCs).

Results — The change in mean summary score was the same, 9 (SD 9), in patients with forefoot disorders and in patients with hindfoot/ankle disorders. MIC for SEFAS in the total sample was 5 score points (IQR: 2–8) and the measurement error was 2.4. BCP was 5 and AUC was 0.8 (95% CI: 0.7–0.9).

Interpretation — As previously shown, SEFAS has good responsiveness. The score change in SEFAS 6 months after surgery should exceed 5 score points in both forefoot patients and hindfoot/ankle patients to be considered as being clinically relevant.

Outcome after surgery has traditionally been assessed with physician-derived parameters, but over the past decade analyses have been more patient-centered with the use of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) evaluating pain, function, and quality of life (QoL) (Suk Citation2009). The Self-reported Foot and Ankle Score (SEFAS) is a foot- and ankle-specific PROM used in the Swedish National Ankle Registry since 2008, which includes ankle prostheses and ankle fusions performed in Sweden (Coster et al. Citation2012). The SEFAS is also used in the recently established National Swedish Foot and Ankle Registry (www.riksfot.se), where the most common diagnoses and surgical procedures in the foot and/or ankle performed in Sweden are included. The SEFAS has good measurement properties regarding validity, reliability, and responsiveness in patients with a variety of foot and ankle disorders (Coster et al. Citation2012, Citation2014a, Citation2014b, Citation2015). In addition to these properties, it is also important to interpret the changes in scores of the PROM as a measure of treatment effect and clinical importance. The minimally important change (MIC) reflects the smallest measured change in score that patients perceive as being important. MIC is of value to define a threshold when a treatment should be regarded as clinically relevant, which gives us a better possibility of using the PROM for evaluating individual patients (van Kampen et al. Citation2013, Sierevelt et al. Citation2016). However, MIC values can be calculated in various ways. Anchor-based methods assess what changes in the score correspond to a minimally important change defined on an anchor, i.e. an external criterion. The anchor-based methods are most frequently used, but no consensus on the method of MIC measurement has been achieved (Beaton et al. Citation2002, Copay et al. Citation2007, Sorensen et al. Citation2013).

The MIC value of the SEFAS has yet not been evaluated. We therefore evaluated the MIC together with the measurement error and the responsiveness for SEFAS in patients with disorders of the forefoot or the hindfoot/ankle.

Patients and methods

Subjects and study design

In this prospective study, we consecutively recruited patients who were scheduled for surgery of the foot or ankle at the orthopedic departments of 2 Swedish county hospitals during the period January 1, 2011 through September 30, 2013. We recruited 83 patients (73 of them women) with a median age of 57 (16–87) years with disorders of the forefoot and 80 patients (47 of them women) with a median age of 56 (18–81) with disorders of the hindfoot and/or ankle (). All participants completed the SEFAS score before and 6 months after surgery. After 6 months, they also completed a patient global assessment (PGA) scale. For the evaluation of measurement error, 62 patients with disorders of the forefoot and 71 patients with disorders of the hindfoot/ankle also completed the SEFAS twice within 2 weeks. The patients in this study were a subgroup of the patients included in our previous validation studies (Coster et al. Citation2014a, Citation2014b).

Table 1. General and anthropometric data for all the patients included

The Self-reported Foot and Ankle Score (SEFAS)

The SEFAS is a foot- and ankle-specific PROM based on the New Zealand total ankle questionnaire (Hosman et al. Citation2007). The SEFAS contains 12 questions with 5 response options scored from 0 to 4, where a sum of 0 points represents the most severe disability and 48 represents normal function. The PROM has no subscores, but covers different important constructs such as pain, function, and activity limitations. The SEFAS has good measurement properties for evaluating both patients with forefoot disorders and patients with hindfoot/ankle disorders (Coster et al. Citation2012, Citation2014a, Citation2014b, Citation2015).

Anchor-based methods

Anchor-based methods evaluate how a change in the total score of a PROM relates to an external criterion (anchor). The anchor commonly consists of a patient global assessment (PGA) rating scale, in which the patients are asked—in a single question at follow-up—how they rate themselves after surgery (Hagg et al. Citation2003). The PGA scale in the present study consisted of the responses to a question about the patient’s opinion of the result of surgery: “Have you improved after surgery?”. The 5 possible responses to the question were (1) completely recovered, (2) much improved, (3) improved, (4) unchanged, and (5) worse. We evaluated the relationship between the PGA scales and changes in total score of the SEFAS from before surgery to 6 months after surgery. Operations in the forefoot may differ from those in the hindfoot and ankle, but the function and pain are affected in a similar way, which makes it possible to use the SEFAS for both groups of patients and to evaluate the changes in the score in relation to an anchor (Coster et al. Citation2014a, Citation2014b).

Statistics

Responsiveness, the ability to detect change over time, was calculated by using the effect size (ES). ES was calculated as the difference between the means before and after treatment, divided by the pre-treatment standard deviation (SD) of that measure. ES values of >0.80 are considered to be large, 0.50–0.80 to be moderate, 0.20–0.49 small, and <0.2 trivial (Cohen Citation1978). The confidence intervals (CIs) for ES were calculated according to Becker (Citation1988). These CIs were calculated assuming a normal distribution, which was verified. The measurement error was calculated as the intra-individual variability of the functional measures expressed as standard error of a single determination (Smethod), together with the coefficient of variation (CV in %) for the score. The equation for the calculation of Smethod is: Smethod = √ (Σdi2/(2n)), where di is the difference between the ith paired measurement and n is the number of differences, and the CV% is calculated as the Smethod divided by the overall mean (Dahlberg Citation1940). MIC was calculated as the median change in SEFAS in patients who identified themselves to be “improved” on the PGA scale. We performed the same analyses for the group of patients who answered “much improved” together with “completely recovered”, and the patients who answered “worse”.

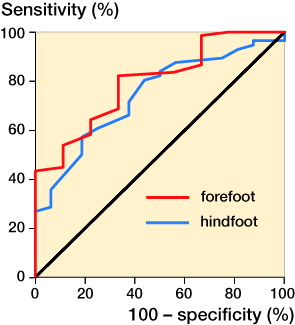

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were also used to discriminate between the patients who did or did not experience improvement. ROC curves plot sensitivity (on the y-axis) against 1 − specifity (on the x-axis) for all possible cutoff points of the change score of the PROM evaluated, and relate this to the probability of detecting improved patients according to the anchor, the PGA scale. The most efficient cutoff value with regard to sensitivity and specificity, i.e. the best cutoff point (BCP), is associated with the point closest to the top left-hand corner of the ROC curve. The area under curve (AUC) of a ROC curve represents the probability that the PROM will correctly discriminate between improved and unimproved patients. An area of 0.5 is purely random. An area of 0.7 to 0.8 is acceptable, and an area of 0.8–0.9 is excellent provided the AUC is statistically significantly greater than 0.5 (Terluin et al. Citation2015).

Statistical calculations were performed with SPSS for Windows version 23.0 and Statistica version 12. MedCalc Statistical Software version 16.8.4 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium; https://www.medcalc.org; 2016) was used for ROC curve analysis.

Ethics

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Lund University, Sweden (2009/698) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was obtained from the participants.

Results

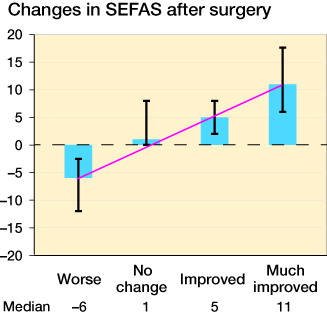

Change in mean SEFAS score 6 months after surgery in patients with forefoot disorders was 9 (SD 9), and in patients with hindfoot/ankle disorders it was 9 (SD 9). The ES was large in forefoot patients (1.2, 95% CI: 0.9–1.5) and in hindfoot/ankle patients (1.1, 95% CI: 0.8–1.4). The measurement error according to Smethod was 2.4 in forefoot patients and 2.5 in hindfoot/ankle patients, and corresponding values for CV% were 8 and 12. MIC median values for SEFAS were 5 (IQR: −5 to 8) in forefoot patients and 5 (IQR: 3–9) in hindfoot/ankle patients (). Median changes in SEFAS 6 months after surgery by response categories on the PGA scale are presented in . BCP in the ROC curve was 5 and AUC was 0.8 (95% CI: 0.7–0.9) in forefoot patients. The corresponding values in hindfoot/ankle patients were 7 and 0.7 (95% CI: 0.6–0.9). The AUC showed that the SEFAS had an acceptable probability of discriminating between improved and unimproved patients ( and ).

Figure 1. Median changes in SEFAS score and lower and upper quartiles (y-axis) in relation to the response to the anchor question in the PGA scale (x-axis). The table above shows median values.

Table 2. Mean preoperative and 6-month postoperative change scores, effect size (ES), measurement error, and summary of estimates for the minimally important change (MIC) for SEFAS in patients with disorders of the forefoot or the ankle/hindfoot. Best cutoff point (BCP) and area under the curve (AUC) with CIs are derived from a ROC analysis

Discussion

We found that the SEFAS can adequately discriminate between improved and unimproved patients 6 months after surgery, which is useful clinical information. The smallest measured change score that patients perceived as being relevant, the MIC, was 5 score points out of 48 in patients with forefoot and/or hindfoot/ankle disorders. Also, the SEFAS showed good responsiveness with large effect sizes and acceptable measurement errors.

PROMs are increasingly used in research and also in national registries to evaluate the effectiveness of orthopedic surgery (Rolfson et al. Citation2016). Before using a PROM in research studies, the measurement properties of the instrument must be assessed (Terwee et al. Citation2007). The consensus-based standards for the selection of health measurement instruments (COSMIN) group has developed a checklist that is internationally accepted when PROMs are created and assessed (Mokkink et al. Citation2010a, Citation2010b). The COSMIN group requires that 3 properties should be distinguished and evaluated: (1) validity; (2) reliability, including measurement error; and (3) responsiveness (Mokkink et al. Citation2016). To date, all the data from the validation process of SEFAS support its use in national registries, and also in clinical practice for individual evaluations and in research.

In addition to the properties already described, it is important to know that the changes in scores are interpretable (de Vet et al. Citation2010). The COSMIN group recommends that the minimally important change or difference, as an attribute of the interpretability of a PROM, should be established. However, the COSMIN group does not suggest any specific methodology (Mokkink et al. Citation2010a, Citation2010b). There are different terms used in estimating minimal change or difference. A value representing the minimally important change (MIC) is the most appropriate estimate when the intention is to measure changes over time within individuals or groups (de Vet et al. Citation2010, Dawson et al. Citation2014, Beard et. al 2015). De Vet et al. (Citation2010) recommended using the term MIC in clinical practice for measuring changes within patients, and we have adhered to this terminology. However, a MIC used at the individual level and at the group level is the same, but the uncertainties are greater at the individual level and some caution in interpretation is needed (de Vet et al. Citation2010). The confidence intervals (CIs) can give an indication of the precision of the MIC. In our study population, we found that the 95% CIs for AUC were in the range of 0.6–0.9, which can partly be explained by the low number of patients included.

To establish the MIC, BCP, and AUC, we chose anchor-based methods. Distribution-based methods have also been presented and used in comparable publications. These methods are based on statistical measures unrelated to change perceived by the patient (Wyrwich et al. Citation2013). In contrast, anchor-based methods cover the clinical importance of change scores in relation to a PGA scale. These last methods have recently been recommended (de Vet et al. Citation2010).

During the past few decades, considerable research has been done to establish MIC values for different PROMs, to increase their usability. The MIC has been established for several PROMs used in orthopedic registries, such as the Oxford hip and knee scores (OHS/OKS), the Manchester-Oxford foot questionnaire (MOXFQ), and the foot and ankle outcome score (FAOS) (Dawson et al. Citation2014, Beard et al. Citation2015, Siervelt et al. 2016).

The main limitation of the present study was the heterogeneity of the cohort. The cohort represents different diagnoses and is divided into subgroups, which makes the sample sizes small. However, the findings from the PGA scale including improved and much improved patients show a linear change in scores and support our general findings. The heterogeneity might also be viewed as being a strength. The advantage of using a cohort with heterogeneity is that it means that the MIC value can be used in different kinds of foot and ankle disorders. Our findings are comparable to results from patients with forefoot and hindfoot disorders published by Muradin and van der Heide (Citation2016). Future studies should be carried out to establish whether the MIC values vary in different subgroups. Establishment of the validity and reliability of a PROM is an ongoing process, and it should be assessed in different groups of patients and in different types of interventions (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research et al. 2006). Recently, the validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the SEFAS was evaluated with good results both in patients with forefoot disorders and in patients with hindfoot and/or ankle disorders (Coster et al. Citation2012, Citation2014a, 2914b, Citation2015). An important strength of this study is that a reliable MIC value has been established for the same cohort of patients included in earlier validation studies (Coster et al. Citation2012, Citation2014a, Citation2014b, Citation2015), which makes the PROM suitable for registries and also useful in daily clinical practice.

In summary, as shown in our previous studies, the SEFAS has a good ability to detect changes over time. We found that a change in SEFAS of greater than 5 score points at 6-month follow-up is of clinical relevance. The SEFAS adequately discriminates between improved and unimproved patients and can be used when evaluating patient-reported outcome after surgery in the forefoot, hindfoot, and ankle.

Financial support for this study was received from the Research Council in Southeast Sweden (FORSS), Herman Järnhardts Stiftelse, the Swedish Foot and Ankle Society, and Stiftelsen Skobranschens utvecklingsfond.

MCC contributed to the study design and gathering of data. MCC, AN, and AB contributed to the analysis of data and preparation of the manuscript. MCC and LB conducted the statistical analysis. All the authors participated in revision of the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

- Beard D J, Harris K, Dawson J, Doll H, Murray D W, Carr A J, Price J P. Meaningful changes for the Oxford hip and knee scores after joint replacement surgery. J Clin Epidemiol 2015; 68(1): 73–9.

- Beaton D E, Boers M, Wells G A. Many faces of the minimal clinically important difference (MCID): a literature review and directions for future research. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2002; 14(2): 109–14.

- Becker B J. Synthesizing standardized mean-change measures. Br J Math Stat Psychol 1988; 41(2): 257–78.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences: Academic Press, New York; 1978.

- Copay A G, Subach B R, Glassman S D, Polly D W, Jr., Schuler T C. Understanding the minimum clinically important difference: a review of concepts and methods. Spine J 2007; 7(5): 541–6.

- Coster M, Karlsson M K, Nilsson J A, Carlsson A. Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of a Self-reported Foot and Ankle Score (SEFAS). Acta Orthop 2012; 83(2): 197–203.

- Coster M C, Bremander A, Rosengren B E, Magnusson H, Carlsson A, Karlsson M K. Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of the Self-reported Foot and Ankle Score (SEFAS) in forefoot, hindfoot, and ankle disorders. Acta Orthop 2014a; 85(2): 187–94.

- Coster M C, Rosengren B E, Bremander A, Brudin L, Karlsson M K. Comparison of the Self-Reported Foot and Ankle Score (SEFAS) and the American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society Score (AOFAS). Foot Ankle Int 2014b; 35(10): 1031–6.

- Coster M C, Rosengren B E, Bremander A, Karlsson M K. Surgery for adult acquired flatfoot due to posterior tibial tendon dysfunction reduces pain, improves function and health related quality of life. Foot Ankle Surg 2015; 21(4): 286–9.

- Dahlberg G. Statistical methods for medical and biological students. 2 ed. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd; 1940.

- Dawson J, Boller I, Doll H, Lavis G, Sharp R, Cooke P, et al. Minimally important change was estimated for the Manchester-Oxford Foot Questionnaire after foot/ankle surgery. J Clin Epidemiol 2014; 67(6): 697–705.

- de Vet H C, Terluin B, Knol D L, Roorda LD, Mokkink L B, Ostelo R W, Hendriks E J M, Bouter L M, Terwee C B. Three ways to quantify uncertainty in individually applied “minimally important change” values. J Clin Epidemiol 2010; 63(1): 37–45.

- Hagg O, Fritzell P, Nordwall A, Swedish Lumbar Spine Study G. The clinical importance of changes in outcome scores after treatment for chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J 2003; 12(1): 12–20.

- Hosman A H, Mason R B, Hobbs T, Rothwell A G. A New Zealand national joint registry review of 202 total ankle replacements followed for up to 6 years. Acta Orthop 2007; 78(5): 584–91.

- Mokkink L B, Terwee C B, Knol D L, Stratford P W, Alonso J, Patrick D L, et al. The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: a clarification of its content. BMC medical research methodology 2010a; 10: 22.

- Mokkink L B, Terwee C B, Patrick D L, Alonso J, Stratford P W, Knol D L, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res 2010b; 19(4):539–49.

- Mokkink L B, Prinsen C A, Bouter L M, Vet H C, Terwee C B. The Consensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) and how to select an outcome measurement instrument. Braz J Phys Ther 2016; 20(2): 105–13.

- Muradin I, van der Heide H J L. The foot function index is more sensitive to change than the Leeds Foot Impact Scale for evaluating rheumatoid arthritis patients after forefoot or hindfoot reconstruction. Int Orthop (SICOT) 2016; 40: 745–9.

- Rolfson O, Bohm E, Franklin P, Lyman S, Denissen G, Dawson J, Dunn J, Eresian Chenok K, Dunbar M, Overgaard S, Garellick G, Lübbeke A. Patient-reported outcome measures in arthroplasty registries Report of the Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Working Group of the International Society of Arthroplasty Registries Part II. Recommendations for selection, administration, and analysis. Acta Orthop 2016; 87eSuppl363: 9–23.

- Sierevelt I N, van Eekeren I C, Haverkamp D, Reilingh M L, Terwee C B, Kerkhoffs G M. Evaluation of the Dutch version of the Foot and Ankle Outcome Score (FAOS): responsiveness and Minimally Important Change. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2016; 24(4): 1339–47.

- Sorensen A A, Howard D, Tan W H, Ketchersid J, Calfee R P. Minimal clinically important differences of 3 patient-rated outcomes instruments. J Hand Surg Am 2013; 38(4): 641–9.

- Suk M. Musculoskeletal Outcomes measures and Instruments: AO Foundation; 2009.

- Terluin B, Eekhout I, Terwee C B, de Vet H C. Minimal important change (MIC) based on a predictive modeling approach was more precise than MIC based on ROC analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2015; 68(12): 1388–96.

- Terwee C B, Bot S D, de Boer M R, van der Windt D A, Knol D L, Dekker J, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 2007; 60(1): 34–42.

- van Kampen D A, Willems W J, van Beers L W A H, Castelein R M, Scholtes V A B, Terwee C B. Determination and comparison of the smallest detectable changes (SCD) and the minimal important change (MIC) of four-shoulder patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). J Orth Surg Res 2013; 8: 40.

- Wyrwich KW, Norquist JM, Lenderking WR, Acaster S, Industry Advisory Committee of International Society for Quality of Life R. Methods for interpreting change over time in patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res 2013; 22(3): 475–83.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2006; 4:79.