Abstract

Background and purpose — Hexapod ring fixators such as the Taylor Spatial Frame (TSF) have shown good outcomes. However, there have only been a few studies comparing the use of TSF with various etiologies of the deformity. We compared the use of TSF in congenital and acquired deformities in children.

Patients and methods — We reviewed 213 lower extremity reconstructive procedures with the TSF in 192 patients who were operated between October 2000 and October 2015. 128 procedures (67 proximal tibiae, 51 distal femora, and 10 distal tibiae) in 117 children (median age 14 (4–18) years; 59 girls) fulfilled the inclusion criteria. 89 procedures were done in children with congenital deformities (group C) and 39 were done in children with acquired deformities (group A). Outcome parameters were lengthening and alignment achieved, lengthening index, complications, and analysis of residual deformity in a subgroup of patients.

Results — Mean lengthening achieved was 3.9 (1.0–7.0) cm in group C and 3.7 (1.0–8.0) cm in group A (p = 0.5). Deformity parameters were corrected to satisfaction in all but 3 patients, who needed further surgery for complete deformity correction. However, minor residual deformity was common in one-third of the patients. The mean lengthening index was 2.2 (0.8–10) months/cm in group C and 2.0 (0.8–6) months/cm in group A (p = 0.7). Isolated analysis of all tibial and femoral lengthenings showed similar lengthening indices between groups. Complication rates and the need for secondary surgery were much greater in the group with congenital deformities.

Interpretation — The TSF is an excellent tool for the correction of complex deformities in children. There were similar lengthening indices in the 2 groups. However, congenital deformities showed a high rate of complications, and should therefore be addressed with care.

Current methods of limb lengthening are based on gradual distraction osteogenesis as introduced by Gavril Ilizarov (De Bastiani et al. Citation1987, Paley Citation1988, Ilizarov Citation1989a, Citationb). The use of Ilizarov external fixators for lengthening and axis correction requires mechanical hinges and translation mechanisms to build a custom-made frame for each patient (Ilizarov Citation1989a, Citationb). The construction of the frame might be demanding in complex deformities, frequently requiring changes of the frame construction during the course of lengthening. The development of hexapod fixators allows simultaneous correction of multiplanar complex deformities (Taylor Citation2016). Further progress in the field of limb lengthening has been made by the development of mechanical (Guichet Citation1999, Cole et al. Citation2001) and motorized intramedullary lengthening devices (Baumgart et al. Citation1997, Rozbruch et al. Citation2014, Paley Citation2015).

For limb lengthening procedures and complex deformity corrections in children with open growth plates and a substantial amount of growth potential remaining, the use of external fixator devices for correction is still indicated. The insertion of current intramedullary lengthening devices would harm the growth plates in skeletally immature patients. Furthermore, the severity of a deformity may limit the use of intramedullary lengthening devices (Horn et al. Citation2015, Küçükkaya et al. Citation2015).

External fixation permits gradual correction of multiplanar long bone deformities with minimal soft tissue trauma and a minimal risk of neurovascular injury. Various types of external fixators are available for this purpose, whereas hexapod ring fixators such as the Taylor Spatial Frame (TSF) have shown good outcomes and several advantages over the classical Ilizarov apparatus or monolateral fixators, especially in the treatment of complex multiplanar deformities (Rodl et al. Citation2003, Fadel and Hosny Citation2005, Eidelman et al. Citation2006, Manner et al. Citation2007, Dammerer et al. Citation2011, Tsibidakis et al. Citation2014).

The TSF is a circular external fixator where the rings are connected by 6 oblique telescopic struts, creating a hexapod. By varying the strut lengths, the relative orientation of the rings and bone segments is changed and allows simultaneous six-axis correction (Taylor Citation2016). An internet-based software program is used to generate a schedule for adjustment of each strut, to obtain the desired correction. The mathematical concept behind the software program—which allows definition of radiograph projections in mathematical terms—is based on the principle of projective geometry (Kline Citation1955, Taylor Citation2002). There have been few reports in the literature about the use of TSF in children. We therefore present our results on the use of TSF in congenital and acquired deformities in children.

Patients and methods

We reviewed 213 lower extremity reconstructive procedures (lengthening, deformity correction, or both) with the Taylor Spatial Frame (TSF; Smith and Nephew, Memphis, TN) in 192 patients who were operated between October 2000 and October 2015. The inclusion criteria for this retrospective study were: gradual deformity corrections with the TSF, age ≤18 years, and follow-up of at least 6 months after frame removal. Patients with acute corrections with the TSF, bifocal lengthenings, or fracture or pseudarthrosis treatment with the TSF were excluded from the study. 128 procedures/frames (67 proximal tibiae, 51 distal femora, and 10 distal tibiae) in 117 children (median age 14 (4–18) years; 59 girls) fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Mean follow-up after frame removal was 32 (6–68) months. 89 TSFs (in 81 children; 54 femora and 35 tibiae) were applied for congenital deformities (group C) and 39 TSFs (in 36 children; 20 femora and 19 tibiae) were applied for acquired deformities (group A). The most common diagnoses were congenital femoral deficiency, fibular hemimelia, hypoplasia/idiopathic leg length discrepancy, and sequelae after physeal injury or fracture ().

Table 1. Diagnoses in all 128 procedures included in the study

6 procedures were performed to correct axial deformities with only minor lengthening and 19 procedures involved pure lengthening without any axial correction. 57 frames were used to correct biplanar deformities and 46 frames were used to correct triplanar deformities, all including lengthening. Mean lengthening for all frames was 38 (7–80) mm. Other deformity parameters were valgus 11° (5–35), varus 16° (5–35), procurvatum 12° (5–25), and external rotation 17° (10–40). Clinical and radiographic evaluations of all deformity parameters were done before and after surgery. For this purpose, long standing radiographs in the anterior-posterior view and ordinary radiographs in the anterior-posterior and lateral views of the affected segment were obtained from all patients. Furthermore, long standing lateral views were obtained when there were clinical signs of deformity in the sagittal plane. If rotational malalignment was present clinically, CT-scans were used to measure the rotational profile of the femur and the tibia. Deformity analysis was done based on the malalignment test and the malorientation test described by Paley (Citation2005).

The TSF is applied by use of 3 optional basic methods available in the software program: "chronic deformity", "rings first method", and "total residual deformity" (Taylor Citation2002). In our patients, the chronic deformity strategy was used whereby frames with specific strut lengths were built preoperatively according to the deformity parameters entered, limb size, and the planned mounting parameters. Where there was residual deformity at the end of lengthening, the "total residual" mode was used for further and final correction.

After the frame was mounted on the femur or tibia, an osteotomy was performed by the drilling and osteotome technique. Lengthening of 1 mm/day was initiated 7 days after surgery. The TSF lengthening struts do not allow lengthening increments of 0.25 mm, but only 1 mm. For this reason, lengthening was performed by not adjusting all the struts at the same time, but by doing adjustments of 2 struts at a time at 3 times during the day. Full weight bearing was permitted at any time during treatment with the TSF.

Patients were followed at an interval of 1–2 weeks during lengthening and every sixth week during the consolidation phase.

Radiographic consolidation of the regenerate was assumed when at least 3 of 4 cortices showed sufficient bone formation on anterior-posterior and lateral radiographs. Consolidation time was defined as the time from the osteotomy to radiographic consolidation. At the endpoint "radiographic consolidation", the frame was removed and a walking cast was applied for 6 weeks. Lengthening index was defined as the time from the osteotomy to radiographic consolidation divided by the lengthening distance achieved, in centimeters.

Outcome parameters were as follows: lengthening and alignment achieved, lengthening index, complications, and residual deformity in a subgroup of patients. Lengthening and alignment achieved were measured on long standing radiographs when the prescription schedule for strut adjustments was completed, including eventual "total residual" schedules (). Residual deformity was defined as persistent deformity after frame removal. It was analyzed in a subgroup of patients (n = 46) who had available long standing radiographs after frame removal and who either had reached skeletal maturity when the procedure was performed, or did not have an underlying pathology that could lead to recurrence of the deformity after frame removal. Complications were graded into problems, obstacles, and sequelae according to Paley (Citation1990).

Figure 1. A 14-year-old boy with shortening and valgus deformity after physeal injury at the left distal femoral physis. Long standing radiograph initially (panel A), when the lengthening and axis correction were completed (B), and 12 months after frame removal (C).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed based on Student’s t-test (t-test for equality of means) with one observation per patient and with equal variances assumed (IBM SPSS software version 21). Any p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Lengthening and alignment achieved

Mean age at lengthening was 12.2 (4–18) years in group C and 14.0 (5–18) years in group A (p = 0.02) (). The mean lengthening achieved in group C was 3.9 (1.0–7.0) cm and it was 3.7 (1.0–8.0) cm in group A (p = 0.5). Mean time in the frame was 7.6 (3.9–25.8) months in group C and 6.2 (3.3–11.2) months in group A (p = 0.01).

Table 2. Results for Group C (congenital deformities) and Group A (acquired deformities). Values are mean (range)

In 25 procedures, 1 or 2 additional "total residual" adjustments were necessary for full correction of the deformities. Deformity parameters measured at completion of the lengthening protocol were corrected to satisfaction in all but 3 patients. Criteria for satifaction were mechanical axis through the middle of the knee or within zone 1 (Stevens et al. Citation1999), and less than 1 cm of shortening in the lengthened segment. In 3 patients, the lengthening process had to be stopped before completion due to either pain or contracture. Furthermore, 2 patients needed additional surgery short time after frame removal due to recurrent deformity. In all other patients, no losses of length or axis correction were observed during further follow-up.

Lengthening index

Mean lengthening index was 2.2 (0.8–10) months/cm in group C and 2.0 (0.8–6) months/cm in group A (p = 0.7). Isolated analysis of all tibial lengthenings in both groups showed a mean lengthening index of 2.6 (0.8–10) months/cm in group C and 2.4 (1.0–6.0) months/cm in group A. Femoral lengthening showed a mean lengthening index of 1.6 (0.8–4.0) months/cm for group C and 1.7 (0.8–4.4) months/cm for group A. There were no statistically significant differences in lengthening index between groups for either tibial or femoral lengthening (p = 0.6 and p = 0.8, respectively).

Complications

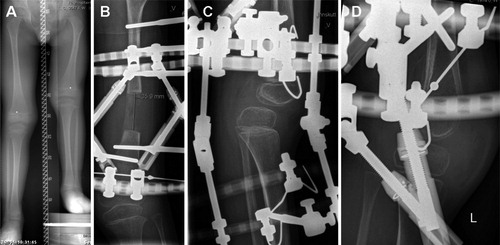

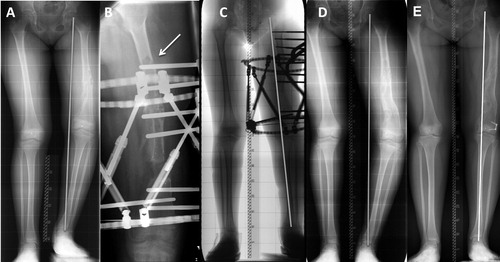

In group C, 9 patients (all with tibial lengthening) received autologous bone grafting harvested from the iliac crest to provide consolidation (). All 9 patients healed with 1 bone grafting procedure after a mean interval of 6 (3–12) months after the grafting procedure. 3 patients sustained a fracture during treatment and were operated with extension of the frame, while 5 patients fractured in the callotasis zone after frame removal (all group C: 4 femora and 4 tibiae). In 1 patient in group C (age 6, congenital femoral deficiency, femoral lengthening), the knee subluxated during lengthening despite bridging of the knee with a hinged extension of the frame (). This problem could be solved by placing TSF struts between the 2 rings across the knee for gradual reduction, instead of hinges. 1 patient in group C developed osteomyelitis in the femur 2 years after frame removal. The infection could be treated by surgical drainage and antibiotic treatment. 1 patient in group C with Ollier’s disease developed complete recurrence of femoral varus deformity within 1 year of frame removal (). This obstacle could be addressed by hemi-epiphysiodesis. In 1 patient in group C, surgical decompression of the nervus peroneus communis and profundus had to be performed.

Figure 2. A 6-year-old boy with congenital femoral deficiency and fibular hemimelia (panel A). After 3.5 cm of lengthening, subluxation of the knee was observed, although the knee was transfixated by a hinged frame (B and C). Hinges were replaced by TSF struts and the knee was gradually reduced to anatomical position (D). As a sequela, the patient suffers from reduced range of motion in the knee. At the latest follow-up, range of motion was from −5° extension to 50° of flexion with slow but continuous improvement.

Figure 3. An 8-year-old girl with Ollier’s disease. The initial deformity included shortening and varus (panel A). The patient sustained a fracture during treatment (B) and was treated by extension of the frame. The other long standing radiographs were taken when lengthening was completed (C), after frame removal—with complete recurrence of varus deformity (D), and when this was solved by hemi-epiphysiodesis, with an acceptable result (E).

Table 3. Problems, obstacles, and complications in boths groups

In group A, 2 patients had to be operated for possible compartment syndrome based on symptoms and clinical findings in the first days postoperatively. Pressure in the compartments had not been measured before surgery. In 1 of these patients, fasciotomy was performed and no muscle necrosis was found. In the second patient, the compartment syndrome could be confirmed intraoperatively. Muscle necrosis in the anterior compartment was found. All necrotic muscle from this compartment had to be removed, which resulted in a foot drop, which was later addressed by transposition of the posterior tibial tendon. In this patient, the compartment syndrome did not become evident until day 3 after surgery. For postoperative pain management, the patient had received a continuous peripheral regional anesthesia of the sciatic nerve for 3 days. 1 patient developed non-septic arthritis in the knee after 2 femoral lengthenings (with a total lengthening of 14 cm). No fractures or other major complications were observed in group A. Minor complications such as superficial pin-tract infections were observed in both groups.

Residual deformity

46 deformity corrections (in 39 patients) fulfilled the criteria for analysis for the presence of possible residual deformities, which were analyzed on long standing radiographs at follow-up after frame removal. 12 patients (about one-third of all the patients analyzed) showed minor residual deformity: 8 patients with a varus deformity of 3–5° and 4 patients with a valgus deformity of 2–5°. Among these, 2 patients had an additional shortening of ≥1 cm (10 mm and 14 mm).

Discussion

The present study has shown that the TSF is a reliable tool for the correction of complex deformities in children, with a high degree of accuracy in deformity correction and lengthening. This confirms the findings of other authors (Eidelman et al. Citation2006, Manner et al. Citation2007, Blondel et al. Citation2009). The "total residual" mode of the TSF software is a powerful aspect of the system, allowing the surgeon to perform an unlimited number of corrections in order to obtain a good final result of correction (Paloski et al. Citation2012). The fact that some patients may develop contractures during lengthening makes it difficult to obtain reliable long standing radiographs with the frame mounted in some cases, and residual deformity may not be detected before frame removal. Furthermore, skeletally immature patients with congenital deformities had to be excluded from residual deformity analysis since the underlying pathology of growth in these patients would lead to recurrent deformity within short periods of time. A thorough deformity analysis is essential before treatment is initiated. We preferred to analyze final residual deformity in a subgroup of patients, on long standing radiographs after frame removal, and we found only minor residual deformities in our patients.

We defined lengthening index as the number of months that the external fixator was mounted on the patient’s limb divided by the centimeters of lengthening, which gave us an estimate of the efficiency of the lengthening treatment. The mean lengthening indices were 2.2 (0.8–10) months/cm in group C and 2.0 (0.8–6.0) months/cm in group A. In our retrospective investigation, children with congenital deformities showed a similar lengthening index—both in tibial and femoral lengthening—compared to children with acquired deformities. Although no statistically significant difference was found between the lengthening indices in group C and group A, there was a small difference in mean values, showing slightly better healing in group A regarding tibial lengthening. This finding may be of some importance, since all the cases of delayed healing occurred in tibial cases in group C, indicating better healing after tibial lengthening in acquired deformities than in congenital deformities.

The mean age in the group with congenital deformities was lower, which may have influenced lengthening indices in a positive way in the congenital group. Several reports have described lengthening indices for lengthening with the TSF, and those in our investigation are comparable to those published by other authors. Iobst (Citation2010) reported a lengthening of 1.79 months/cm, Nakase et al. (2005) reported an index of 1.45 months/cm in patients who underwent at least 2 cm of lengthening, and Marangoz et al. (Citation2008) reported an index of 2.2 months/cm in 8 femoral lengthenings.

Children in the congenital group had much higher rates of secondary surgery and complications. Autologous bone grafting was required after tibial lengthening in 9 of the 81 patients in group C, whereas the regenerate in all patients in group A consolidated without further interventions. Prolonged healing time of the regenerate after lengthening remains a problem, especially in patients with congenital conditions. Adjuvant drug therapies to enhance healing should be considered and may be used in the future, based on evidence from clinical studies and animal experiments (Sabharwal Citation2011, Sailhan Citation2011).

All fractures happened in group C, either during treatment with the frame or after frame removal. All patients followed the protocol with 6 weeks in a walking cast after frame removal. Our results confirm the findings of other authors, showing a higher risk of additional surgery in tibial lengthening and a generally higher risk of complications such as fracture after frame removal in correction of congenital deformities (Velazquez et al. Citation1993, Aston et al. Citation2009, Launay et al. Citation2013, Tsibidakis et al. Citation2014). In a study by Abdelgawad et al. (Citation2015), prophylactic rodding significantly reduced the incidence of femoral fracture after lengthening in congenital femoral deficiency and should be considered as an option to reduce the rate of fractures. It appears that the use of a walking cast for a certain period after frame removal is inadequate in at least some patients, depending on the underlying diagnosis.

In the group with acquired deformities, 2 patients were operated for suspected compartment syndrome in the lower leg, whereas muscle necrosis in the anterior compartment was found in 1 of these patients. Both patients had received regional anesthesia for postoperative pain management, which may delay the diagnosis of compartment syndrome (Mar et al. Citation2009, Wu et al. Citation2011). Since these incidents, no regional anesthesia has been used in tibial osteotomies—either in children or in adults—at our department.

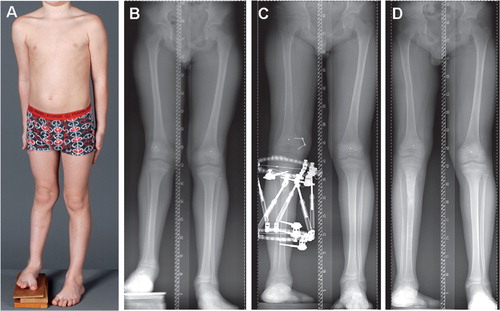

Interestingly, similar lengthening indices were found in the 2 groups, but there was a high rate of fracture after lengthening in the group with congenital deformities. This might indicate that the bone regenerate in congenital deformities did not have the same mechanical strength as the regenerate in acquired deformities. Congenital deformities in children should be addressed with a careful approach, probably combining lengthening with a guided growth procedure in order to reduce the number of lengthening procedures required and to avoid complications ().

Figure 4. An 11-year-old boy with congenital femoral deficiency and fibular hemimelia (A). Long standing radiographs showed shortening in the femur and tibia, and valgus deformity caused by a dysplastic lateral femoral condyle (B). Since most of the shortening was below the knee, we started reconstruction by lengthening of the tibia and hemi-epiphysiodesis of the femur (C). Panel D was taken 6 months after frame removal. Femoral lengthening will be necessary in the future.

To our knowledge, our study is 1 of only 2 investigations that have directly compared the use of the TSF in congenital and acquired deformities. In a study by Tsibidakis et al. (Citation2014), the etiology of the deformity had no influence on the incidence of complications in 66 children (89 tibiae) treated with the TSF. These results could not be confirmed in our study, since the rate of complications was much higher in the congenital group.

The number of children and procedures that we included was quite high, allowing us to compare different patient groups in terms of, for example, lengthening index and complications—which was a strength of the study. However, a weakness was that the data were collected retrospectively.

In conclusion, the TSF is an excellent tool for the correction of complex deformities in children. The "total residual" modus allows precise correction of residual deformities. Children with congenital deformities showed a similar lengthening index to that in children with acquired deformities. However, the rates of secondary surgeries and complications were much higher in children with congenital deformities. 2 major concerns with lengthening in children with congenital deformities are the lack of healing of the regenerate and fractures after frame removal. Any effort to promote healing of the regenerate would therefore be worthwhile. Furthermore, some kind of support for the regenerate after frame removal—either by intramedullary rodding, a temporary plaster cast, or an orthosis—should be considered.

JH, SH, IH, and HS performed the operations and examined patients at follow-up. JH and RBG performed the radiological measurements. JH wrote the manuscript and performed the statistical analysis. HS, IH, SH, and RBG revised and approved the manuscript.

Leif Pål Kristiansen is acknowledged for having operated on many patients included in this paper.

No competing interests declared.

- Abdelgawad A A, Jauregui J J, Standard S C, Paley D, Herzenberg J E. Prophylactic intramedullary rodding following femoral lengthening in congenital deficiency of the femur. J Pediatr Orthop 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

- Aston W J, Calder P R, Baker D, Hartley J, Hill R A. Lengthening of the congenital short femur using the Ilizarov technique: a single-surgeon series. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009; 91: 962–7.

- Baumgart R, Betz A, Schweiberer L. A fully implantable motorized intramedullary nail for limb lengthening and bone transport. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1997; (343): 135–43

- Blondel B, Launay F, Glard Y, Jacopin S, Jouve J L, Bollini G. [Limb lengthening and deformity correction in children using hexapodal external fixation: Preliminary results for 36 cases.]. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2009; 95: 525–30.

- Cole J D, Justin D, Kasparis T, De Vlught D, Knobloch C. The intramedullary skeletal kinetic distractor (ISKD): first clinical results of a new intramedullary nail for lengthening of the femur and tibia. Injury 2001; (32 Suppl 4): SD129–39.

- Dammerer D, Kirschbichler K, Donnan L, Kaufmann G, Krismer M, Biedermann R. Clinical value of the Taylor Spatial Frame: a comparison with the Ilizarov and Orthofix fixators. J Child Orthop 2011; 5: 343–9.

- De Bastiani G, Aldegheri R, Renzi-Brivio L, Trivella G. Limb lengthening by callus distraction (callotasis). J Pediatr Orthop 1987; 7: 129–34.

- Eidelman M, Bialik V, Katzman A. Correction of deformities in children using the Taylor spatial frame. J Pediatr Orthop B 2006; 15: 387–95.

- Fadel M, Hosny G. The Taylor spatial frame for deformity correction in the lower limbs. Int Orthop 2005; 29: 125–9.

- Guichet J M. Leg lengthening and correction of deformity using femoral Albizzia nail. Orthopäde 1999; (28): 1066–77.

- Horn J, Grimsrud Ø, Dagsgard AH, Huhnstock S, Steen H. Femoral lengthening with a motorized intramedullary nail - a matched-pair comparison with external ring fixator lengthening in 30 cases. Acta Orthop 2015; 86(2): 248–56.

- Ilizarov G A. The tension-stress effect on the genesis and growth of tissues. Part I. The influence of stability of fixation and soft-tissue preservation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989a; (238): 249–281.

- Ilizarov G A. The tension-stress effect on the genesis and growth of tissues: Part II. The influence of the rate and frequency of distraction. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989b; (239): 263–85.

- Iobst C. Limb lengthening combined with deformity correction in children with the Taylor Spatial Frame. J Pediatric.Orthop B 2010; 19: 529–34.

- Kline M. Projective Geometry. The Sciences. 1955;January 1.

- Küçükkaya M, Karakoyun Ö, Sökücü S, Soydan R. Femoral lengthening and deformity correction using the Fitbone motorized lengthening nail. J Orthop Sci 2015; 20(1): 149–54.

- Launay F, Younsi R, Pithioux M, Chabrand P, Bollini G, Jouve J L. Fracture following lower limb lengthening in children: a series of 58 patients. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2013; 99: 72–9.

- Manner H M, Huebl M, Radler C, Ganger R, Petje G, Grill F. Accuracy of complex lower-limb deformity correction with external fixation: a comparison of the Taylor Spatial Frame with the Ilizarov ring fixator. J Child Orthop 2007; 1: 55–61.

- Mar G J, Barrington M J, McGuirk B R. Acute compartment syndrome of the lower limb and the effect of postoperative analgesia on diagnosis. Br J Anaesth 2009; 102(1): 3–11.

- Marangoz S, Feldman DS, Sala DA, Hyman JE, Vitale MG. Femoral deformity correction in children and young adults using Taylor Spatial Frame. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466(12): 3018–24.

- Nakase T, Kitano M, Kawai H, Ueda T, Higuchi C, Hamada M, Yoshikawa H. Distraction osteogenesis for correction of three-dimensional deformities with shortening of lower limbs by Taylor Spatial Frame. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2009; 129(9): 1197–201.

- Paley D. Current techniques of limb lengthening. J Pediatr Orthop 1988; 8: 73–92.

- Paley D. Problems, obstacles, and complications of limb lengthening by the Ilizarov technique. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1990; (250): 81–104.

- Paley D. Principles of Deformity Correction. Berlin Heidelberg New York: Springer; 2005.

- Paley D. PRECICE intramedullary limb lengthening system. Expert Rev Med Devices 2015; 12(3): 231–49.

- Paloski M, Taylor BC, Iobst C, Pugh KJ. Pediatric and adolescent applications of the Taylor Spatial Frame. Orthopedics. 2012;35:518–527.

- Rodl R, Leidinger B, Bohm A, Winkelmann W. [Correction of deformities with conventional and hexapod frames–comparison of methods]. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb 2003; 141: 92–8.

- Rozbruch SR, Birch JG, Dahl MT, Herzenberg JE. Motorized intramedullary nail for management of limb-length discrepancy and deformity. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2014; 22(7): 403–9.

- Sabharwal S. Enhancement of bone formation during distraction osteogenesis: pediatric applications. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2011; 19: 101–11

- Sailhan F. Bone lengthening (distraction osteogenesis): a literature review. Osteoporos Int 2011; 22: 2011–5.

- Stevens P, Maguire M, Dales M D, Robins A J. Physeal stapling for idiopathic genu valgum. J. Pediatr Orthop 1999; 19(5): 645–9.

- Taylor J C. Six-axis deformity analysis and correction. In: (Paley D, ed.) Principles of Deformity Correction. Berlin Heidelberg New York: Springer; 2002 pp: 411–36.

- Taylor J C. Correction of general deformity with Taylor Spatial Frame. www.jcharlestaylor.com, Accessed April 2016.

- Tsibidakis H, Kanellopoulos A D, Sakellariou V I, Soultanis K C, Zoubos A B, Soucacos P N. The role of Taylor Spatial Frame for the treatment of acquired and congenital tibial deformities in children. Acta Orthop Belg 2014; 80: 419–25.

- Velazquez R J, Bell D F, Armstrong P F, Babyn P, Tibshirani R. Complications of use of the Ilizarov technique in the correction of limb deformities in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993; 75: 1148–56.

- Wu J J, Lollo L, Grabinsky A. Regional anesthesia in trauma medicine. Anesthesiol Res Pract 2011; 2011: 713281.