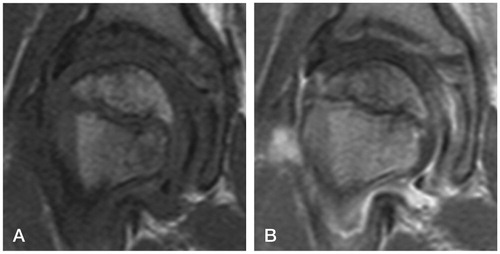

A boy aged 9 years and 4 months developed a recurrent right-sided limp. His father, a radiologist, prompted a contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) after 6 weeks and diagnosed early Perthes’ disease ().

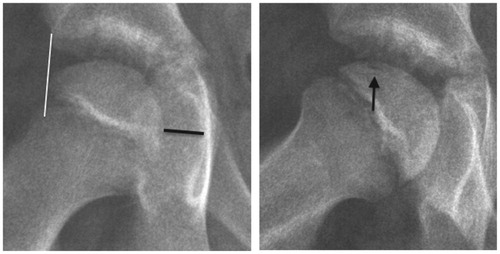

There were risk factors for a poor prognosis. The boy was relatively old for Perthes’ disease. He was a physically active child of small stature with uncertain compliance for non-weight bearing. Disseminated epiphyseal signal alterations in MRI suggested total involvement, Catterall group 4 (Catterall Citation1971). 2 weeks later, a posteromedial epiphyseal-metaphyseal cyst was seen. At a new examination another 2 weeks later, radiographs and MR images showed a subchondral fracture, but the epiphysis was not sclerotic (). The disease was in early stage Ia according to the modified Waldenström classification (Joseph et al. Citation2003, Hyman et al. Citation2015).

Owing to the risk of a severe course, we suggested early containment surgery. The family, however, opted for a mainly conservative treatment with close follow-up by MRI.

Thus, treatment consisted of minimal weight bearing by use of crutches or a wheelchair.

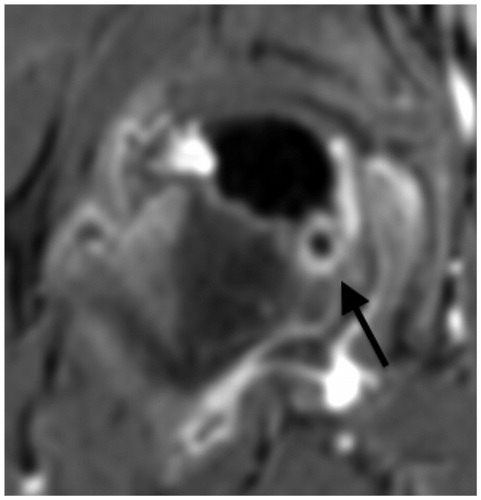

At 5 months after onset, there was still no sclerosis or significant extrusion in radiographs. However, a slight reduction in epiphyseal height and some anterior flattening indicated stage Ib. The subchondral fracture now involved slightly more than 50% of the epiphysis. A simultaneous contrast MRI showed complete lack of perfusion in the center, a small area of hyperperfusion laterally, persistence of the epiphyseal-metaphyseal cyst posteromedially, and marked synovitis (), all suggesting a worsening hip. The family decided to resort to anti-resorptive treatment. A dose of 60 mg denosumab was administered.

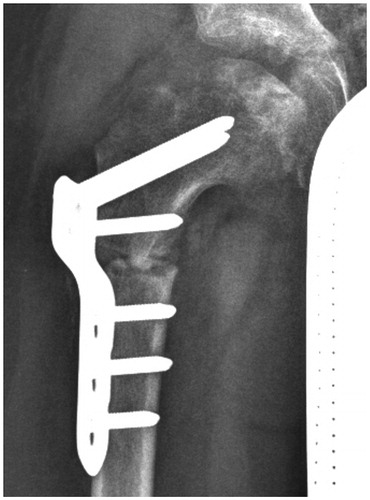

At 11.5 months, an MRI showed stage IIb with signs of beginning of loss of containment (Meiss Citation2001) (). We strongly advised surgery. Further application of denosumab was not considered. 1 year after onset and 7 months after the denosumab injection, radiographs showed atypical re-ossification with a centrolateral density (stage IIIa), moderate extrusion, a faint, radiolucent metaphyseal band, and major anterior flattening (). 1 month later, a varus osteotomy of the proximal femur was performed. 6 weeks postoperatively, the contour of the head was uneven and the bone texture irregular, possibly attributable to the denosumab therapy ().

Figure 5. At 1 year. Moderate extrusion. Anterior flattening. Stage IIIa.

A proximal varus osteotomy was performed 1 month later.

Radiographs 6 months postoperatively revealed consolidation of the osteotomy; 1 month later, the plate was removed.

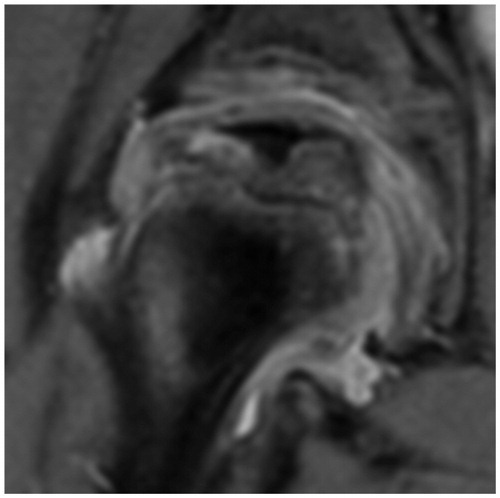

2 years after onset, MRI showed an enlarged, slightly ovoid, well-contained head with advanced re-ossification (stage IIIb) ().

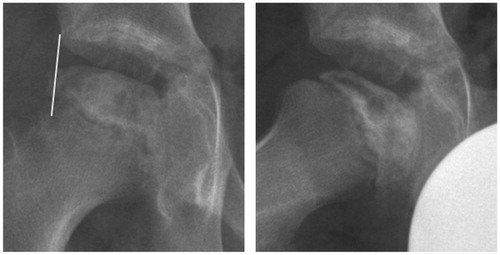

The last MRI, performed 2 years and 8 months after onset, showed healing with about 90% re-ossification (almost stage IV). The head was almost spherical (, see Suspplementary data). There was an 11% increase in the maximum diameter (). Under the assumption of bilateral sphericity, the volume was 60 cm3 on the right side and 44 cm3 on the left side. The difference would mean an increase in volume of 36%.

In the final assessment, the boy could comfortably carry out his daily activities and sports. He had normal hip motion and no pain or limp.

The boy’s parents consented to data from the case being published.

Discussion

In principle, Perthes’ disease is self-healing, and the optimal outcome is a normal hip (Stulberg et al. Citation1981). However, deformation during the course of the disease leads to a high risk of later osteoarthritis.

Treatment of Perthes’ disease varies between supervised neglect, strict non-weight bearing, and surgery. The cause of the disease still being unknown there is no cause-focused therapy. In his recent review, Kim (Citation2012) reported that increased bone resorption and delayed new bone formation, in combination with continued mechanical loading of the hip, contribute to the femoral head deformity. Thus, biological treatment appears possible.

Suppression of osteoclastic activity using intravenous biphosphonate in experimentally induced femoral head necrosis in piglets seemed to prevent total head collapse (Kim et al. Citation2005). This approach was further analyzed in clinical trials—with variable results (Agarwala et al. Citation2005, Young et al. Citation2012, Lee et al. Citation2015). Treatment with bisphosphonates has limitations, especially in children. Bisphosphonates accumulate in bone and may remain incorporated for years. Animal studies have shown that bisphosphonates can cause impairment of long bone growth (Lepola et al. Citation1996, Camacho et al. Citation2001, Kim et al. Citation2005).

As for denosumab, a human monoclonal antibody to RANKL that also acts as an inhibitor of osteoclasts, no growth retardation has been noted in animal or clinical studies (Kim et al. Citation2006, Wang et al. Citation2014, Kobayashi and Setsu Citation2015). Denosumab has the advantage of not binding to bone. Denosumab treatment rapidly reduces bone turnover, reaching a nadir by 3 days. Return of turnover to pretreatment level generally occurs within 9 months. Caution should be exercised regarding the off-label use in children because of the risk of initial severe hypocalcemia. The blood level of vitamin D should be kept in the high normal range, and sufficient intake of calcium is needed (Grasemann et al. Citation2013, Hoyer-Kuhn et al. Citation2016)—recommendations that we respected. On the other hand, there is a risk of rebound hypercalcemia. The latter is caused by a washout of calcium after discontinuation of the drug and can result in renal dysfunction. Close monitoring and treatment is essential (Wang et al. Citation2014, Setsu et al. Citation2016).

Denosumab could probably interfere with fracture healing. In an animal model, a delay in callus remodeling was noted, but also an increase in callus strength and stiffness (Gerstenfeld et al. Citation2009). Because no major negative clinical effects have been shown to date, osteoporosis therapy with denosumab is not interrupted if a fracture occurs (Adami et al. Citation2012). However, some recent reports on atypical femoral fractures in patients receiving denosumab underscore the need for future epidemiological studies (Aspenberg Citation2014, Schilcher and Aspenberg Citation2014).

With these precautions in mind, Hoyer-Kuhn et al. (Citation2016) used denosumab in a group of children suffering from severe osteogenesis imperfecta and showed that the subcutaneous application of 1 mg per kg body weight every 12 weeks was efficient and safe. In our case, a single dose of 1.94 mg per kg body weight was administered.

There is increasing experience with the use of denosumab in severe disorders in childhood such as aneurysmal bone cyst, juvenile Paget’s disease, giant cell tumor of bone, fibrous dysplasia, and osteogenesis imperfecta (Lange et al. Citation2013, Grasemann et al. Citation2013, Kobayashi and Setsu Citation2015, Wang et al. Citation2014, Hoyer-Kuhn et al. Citation2016).

In our case, evaluation of the early response to the drug was difficult. As there was no rapid improvement in joint morphology, we recommended surgery. With earlier administration of denosumab, surgery might perhaps have been avoided.

In retrospect, the effect of the drug resembles the effect of an osteoplasty. Wang et al. noted that denosumab treatment in a child with fibrous dysplasia led to retention of primary spongiosa of the growth plate of the distal tibia. We hypothesize that this phenomenon is ubiquitous, and occurs also at the circumferential growth zone of the proximal femoral epiphysis (Kim et al. Citation2012, p 663). Hence, denosumab might have led to preservation of epiphyseal trabeculae with osteogenic capacity.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of treatment of Perthes’ disease with denosumab in combination with a varus osteotomy and close follow-up by MRI and radiographs. It is our impression that denosumab had a positive effect on the outcome. It is very unlikely that the good result can be attributed solely to the varus osteotomy which was performed 1 year and 1 month after the start of symptoms. The favorable development is encouraging in that a new orientation in the management of Perthes’ disease is possible.

Supplementary data

A chronological overview and fi gures covering both hips are available as supplementary data in the online version of the article http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1298020.

No competing interests declared.

ALM wrote the manuscript. FB provided osteological expertise and reviewed the manuscript. KB operated on the patient. GES was the treating physician and kept patient records.

IORT_A_1298020_SUPP.PDF

Download PDF (1.3 MB)- Adami S, Libanati C, Boonen S, Cummings S R, Ho P R, Wang A, Siris E, Lane J; FREEDOM Fracture-Healing Writing Group, Adachi J D, Bhandari M, de Gregorio L, Gilchrist N, Lyritis G, Möller G, Palacios S, Pavelka K, Heinrich R, Roux C, Uebelhart D. Denosumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis does not interfere with fracture healing: results from the FREEDOM trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94 (23): 2113–9.

- Agarwala S, Jain D, Joshi V R, Sule A. Efficacy of alendronate, a bisphosphonate, in the treatment of AVN of the hip. A prospective open-label study. Rheumatol 2005; 44 (3): 352–9.

- Aspenberg P. Denosumab and atypical femoral fractures. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (1): 1–2.

- Camacho N P, Raggio C L, Doty S B, Root L, Zraick V, Ilg W A, Toledano T R, Boskey A L. A controlled study of the effects of alendronate in a growing mouse model of osteogenesis imperfecta. Calcif Tissue Int 2001; 69 (2): 94–101.

- Catterall A. The natural history of Perthes’ disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1971; 53 (1): 37–53.

- Gerstenfeld L C, Sacks D J, Pelis M, Mason Z D, Graves D T, Barrero M, Ominsky M S, Kostenuik P J, Morgan E F, Einhorn T A. Comparison of effects of the bisphosphonate alendronate versus the RANKL inhibitor denosumab on murine fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res 2009; 24 (2): 196–208.

- Grasemann C, Schündeln M M, Hövel M, Schweiger B, Bergmann C, Herrmann R, Wieczorek D, Zabel B, Wieland R, Hauffa B P. Effects of RANK-ligand antibody (denosumab) treatment on bone turnover markers in a girl with juvenile Paget’s disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98 (8): 3121–6.

- Hoyer-Kuhn H, Franklin J, Allo G, Kron M, Netzer C, Eysel P, Hero B, Schoenau E, Semler O. Safety and efficacy of denosumab in children with osteogenesis imperfecta - a first prospective trial. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 2016; 16 (1): 24–32.

- Hyman J E, Trupia E P, Wright M L, Matsumoto H, Jo C H, Mulpuri K, Joseph B, Kim H K and the International Perthes Study Group Members. Interobserver and intraobserver reliability of the modified Waldenström classification system for staging of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015; 97 (8): 643–50.

- Joseph B, Varghese G, Mulpuri K, Narasimha Rao K, Nair NS. Natural evolution of Perthes‘disease: a study of 610 children under 12 years of age at disease onset. J Pediatr Orthop 2003; 23 (5): 590–600.

- Kim H K, Randall T S, Bian H, Jenkins J, Garces A, Bauss F. Ibandronate for prevention of femoral head deformity after ischemic necrosis of the capital femoral epiphysis in immature pigs. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87 (3): 550–7.

- Kim H K, Morgan-Bagley S, Kostenuik P. RANKL inhibition: a novel strategy to decrease femoral head deformity after ischemic osteonecrosis. J Bone Miner Res 2006; 21 (12): 1946–54.

- Kim H K. Pathophysiology and new strategies for the treatment of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94 (7): 659–69.

- Kobayashi E, Setsu N. Osteosclerosis induced by denosumab. Lancet 2015; 385 (9967): 539.

- Lange T, Stehling C, Fröhlich B, Klingenhöfer M, Kunkel P, Schneppenheim R, Escherich G, Gosheger G, Hardes J, Jürgens H, Schulte T L. Denosumab: a potential new and innovative treatment option for aneurysmal bone cysts. Eur Spine J 2013; 22 (6): 1417–22.

- Lee Y K, Ha Y C, Cho Y J, Suh K T, Kim S Y, Won Y Y, Min B W, Yoon T R, Kim H J, Koo K H. Does zoledronate prevent femoral head collapse from osteonecrosis? A prospective, randomized, open-label, multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015; 97 (14): 1142–8.

- Lepola V T, Hannuniemi R, Kippo K, Lauren L, Jalovaara P, Vaananen H K. Long-term effects of clodronate on growing rat bone. Bone 1996; 18 (2): 191–196.

- Meiss A L. MRT zur Diagnostik des Containment-Verlustes beim Morbus Perthes. Medizinisch-Orthopädische Technik 2001; 121 (2): 47–54.

- Ombrédanne L. Précis clinique et opératoire de chirurgie infantile. Masson et Cie, Paris, 1923; II: 855–6.

- Perkins G. Signs by which to diagnose congenital dislocation of the hip. Lancet 1928; 1: 648–50.

- Salter R B, Thompson G H. Legg-Calvé-Perthes‘disease. The prognostic significance of the subchondral fracture and a two-group classification of the femoral head involvement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1984; 66 (4): 479–89.

- Schilcher J, Aspenberg P. Atypical fracture of the femur in a patient using denosumab – a case report. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (1): 6–7.

- Setsu N, Kobayashi E, Asano N, Yasui N, Kawamoto H, Kawai A, Horiuchi K. Severe hypercalcemia following denosumab treatment in a juvenile patient. J Bone Miner Metab 2016; 34 (1): 118–22.

- Stulberg S D, Cooperman D R, Wallensten R. The natural history of Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981; 63 (7): 1095–108.

- Wang H D, Boyce A M, Tsai J Y, Gafni R I, Farley F A, KasaVubu J Z, Molinolo A A, Collins M T. Effects of denosumab treatment and discontinuation on human growth plates. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014; 99 (3): 891–897.

- Young M L, Little D G, Kim H K. Evidence for using bisphosphonate to treat Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012; 470 (9): 2462–75.