Abstract

Background and purpose — Most registry studies regarding highly crosslinked polyethylene (XLPE) have focused on the overall revision risk. We compared the risk of cup and/or liner revision for specific cup and liner designs made of either XLPE or conventional polyethylene (CPE), regarding revision for any reason and revision due to aseptic loosening and/or osteolysis.

Patients and methods — Using the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association (NARA) database, we identified cup and liner designs where either XLPE or CPE had been used in more than 500 THAs performed for primary hip osteoarthritis. We assessed risk of revision for any reason and for aseptic loosening using Cox regression adjusted for age, sex, femoral head material and size, surgical approach, stem fixation, and presence of hydroxyapatite coating (uncemented cups).

Results — The CPE version of the ZCA cup had a risk of revision for any reason similar to that of the XLPE version (p = 0.09), but showed a 6-fold higher risk of revision for aseptic loosening (p < 0.001). The CPE version of the Reflection All Poly cup had an 8-fold elevated risk of revision for any reason (p < 0.001) and a 5-fold increased risk of revision for aseptic loosening (p < 0.001). The Charnley Elite Ogee/Marathon cup and the Trilogy cup did not show such differences.

Interpretation — Whether XLPE has any advantage over CPE regarding revision risk may depend on the properties of the polyethylene materials being compared, as well as the respective cup designs, fixation type, and follow-up times. Further research is needed to elucidate how cup design factors interact with polyethylene type to affect the risk of revision.

Highly crosslinked polyethylene (XLPE) was introduced during the late 1990s to address the problem of wear-induced periprosthetic osteolysis and loosening of THAs. Laboratory studies showed favorable wear characteristics of XLPE of different brands, and with differing manufacturing methods (McKellop et al. Citation1999, Muratoglu et al. Citation2001, Oral et al. Citation2004, Dumbleton et al. Citation2006). 1 meta-analysis (Kurtz et al. Citation2011) and 1 review article (Callary et al. Citation2015) covering different methods for in vivo wear measurement have reported markedly less wear in cemented and uncemented cups with XLPE than in those with CPE, after up to 10 years of follow-up. Meta-analyses on clinical studies have found a reduced incidence of acetabular osteolysis around uncemented implants with XLPE (Kurtz et al. Citation2011, Kuzyk et al. Citation2011). On the other hand, our group failed to show any improvement in long-term implant fixation or occurrence of osteolysis at 10 years for a cemented cup consisting of either CPE or XLPE (Johanson et al. Citation2012). 2 recent meta-analyses (Shen et al. Citation2014, Wyles et al. Citation2015) reported that there was no reduced revision risk with XLPE implants. 1 prospective randomized study found a lower revision risk with XLPE than with CPE (Engh et al. Citation2012). As for observational studies, some registries have reported lower revision rates for XLPE hip implants (AOANJRR 2015, Paxton et al. Citation2015), but a combined analysis failed to demonstrate such an effect (Paxton et al. Citation2014).

It is therefore still unclear whether XLPE offers any advantage over CPE regarding the overall risk of revision, and specifically the incidence of revision for osteolysis and aseptic loosening.

We analyzed the Nordic Arthroplasty Registry Association (NARA) database to determine whether the use of XLPE would mean a reduced risk of revision for any reason and also for aseptic loosening. In order to investigate the impact of design-specific analysis, we performed an overall comparison between XLPE and PE based on the fixation principle, including all available cups (all designs), and compared it to an analysis of specific cup and liner designs for the corresponding time period.

Patients and methods

The Nordic Arthroplasty Registry Association (NARA)

The NARA was founded in 2007, engaging the hip and knee arthroplasty registries in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden (Havelin et al. Citation2009). Finland joined the NARA in 2010 (Makela et al. Citation2014). The database from 2013 contains data on 620,261 THAs performed since 1995, with the following information: anonymous patient code, age at surgery, sex, date of primary surgery, hospital, diagnosis, laterality, surgical incision, femoral and acetabular implant type, femoral head size, and material. Furthermore, the date, type, and cause of revision are recorded for revised patients and the date of death or emigration is registered where applicable.

Data are completed, extracted, and de-identified within each participating registry before being merged into a common database.

We used data from the registries of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden—but not Finland, since the Finnish Registry data do not contain specific information for identification of cup revisions.

Inclusion criteria—all cup designs

For the analysis of all cup designs, we identified THAs performed because of primary hip osteoarthritis and assigned them to either of 2 analysis groups, based on cup fixation.

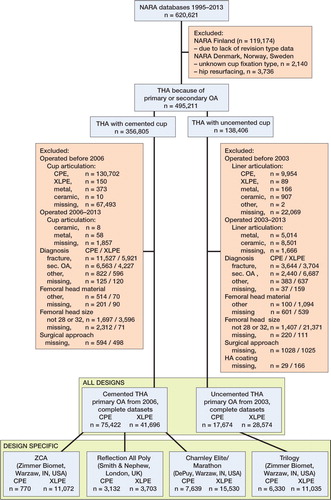

There were few CPE cups with large (> 32-mm) femoral heads, and for that reason we included only cups with femoral head sizes of 28 or 32 mm, both metal and ceramic. We chose to start the analysis at the year when the total number of recorded THAs with XLPE exceeded 100—for cemented cups, 2006, and for uncemented cups, 2003. This time point corresponded well to the main increase in XLPE usage in the NARA database, and also to a distinct decrease in missing data on cup/liner material. Since revision rates may vary with time, we also chose to include CPE cases starting from the same year, which made the mean follow-up times between groups more equal. Cases with unknown cup material or missing values for any of the adjustment variables were discarded. The study group selection sequence is given in .

Inclusion criteria—specific cup designs

From the 2 all-design groups, we identified cup designs where more than 500 operations had been performed using both conventional (CPE) and highly crosslinked polyethylene (XLPE) versions, with a mean and maximum follow-up of at least 2 years and 5 years, respectively. Cup geometries should be equal or close to equal for CPE and XLPE versions of each design; only minor variations in shape of peripheral flanges were accepted (Table 1, see Supplementary data).

Follow-up limit

The follow-up limit for each design in the design-specific analysis and for each fixation type in the all-design analysis was the time point at which there were still 100 operations at risk in the smallest group. Remaining non-revised hips were censored at the follow-up limit.

Definition of revision

We defined revision as exchange or extraction of an acetabular component including liner exchange, with or without concomitant stem exchange/extraction.

Statistics

For each cup group analyzed we prepared a Kaplan-Meier graph on cumulative survival.

We also used adjusted Cox regression analysis with type of polyethylene as the risk factor of interest. The full set of adjusting variables consisted of age at surgery (Santaguida et al. Citation2008, Prokopetz et al. Citation2012), sex (Santaguida et al. Citation2008, Prokopetz et al. Citation2012), femoral head size (28 or 32 mm) (Jameson et al. Citation2012, Prokopetz et al. Citation2012), femoral head material (metal/ceramic) (Thien and Karrholm Citation2010), stem fixation (cemented/uncemented) (Hailer et al. Citation2010), surgical approach (posterolateral approach/other) (Lindgren et al. Citation2012), and—for uncemented cups—the presence or absence of hydroxyapatite coating of the cup shell (Lazarinis et al. Citation2010).

The proportional hazards (PH) assumption was evaluated using a combination of log-minus-log plots, plots of scaled Schoenfeld residuals, and Schoenfeld tests. If the risk factor of interest violated the PH assumption, we split the dataset at a breakpoint chosen by the log-minus-log plot. When adjusting variables violated the PH assumption, we used stratified Cox models. In such cases, continuous variables were categorized into quartiles. 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported for hazard ratios.

Missing cases and collinearity

Of all cases with non-missing polyethylene type, the total percentage of cases that were discarded because of missing data on any adjusting variable was 2.9% in the cemented group and 4.8% in the uncemented group.

In a Spearman correlation test, the risk factors femoral head material and stem fixation in the Reflection All Poly group had the highest correlation (Spearman ρ = 0.63). All other risk factor combinations in all analysis groups had lower correlations (83% had Spearman ρ < 0.3). The variance inflation factor of all variables in all subgroups was never higher than 2.01, corresponding to an acceptable level of multicollinearity (Menard Citation2002)

Sensitivity analysis

For designs where the number of events per variable (EPV) was ≤10, we checked the Cox models by calculating bias-corrected estimates and confidence intervals based on 1,000 bootstrap resamplings, and also compared Wald- and likelihood ratio-based p-values (Peduzzi et al. Citation1995, Vittinghoff and McCulloch Citation2007, Vittinghoff et al. Citation2012).

We defined the percentage of bilateral cases for each analysis category and performed a sensitivity analysis with only the first-operated hip included (Ranstam et al. Citation2011). Bilaterally operated patients with differing cup fixation (all-design analysis) or differing cup design (design-specific analysis) were counted as being unilaterally operated within each analysis group.

We also compared Cox regression models with the corresponding competing-risk model, using death as competing risk (Ranstam et al. Citation2011). Since competing-risks estimation in our software does not allow for stratified analyses, we compared regular Cox regression and competing-risks regression with all risk factors entered as main effects.

Influence of missing data regarding cup or liner material for each analysis category was assessed by assigning all cases with missing data to either all-CPE or all-XLPE and examining the influence on the main results.

In cup groups with a sufficient number of cases with 36-mm femoral heads, we performed a sensitivity analysis for all-cause revision risk.

Reporting and significance level

Results are reported as hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values. We used a 5% significance level. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 and Stata IC 13.1.

Ethics

The dataset was processed in compliance with the national regulations governing research on registry data in each participating country. Extraction and evaluation of the Swedish dataset was approved by the local ethics committee in Gothenburg (348-13/T144-14). No competing interests declared.

Results

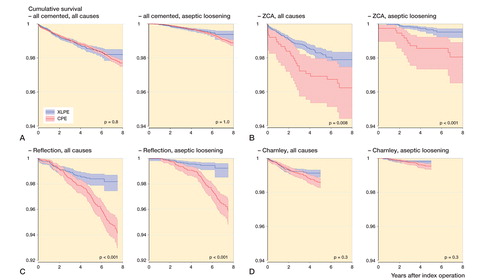

Cemented cups―all designs

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis regarding revision for any reason and revision for aseptic loosening did not reveal any statistically significant differences between XLPE and CPE ().

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier cumulative survival curves with 95% confidence intervals for all cemented designs (panel A), ZCA (B), Reflection All Poly (C), and Charnley Elite Ogee/Marathon (D) cups. The follow-up time ended when there were 100 cases at risk in the smallest group (always XLPE). P-values from log-rank test.

Also, the corresponding adjusted Cox regressions did not detect any significant differences in risk of revision for any reason (HRCPE/XLPE = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.81–1.1; p = 0.4) or aseptic loosening (HRCPE/XLPE = 1.2, 95% CI: 0.89–1.6; p = 0.2) (see Supplementary data).

Cemented cups―specific designs

3 cemented cup designs, ZCA (Zimmer, Warzaw, IN), Reflection Cemented (Smith and Nephew, London, UK), and Charnley Elite Ogee (CPE)/Marathon(XLPE) (DePuy Synthes, Warzaw, IN) fulfilled the inclusion criteria for design-specific analysis (see Supplementary data).

The XLPE versions of ZCA and Reflection All Poly cups showed a higher unadjusted survival than their CPE versions, but no statistically significant difference in survival was detected for the Charnley/Marathon cups ().

Results for the corresponding adjusted Cox regressions are listed in Table 2a and b (Supplementary data). The ZCA cup had a non-significantly elevated revision risk of revision for any reason (HRCPE/XLPE = 1.6, 95% CI: 0.94–2.6; p = 0.09) and a higher risk of revision for aseptic loosening in the CPE group (HRCPE/XLPE = 6.1, 95% CI: 2.3–16); p < 0.001). The XLPE version of the Reflection All Poly cup showed a lower risk of revision for any reason (HRCPE/XLPE = 1.8, 95% CI: 1.1–3.0; p = 0.03 (0–4 years); HRCPE/XLPE = 7.8, 95% CI: 3.0–20; p < 0.001 (4–7.5 years)) and also for aseptic loosening (HRCPE/XLPE = 5.3, 95% CI: 2.8–10; p < 0.001) compared to the CPE version. No such difference could be detected for Charnley Elite Ogee/Marathon cups (all reasons: HRCPE/XLPE = 1.1, 95% CI: 0.74–1.5; p = 0.8; aseptic loosening: HRCPE/XLPE = 1.4, 95% CI: 0.67–2.8; p = 0.4). However, in this last group, there were only 7 revisions for any reason past 2 years of follow-up in 6,971 remaining XLPE hips, as compared to 47 in the remaining 6,938 CPE hips. The corresponding figures for aseptic loosening were 3 and 22.

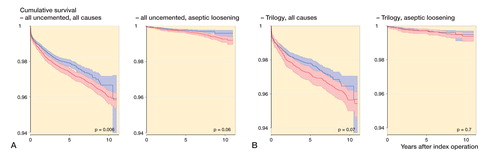

Uncemented cups―all designs

The Kaplan-Meier analysis showed significantly lower survival in the CPE group for all-reason revision but not for aseptic loosening (). In the adjusted Cox regression, the revision risk ratio appeared similar for revision for any reason (HRCPE/XLPE = 1.0, 95% CI: 0.86–1.2; p = 0.9), but with a statistically non-significantly increased risk of revision for aseptic loosening in the CPE group (HRCPE/XLPE = 1.5, 95% CI: 0.93–2.3; p = 0.1) (see Supplementary data).

Uncemented cups―specific designs

1 uncemented cup design, Trilogy (Zimmer, Warzaw, IN) fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The Kaplan-Meier analysis detected similar revision rates with CPE and XLPE liners (). The adjusted risk of revision for any reason or for aseptic loosening did not differ significantly up to 11 years (HRCPE/XLPE = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.73–1.2; p = 0.5; and HRCPE/XLPE = 0.89, 95% CI: 0.45–1.7; p = 0.7, respectively) (see Supplementary data).

Sensitivity analyses

All Wald- and likelihood ratio-based p-values and also bootstrap-estimated bias-corrected estimates and confidence intervals were consistent for the risk factor polyethylene type.

Exclusion of the second operation in bilateral cases in each group did not influence the results.

Competing-risk analysis gave similar results to conventional Cox regression. Inclusion of cases with missing information on cup material in the analysis as either XLPE or CPE did not change the results.

We found 1,011 CPE cups with 36-mm femoral heads. 23 cups were revised for any reason and 2 were revised for aseptic loosening. The corresponding figures for XLPE cups were 21,975, 327, and 63, respectively. Sensitivity analyses including the cemented and uncemented all-design groups did not affect the adjusted all-cause revision risks (data not shown). There were no statistically significant differences in adjusted all-cause revision risks between 28-, 32-, and 36-mm femoral heads in the all-design XLPE cup groups (data not shown).

Discussion

We analysed cemented and uncemented cups separately and also 4 specific cup designs, 3 cemented and 1 uncemented, where both conventional and highly crosslinked polyethylene had been used in more than 500 hips. We did not detect any statistically significantly reduced revision risk for XLPE cups or liners compared to CPE in the 2 all-design groups, but there was a reduced risk of revision for some of the designs analyzed.

Cemented cups

2 specific designs with the same follow-up time, ZCA and Reflection All Poly, showed a reduced risk of revision due to cup loosening/osteolysis when used with XLPE. The XLPE version of the Reflection All Poly cup also showed a reduced overall revision risk. The Australian registry has reported a significantly higher risk of revision for all reasons when comparing non-crosslinked PE with highly crosslinked PE in the Reflection All Poly cup (AOANJRR 2015), which is consistent with our findings. The Reflection All Poly CPE cup was sterilized with ethylene oxide, which could at least partly explain this difference. We have not found any comparisons regarding the other 2 designs analyzed, and also no comparisons for cemented cups in general or comparisons for aseptic loosening and osteolysis.

The analysis of Charnley Elite Ogee/Marathon cups showed no difference in revision risk between PE types. Marathon XLPE is γ-irradiated with 50 kGy, a dose that is 45% and 50% lower than with the other 2 XLPE cups that were included. In addition, this design has a shorter follow-up than the other cemented designs, and according to the Kaplan-Meyer diagram a difference in risk may be discovered with longer follow-up and more cases.

Uncemented cups

When we analyzed all-design uncemented cups with adjustment for confounders, XLPE showed no reduced risk of revision for aseptic loosening. This finding corresponds to an earlier registry study (Paxton et al. Citation2014). A smaller registry study by the same author (Paxton et al. Citation2015) showed an advantage of XLPE over CPE regarding both total revision risk and the risk of aseptic revision. This study also reported 2 design-specific comparisons, with the same results for the 2 types of revision. The Australian registry reported a decreased total revision risk for XLPE from 3 months (AOANJRR 2012) and also a decreased risk of revision for aseptic loosening from 3–4 years of follow-up (AOANJRR 2013) for the group containing all cup designs. The only specific design studied by us, Trilogy, did not show any difference in terms of cup revision related to choice of liner material after 11 years of follow-up. The Australian registry reported design-specific comparisons with a comparable follow-up time, analyzed with regard to revision for any reason and adjusted for age and sex, and had varying results. 4 out of 5 designs analyzed showed a lower revision risk with XLPE (AOANJRR 2015).

General remarks

Design-specific approaches from our group and others have shown varying outcomes regarding risk of revision. These findings could have several possible explanations. XLPE is a heterogenous group representing different manufacturing processes, the impact of which on clinical performance is largely unknown. Also, CPE is a heterogenous group with some types notably more prone to wear than others (Digas et al. Citation2003, Kadar et al. Citation2011). In addition, interacting mechanisms between polyethylene and implant design (e.g. stem and cup designs, couplings, and non-polyethylene materials) may improve or deteriorate performance in unpredictable ways. One such example observed in both laboratory (Atwood et al. Citation2011) and in case studies (Waewsawangwong and Goodman Citation2012, Ast et al. Citation2014) is the use of elevated rims or thin polyethylene sections that may fracture, due to inferior mechanical properties of certain XLPE types.

The reduced wear in XLPE could be expected to result in a reduced revision rate due to aseptic loosening no sooner than 5 years (Harris Citation1995), and perhaps more likely beyond 7 years (Hallan et al. Citation2010). Conversely, oxidative degradation of XLPE could increase failure rates with longer follow-up (Currier et al. Citation2010, Atwood et al. Citation2011), but to date this has not been observed.

Limitations

We adjusted for known or proposed risk factors that are likely to influence the risk of revision. However, residual confounding as well as surgeon performance and patient selection bias cannot be ruled out. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or even meta-analyses of RCTs run the risk of failing to detect clinically relevant correlations due to insufficient power. However, observational registry studies are as yet the only practical means of analyzing revision risks within reasonable time spans.

We excluded THA with a femoral head diameter of >32 mm, since these sizes occurred almost exclusively in XLPE hips. Others have reported more use of heads with diameters larger than 32 mm in XLPE hips (AOANJRR 2013), due to lower dislocation risk (Howie et al. Citation2012) and favorable wear results (Bragdon et al. Citation2007). However, large metal heads may be associated with trunnion corrosion (Esposito et al. Citation2014), which could counteract the benefits of lower dislocation rates with larger heads. A sensitivity analysis showed no influence on the overall difference in revision risk between XLPE and CPE, but this relationship may still have been over- or underestimated in our study. Further studies with longer follow-up are needed to address this issue.

For some designs, the number of events was low and sometimes close to the events-per-predictor limit. Few events per risk factor analyzed can produce biased estimates and confidence intervals (Vittinghoff and McCulloch Citation2007). Our model evaluations, on the other hand, indicate that the models reported are reasonable. Even so, our results should be confirmed in larger studies with longer follow-up.

Conclusion

XLPE had a lower risk of revision than PE in some cemented cups with at least 7.5 years of follow-up, as shown in our design-specific analysis. The difference was more pronounced with revision for aseptic loosening. Such a difference was not detectable for a cup design with shorter follow-up or when we analyzed an all-design cup population with the same length of follow-up. For uncemented cups, we found similar revision risk for XLPE and CPE, even with 11-year follow-up. Based on our findings of different results from our multi-design and design-specific analyses and on findings by others (AOANJRR 2015), we believe that design-specific analysis is the most accurate way of comparing the performance of biomaterials in vivo. Design factors may affect the expected benefit of XLPE, and should be studied further.

Supplementary data

Tables 1–3 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1307676.

PJ and JK wrote the manuscript. PJ performed the statistical analyses. OF, LH, AF, AP, GG, KM, and JK participated in the study design, data collection, and revision of the manuscript.

We thank NordForsk, the Felix Neubergh Research Foundation, Gothenburg Medical Society, and the Swedish Government (ALF) for financial support.

AOANJRR. Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Annual report. 2012.

AOANJRR. Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Annual report. 2013.

AOANJRR. Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Annual report. 2015.

IORT_A_1307676_SUPP.PDF

Download PDF (40.2 KB)- Ast M P, John T K, Labbisiere A, Robador N, Valle A G. Fractures of a single design of highly cross-linked polyethylene acetabular liners: an analysis of voluntary reports to the United States Food and Drug Administration. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29 (6): 1231–5.

- Atwood S A, Van Citters D W, Patten E W, Furmanski J, Ries M D, Pruitt L A. Tradeoffs amongst fatigue, wear, and oxidation resistance of cross-linked ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2011; 4 (7): 1033–45.

- Bragdon C R, Greene M E, Freiberg A A, Harris W H, Malchau H. Radiostereometric analysis comparison of wear of highly cross-linked polyethylene against 36- vs 28-mm femoral heads. J Arthroplasty 2007; 22 (6 Suppl 2): 125–9.

- Callary S A, Solomon L B, Holubowycz O T, Campbell D G, Munn Z, Howie D W. Wear of highly crosslinked polyethylene acetabular components. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (2): 159–68.

- Currier B H, Van Citters D W, Currier J H, Collier J P. In vivo oxidation in remelted highly cross-linked retrievals. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92 (14): 2409–18.

- Digas G, Thanner J, Nivbrant B, Rohrl S, Strom H, Karrholm J. Increase in early polyethylene wear after sterilization with ethylene oxide: radiostereometric analyses of 201 total hips. Acta Orthop Scand 2003; 74 (5): 531–41.

- Dumbleton J H, D’Antonio J A, Manley M T, Capello W N, Wang A. The basis for a second-generation highly cross-linked UHMWPE. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 453: 265–71.

- Engh C A, Jr., Hopper R H, Jr., Huynh C, Ho H, Sritulanondha S, Engh C A, Sr. A prospective, randomized study of cross-linked and non-cross-linked polyethylene for total hip arthroplasty at 10-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27 (8 Suppl): 2–7 e1.

- Esposito C I, Wright T M, Goodman S B, Berry D J, Clinical Biological Bioengineering Study Groups from Carl T Brighton Workshop. What is the trouble with trunnions? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472 (12): 3652–8.

- Hailer N P, Garellick G, Karrholm J. Uncemented and cemented primary total hip arthroplasty in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (1): 34–41.

- Hallan G, Dybvik E, Furnes O, Havelin L I. Metal-backed acetabular components with conventional polyethylene: a review of 9113 primary components with a follow-up of 20 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92 (2): 196–201.

- Harris W H. The problem is osteolysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1995; (311): 46–53.

- Havelin L I, Fenstad A M, Salomonsson R, Mehnert F, Furnes O, Overgaard S, Pedersen A B, Herberts P, Karrholm J, Garellick G. The Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association: a unique collaboration between 3 national hip arthroplasty registries with 280,201 THRs. Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (4): 393–401.

- Howie D W, Holubowycz O T, Middleton R. Large femoral heads decrease the incidence of dislocation after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94 (12): 1095–102.

- Jameson S S, Baker P N, Mason J, Gregg P J, Brewster N, Deehan D J, Reed M R. The design of the acetabular component and size of the femoral head influence the risk of revision following 34 721 single-brand cemented hip replacements: A retrospective cohort study of medium-term data from a National Joint Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012; 94-B (12): 1611–7.

- Johanson P E, Digas G, Herberts P, Thanner J, Karrholm J. Highly crosslinked polyethylene does not reduce aseptic loosening in cemented THA 10-year findings of a randomized study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012; 470 (11): 3083–93.

- Kadar T, Hallan G, Aamodt A, Indrekvam K, Badawy M, Skredderstuen A, Havelin L I, Stokke T, Haugan K, Espehaug B, Furnes O. Wear and migration of highly cross-linked and conventional cemented polyethylene cups with cobalt chrome or Oxinium femoral heads: a randomized radiostereometric study of 150 patients. J Orthop Res 2011; 29 (8): 1222–9.

- Kurtz S M, Gawel H A, Patel J D. History and systematic review of wear and osteolysis outcomes for first-generation highly crosslinked polyethylene. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011; 469 (8): 2262–77.

- Kuzyk P R T, Saccone M, Sprague S, Simunovic N, Bhandari M, Schemitsch E H. Cross-linked versus conventional polyethylene for total hip replacement: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93B (5): 593–600.

- Lazarinis S, Karrholm J, Hailer N P. Increased risk of revision of acetabular cups coated with hydroxyapatite. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (1): 53–9.

- Lindgren V, Garellick G, Karrholm J, Wretenberg P. The type of surgical approach influences the risk of revision in total hip arthroplasty: a study from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register of 90,662 total hipreplacements with 3 different cemented prostheses. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (6): 559–65.

- Makela K T, Matilainen M, Pulkkinen P, Fenstad A M, Havelin L I, Engesaeter L, Furnes O, Overgaard S, Pedersen A B, Karrholm J, Malchau H, Garellick G, Ranstam J, Eskelinen A. Countrywise results of total hip replacement. An analysis of 438,733 hips based on the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association database. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (2): 107–16.

- McKellop H, Shen F W, Lu B, Campbell P, Salovey R. Development of an extremely wear-resistant ultra high molecular weight polyethylene for total hip replacements. J Orthop Res 1999; 17 (2): 157–67.

- Menard S. Applied logistic regression snalysis. SAGE Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA 2002.

- Muratoglu O K, Bragdon C R, O’Connor D O, Jasty M, Harris W H. A novel method of cross-linking ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene to improve wear, reduce oxidation, and retain mechanical properties: Recipient of the 1999 HAP Paul award. J Arthroplasty 2001; 16 (2): 149–60.

- Oral E, Wannomae K K, Hawkins N, Harris W H, Muratoglu O K. Alpha-tocopherol-doped irradiated UHMWPE for high fatigue resistance and low wear. Biomaterials 2004; 25 (24): 5515–22.

- Paxton E, Cafri G, Havelin L, Stea S, Palliso F, Graves S, Hoeffel D, Sedrakyan A. Risk of revision following total hip arthroplasty: metal-on-conventional polyethylene compared with metal-on-highly cross-linked polyethylene bearing surfaces: international results from six registries. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96 Suppl 1: 19–24.

- Paxton E W, Inacio M C, Namba R S, Love R, Kurtz S M. Metal-on-conventional polyethylene total hip arthroplasty bearing surfaces have a higher risk of revision than metal-on-highly crosslinked polyethylene: results from a US registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015; 473 (3): 1011–21.

- Peduzzi P, Concato J, Feinstein A R, Holford T R. Importance of events per independent variable in proportional hazards regression analysis II. Accuracy and precision of regression estimates. J Clin Epidemiol 1995; 48 (12): 1503–10.

- Prokopetz J, Losina E, Bliss R, Wright J, Baron J, Katz J. Risk factors for revision of primary total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2012; 13: 251.

- Ranstam J, Karrholm J, Pulkkinen P, Makela K, Espehaug B, Pedersen A B, Mehnert F, Furnes O. NARA study group. Statistical analysis of arthroplasty data. II. Guidelines. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (3): 258–67.

- Santaguida P L, Hawker G A, Hudak P L, Glazier R, Mahomed N N, Kreder H J, Coyte P C, Wright J G. Patient characteristics affecting the prognosis of total hip and knee joint arthroplasty: a systematic review. Can J Surg 2008; 51 (6): 428–36.

- Shen C, Tang Z H, Hu J Z, Zou G Y, Xiao R C, Yan D X. Does cross-linked polyethylene decrease the revision rate of total hip arthroplasty compared with conventional polyethylene? A meta-analysis. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2014; 100 (7): 745–50.

- Thien T M, Karrholm J. Design-related risk factors for revision of primary cemented stems. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (4): 407–12.

- Vittinghoff E, McCulloch C E. Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and Cox regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2007; 165 (6): 710–8.

- Vittinghoff E, Glidden D V, Shiboski S C, McCulloch, C E. Regression methods in biostatistics, 2nd Ed. Springer 2012.

- Waewsawangwong W, Goodman S B. Unexpected failure of highly cross-linked polyethylene acetabular liner. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27 (2): 323 e1–4.

- Wyles C C, Jimenez-Almonte J H, Murad M H, Norambuena-Morales G A, Cabanela M E, Sierra R J, Trousdale R T. There Are No Differences in Short- to Mid-term Survivorship Among Total Hip-bearing Surface Options: A Network Meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015; 473 (6): 2031–41.