Abstract

Background and purpose — Displaced femoral neck fractures (FNFs) are associated with high rates of mortality during the first postoperative year. The Sernbo score (based on age, habitat, mobility, and mental state) can be used to stratify patients into groups with different 1-year mortality. We assessed this predictive ability in patients with a displaced FNF treated with a hemiarthroplasty or a total hip arthroplasty.

Patients and methods — 292 patients (median age 83 (65–99) years, 68% female) with a displaced FNF were included in this prospective cohort study. To predict 1-year mortality, we used a multivariate logistic regression analysis including comorbidities and perioperative management. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to evaluate the predictive ability of the Sernbo score, which was subsequently divided in a new manner into a low, intermediate, or high risk of death during the first year.

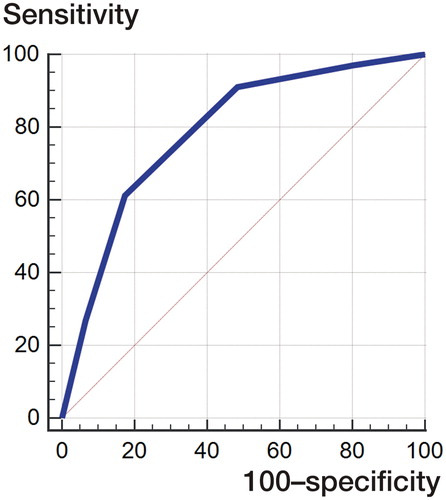

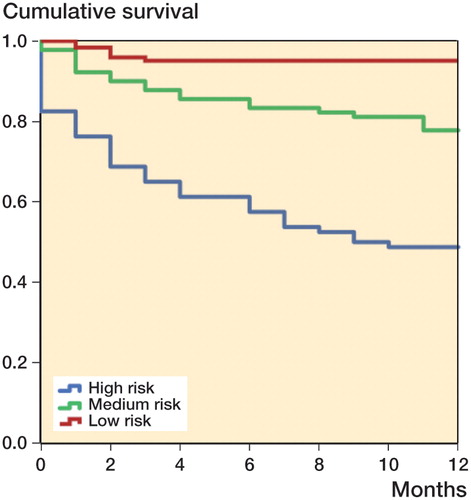

Results — At 1-year follow-up, the overall mortality rate was 24%, and in Sernbo’s low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups it was 5%, 22%, and 51%, respectively. The Sernbo score was the only statistically significant predictor of 1-year mortality: odds ratio for the intermediate-risk group was 4.2 (95% Cl: 1.5–12) and for the high-risk group it was 15 (95% CI: 5–40). The ROC analysis showed a fair predictive ability of the Sernbo score, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.73–0.83). Using a cutoff of less than 11 points on the score gave a sensitivity of 61% and a specificity of 83%.

Interpretation — The Sernbo score identifies patients who are at high risk of dying in the first postoperative year. This scoring system could be used to better tailor perioperative care and treatment in patients with displaced FNF.

Hip fracture patients are plagued with a high 1-year mortality rate ranging between 8% and 36% (Abrahamsen et al. Citation2009). Perioperative care of elderly and frail patients with displaced femoral neck fractures (FNFs) might be improved by an accurate estimation of postoperative morbidity and mortality, since such data could call for a more detailed preoperative optimization of comorbidities, perhaps serve as a guide to the most optimal choice of surgical method, and aid in timing of surgery. A number of scoring systems have been used to predict mortality after hip fractures. The most commonly used ones are the physiological and operative severity score for the enumeration of mortality and morbidity (POSSUM) (Mohamed et al. Citation2002, van Zeeland et al. Citation2011), the Charlson comorbidity index score (Kirkland et al. Citation2011), and the Nottingham hip fracture score (Wiles et al. Citation2011). These scoring systems are, however, based on detailed information on comorbidities, which can be difficult to obtain in elderly patients during the initial acute setting. The Sernbo score is a 4-component score (including age, social situation, mobility, and mental state) that was initially developed as a tool for decision making regarding treatment with either a total hip arthroplasty (THA) or a hemiarthroplasty (HA) (Leonardsson et al. Citation2010). This simple score can be calculated using information obtained during routine orthopedic patient assessment.

We assessed the Sernbo score in predicting 1-year mortality after hip replacement for a displaced FNF in elderly patients.

Patients and methods

Study setting

This observational, prospective cohort study was performed between 2012 and 2015 at the Orthopedics Department of Sundsvall Hospital, Sweden. Sundsvall Hospital is an emergency hospital with a catchment area of approximately 160,000 inhabitants.

Patients

We included all patients aged over 65 years with an acute displaced FNF treated with either HA or THA between February 2012 and February 2015. All non-displaced FNFs and pathological fractures were excluded. The routine at our department is to perform hip arthroplasty for displaced FNF in patients over 65 years of age. THA is used in the relatively younger patients (65–79 years), in more active patients, and in those with rheumatoid or osteoarthritic changes in the affected hip. HA is used in older patients (> 79 years) who are less active and have lower demands, in those with a short life expectancy, and in those with cognitive dysfunction.

Data collection

Data were collected prospectively throughout the study period from a combination of in-hospital surgical and medical records, at admission and during the follow-up period of at least 1 year (or until death). Patient data included age, sex, preoperative comorbidities, ASA score, preoperative hemoglobin and serum creatinine, type of arthroplasty (THA/HA), and surgical approach (). The Sernbo score includes age, habitat, walking aids, and mental status—giving from 8 up to a maximum of 20 points in 5 increments (). 3 empirical mortality-risk subgroups were subsequently formed: low risk (20 or 17 points), intermediate risk (14 points), and high risk (11 or 8 points), based on potential subgroups that would have clinically useful differences in mortality.

Table 1. Details of the Sernbo score

Table 2. Patient demographics based on the patients’ preoperative medical recordsTable Footnotea. Values are number of cases (percent) unless otherwise specified

Implant and surgery

A cemented total hip arthroplasty (THA) or hemiarthroplasty (HA) was used in all patients (Lubinus SP2; Waldemar Link, Hamburg, Germany) with either a modular 32-mm cobalt-chrome femoral head or a uni/bipolar head. Patients were operated either using a direct lateral approach (Hardinge Citation1982) or a posterolateral approach (Moore Citation1957) according to the surgeon’s preference. Prophylactic antibiotics (cloxacillin, 2 g; Meda, Solna, Sweden) were administered 30 min preoperatively and 2 more doses were given within 24 h after surgery. Low-molecular-weight heparin was administered postoperatively. The patients were encouraged to do full weight bearing as soon as possible, under the supervision of a physiotherapist. No restrictions were applied to patients who were operated with the lateral approach, while those operated with a posterolateral approach were instructed to avoid flexion beyond 90 degrees, adduction, and internal rotation of the operated hip. Primary surgeries were performed either by a consultant orthopedic surgeon or a registrar.

Preoperative and postoperative care

The hip fracture patients in the study were included in a fast-track system, which is routine in our hospital. The ambulance personnel transported the patient on the ambulance trolley directly to the Radiology Department. After radiographs were taken, the patient was transferred to the emergency department for primary assessment. The orthopedic surgeon on call conducted the physical examination, evaluation of radiographs, pain management with fascia iliaca block, scheduling for surgery, and admission to the ward. The preoperative optimization included cardiovascular optimization by the anesthetist on call.

The postoperative care at the orthopedic department included a team with an orthopedic surgeon and a specialist in geriatric medicine.

Statistics

Categorical variables associated with mortality were evaluated using the chi-squared test. Significant variables were then included in a multivariate logistic regression analysis to predict mortality, and the results are presented as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). The Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used to assess goodness of fit. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to calculate the predictive ability of the Sernbo score and to determine its sensitivity and specificity. The significance level was set at 0.05. To validate the mortality subgroups, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used with log-rank test. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics software version 22.0 and using the MedCalc program for the ROC analysis.

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interests

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the regional ethics committee of Umeå University (entry nos. 2011/428-31, 2016/534-32).

Financial support was received from the Visare Norr Fund, Northern County Councils. No competing interests declared.

Results

Patients and descriptive data 297 patients with a displaced FNF were treated with either HA (82%) or THA (18%). Their median age was 82 (65–99) years, and 203 (68%) of them were women. During the study period, 7 patients had had bilateral surgery for a displaced FNF. 5 of these sustained their contralateral fracture during the first postoperative year, and were therefore excluded (n = 292). None of the patients were lost to follow-up. Further baseline data are presented in . The distribution of patients in each increment of the Sernbo score are shown in Figure 1 (see Supplementary data).

Mortality

The 1-year mortality was 24% in the whole study group. The mortality according to Sernbo score is presented in , with the distribution of patients in each increment. According to the previous subclassification of the Sernbo score, 41% of patients had a low mortality risk, 31% had an intermediate risk, and the remaining 28% formed the high-risk group. The mortality in each group was 5%, 22%, and 51%, respectively. According to the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, these differences were statistically significant (). The mortality subgroups intermediate risk and high risk, increasing age, and surgery using hemiarthroplasty were predictive of 1-year mortality in the univariate statistical analyses (Table 4, see Supplementary data). The multivariate analysis generated a final model () including the Sernbo intermediate mortality risk group (OR =4.2, 95% CI: 1.5–12) and the Sernbo high mortality risk group (OR =15, 95% CI: 5–40). The Hosmer-Lemeshow test for goodness of fit was not significant (chi-square =4.8; p = 0.8, p = 8) and the Nagelkerke R2 was 0.3. Table 6 is a classification table for multivariate logistic regression, showing observed and predicted mortality.

Figure 2. 1-year mortality Kaplan-Meier survivorship curves for the different mortality risk subgroups according to Sernbo score. Log-rank test p < 0.001.

Table 3. The number of patients in each increment of Sernbo score who died

Table 5. Multivariate logistic regression model predicting 1-year mortality. Based on statistically significant variables from the univariate analyses (Table 4).

Receiver operating characteristic (RoC) curve analysis

The ROC curve analyses showed that the Sernbo score predicted mortality with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.79 (95% CI: 0.73–0.83), which is normally classified as a fair degree of accuracy (). Using the Youden index J of 0.44 and the associated cutoff of less than 11 points on the score yielded a sensitivity of 61% and a specificity of 83%. Using each of the Sernbo components alone (i.e. age, habitat, walking ability, and mental status) to predict 1-year mortality generated an AUC of 0.65, 0.68, 0.67, and 0.60, respectively.

Discussion

The expected increase in numbers of patients suffering from a displaced FNF (Rosengren et al. Citation2017) will adversely affect the economics of future healthcare systems. A comparison between the risk and benefits of different treatments and care will therefore be important. In this prospective cohort study, the Sernbo score predicted 1-year mortality with a relatively high degree of accuracy, and patients in the high-risk group were almost 15 times more likely to die than those in the low-risk group after a displaced FNF treated with either HA or THA.

The typical FNF patient is often elderly and frail, with significant comorbidity and a medical history disguised by cognitive impairment and complicated by anticoagulation treatment. The timing of surgery in this population has recently been reviewed (Lewis and Waddell Citation2016), and these authors suggest that an early operation (within <24 h) is appropriate in relatively healthy patients. In patients with substantial comorbidities, they concluded that a delay (of up to 5 days) is acceptable and will not affect mortality if the general condition of the patient can be optimized in the meantime. In this context, the Sernbo score appears to be a valuable tool for identification of patients at risk—and those in need of detailed preoperative optimization and intensified postoperative rehabilitation.

Current care of displaced FNF patients at our hospital involves a fast-track system in which the Sernbo score can easily be evaluated by the orthopedic surgeon on call or by non-specialized caregivers. The Sernbo score seems amendable to stratification into 3 rather distinct categories with statistically significantly different mortality rates, which might further facilitate its use in clinical practice. It was also anticipated that the score would guide surgeons in their choice of surgical treatment in the high- and low-risk groups. We included patients treated with both THA and HA to gain access to the whole population of patients with displaced FNFs who were eligible for arthroplasty. The choice between THA and HA was guided by the patient’s biological age, estimated remaining lifetime, and activity level (Rogmark and Leonardsson Citation2016). Even though THA means more extensive surgery and higher perioperative risk, the effect on mortality rate in our study was small, as also shown in a meta-analysis (Yu et al. Citation2012). Thus, our results do not aid in decision making between HA and THA, but a 1-year mortality may be too short to be fully relevant in this regard. Perhaps future studies with longer follow-up may provide better discriminative information. On the other hand, it can be argued that the operative trauma of adding an acetabular component perhaps does not influence mortality, and might in fact lead to less pain and better function postoperatively. Clearly, the optimal choice between HA and THA in the elderly and frail requires further evaluation.

Our findings partially corroborate the findings of Dawe et al. (Citation2013), who found the Sernbo score to be the only predictor of mortality (AUC =0.71, 95% CI: 0.65–0.76) with a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 51%. However, Dawe et al. presented 30-day mortality as endpoint, and our study suggests that the predictive ability of the score is maintained—or perhaps even slightly better—at 1-year. Our opinion is that these data add to its clinical value and merit further use of the score. A review by Karres et al. (Citation2015) investigating 6 models for prediction of 30-day or 1-year mortality included the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), the orthopedic physiologic and operative severity score for the enumeration of mortality and morbidity (O-POSSUM), estimation of physiological ability and surgical stress (E-PASS), and the Nottingham hip fracture score (NHFS)—the latter 3 being specifically designed for hip fractures. All the models except O-POSSUM had an AUC of greater than 0.7, demonstrating fair discriminative power, but none gave good or excellent discrimination. In contrast to these scoring systems, the Sernbo score is much less complex and uses simple variables that are often available in the emergency setting. The present study achieved a fair degree of predictive ability (AUC =0.79), which indicates that the Sernbo score appears to be valid and at least on a par with other instruments in the literature (Takawira et al. Citation2015).

Several factors affect 1-year mortality in this patient group, such as age, cognitive impairment (Söderqvist et al. Citation2009, Stewart et al. Citation2011, Baker et al. Citation2011, Hu et al. Citation2012), the patient’s pre-fracture living conditions (Holvik et al. Citation2010, Alzahrani et al. Citation2010, Stewart et al. Citation2011, Hu et al. Citation2012), and undoubtedly their previous mobility. A higher score on the "mini mental test" and female sex has been shown to be associated with increased survival rates (Bretherton and Parker Citation2015). The Sernbo score covers all these observations, and the ROC analyses indicated that all of its 4 inherent aspects were needed in conjunction to accurately predict mortality. In our opinion, perhaps the only aspect missing in the Sernbo score is a strictly medical comorbidity item. We could not, however, identify the ASA score as a predictor, in contrast to previous studies (Bretherton and Parker Citation2015). There are, of course, many other factors that can confound the results, which we have not taken into account. One example is length of hospital stay (Nordström et al. Citation2015), especially in patients who are discharged early to a short-term nursing home (Nordström et al. Citation2016), where the risk of complications is higher (Ellis et al. Citation2011, Grigoryan et al. Citation2014) and where rehabilitation facilities are less developed (Hollingworth et al. Citation1993).

The main limitation of the present study is its single-center, observational design—where several confounders may have been either overlooked or underestimated due to type-II error. There was selection bias also, of course, in that the study was conducted using FNF patients who were already eligible for any type of hip arthroplasty surgery. The strength of the study is its prospective design, with none of the patients lost to follow-up. Future, larger studies will show whether this scoring system is useful at the national level, including also patients with trochanteric fractures.

In summary, patients with a Sernbo score graded as high-risk were approximately 15 times more likely to die during the first year after a hip fracture than those in the low-risk group. This easy-to-use scoring system could be used to direct preoperative management and plan multidisciplinary postoperative care in high-risk patients when they are admitted.

Supplementary data

Figure 1 and Tables 4 and 6 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1318628.

CM followed up patients, collected data, and wrote the manuscript. TE performed the statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. JB followed up patients and collected data. CB and PM reviewed the manuscript. SM initiated the study, operated patients, collected data, performed the statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

We thank Professor Anders Odén for statistical advice. We also thank research nurses Lotta Söderlind, Helene Sörell, and Elieann Broman for their outstanding work during the study.

IORT_A_1318628_SUPP.PDF

Download PDF (212.1 KB)- Abrahamsen B, van Staa T, Ariely R, Olson M, Cooper C. Excess mortality following hip fracture: a systematic epidemiological review. Osteoporos Int 2009; 20(10): 1633–50.

- Alzahrani K, Gandhi R, Davis A, Mahomed N. In-hospital mortality following hip fracture care in southern Ontario. Can J Surg 2010; 53: 294–8.

- Baker N L, Cook M N, Arrighi H M, Bullock R. Hip fracture risk and subsequent mortality among Alzheimer’s disease patients in the United Kingdom, 1988–2007. Age Ageing 2011; 40: 49–54.

- Bretherton C P, Parker M J. Early surgery for patients with a fracture of the hip decreases 30-day mortality. Bone Joint J 2015; 97-B(1): 104–8.

- Dawe E J, Lindisfarne E, Singh T, McFadyen I, Stott P. Sernbo score predicts survival after intracapsular hip fracture in the elderly. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2013; 95(1): 29–33.

- Ellis G, Whitehead MA, Robinson D, O’Neill D, Langhorne P. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011; 343: d6553.

- Grigoryan K V, Javedan H, Rudolph J L. Orthogeriatric care models and outcomes in hip fracture patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma 2014; 28(3): 49–55.

- Hardinge K. The direct lateral approach to the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1982; 64(1): 17–9.

- Hollingworth W, Todd C, Parker M, Roberts J A, Williams R. Cost analysis of early discharge after hip fracture. BMJ 1993; 307: 903–6.

- Holvik K, Ranhoff A H, Martinsen M I, Solheim L F. Predictors of mortality in older hip fracture inpatients admitted to an orthogeriatric unit in Oslo, Norway. J Aging Health 2010; 22(8): 1114–31.

- Hu F, Jiang C, Shen J, Tang P, Wang Y. Preoperative predictors for mortality following hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury 2012; 43: 676–85.

- Karres J, Heesakkers N, Ultee J, Vrouenraets B. Predicting 30-day mortality following hip fracture surgery: Evaluation of six risk prediction models. Injury 2015; 46(2): 371–7.

- Kirkland L L, Kashiwagi D T, Burton M C, Cha S, Varkey P. The Charlson Comorbidity Index score as a predictor of 30-day mortality after hip fracture surgery. Am J Med Qual 2011; 26(6): 461–7.

- Leonardsson O, Sernbo I, Carlsson A, Akesson K, Rogmark C. Long-term follow-up of replacement compared with internal fixation for displaced femoral neck fractures: results at ten years in a randomised study of 450 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92(3): 406–12.

- Lewis P M, Waddell J P. When is the ideal time to operate on a patient with a fracture of the hip?: a review of the available literature. Bone Joint J 2016; 98-B(12): 1573–81.

- Mohamed K, Copeland G P, Boot D A, Casserley H C, Shackleford I M, Sherry P G, Stewart G J. An assessment of the POSSUM system in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84(5): 735–9.

- Moore A T. The self-locking metal hip prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1957; 39 (4): 811–27.

- Nordström P, Gustafson Y, Michaëlsson K, Nordström A. Length of hospital stay after hip fracture and short term risk of death after discharge: a total cohort study in Sweden. BMJ 2015; 350: h696.

- Nordström P, Michaëlsson K, Hommel A, Norrman P O, Thorngren K G, Nordström A. Geriatric rehabilitation and discharge location after hip fracture in relation to the risks of death and readmission. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016; 17(1): 91. e1–7.

- Rogmark C, Leonardsson O. Hip arthroplasty for the treatment of displaced fractures of the femoral neck in elderly patients. Bone Joint J 2016; 98-B(3): 291–7.

- Rosengren B E, Björk J, Cooper C, Abrahamsen B. Recent hip fracture trends in Sweden and Denmark with age-period-cohort effects. Osteoporos Int 2017; 28(1): 139–49.

- Stewart NA, Chantrey J, Blankley SJ, Boulton C, Moran CG. Predictors of 5 year survival following hip fracture. Injury 2011; 42: 707–713.

- Söderqvist A, Ekström W, Ponzer S, Pettersson H, Cederholm T, Dalén N, Hedström M, Tidermark J; Stockholm Hip Fracture Group. Prediction of mortality in elderly patients with hip fractures: a two-year prospective study of 1,944 patients. Gerontology 2009; 55(5): 496–504.

- Takawira C, Marufu, Mannings A, Moppett I K. Risk scoring models for predicting peri-operative morbidity and mortality in people with fragility hip fractures: Qualitative systematic review. Injury 2015; 46(12): 2325–34.

- van Zeeland M L, Genovesi I P, Mulder J W, Strating P R, Glas A S, Engel A F. POSSUM predicts hospital mortality and long-term survival in patients with hip fractures. J Trauma 2011; 70(4): 67–72.

- Wiles M D, Moran C G, Sahota O, Moppett I K. Nottingham Hip Fracture Score as a predictor of one year mortality in patients undergoing surgical repair of fractured neck of femur. Br J Anaesth 2011; 106: 501-4.

- Yu L, Wang Y, Chen J. Total hip arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures: meta-analysis of randomized trials. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012; 470(8): 2235–43.