Abstract

Background and purpose — 7% of the asymptomatic population has leg-length inequality (LLI) greater than 12 mm. It has been proposed that LLI of >5 mm can be associated with an increased risk of osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee and hip. We studied a possible association between LLI and OA of the knee and hip joint.

Patients and methods — We followed 193 individuals (97 women, 96 men) for 29 years. The initial mean age of the participants was 43 (34–54) years, and they had no clinical histories or signs of leg symptoms. The initial standing radiographs of their hips were re-examined and measured for LLI and signs of OA. None had any signs of OA. At the follow-up, data on performed hip or knee arthroplasties were obtained.

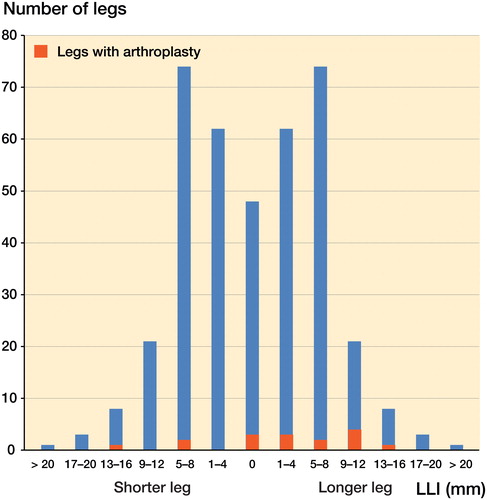

Results — 24 (12%) of the subjects had no discernible leg-length difference, 62 (32%), had LLIs of 1–4 mm, 74 (38%) of 5–8 mm, 21 (11%) of 9–12 mm, and 12 (6%) of over 12 mm. 16 (8%) of the subjects had undergone arthroplasty for primary OA during follow-up, and of those, 8 for both hip and knee OA. 10 individuals had undergone an arthroplasty of the longer leg and only 3 of the shorter leg. In the group of equal leg length, 3 had had an arthroplasty of hip or knee.

Interpretation — We noted that hip or knee arthroplasty due to primary OA had been done 3 times more often to the longer leg than to the shorter.

The incidence of leg-length inequality (LLI) in the normal population may be as high as 60–70% (Woerman and Binder-Macleod Citation1984), and 7% of the asymptomatic population has an LLI greater than 12 mm (Gofton and Trueman Citation1971). It has also been found that chronic hip pain and osteoarthritis occur more often on the side of the longer extremity (Friberg Citation1983). The prevalence and severity of knee OA have been found to be higher in individuals with LLI than without LLI (Rothenberg Citation1988). Murray and Azari (Citation2015) stated, according to their findings in an extensive literature review, that measurements of LLI should be based on radiography examinations. Furthermore, they supported the prevailing theory that even a mild LLI can cause excessive mechanical pressure on joint cartilage and underlying bone, due to a reduced articular joint surface area, and thus may lead to primary OA.

In a large, recent prospective study that used radiographs for LLI measurements, Harvey and coworkers (2010) found that LLIs of 5 mm were associated with an increased prevalence of progressive OA of the knee of the shorter leg. However, Gofton and Trueman (Citation1971) stated that LLI causes tilting of the pelvis and, presumably, a greater heel impact and stress on joints of the longer leg compared with the shorter.

In a study from our hospital, of 100 consecutive hip arthroplasty patients, the preoperative radiographs showed that OA occurred more frequently in the hip of the longer (84%) than in the shorter (16%) leg (Tallroth et al. Citation2005). However, the development of OA did not show a linear relationship with the magnitude of the LLI. As hip OA occurred more frequently in the longer leg, the authors speculated about whether LLI was associated with OA in the hip of the longer leg.

We gained access to unusually extensive radiographic material of 193 asymptomatic middle-aged individuals and their standing hip images taken 29 years ago. Our aim with the present study was to look for the distribution of LLI and to estimate a possible relationship between LLI and later development of OA of the knee and hip joint.

Patients and methods

This study is a continuation of a comprehensive clinical and radiographic evaluation in 1987 on subjects (all Scandinavian Caucasian) who comprised 4 specific occupational and sex groups: they worked for the Helsinki City Council as truck or tractor drivers (men), office or school cleaners (women), or clerks or civil servants (men and women) (Soukka et al. Citation1991). At that time, none of the subjects had suffered from leg pain or disability. That study was approved by the Ethical Committees of the employees and of our Orton Orthopaedic Hospital of the Orton Foundation and the participants gave written informed consent.

Radiographs of the hips were conducted standing in an anteroposterior position (Turula et al. Citation1985). Vertical reference lines were obtained on the radiographs using a plumb line. The radiation doses were minimized by having a small field of view and a sensitive screen-film combination. The LLI was measured by a musculoskeletal radiologist (KT) as the difference in height between the vertices of the femoral heads (). The measurements on the radiographs were adjusted with a magnification factor of 0.82, which is a coefficient based on the X-ray tube-to-object distance and the distance from tube to film.

Figure 1. Woman aged 50 years. Standing radiograph with a vertical plumb line shows a 10 mm LLI (black line) and a slight pelvic tilt to the left (white line). A hip arthroplasty was performed on the longer leg 27 years later.

29 years later, the radiographs of 193 subjects (97 women, 96 men) were collected from the archives. At re-examination of the index hip radiographs, none of the patients showed signs of OA, such as a joint width less than 2 mm or presence of reactive sclerosis, osteophytes, or subarticular cysts. The measured LLIs were classified into 7 subgroups: 0, 1–4, 5–8, 9–12, 13–16, 17–20, and 21+ mm to facilitate analysis. Information on performed arthroplasties was obtained from the Finnish Registry of Arthroplasty (approval identification number Dnro THL/784/5.05.00/2015). This is a mandatory, nationwide registry administered by the Finnish National Institute for Health and Welfare to gather information about arthroplasties performed since 1980 (Seppänen et al. Citation2016).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Pearson’s chi-square statistics were applied to determine statistically significant differences in distributions between the patients with or without arthroplasty. An independent-samples Student’s t-test was used to assess the equality of variances of the calculated subgroups such as sex or patients with or without arthroplasty. The statistically significant threshold was set at p ≤ 0.05 (2-tailed).

Results

The mean age of the 193 participants was 72 (63–83) years at the follow-up (). 24 (12%) of the subjects had equal leg length. Nearly 40% (74) of the subjects had 5–8 mm of LLI and 15% (29) ≥ 10 mm. The largest LLI was 26 mm. There was no statistically significant difference between men and women concerning LLI (5.2 vs. 5.4, p = 0.81). The distribution of LLIs is shown in .

Figure 2. Relationship of arthroplasties and LLI. Left of center (0) is the shorter leg, and to the right is the longer leg. The blue columns show legs in different LLI categories. The red columns show the number of performed arthroplasties in each category. 10 of the operations were carried out on the longer leg.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study group

16 (8%) of the patients had had a total knee or hip arthroplasty due to primary OA during the follow-up, 8 in the hip and 8 in the knee (). 11 of the 16 operated patients were women. 7 of 16 operated patients had undergone 2 primary arthroplasties during follow-up. 1 of the operated patients had had bilateral hip arthroplasties. The first arthroplasty was done, on average, 16 (5–17) years after 1987, when the index radiographs were taken, and the second arthroplasties were done a mean 2.7 (0–8) years after the first arthroplasty.

Table 2. Individual information on leg-length inequality (LLI) and knee and hip arthroplasties

3 of the 16 arthroplasties had been done on patients with equal leg length (). Arthroplasty was done to the shorter leg in 3/16 of the patients and to the longer leg in 10/16; thus, arthroplasty was done 3 times as often in the longer leg as in the shorter leg.

Discussion

6% of our patients had an LLI of more than 12 mm, which is close to the value reported earlier by Gofton and Trueman (Citation1971). In another study by Harvey et al. (Citation2010), 5% of their group had an LLI of 10 mm or more, while in our study the corresponding fraction was 15%. An LLI ≥2 cm was seen in our study in only 2 cases. We found that the longer leg was more often affected by OA.

According to the Knee and Hip Osteoarthritis Finnish Current Guidelines (Citation2012), 32% of women and 16% of men over 75 years old have knee OA, and 1 out of 5 over 75 years old have hip OA; the incidences increase with age. The risks for hip and knee OA are multifaceted and are influenced by genetics, repeating micro-traumas, and physical stress, as well as anatomical variations. In a large population-based survey of 3,620 individuals, Gosvig et al. (Citation2010) investigated the prevalence of malformations in acetabulae and femoral heads and the risk of hip joint OA, and found that a deep acetabular socket and a pistol-grip deformity of the femoral head were associated with an increased risk of hip OA. Our study, on the other hand, focused solely on LLI as a risk factor of OA.

In our study, there were no statistically significant differences between men and women in regards to LLI. However, two-thirds of subjects who had arthroplasty during the follow-up were women. According to a systematic review by Singh (Citation2011), several studies corroborate this finding. In Sweden, the rate of knee arthroplasties is twice as high in women as in men (Robertsson et al. Citation2000), and a similar sex difference has also been reported from the United States (Jain et al. Citation2005).

Most arthroplasties are done on 60- to 80-year-old patients. On average, our subjects were 72 years old, which makes it likely that more arthroplasties will be done in this group during the next 10 years. If we had had new radiographs at follow-up, it would have been possible to compare the differences in joint conditions between baseline and follow-up in order to check whether any had developed signs of OA and whether this finding was more prominent in the longer or shorter limb. According to a study by Harvey et al. (Citation2010), LLIs ≥1 cm were associated with radiographic and symptomatic knee OA in the shorter limb. However, our results suggest that OA will develop and arthroplasty will be performed earlier in the knee and hip joints of the longer leg.

An LLI generally causes a pelvic tilt, which leads to a smaller load-bearing articular surface in the hip joint (Gofton and Trueman Citation1971). The concomitant greater pressure per articular unit has been thought to promote OA in the hip of the longer leg (Gofton and Trueman Citation1971, Clarke Citation1972). Both a stronger impact and smaller center-edge angle expose the hip joint to an increased mechanical cartilage load (Bhave et al. Citation1999).

Hip pain is more common on the side of the longer leg (Friberg Citation1983). The correlation between LLI and hip OA of the longer leg was detected in the 1960s (Harvey et al. Citation2010). However, Noll (Citation2013) found in his observational study that osteoarthritic knee pain was more common in the apparent short leg. Individuals are often unaware of LLI and suffer no symptoms for a considerable time. If LLI is detected it is easily corrected using shoe modifications by raising one heel and lowering the other, which brings up the intriguing possibility that correction of LLI is a simple and cost-effective method of treatment and prevention of leg OA. This has been verified in several studies in which a simple shoe lift can equalize the lengths of the limbs and thus provide symptomatic relief for patients with hip and low back pain in association with LLI (Friberg Citation1983, Rothenberg Citation1988, Bhave et al. Citation1999).

Many clinical disorders like OA of knee and hip, low back pain, and lumbar scoliosis have been associated with LLI. In many investigations, the magnitude of LLI has been divided into groups to provide guidelines for the choice of treatment. Analyzing our results of LLI dichotomously into 2 subgroups, 0–9 mm and 10 mm and greater, there were 164 individuals (85%) in the first group and 29 (15%) in the second. Arthroplasties were performed 3 times (p = 0.06) more frequently in those with LLIs of 10 mm or greater than in the other group. A similar correlation with the degree of LLI and the side of hip and sciatic pain has been reported by Friberg (Citation1983).

There are some limitations to our study. First, no knee radiographs were taken at the time of the primary index examinations. Second, we lack information concerning height, comorbidities, sports activities, and possible knee or hip problems during the follow-up time aside from the known arthroplasties for primary OA of the hip or knee. A final limitation in our 29-year follow-up of these healthy middle-aged adults was the surprisingly low incidence of OA, which obviously depended on the end point of the follow-up. Only those with a serious degree of OA had required an arthroplasty. This is likely the reason for the low occurrence of discovered OA, which hindered proper statistical validations. Even with these limitations, our results show that there were 3 times as many arthroplasties carried out on the longer extremity as on the shorter. We suggest that further research studies on long-term follow-up of LLI and occurrence of OA should be performed with the same comparable baseline and follow-up imaging with radiation-free MRIs to determine the incidence of the grades of OA at the time of follow-up.

KT drafted the manuscript. LR managed and analyzed the data. All authors were responsible for the design of the study, interpretation of the data, and final approval of the manuscript.

- Bhave A, Paley D, Herzenberg J E. Improvement in gait parameters after lengthening for the treatment of limb-length discrepancy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1999; 81 (4): 529–34.

- Friberg O. Clinical symptoms and biomechanics of lumbar spine and hip joint in leg length inequality. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1983: 8 (6): 643–51.

- Clarke G R. Unequal leg length: An accurate method of detection and some clinical results. Rheumatol Phys Med 1972; 11 (8): 385–90.

- Gofton J P, Trueman G E. Studies in osteoarthritis of the hip, II: Osteoarthritis of the hip and leg-length disparity. Can Med Assoc J 1971; 104 (9): 791–9.

- Gosvig K K, Jacobsen S, Sonne-Holm S, Palm H, Troelsen A. Prevalence of malformations of the hip joint and their relationship to sex, groin pain, and risk of osteoarthritis: A population-based survey. J Bone Joint Surg 2010; 92-A: 1162–9.

- Harvey W F, Yang M, Cooke T D, Segal N A, Lane N, Lewis C E, Felson D T. Association of leg-length inequality with knee osteoarthritis: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2010; 152 (5): 287–95.

- Jain N B, Higgins L D, Ozumba D, Guller U, Cronin M, Pietrobon R, Katz J N. Trends in epidemiology of knee arthroplasty in the United States, 1990–2000. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52 (12): 3928–33.

- Knee and hip osteoarthritis (online). Current Care Guidelines. Working group appointed by the Finnish Medical Society Duodecim and the Finnish Orthopaedic Association.Helsinki: The Finnish Medical Society Duodecim, 2012 (referred November 19, 2016). Available online at: www.kaypahoito.fi

- Murray K J, Azari M F. Leg length discrepancy and osteoarthritis in the knee, hip and lumbar spine. J Can Chiropr Assoc 2015; 59 (3): 226–37.

- Noll D R. Leg length discrepancy and osteoarthritic knee pain in the elderly: An observational study. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2013; 113 (9): 670–8.

- Robertsson O, Dunbar M J, Knutson K, Lidgren L. Past incidence and future demand for knee arthroplasty in Sweden: A report from the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register regarding the effect of past and future population changes on the number of arthroplasties performed. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71 (4): 376–80.

- Rothenberg R. Rheumatic disease aspects of leg length inequality. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1988; 17 (3): 196–205.

- Seppänen M, Karvonen M, Virolainen P, Remes V, Pulkkinen P, Eskelinen A, Liukas A, Mäkelä K T. Poor 10-year survivorship of hip resurfacing arthroplasty: 5,098 replacements from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2016; 87 (6): 554–9.

- Singh J A. Epidemiology of knee and hip arthroplasty: A systematic review. Open Orthop J 2011; 16 (5): 80–5.

- Soukka A, Alaranta H, Tallroth K, Heliövaara M. Leg-length inequality in people of working age: The association between mild inequality and low-back pain is questionable. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1991; 16 (4): 429–31.

- Tallroth K, Ylikoski M, Lamminen H, Ruohonen K. Preoperative leg-length inequality and hip osteoarthrosis: A radiographic study of 100 consecutive arthroplasty patients. Skeletal Radiol 2005; 34 (3): 136–9.

- Turula K B, Friberg O, Haajanen J, Lindholm T S, Tallroth K. Weight-bearing radiography in total hip replacement. Skeletal Radiol 1985; 14 (3): 200–4.

- Woerman A L, Binder-Macleod S A. Leg length discrepancy assessment: Accuracy and precision in five clinical methods of evaluation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1984; 5 (5): 230–9.