Abstract

Background and purpose — The original Müller acetabular reinforcement ring (ARR) was developed to be used for acetabular revisions with small cavitary and/or segmental defects or poor acetabular bone quality. Long-term data for this device are scarce. We therefore investigated long-term survival and radiographic outcome for revision total hip arthroplasty using the ARR.

Patients and methods — Between October 1984 and December 2005, 259 primary acetabular revisions using an ARR were performed in 245 patients (259 hips). The mean follow-up time was 10 (0–27) years; 8 hips were lost to follow-up. The cumulative incidence for revision was calculated using a competing risk model. Radiographic assessment was performed for 90 hips with minimum 10 years’ follow-up. It included evaluation of osteolysis, migration and loosening.

Results — 16 ARRs were re-revised: 8 for aseptic loosening, 6 for infection, 1 for suspected infection, and 1 due to malpositioning of the cup. The cumulative re-revision rate for aseptic loosening of the ARR at 20 years was 3.7% (95% CI 1.7–6.8%). Assuming all patients lost to follow-up were revised for aseptic loosening, the re-revision rate at 20 years was 6.9% (95% CI 4.1–11%). The overall re-revision rate of the ARR for any reason at 20 years was 7.0% (95% CI 4.1–11%). 21 (23%) of the 90 radiographically examined ARR had radiographic changes: 12 showed isolated signs of osteolysis but were not loose; 9 were determined loose on follow-up, of which 5 were revised.

Interpretation — Our data suggest that the long-term survival and radiographic results of the ARR in primary acetabular revision are excellent.

Revision total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a continuously increasing procedure. One of the major challenges surgeons are faced with is the reduced quantity and quality of the remaining bone-stock. Numerous techniques as well as different implant designs have been elaborated to address this specific issue (Taylor and Browne Citation2012). In case of segmental bone defects, bulk allografts in combination with a cemented cup or impaction grafting are a reliable but technically demanding option (Slooff et al. Citation1984, Schreurs et al. Citation2009, Garcia-Cimbrelo et al. Citation2010, Ibrahim et al. Citation2013). Trabecular metal buttresses in combination with trabecular metal cups have shown good short-term results (Van Kleunen et al. Citation2009, Ballester Alfaro and Sueiro Fernandez Citation2010, Molicnik et al. Citation2014, Bruggemann et al. Citation2017), however, long-term data for this expensive concept are still lacking. Depending on the extent of acetabular defects, jumbo cups showed good intermediate and long-term results (Wedemeyer et al. Citation2008, von Roth et al. Citation2015). A further implant that has been shown to be reliable in the management of extended acetabular bone defects is the Burch-Schneider anti-protrusio cage (Wachtl et al. Citation2000, Ilchmann et al. Citation2006, Regis et al. Citation2008, Citation2012).

The Müller acetabular reinforcement ring (ARR) was developed for complex primary hip replacements and acetabular revisions with small cavitary and/or segmental defects or when acetabular bone quality is poor (Gill et al. Citation1998). Long-term results for the ARR in primary THA have recently been shown to be excellent (Sirka et al. Citation2016). The ARR has not only been used in primary THA, but also for revision THA in the past 3 to 4 decades, especially in Central Europe, with varying results () (Schatzker et al. Citation1984, Haentjens et al. Citation1986, Rosson and Schatzker Citation1992, Gill et al. Citation1998, Schlegel et al. Citation2006, Bruggemann et al. Citation2017). The aim of this study was to present long-term survival and radiographic outcome of revision THA, using the ARR in patients with small cavitary and/or segmental acetabular defects.

Table 1. Comparison of different studies concerning revision ARR (including Ganz ring) survival

Patients and methods

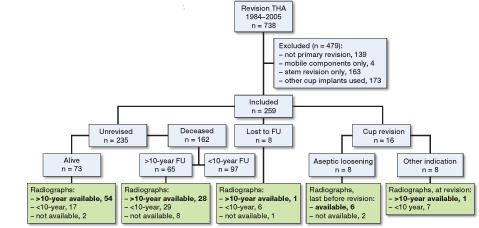

Between October 1984 and December 2005 738 THA were revised at our institution; 432 of them had a primary cup revision. In 95 cases an anti-protrusio cage (Burch-Schneider), in 11 cases a cemented PE cup, and in 67 various other primary cups were used. In the remaining 259 hips (245 patients), revision with an ARR was performed (). The median age at the time of the revision was 72 (31–91) years. 144 patients (153 hips, 59%) were male. The specific indications for the index operation are summarized in . Patients had a prospective clinical and radiographic follow-up according to our in-house standard; examinations were scheduled at 3 months, 1, 2, 5, and every 5 years after surgery. Patients’ death date was obtained from the regional death register database. In the case of a missing regular follow-up, the patient was contacted by telephone to ensure that the implant was still in situ.

Table 2. Indication for revision THA

Implants

The ARR (Zimmer, Winterthur, Switzerland) covers four-fifths of the hemisphere (); its design remained unchanged during the whole study period (Ochsner Citation2003). Until January 1987 implants were made of stainless steel; thereafter they were made of titanium with 3 different surface roughnesses () (Sirka et al. Citation2016). 240 all-PE cups (Müller low-profile, Zimmer, Winterthur, Switzerland) and 19 PE cups with a metal bearing surface (Metasul low profile, Zimmer, Winterthur, Switzerland) were cemented inside the ARR. For all revision operations Palacos R + G cement (Heraeus, Hanau, Germany) was used. Additional stem revision was performed in 176 cases using various cemented and uncemented stems ().

Figure 2. The ARR covers four-fifths of a hemisphere and the design remained unchanged during the whole study period.

Table 3. Implant specifications

Surgical technique

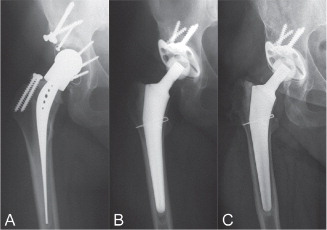

All patients were operated in a supine position via a Hardinge approach or an extended trochanteric osteotomy (Bircher et al. Citation2001), according to the surgeon’s preference. If extended defects (AAOS 4 and 5) (D’Antonio et al. Citation1989) were encountered intraoperatively or where no fixation was possible, an anti-protrusio cage (Burch-Schneider) instead of an ARR was used. In cases where an ARR was inserted into the acetabulum, primary press-fit with firm contact to host bone was aimed for. Caution was taken to ensure that the center of the hip was placed at its original place or—in case of too much bone loss—somewhat more cranial but on the connecting line between the anatomic center of the hip and the center of the iliosacral joint. The ARR was additionally fixed using 2–5 cancellous bone screws oriented in the direction of the iliosacral joint (). Steel screws were chosen to fix the ARRs made of steel and, likewise, titanium screws were used to fix the ARRs made of titanium. In case of bone defects, either autologous (removed ossifications during approach or acetabular bone from reaming) or allogenic morselized bone grafts were used to fill preexisting cavitary defects. Finally, the PE cups were fixed in the ARR with cement using hand-mixed, high-viscosity bone cement (Palacos R + G) without the use of a jet-lavage or pressurizing prior to insertion of the cup. Postoperatively, patients were mobilized with full-weight bearing as tolerated from the first postoperative day using 2 crutches.

Figure 3. Case description. A 44-year-old female patient with aseptic loosening of the primary THA 5 years after implantation for developmental dysplasia of the hip with an acetabular shelf graft. (A) Intraoperative defect size AAOS 0, no additional bone grafting (A), postoperative (B) and 25 years after revision (C).

Radiographic follow-up

Standardized anterior–posterior (ap) views centered on the symphysis, showing the entire prosthesis, were taken at each follow-up. For detailed radiographic follow-up, all available radiographs of unrevised patients with follow-up of >10 years (n = 83) or patients with a re-revision of the ARR (n = 7) were analyzed. The last radiograph prior to the index operation and the first radiograph in the immediate postoperative period, as well as the radiograph taken at the last follow-up, were investigated ().

All radiographs were analyzed using DICOM software (Agfa IMPAX v6.5.3.117; Agfa HealthCare, Mortsel, Belgium). Measurements were performed using AGFA-Orthopaedic-Tools (AGFA-Orthopaedic-Tools Version 2.10 (Build 4); Agfa HealthCare N.V., Mortsel, Belgium). Radiographs were calibrated with the known true femoral head size.

Preoperative acetabular defects were classified using the system of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (D’Antonio et al. Citation1989). Postoperatively, the radiographs were analyzed for osteolysis, signs of loosening, and migration. Signs of loosening and osteolysis were analyzed on both the acetabular and the femoral side; migration was analyzed only on the acetabular side.

Osteolysis around the ARR was defined as being radiographic appearance of bone resorption ≥2 mm in the 3 zones described by DeLee and Charnley (Citation1976), which was not evident on the first postoperative radiograph (Zicat et al. Citation1995). The ARR was classified as loose if there was breakage of more than 50% of the screws or if a complete progressive radiolucent line was present around the cup and/or more than 50% of the screws (Sirka et al. Citation2016). To further identify loosening, migration of the ARR was measured. This was done by measuring the vertical displacement of the center of the cup relative to the inter-teardrop line or horizontal displacement of the cup center relative to the ipsilateral teardrop line (Nunn et al. Citation1989). Finally, a change in the inclination angle of the cup of more than 4° and a change of vertical and/or of horizontal position >3 mm were taken as evidence of a loose cup (Joshi et al. Citation1998).

Osteointegration of allografts was analyzed and considered as present when there was evidence of trabecular bridging of the host–graft interface, return of graft density to normal (Azuma et al. Citation1994) and no evidence of fragmentation or radiolucent lines (Morsi et al. Citation1996). A clear reduction in density or breakdown of the transplanted bone was defined as bone resorption (Kondo and Nagaya Citation1993).

Statistics

In 14 patients with bilateral surgeries, both hips were included in the analyses (Robertsson and Ranstam Citation2003, Lie et al. Citation2004). A survival analysis of the ARR with death as a competing risk and various endpoints was performed to determine the cumulative revision rate (CRR): (i) aseptic loosening of the ARR, (ii) worst-case scenario, assuming that all ARR lost to follow-up had been revised for aseptic loosening at the date of the last contact, and (iii) revision of the ARR for any reason. There was no exchange of the PE alone in this series of patients. The time to revision was calculated as the time between the date of implantation and the date of revision. Patients without any revision were censored at the date of last contact. 95% confidence intervals (CI) are given. Data are presented with median (range). SPSS® software version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) and R statistical package version 3.1.3 (R Core Team Citation2015) were used for all statistical analysis.

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

Ethical approval for this study was obtained by the local ethical committee (2016-00559).

No external funding was received.

No competing interests were declared.

Results

8 patients were lost to follow-up (3 came from abroad, 3 had moved and could not be traced, and 2 were assumed dead, being >100 years old at the time of analysis) after 5.3 (0–15) years. 155 patients (162 hips) died during follow-up for causes not related to the revision after 8.2 (0–27) years.

At final follow-up, 16 ARRs had been re-revised (). 8 ARRs (1 stainless steel, 5 smooth-blasted titanium, and 2 rough-blasted titanium) were re-revised for aseptic loosening after 6.0 (1.5–14) years. 6 ARRs were re-revised for infection after 4.8 (0.5–14) years. 1 ARR was re-revised due to suspected infection after 4.9 years, which was not confirmed through intraoperative samples. A further ARR was re-revised in another hospital after 11 years during a stem revision for isolated aseptic loosening of the stem with the intraoperative finding of a malpositioned cup.

Table 4. Specific data on re-revision of the ARR

Survival analysis

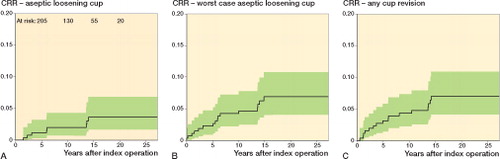

The CRR for aseptic loosening of the ARR at 10 years was 2.0% (CI 0.7–4.3%). At 20 years, the CRR for aseptic loosening was 3.7% (CI 1.7–6.8%) (). In contrast, the competing risk for death at 10 years and 20 years was 40% (CI 34–46%) and 74% (CI 67–80%), respectively.

Figure 4. A. Cumulative revision rate (CRR) with 95% CI of the ARR for aseptic loosening as endpoint. B. Worst-case scenario assuming all patients lost to follow-up revised for aseptic loosening. C. CRR for any cup revision.

A worst-case scenario, assuming that the 8 ARRs lost to follow-up had additionally been revised for aseptic loosening, resulted in a CRR at 20 years of 6.9% (CI 4.1–11%) ().

At 20 years, the overall CRR of the ARR for any reason was 7.0% (CI 4.1–11%) ().

Radiographic analysis

The preoperative defects are classified in .

Table 5. Preoperative defect classification (D’Antonio)

For detailed long-term (> 10-year) radiographic analysis, 90 ARRs (8 bilateral) with a median follow-up period of 12.2 (2.2–27) years were analyzed (, numbers in bold). 69 (77%) had no signs of loosening and 12 showed isolated osteolysis but were not loose. According to the previously determined definition, 9 ARRs were classified as being radiographically loose on follow-up; 5 of them were revised. The remaining 4 radiographically loose ARRs were not revised: 2 of these had at least 3 broken screws and additional vertical migration, but no change in cup inclination, 1 showed signs of osteolysis in 2 zones, and 1 showed an isolated change in cup inclination of more than 8°.

29 of 90 ARRs were implanted without additional bone grafting. For the other 61 cases, a bone graft was used and graft incorporation was rated trabecular (n = 50) or partially sclerotic (n = 9). In 2 cases a graft resorption was observed; both ARRs needed revision due to aseptic loosening.

Discussion

The treatment of acetabular bone defects encountered in revision arthroplasty is discussed controversially. It has been suggested to treat acetabulae with >50% available bone stock by (oversized) spherical press-fit cups (Della Valle et al. Citation2004, Hallstrom et al. Citation2004, Brooks Citation2008). However, with this strategy the acetabulum has to be further reamed, resulting in additional weakening of the anterior and/or posterior column. This bears the risk of larger defects or even pelvic discontinuity in case of re-revision.

In contrast to spherical press-fit cups the ARR covers only 4/5 of the hemisphere. It is flexible and can get an oval deformation during impaction, facilitating press-fit without removal of additional bone anteriorly and/or posteriorly. The orientation of the ARR can be chosen rather liberally and adapted to the existing acetabular bone, resulting in optimal press-fit. Furthermore, the pressure of the ring against the acetabular roof is enhanced and secured by the screws. Additionally, angular stability of the screws is achieved by locking the screw heads with the cement used to fix the cup (Laflamme et al. Citation2008).

Segmental or cavitary defects can be augmented optionally by either morselized auto- or allografts. This is comparable to impaction bone grafting, which contributes to the conservation or restoration of the bone stock. The orientation of the PE cup can be optimized independent of the ARR orientation, which might explain the low re-revision rate due to dislocation when compared with revisions using spherical press-fit cups (Bruggemann et al. Citation2017). Disadvantages of the ARR might be the longer time of operation (Bruggemann et al. Citation2017) and the use of screws that can perforate the bone and cause complications (Ochsner Citation2003, Rue et al. Citation2004).

In some of the cases in our series with minor bone defects, a primary press-fit cup could have been an alternative. However, in our institution, the ARR was used in both primary and revision THA, supported by the excellent survival of the ARR in primary THA (Sirka et al. Citation2016). Superior to the previously published data, this study suggests that long-term survival (20 years) for the ARR in primary revision is excellent, with a CRR of 6.2% for aseptic loosening and 11% for revision for any reason as endpoint.

We used the ARR only with viable host bone and sufficient primary press-fit. If this press-fit could not be achieved or the ARR could not be placed with correct anatomic hip center or somewhat cranial to it and in case of more extended defects (type 4 and 5) we consequently used an anti-protrusio cage (Burch-Schneider). Acetabular defect classification might be slightly different if other classification systems like the Paprosky system (Paprosky et al. Citation1994) had been used, and some of the cases treated with an anti-protrusio cage might have been suitable for the use of an ARR too. Anyhow, the decision for using the ARR instead of an anti-protrusio cage was not mainly based on radiographic findings but on the above-mentioned criteria. Therefore strict patient selection might in part explain the superior survival data as compared with other studies ().

In our series there were 4 radiographically loose ARRs that were not revised. 2 of them showed broken screws without detectable migration or osteolysis around the implant. Angular stability of the screws is achieved by locking the screw heads with the cement used to fix the PE cup (Laflamme et al. Citation2008). Micro-motions of a well-fixed ring can cause oscillating forces on the screws through the locking mechanism and may lead to breakage, which may be wrongly classified as loosening (Sirka et al. Citation2016). Other radiographic changes around the ARR were rare and comparable to the use of the ARR in primary THA (Sirka et al. Citation2016). Thus the risk of pending failure of the remaining ARRs seems small.

Concerning defect classification 23% of the hips could not be classified, which might be considered as a limitation of our study. As there were only 8 revisions for aseptic loosening and these cases were not related to more extended defects our results are excellent, even if assuming that all unclassified defects had been grade 0.

In the whole cohort, no ARR or PE cup had to be revised for recurrent dislocations. As mentioned earlier, one big advantage of the ARR is that the ring is inserted into the acetabular bone, ensuring optimal stability. The PE cup can then be freely oriented in the ARR, ensuring optimal joint stability. As closed reductions have not been monitored in our register we cannot comment on the absolute dislocation rate.

Treatment for periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) was done according to our well-established algorithm (Zimmerli et al. Citation2004). Only 2 of 59 cases treated for PJI showed a persistence of infection. All PE cups were cemented using Palacos R + G independent from the causative bacteria (Born et al. Citation2016, Ilchmann et al. Citation2016).

155 patients (162 hips) died during the study period, while only 16 ARR were revised. Therefore cumulative incidence functions were used to analyze revision rates (Gooley et al. Citation1999, Schwarzer et al. Citation2001, Ranstam et al. Citation2011).

Another limitation may have been that patients who had died during the follow-up period might have been revised elsewhere before their death. This, however, is rather unlikely, as most of the patients were elderly people who preferred to be treated at their nearby hospital (Sirka et al. Citation2016). Of the 8 patients who were lost to follow-up, 6 patients live abroad and could not be traced. Even in the worst-case scenario, rating all hips that were lost to follow-up as having been revised for aseptic loosening, the CRR of the ARR at 20 years would be 6.9 (95% CI 4.1–11%), which can be considered as excellent.

In summary, these data suggest that primary cup revision with the ARR showed excellent outcome, regarding long-term survival and radiographic results. This was achieved, amongst other reasons, by following strict rules in the implantation technique and limiting the use of the ARR to cases where direct contact with the existent bone is possible.

PMG: radiographic analysis, writing of the manuscript; IM: clinical data preparation, data analysis, writing of the manuscript; PEO: study design, writing of the manuscript; TI: writing of the manuscript; LZ: data analysis, preparation of illustrations, writing of the manuscript; MC: idea, design, and planning of study, data analysis, writing of manuscript.

Acta thanks Anders Brüggemann and Anders Enocson for help with peer review of this study.

- Azuma T, Yasuda H, Okagaki K, Sakai K. Compressed allograft chips for acetabular reconstruction in revision hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1994; 76 (5): 740–4.

- Ballester Alfaro J J, Sueiro Fernandez J. Trabecular metal buttress augment and the trabecular metal cup-cage construct in revision hip arthroplasty for severe acetabular bone loss and pelvic discontinuity. Hip Int 2010; 20 (Suppl 7): 119–27.

- Bircher H P, Riede U, Luem M, Ochsner P E. [The value of the Wagner SL revision prosthesis for bridging large femoral defects]. Orthopade 2001; 30 (5): 294–303.

- Born P, Ilchmann T, Zimmerli W, Zwicky L, Graber P, Ochsner P E, Clauss M. Eradication of infection, survival, and radiological results of uncemented revision stems in infected total hip arthroplasties. Acta Orthop 2016: 87(6): 637–43.

- Brooks P J. The jumbo cup: The 95% solution. Orthopedics 2008; 31 (9): 913–15.

- Bruggemann A, Fredlund E, Mallmin H, Hailer N P. Are porous tantalum cups superior to conventional reinforcement rings? Acta Orthop 2017; 88 (1): 35–40.

- D’Antonio J A, Capello W N, Borden L S, Bargar W L, Bierbaum B F, Boettcher W G, Steinberg M E, Stulberg S D, Wedge J H. Classification and management of acetabular abnormalities in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989; (243): 126–37.

- DeLee J G, Charnley J. Radiological demarcation of cemented sockets in total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1976; (121): 20–32.

- Della Valle C J, Berger R A, Rosenberg A G, Galante J O. Cementless acetabular reconstruction in revision total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; (420): 96–100.

- Garcia-Cimbrelo E, Cruz-Pardos A, Garcia-Rey E, Ortega-Chamarro J. The survival and fate of acetabular reconstruction with impaction grafting for large defects. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468 (12): 3304–13.

- Gill T J, Sledge J B, Muller M E. Total hip arthroplasty with use of an acetabular reinforcement ring in patients who have congenital dysplasia of the hip: Results at five to fifteen years. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998; 80 (7): 969–79.

- Gooley T A, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer B E. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: New representations of old estimators. Stat Med 1999; 18 (6): 695–706.

- Haentjens P, Handelberg F, Casteleyn P P, Opdecam P. Experience with the Muller acetabular roof reinforcement ring in conventional and in revision arthroplasty of the hip. Acta Orthop Belg 1986; 52 (3): 344–7.

- Hallstrom B R, Golladay G J, Vittetoe D A, Harris W H. Cementless acetabular revision with the Harris-Galante porous prosthesis: Results after a minimum of ten years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004; 86-A (5): 1007–11.

- Ibrahim M S, Raja S, Haddad F S. Acetabular impaction bone grafting in total hip replacement. Bone Joint J 2013; 95-B (11 Suppl A): 98–102.

- Ilchmann T, Gelzer J P, Winter E, Weise K. Acetabular reconstruction with the Burch-Schneider ring: An EBRA analysis of 40 cup revisions. Acta Orthop 2006; 77 (1): 79–86.

- Ilchmann T, Zimmerli W, Ochsner P E, Kessler B, Zwicky L, Graber P, Clauss M. One-stage revision of infected hip arthroplasty: Outcome of 39 consecutive hips. Int Orthop 2016; 40 (5): 913–18.

- Joshi R P, Eftekhar N S, McMahon D J, Nercessian O A. Osteolysis after Charnley primary low-friction arthroplasty: A comparison of two matched paired groups. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1998; 80 (4): 585–90.

- Kondo K, Nagaya I. Bone incorporation of frozen femoral head allograft in revision total hip replacement. Nihon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi 1993; 67 (5): 408–16.

- Korovessis P, Stamatakis M, Baikousis A, Katonis P, Petsinis G. Mueller roof reinforcement rings. Medium-term results. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999; (362): 125-37.

- Kosters C, Schliemann B, Decking D, Simon U, Zurstegge M, Decking J. The Muller acetabular reinforcement ring: Still an option in acetabular revision of Paprosky 2 defects? Long term results after 10 years. Acta Orthop Belg 2015; 81 (2): 257–63.

- Laflamme G Y, Alami G B, Zhim F. Cement as a locking mechanism for screw heads in acetabular revision shells: A biomechanical analysis. Hip Int 2008; 18 (1): 29–34.

- Lie S A, Engesaeter L B, Havelin L I, Gjessing H K, Vollset S E. Dependency issues in survival analyses of 55,782 primary hip replacements from 47,355 patients. Stat Med 2004; 23 (20): 3227–40.

- Molicnik A, Hanc M, Recnik G, Krajnc Z, Rupreht M, Fokter S K. Porous tantalum shells and augments for acetabular cup revisions. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2014; 24 (6): 911–17.

- Morsi E, Garbuz D, Gross A E. Revision total hip arthroplasty with shelf bulk allografts: A long-term follow-up study. J Arthroplasty 1996; 11 (1): 86–90.

- Nunn D, Freeman M A, Hill P F, Evans S J. The measurement of migration of the acetabular component of hip prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1989; 71 (4): 629–31.

- Ochsner P E. Total hip replacement. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2003.

- Paprosky W G, Perona P G, Lawrence J M. Acetabular defect classification and surgical reconstruction in revision arthroplasty: A 6-year follow-up evaluation. J Arthroplasty 1994; 9 (1): 33–44.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing Vienna, Austria, 2015. (http://www.R-project.org/)

- Ranstam J, Karrholm J, Pulkkinen P, Makela K, Espehaug B, Pedersen A B, Mehnert F, Furnes O, group N s. Statistical analysis of arthroplasty data, II: Guidelines. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (3): 258–67.

- Regis D, Magnan B, Sandri A, Bartolozzi P. Long-term results of anti-protrusion cage and massive allografts for the management of periprosthetic acetabular bone loss. J Arthroplasty 2008; 23 (6): 826–32.

- Regis D, Sandri A, Bonetti I, Bortolami O, Bartolozzi P. A minimum of 10-year follow-up of the Burch-Schneider cage and bulk allografts for the revision of pelvic discontinuity. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27 (6): 1057–63 e1.

- Robertsson O, Ranstam J. No bias of ignored bilaterality when analysing the revision risk of knee prostheses: Analysis of a population based sample of 44,590 patients with 55,298 knee prostheses from the national Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2003; 4: 1.

- Rosson J, Schatzker J. The use of reinforcement rings to reconstruct deficient acetabula. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1992; 74 (5): 716–20.

- Rue J P, Inoue N, Mont M A. Current overview of neurovascular structures in hip arthroplasty: Anatomy, preoperative evaluation, approaches, and operative techniques to avoid complications. Orthopedics 2004; 27 (1): 73–81.

- Schatzker J, Glynn M K, Ritter D. A preliminary review of the Muller acetabular and Burch-Schneider antiprotrusio support rings. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1984; 103 (1): 5–12.

- Schlegel U J, Bitsch R G, Pritsch M, Clauss M, Mau H, Breusch S J. Mueller reinforcement rings in acetabular revision: Outcome in 164 hips followed for 2–17 years. Acta Orthop 2006; 77 (2): 234–41.

- Schreurs B W, Keurentjes J C, Gardeniers J W, Verdonschot N, Slooff T J, Veth R P. Acetabular revision with impacted morsellised cancellous bone grafting and a cemented acetabular component: A 20- to 25-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009; 91 (9): 1148–53.

- Schwarzer G, Schumacher M, Maurer T B, Ochsner P E. Statistical analysis of failure times in total joint replacement. J Clin Epidemiol 2001; 54 (10): 997–1003.

- Sirka A, Clauss M, Tarasevicius S, Wingstrand H, Stucinskas J, Robertsson O, Ochsner P E, Ilchmann T. Excellent long-term results of the Muller acetabular reinforcement ring in primary total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2016; 87 (2): 100–5.

- Slooff T J, Huiskes R, van Horn J, Lemmens A J. Bone grafting in total hip replacement for acetabular protrusion. Acta Orthop Scand 1984; 55 (6): 593–6.

- Taylor E D, Browne J A. Reconstruction options for acetabular revision. World J Orthop 2012; 3 (7): 95–100.

- Van Kleunen J P, Lee G C, Lementowski P W, Nelson C L, Garino J P. Acetabular revisions using trabecular metal cups and augments. J Arthroplasty 2009; 24 (6 Suppl): 64–8.

- von Roth P, Abdel M P, Harmsen W S, Berry D J. Uncemented jumbo cups for revision total hip arthroplasty: A concise follow-up, at a mean of twenty years, of a previous report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015; 97 (4): 284–7.

- Wachtl S W, Jung M, Jakob R P, Gautier E. The Burch-Schneider antiprotrusio cage in acetabular revision surgery: A mean follow-up of 12 years. J Arthroplasty 2000; 15 (8): 959–63.

- Wedemeyer C, Neuerburg C, Heep H, von Knoch F, von Knoch M, Loer F, Saxler G. Jumbo cups for revision of acetabular defects after total hip arthroplasty: A retrospective review of a case series. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2008; 128 (6): 545–50.

- Zicat B, Engh C A, Gokcen E. Patterns of osteolysis around total hip components inserted with and without cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995; 77 (3): 432–9.

- Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner P E. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med 2004; 351 (16): 1645–54.