Abstract

Background and purpose — We have previously shown that specific exercises reduced the need for surgery in subacromial pain patients at 1-year follow-up. We have now investigated whether this result was maintained after 5 years and compared the outcomes of surgery and non-surgical treatment.

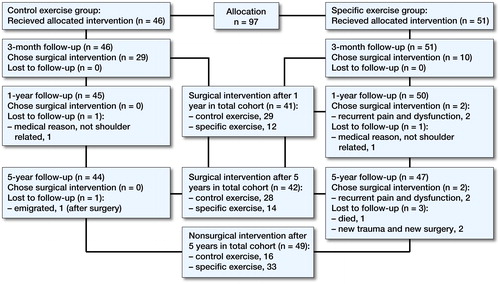

Patients and methods — 97 patients were included in the previously reported randomized study of patients on a waiting list for surgery. These patients were randomized to specific or unspecific exercises. After 3 months of exercises the patients were asked if they still wanted surgery and this was also assessed at the present 5-year follow-up. The 1-year assessment included Constant–Murley score, DASH, VAS at night, rest and activity, EQ-5D, and EQ-VAS. All these outcome assessments were repeated after 5 years in 91 of the patients.

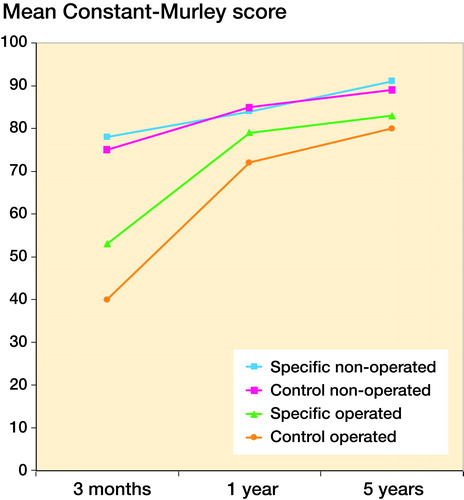

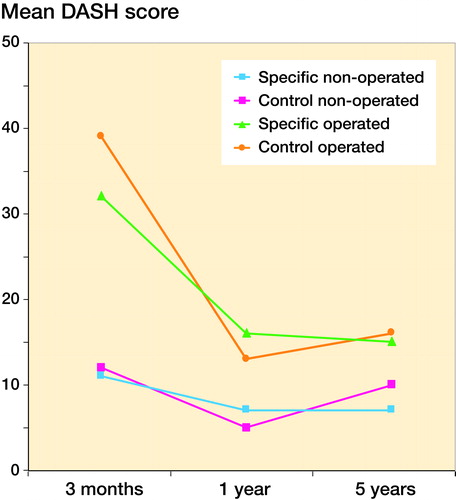

Results — At the 5-year follow-up more patients in the specific exercise group had declined surgery, 33 of 47 as compared with 16 of 44 (p = 0.001) in the unspecific exercise group. The mean Constant–Murley score continued to improve between the 1- and 5-year follow-ups in both surgically and non-surgically treated groups. On a group level there was no clinically relevant change between 1 and 5 years in any of the other outcome measures regardless of treatment.

Interpretation — This 5-year follow-up of a previously published randomized controlled trial found that specific exercises reduced the need for surgery in patients with subacromial pain. Patients not responding to specific exercises may achieve similar good results with surgery. These findings emphasize that a specific exercise program may serve as a selection tool for surgery.

In 2 previous publications we have demonstrated that a specific exercise program was more effective than an unspecific control exercise program in reducing the need for surgery in subacromial pain patients at 3- and 12-month follow-ups (Holmgren et al. Citation2012b, Hallgren et al. Citation2014). The patients treated with specific exercises responded with reduced pain and improved shoulder function despite long-standing symptoms and previous physiotherapy in primary care. Patients were continuously offered arthroscopic subacromial decompression (ASD) until the final follow-up. After 1 year 41 of 95 chose ASD because of persistent symptoms, 12 of 50 in the specific exercise group and 29 of 45 in the unspecific exercise group. These results are in line with other studies concluding that specific exercises should be the first-line treatment for patients with subacromial pain (Brox et al. Citation1999, Haahr and Andersen Citation2006, Coghlan et al. Citation2008, Ketola et al. Citation2013).

The present study is a 5-year follow-up of the original cohort. We investigated whether the previous results were maintained and compared the outcomes of surgery and non-surgical treatment. We also included a structural assessment of the rotator cuff.

Patients and methods

Participants, previous interventions, and outcome measures

In the original, single-assessor blinded, controlled trial, 97 patients recruited from the waiting list for ASD were randomized to either a specific exercise program or to an unspecific exercise program (control) (Holmgren et al. Citation2012b, Hallgren et al. Citation2014). All patients had long-standing subacromial pain and no clinical signs of major rotator cuff dysfunction defined as weakness in external and internal rotation and pathologic infraspinatus and subscapularis tests. All had undergone previous exercise therapy in primary care with an unsatisfactory result. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in (see Supplementary data). The specific exercise program focused on eccentric exercises for the rotator cuff and both eccentric and concentric exercises for the scapula-stabilizing musculature. The control exercise program included unloaded range of motion exercises for neck and shoulder without progression. The programs are described in detail in previous publications (Holmgren et al. Citation2012b, Hallgren et al. Citation2014). At the 3-month follow-up a shoulder surgeon blinded to the type of exercises asked the patients if they wanted to go through with surgery and in that case an ASD was performed as soon as possible. Surgery was performed by 1 of 2 experienced shoulder surgeons not involved in the study and included arthroscopic inspection of the glenohumeral joint and subacromial space, bursal and acromion resection. A supervised exercise program commonly used after ASD was performed postoperatively (Holmgren et al. Citation2012a). The patient’s choice of surgery or not resulted in 4 groups of patients after the 3-month assessment: specific non-operated, specific operated, control non-operated and control operated (, ). A second follow-up was performed 1 year after inclusion. At all follow-ups (3 months, 1 and 5 years) the same shoulder surgeon, blinded to group assignment, recorded the Constant–Murley (C–M) score, Disability of the Arm Shoulder and Hand questionnaire (DASH) Score (Swedish version), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) (0–100 mm) assessing pain intensity at rest, at night and at arm activity during the last 24 hours, EQ-5D, and EQ-VAS.

Table 2. Patients participating in the 5-year follow-up

5-year follow-up

All 95 patients who participated in the 1-year follow-up were invited to a 5-year follow-up performed by a shoulder surgeon blinded to the initial group randomization. The data collection was identical to the 1-year follow-up including the patient’s choice of surgery or not and the clinical outcome measurements described above (Hallgren et al. Citation2014). The patients also filled in a questionnaire asking for use of health care, present shoulder symptoms, recurrence, and shoulder exercise habits during the past 4 years. Ultrasound examinations of the rotator cuff were performed by an experienced assessor, blinded to the findings at inclusion. A Siemens Acuson Sequoia 512 (Acuson, Mountain View, CA, USA) with a variable 8–10 MHz linear array transducer was used at all examinations. The status of the rotator cuff was divided into: intact, partial-thickness tear (PTT), or full-thickness tear (FTT) referring to the depth of the tendon (Bjornsson et al. Citation2011). Tear size in mm was not measured. Tear progression was defined as progression from intact tendons at baseline to a partial- or full-thickness tear or from an initial partial- to a full-thickness tear at the 5-year follow-up. A full-thickness tear at inclusion that had enlarged to affect an adjacent, previously intact, tendon was also considered a progression.

Statistics

Pearson’s chi-square test was used to compare the proportion of patients choosing surgery in the originally randomized group, and also for the proportions of patients with progression of a cuff tear. Since some patients during this period needed surgery in addition to exercises, group comparison at the 5-year follow-up was performed using a paired t-test. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Ethics, registration, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

Ethical approval was obtained for the 5-year follow-up from the regional committee for medical ethics in Linköping 2016-10-27 (dnr:2016/444-32). Written consent to participate in the study was collected from all patients after verbal and written information. The original trial was registered at Clinical trials: NCT01037673. The study was funded by the Linköping University Hospital and Linköping University but no other support, financial or other, was received for this study. No competing interests declared.

Results

5-year follow-up

At the 5-year follow-up 91 of the 95 invited patients could be reassessed (). Any patient operated or re-operated had had this procedure performed at least 1 year prior to the 5-year follow-up. The proportion of patients not wanting surgery, who were satisfied with the exercise treatment, was still after 5 years larger (p = 0.001) among those originally randomized to the specific exercise group (33/47) compared with the control group (16/44). Between the 1-year and 5-year follow-ups 2 patients had chosen ASD, both initially randomized to the specific exercise group (). All patients in the 4 different groups continued to improve in mean C–M score between the 1- and 5-year follow-ups (, see Supplementary data, ). There were no clinically relevant changes in the mean DASH scores between the 1- and 5-year follow-ups (, see Supplementary data, ).

Figure 2. Mean Constant-Murley score values at the previous 3-month and 1-year follow-up and in addition the 5-year follow-up in the 4 groups of patients; specific non-operated, control non-operated, specific operated and control operated. These groups were created after the choice of surgery or not at the 3-month assessment.

Figure 3. Mean Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand score values at 3-month, 1-year and 5-year follow-up in the 4 groups of patients; specific non-operated, control non-operated, specific operated and control operated. These groups were created after the choice of surgery or not at the 3-month assessment.

Table 5. Rotator cuff status, assessed with ultrasound. Findings from baseline in the original RCT and from the 5-year follow-up divided into those treated with surgery and those without surgery up until the 5-year follow-up

When dividing the cohort into non-operated and operated patients from both exercise groups, the non-operated group had reached a significantly higher mean C–M score of 90 points (95% CI 82–90) compared with the operated group at 81 points (95% CI 77–85) (p = 0.002) at the 5-year follow up (). At the 5-year follow-up non-operated patients scored better in pain at rest (p = 0.05) and at night (p = 0.02).

Table 4. Mean Constant-Murley score (C-M) and standard deviation (SD) in operated (n = 42) and non-operated (n = 48) patients at 3-month, 1-year and 5-year follow-ups for the 90 patients with 5-year C–M score

From baseline to 5-year follow-up the change in mean C–M score was 38 points in the non-operated group and 42 points in the operated group. A similar improvement was seen in the mean DASH score in operated (24 points) and non-operated patients (19 points) (, see Supplementary data, ). No clinically relevant changes were seen in the VAS, EQ-5D, and EQ-VAS recordings during the same time period (, see Supplementary data).

The 5-year follow-up questionnaire revealed that 7 of 49 individuals in the non-operated group had had further treatment after the 1-year follow-up, 5 a subacromial corticosteroid injection and 2 had further physiotherapy instructions. In the operated group 4 of 42 patients had received further treatment, 3 were re-operated and 1 had had osteopathy treatment. All 3 reoperations included acromioplasty, biceps tenotomy, and lateral clavicle resection. These re-operated patients had a similar 5-year outcome in all of the outcome measures as compared with the rest of the cohort. 44 of the patients in the non-operated group reported that they had no or slight shoulder dysfunction compared with 31 in the operated group 5 years after inclusion. None of the patients in the non-operated group was worse compared with the 1-year assessment but 4 patients rated that they had the same symptoms ongoing. In the operated group 1 person rated that he was worse and 3 persons that they still had the same symptoms as at the 1-year follow-up. In the non-operated group 28 patients had continued to perform exercises involving the shoulder compared with 17 in the operated group.

The ultrasound examination at 5 years showed that there were 38 rotator-cuff tears, including both partial- and full-thickness tears, in the cohort as compared with 26 tears at baseline. Significantly more patients (n = 16) in the operated group had progression of the tendon affection or a new tendon lesion as compared with (n = 9) the non-operated group (p = 0.002) ().

Discussion

Our main findings are that after 5 years more patients in the specific exercise group could still avoid surgery as compared with the unspecific exercise group and that patients who had not benefited from exercise treatment had a good outcome after surgery. Supervised exercise as the first line of treatment for subacromial pain is supported by results from other randomized trials and this study adds further evidence to the current recommendations (Brox et al. Citation1999, Haahr and Andersen Citation2006, Ketola et al. Citation2013, Haik et al. Citation2016). Our exercise program included both eccentric and concentric exercises for the rotator cuff and the scapula-stabilizing muscles. Pain was allowed to a certain limit and progression of load was guided by a pain-monitoring model (Thomee Citation1997). The rationale was that an increased range of motion, strength, and endurance would help to normalize the scapulohumeral kinematics and centralize the humeral head in the glenoid fossa during movement (Kromer et al. Citation2013, Maenhout et al. Citation2013, Struyf et al. Citation2013). Exercises are also hypothesized to have an inhibitory effect on central sensitization that may occur in many of the unilateral subacromial pain patients’ symptoms (Sanchis et al. Citation2015). Since subacromial pain has a multifactorial origin it is impossible to know which one of the components, or a combination of them, could explain the positive outcome after our specific exercise strategy (Lewis Citation2016). Reasons for the remaining effect in the current study, 5 years after a 3-month specific exercise intervention, are unclear. Patients may have learned to correct their shoulder kinematics to use their shoulder more functionally over the years (Curry et al. Citation2015). Also, a likely positive effect of the program was the “vocal treatment”, including information on their shoulder disorder, ergonomics, and posture correction (Adolfsson Citation2015, Lewis Citation2016). The mean age in the cohort was 58 (38–69) (see ). The mean C–M score of the cohort was 86 which corresponds well with age and sex-adjusted C–M scores in the healthy population (Katolik et al. Citation2005). This reflects that the patients in the present study, on a group-level, reached a very good outcome.

Brox et al. (Citation1999) compared surgery, supervised exercises, and placebo, and found that 25% of the patients in the placebo group reported a satisfactory result and contributed this to the natural course of the disease. In our study 16 of the 44 patients in the control exercise group chose not to be operated despite previous long-standing symptoms and an unsatisfactory result of physiotherapy in primary care. The positive result in this third of the group might be explained by multiple factors, the natural course being one (Arroll and Goodyear-Smith Citation2005, Crawshaw et al. Citation2010).

When considering the other objective of this study, to compare surgical and non-surgical treatment, we found that the change over time in mean C–M score was well above the level for clinical relevance, reported to be between 17 and 24 points, in both operated and non-operated groups (Holmgren et al. Citation2014). These results are also in line with the clinically relevant pain reduction displayed in the VAS recordings and the overall patient satisfaction in both groups (Tashjian et al. Citation2009). The operated group showed a similar clinical improvement but this occurred after the surgical intervention.

The presence and progression of cuff tears was more often found in the operated group, a result that is in line with our previous study, where we found that patients with full-thickness tears and the lowest baseline scores were more prone to choose surgery (Hallgren et al. Citation2014). A structural cuff pathology may in part explain the inferior result in the operated group as rotator cuff disease may be the leading cause of prolonged shoulder pain and disability (Adler et al. Citation2008). Also the non-operated group included patients with progression of structural lesions that may be the result of natural aging, despite which they had an excellent 5-year result measured with several different outcomes. Multiple factors not related to pathoanatomy, such as mental health, age, genetics, comorbidities, and female sex, are found to influence outcome after treatment of subacromial pain with or without cuff tears (Curry et al. Citation2015, Lewis Citation2016). The multifactorial cause of symptoms may explain why a specific exercise strategy addressing several mechanisms is successful for the majority of patients.

As a result of the growing body of evidence supporting structured exercises as treatment of subacromial pain, ASD has become questioned (Brox et al. Citation1999, Haahr and Andersen Citation2006, Ketola et al. Citation2013, Haik et al. Citation2016). Ketola et al. (Citation2013, Citation2015) concluded that patients without satisfactory symptom relief after non-operative treatment did not do any better after surgery. These conclusions are in conflict with our findings that patients treated with ASD improved substantially and with the same magnitude as the non-operated. Comparison between previous controlled studies is, however, difficult because of difference in inclusion criteria and baseline scores. The cohort in the study by Ketola et al. (Citation2013) may have included patients with other disorders not responsive to any of the treatments used. We used strict inclusion criteria and we believe that our study group was homogeneous in terms of symptoms and all patients rated low baseline values on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HAD), a screening tool for depression and anxiety (Zigmond and Snaith Citation1983, Holmgren et al. Citation2012b). Understanding of the individual pathomechanisms is difficult but the results from other and our studies appear to confirm that a specific exercise strategy should be the initial treatment for subacromial pain with or without small rotator cuff tears (Holmgren et al. Citation2012b, Ketola et al. Citation2013, Hallgren et al. Citation2014). Acromioplasty can be recommended for patients without clinical signs of major cuff dysfunction and with unsatisfactory relief from specific exercise treatment.

A limitation of our study is the lack of an observational group to follow the natural course, but since all patients had been recommended some kind of exercises in primary care before inclusion in the original randomized trial we could not study the natural course. Since the investigation is based on a sample of patients with similar symptoms and radiological findings, performed at 1 hospital in a trial setting, the generalizability to all subacromial pain patients may be limited. Further, ultrasound is reportedly more accurate in detecting full-thickness tears than partial thickness tears (Cole et al. Citation2016). To handle this potential insecurity, we used experienced ultrasound assessors and the same equipment at all assessments. Strengths are the 5-year longitudinal data, both clinically and structural, on 91 of the 97 patients in the original cohort, making this study unique.

In summary, this 5-year follow-up supports the hypothesis that a specific exercise strategy should be the initial treatment of patients with subacromial pain. Patients not responding to specific exercises and those with more pronounced pathology may need surgery to reach a similar good result and the specific exercise program may serve as a selection tool for surgery.

Supplementary data

Tables 1 and 3 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1364069

HB, TH, BÖ, KJ and LA conceived and designed the study protocol. TH and KJ designed the physiotherapy interventions. TH did the statistical analyses with assistance from a statistician (HM). HB and AP were the blinded assessor. HB drafted the manuscript, and TH, BÖ, KJ and LA contributed to the manuscript.

We thank Henrik Magnusson, statistician at the Linköping University for help with the statistical analyses.

Acta thanks Klaus Bak and Ron Diercks for help with peer review of this study.

IORT_A_1364069_SUPP.PDF

Download PDF (31.6 KB)- Adler R S, Fealy S, Rudzki J R, Kadrmas W, Verma NN, Pearle A, Lyman S, Warren R F. Rotator cuff in asymptomatic volunteers: Contrast-enhanced US depiction of intratendinous and peritendinous vascularity. Radiology 2008; 248 (3): 954–61.

- Adolfsson L. Is surgery for the subacromial pain syndrome ever indicated? Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (6): 639–40.

- Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F. Corticosteroid injections for painful shoulder: A meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract 2005; 55 (512): 224–8.

- Bjornsson H C, Norlin R, Johansson K, Adolfsson L E. The influence of age, delay of repair, and tendon involvement in acute rotator cuff tears: Structural and clinical outcomes after repair of 42 shoulders. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (2): 187–92.

- Brox J I, Gjengedal E, Uppheim G, Bohmer A S, Brevik J I, Ljunggren A E, Staff P H. Arthroscopic surgery versus supervised exercises in patients with rotator cuff disease (stage II impingement syndrome): A prospective, randomized, controlled study in 125 patients with a 2 1/2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1999; 8 (2): 102–11.

- Coghlan J A, Buchbinder R, Green S, Johnston R V, Bell S N. Surgery for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008 (1): 3.

- Cole B, Twibill K, Lam P, Hackett L, Murrell G A. Not all ultrasounds are created equal: General sonography versus musculoskeletal sonography in the detection of rotator cuff tears. Shoulder Elbow 2016; 8 (4): 250–7.

- Crawshaw D P, Helliwell P S, Hensor E M, Hay E M, Aldous S J, Conaghan P G. Exercise therapy after corticosteroid injection for moderate to severe shoulder pain: Large pragmatic randomised trial. BMJ 2010; 340: c3037.

- Curry E J, Matzkin E E, Dong Y, Higgins L D, Katz J N, Jain N B. Structural characteristics are not associated with pain and function in rotator cuff tears: The ROW Cohort Study. Orthop J Sports Med 2015; 3 (5): 2325967115584596. [Epub]

- Haahr J P, Andersen J H. Exercises may be as efficient as subacromial decompression in patients with subacromial stage II impingement: 4–8-years’ follow-up in a prospective, randomized study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2006; 35 (3): 224–8.

- Haik M N, Alburquerque-Sendin F, Moreira R F, Pires E D, Camargo P R. Effectiveness of physical therapy treatment of clearly defined subacromial pain: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med 2016; 50(18): 1124–34.

- Hallgren H C, Holmgren T, Oberg B, Johansson K, Adolfsson L E. A specific exercise strategy reduced the need for surgery in subacromial pain patients. Br J Sports Med 2014; 48 (19): 1431–6.

- Holmgren T, Oberg B, Sjoberg I, Johansson K. Supervised strengthening exercises versus home-based movement exercises after arthroscopic acromioplasty: A randomized clinical trial. J Rehabil Med 2012a; 44(1): 12–8.

- Holmgren T, Bjornsson Hallgren H, Oberg B, Adolfsson L, Johansson K. Effect of specific exercise strategy on need for surgery in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: Randomised controlled study. BMJ 2012b; 344: e787.

- Holmgren T, Oberg B, Adolfsson L, Bjornsson Hallgren H, Johansson K. Minimal important changes in the Constant–Murley score in patients with subacromial pain. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014; 23 (8): 1083–90.

- Katolik L I, Romeo A A, Cole B J, Verma N N, Hayden J K, Bach B R. Normalization of the Constant score. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005; 14 (3): 279–85.

- Ketola S, Lehtinen J, Rousi T, Nissinen M, Huhtala H, Konttinen Y T, Arnala I. No evidence of long-term benefits of arthroscopic acromioplasty in the treatment of shoulder impingement syndrome: Five-year results of a randomised controlled trial. Bone Joint Res 2013; 2 (7): 132–9.

- Ketola S, Lehtinen J, Rousi T, Nissinen M, Huhtala H, Arnala I. Which patients do not recover from shoulder impingement syndrome, either with operative treatment or with nonoperative treatment? Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (6): 641–6.

- Kromer T O, de Bie R A, Bastiaenen C H. Physiotherapy in patients with clinical signs of shoulder impingement syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med 2013; 45 (5): 488–97.

- Lewis J. Rotator cuff related shoulder pain: Assessment, management and uncertainties. Man Ther 2016; 23: 57–68.

- Maenhout A G, Mahieu N N, De Muynck M, De Wilde L F, Cools A M. Does adding heavy load eccentric training to rehabilitation of patients with unilateral subacromial impingement result in better outcome? A randomized, clinical trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013; 21 (5): 1158–67.

- Sanchis M N, Lluch E, Nijs J, Struyf F, Kangasperko M. The role of central sensitization in shoulder pain: A systematic literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2015; 44 (6): 710–16.

- Struyf F, Nijs J, Mollekens S, Jeurissen I, Truijen S, Mottram S, Meeusen R. Scapular-focused treatment in patients with shoulder impingement syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. Clin Rheumatol. 2013; 32 (1): 73–85.

- Tashjian R Z, Farnham J M, Albright F S, Teerlink C C, Cannon-Albright L A. Evidence for an inherited predisposition contributing to the risk for rotator cuff disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009; 91 (5): 1136–42.

- Thomee R. A comprehensive treatment approach for patellofemoral pain syndrome in young women. Phys Ther 1997; 77 (12): 1690–703.

- Zigmond A S, Snaith R P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67 (6): 361–70.