Abstract

Background and purpose — Hip displacement is frequent in nonambulatory children with cerebral palsy (CP) and treatment is controversial. This prospective study assesses the effectiveness of soft-tissue releases to treat hip subluxation, analyses prognostic factors for outcome, and identifies time to failure in hips with poor outcome.

Patients and methods — 37 children (16 girls) with hip subluxation were recruited from the population-based screening program for children with CP in Norway. They had consecutively undergone soft-tissue releases (bilateral tenotomies of adductors and iliopsoas) at a mean age of 5.0 (2.8–7.2) years. Functional classification was Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) level III in 9 children, level IV in 10, and level V in 18 children. The outcome was termed good if the patient had not undergone further hip surgery and if the migration percentage (MP) of the worst hip at the latest follow-up was <50%. The mean follow-up time was 7.3 (5.1–9.8) years.

Results — The outcome was good in all the ambulatory children and in 17 of 28 of the nonambulatory children. The only independent preoperative risk factor for poor outcome was MP ≥50%. The mean time to failure was 2.2 (1–5) years postoperatively and the reasons for failure were insufficient initial correction and later deterioration of displacement.

Interpretation — Bilateral soft-tissue release is recommended in both ambulatory and nonambulatory children with hip subluxation. The operation should be performed before the hip displacement reaches 50%.

Hip displacement occurs frequently in children with cerebral palsy (CP), especially in nonambulant children. Population-based studies have shown a markedly increasing rate of hip displacement according to reduced functional level of the child, from 0–5% at Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS; Palisano et al. Citation1997) level I to 70–90% at level V (Soo et al. Citation2006, Hägglund et al. Citation2007, Connelly et al. Citation2009, Terjesen Citation2012). If complete dislocation occurs, hip pain and severe problems with ambulation, sitting balance, and perineal nursing care may arise (Samilson et al. Citation1972, Letts et al. Citation1984). Therefore, screening programs aimed at early diagnosis and treatment of hip displacement have been developed (Soo et al. Citation2006, Hägglund et al. Citation2005).

Soft-tissue procedures like adductor and psoas releases have been recommended as prophylaxis against deterioration of hip displacement. Although such procedures had a good effect in 70–80% of the hips in studies with a mean follow-up of 3–4 years (Sharrard et al. Citation1975, Kalen and Bleck Citation1985, Miller et al. Citation1997), the rate of poor outcome and relapse have been more than 50% in other studies with a longer follow-up period (Turker and Lee Citation2000, Shore et al. Citation2012). It has not been clarified when and why the failures of surgery occur. Whether failures are caused by poor primary correction of displacement or by later deterioration after satisfactory primary correction is therefore unclear and needs further analysis.

A population-based registration of children with CP was initiated in southeast Norway in 2006. Based on this registry, the natural history of hip development in 335 children has previously been published (Terjesen Citation2012). Children with migration percentage (MP) above 33% have been recommended operative treatment. According to our guidelines soft-tissue releases should be used in cases of mild and moderate subluxation, whereas osseous procedures should be added in children with severe subluxation (MP ≥50%). The aims of the present prospective study were to assess the outcome of soft-tissue releases in this registry population, to identify factors that were associated with good or poor prognosis, and to clarify time to failure in children with poor outcome.

Patients and methods

In 2006 the CP follow-up program(CPOP) for Norway was started, representing about 50% of the population in the country. All children with CP born after 1 January 2002 and living in 1 of the 10 southeastern counties were included after informed consent from their parents. The diagnosis and type of CP were determined according to Hagberg et al. (Citation2001) by neuropaediatricians working at the child habilitation centers (1 in each county). The CPOP program includes systematic clinical and radiographic follow-up.

At the end of 2011, the CPOP register contained radiographs of the hips of 335 children born during the 5-year period 2002 to 2006. 60 children had undergone operative treatment for hip displacement. 1 patient was excluded because he had been operated at another hospital and the guidelines for surgery had not been followed. Pelvic and/or femoral osteotomies had been performed in 22 children. The present study comprised the remaining 37 children (21 boys) who had undergone soft-tissue releases. Mean age at surgery was 5.0 (2.8–7.2) years. 33 children had bilateral spastic CP (quadriplegia in 19 children and diplegia in 14) and 4 children had dyskinesia (variable muscle tone).

The functional level of the children was determined by physiotherapists at the habilitation centers, who examined the children twice a year up to the age of 6 years and then once a year. Function was assessed using the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GFMCS) (Palisano et al. Citation1997), with decreasing functional level as the GMFCS class increases. Children at GMFCS level III have independent walking ability but need support (canes, crutches, walker), whereas children at GMFCS levels IV and V are nonambulatory. The distribution was level III in 9 children, level IV in 10, and level V in 18 children. 5 children had had intrathecal baclofen therapy.

Radiographic assessment

Radiographic examination was carried out at the university hospital or at the local county hospital. An anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis and hip joints was obtained with the child in the supine position. Care was taken to position the child correctly with the legs parallel and to avoid rotation of the pelvis and legs. The radiographs from the local hospitals were sent electronically to the university hospital and stored in our PACS. The radiographic measurements were performed by the author, who has many years of experience in evaluating radiographs of children’s hips. The radiographs were 2-fold enlarged in order to obtain better visualization of the landmarks and the measurements were performed digitally with the standard equipment in PACS.

The following radiographic parameters were measured: migration percentage (Reimers Citation1980), acetabular index (Hilgenreiner Citation1925), and pelvic obliquity. Migration percentage (MP) is the percentage of the femoral head lateral to the acetabulum (lateral to Perkins’ line), measured parallel to Hilgenreiner’s line. The hips were classified as normal (MP <33%), subluxation (MP 33–89%), and dislocation (MP ≥90%) (Reimers Citation1980). Acetabular index (AI) is the slope of the acetabular roof, which is the angle between the line through the medial and lateral edges of the acetabular roof and Hilgenreiner’s line. Pelvic obliquity (PO) was measured as the angle between the horizontal line and the line between the lowest points of the pelvic bones on the right and left side. Angles <3° were not registered as PO.

According to the study protocol a pelvic radiograph should be taken once a year both pre- and postoperatively. Based on the worst hip (the hip with the highest MP) at the initial and later radiographs, the progression in MP per year pre- and postoperatively could be followed. The results at follow-up were graded into 2 categories according to Shore et al. (Citation2012), using the worst hip of each patient (the hip with the highest MP). The outcome was termed satisfactory (“success”) when MP at the last follow-up was <50%. If final MP was ≥50% and/or the patient had undergone subsequent bony surgery (pelvic and/or femoral osteotomies) to improve femoral head coverage, the outcome was unsatisfactory (“failure”).

Reduction in MP caused by the operation (“primary correction”) was defined as difference between preoperative MP and MP 1 year postoperatively. The primary correction was termed satisfactory if MP had been reduced by ≥10% and MP was <50% at the 1-year follow-up.

Operative procedures

The standard procedure was bilateral proximal tenotomies of adductor longus and gracilis through a short oblique incision over the origin of adductor longus. Through the same incision tenotomy of the iliopsoas tendon just proximal to its insertion on the lesser trochanter was performed in all but 2 children. If hip abduction was still limited, a partial myotomy of the adductor brevis was also done (16 children) until 45–50° abduction was achieved. Extended adductor release including adductor brevis was performed more frequently in children at GMFCS level V (11 of 18 children) than at level IV (4 of 10) and III (1 of 9 children). Distal tenotomy of the medial hamstrings was done in 9 children and elongation of the Achilles tendon or gastrocnemius muscle was done in 14 children. Postoperatively, an abduction plaster cast from the proximal thighs to the ankles or toes with about 30° abduction of both hips and 10–20° of knee flexion was worn for 5–6 weeks. Thereafter, physiotherapy was continued to maintain range of motion and strength of the lower extremities.

There were no postoperative wound infections. When the plaster cast was removed, it was observed that 8 children had heel sores because of pressure from the plaster cast. The sores healed uneventfully without further problems.

Statistics

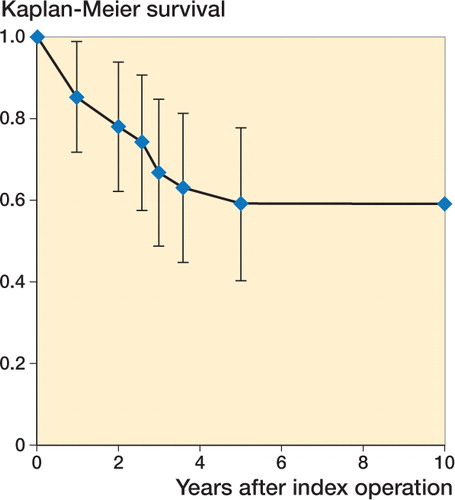

The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical data were analyzed with Pearson’s chi-square test. Continuous data were analyzed using Student’s t-test for independent samples. Risk factors for poor outcome (failure) were estimated as relative risks using Poisson loglinear regression. All tests were 2-sided. Differences were considered significant when the p-value was <0.05. The percentage survival according to postoperative time (years) was described with a Kaplan–Meier plot.

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

The study was approved by the Regional Committee of Medical Research Ethics (no. 2012/2258) and the hospital’s Privacy and Data Protection Officer. No external funding was received for this study and there are no conflicts of interest.

Results

The mean preoperative MP of the worst hip was 47% (31–88%) and of the best side 30% (0–50%). 25 children had mild or moderate subluxation (MP <50%) and 12 children (10 at GMFCS level V and 2 at level IV) had severe subluxation (MP ≥50%), of which 4 had MP >60% (66–88%). Subluxation was unilateral in 20 children and bilateral in 17; thus, altogether 54 hips were subluxated preoperatively (12 hips at GMFCS level III and 42 hips at level IV/V).

1 child died 3.5 years after the operation. The mean postoperative follow-up time of the children who have not undergone subsequent hip surgery was 7.3 (5.1–9.8) years and the mean patient age at last follow-up was 12.3 (9.5–15) years. The radiographic outcome was satisfactory (“success”) in 26 children and unsatisfactory (“failure”) in 11 children. The outcome was good in all the ambulatory children and in 17 of 28 of the nonambulatory children. Since all the failures were unilateral, 31 of the 42 preoperatively subluxated hips in nonambulatory children had good results. There was a statistically significant association (chi-square test) between outcome and gait function, since children at GMFCS level III had better outcome than the combined levels IV/V (p = 0.03), but the difference between levels IV and V was not statistically significant (p = 0.4).

Potential risk factors for failure are shown in . There was a statistically significant association between failure and preoperative MP ≥50% (relative risk 3.6; 95% confidence interval 1.1–13). This also represents a clinically important risk factor. There were no statistically significant associations between outcome and sex, GMFCS levels, uni- vs. bilateral subluxation, CP types, age at surgery, preoperative AI, and preoperative PO.

Table 1. Potential preoperative risk factors for failure of soft-tissue releases in 37 children, estimated as relative risks (RR) for failure, using Poisson loglinear regression

The development in MP according to time and final outcome is shown in . Preoperative MP and MP 1 year postoperatively were statistically significantly larger in children with failure compared with those who had a satisfactory outcome. Soft-tissue releases caused a mean “primary correction” in MP of 12% and there were no statistically significant differences between the GMFCS groups. In children with success the mean reduction was 14% (–3% to 39%), which was statistically significantly larger than the MP reduction of 6% (0–18%) in children with failure. The primary correction was satisfactory in 21 children and unsatisfactory in 16 children. Final outcome was good in all the children except 1 with satisfactory primary correction () and in 6 of the 16 children with unsatisfactory primary correction. All except 1 of the 11 patients with poor final outcome had unsatisfactory primary correction (see ).

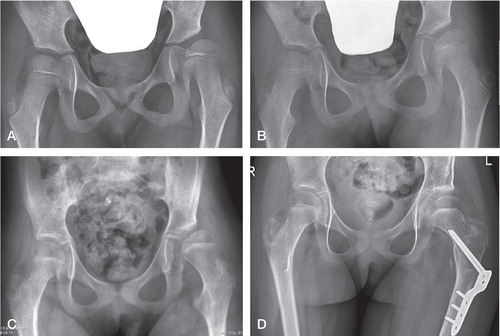

Figure 1. A. Preoperative radiograph of a 5 year 5-months-old boy with spastic quadriplegia (GMFCS level V), showing bilateral hip subluxation with migration percentage (MP) 40% (right hip) and 48% (left hip). B. 1.8 years after soft-tissue releases, showing good primary correction; MP of the left hip was reduced from 48% to 32%. C. 6.7 years postoperatively, showing good outcome with MP 15% (right hip) and 25% (left hip).

Figure 2. A.Preoperative radiograph of a 5 year 5 months old girl with spastic quadriplegia (GMFCS level V), showing subluxation of her left hip with migration percentage (MP) 50%. B. 1 year after soft-tissue releases, showing unsatisfactory primary correction; MP was reduced from 50% to 43%. C. 4.4 years postoperatively, showing poor outcome with MP 54% of the left hip. D. 3.1 years after Dega-type pelvic osteotomy and varus femoral osteotomy of the left hip (MP 31%).

Table 2. Migration percentage (MP) pre- and postoperatively (mean MP of the worst hip in each patient) in 37 children and comparison between children with good and poor final radiographic results

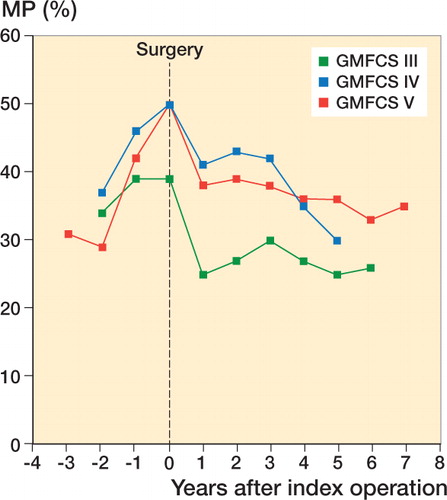

Since the children were followed with pelvic radiographs both pre- and postoperatively, the progression in MP (change per year) could be calculated (). The mean preoperative progression was larger in children with poor outcome (11% per year) than in those with good outcome (5% per year), but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.08). During the postoperative period, however, from 1 year postoperatively to the last follow-up, progression in MP per year was markedly larger in children with failure. In children with satisfactory final outcome there was a slight mean reduction in MP (0.6% per year) and only 3 children out of 26 had yearly MP increase >1.0% (1.3–2.5%). shows pre- and postoperative development of MP according to GMFCS levels.

Figure 3. Development of migration percentage (MP) according to functional levels (GMFCS) pre- and postoperatively.

A Kaplan–Meier survival plot of the nonambulatory children, with time from index surgery to failure as “survival”, is shown in . The mean time to failure (MP ≥50% or additional surgery) was 2.2 (1–5) years and all except 1 patient had survival of 3 years or less. 10 of the 11 children with failures have undergone additional surgery at a mean follow-up period of 3.2 (0.9–7.2) years. Mean MP before reoperation was 59% (46–84%). Dega-type pelvic osteotomy and femoral varus osteotomy was performed in 7 children and 3 children underwent femoral osteotomy only.

Discussion

This study showed good results after soft-tissue releases in more than two-thirds of the children. Previous studies have shown a wide range of good results, from 32% (Shore et al. Citation2012) to 90% (Onimus et al. Citation1991). This large difference could be due several factors, including functional level, follow-up time, and definitions of success and failure. Recent studies have reported that the results deteriorate with increasing follow-up period (Turker and Lee Citation2000, Presedo et al. Citation2005, Shore et al. Citation2012). Moreover, worse results will be obtained if only the worst hip for each patient is reported compared with reporting each hip separately. This is obvious from the present results, with a success rate of 17/28 in nonambulatory children and 31/42 when all the preoperatively subluxated hips were included. Reporting only the worst hip is more clinically relevant (Turker and Lee Citation2000, Terjesen et al. Citation2005), since it is of little help to the patient that 1 hip improves if the other hip deteriorates to severe subluxation or dislocation. Therefore, only studies with a mean follow-up of 7 years or more and reporting the results of the worst hip in each patient are relevant for comparison with the present results.

We used the classification system described by Shore et al. (Citation2012), which defined “failure” as the need for subsequent surgery to improve hip displacement or MP of the worst hip ≥50% at the last follow-up. Similar classifications were used in other studies, although the cut-off for good results was MP 40% in 1 study (Presedo et al. Citation2005) and 80% in another (Turker and Lee Citation2000). Since 80% displacement practically is complete dislocation, a 50% limit seems more adequate. This limit is also clinically relevant since a recent study of children with CP showed that MP above 50% was strongly associated with hip pain (Ramstad and Terjesen Citation2016).

All the ambulatory children had a good final outcome. This confirmed previous studies with good outcome in 66% (Shore et al. Citation2012) and 89% of ambulatory patients (Presedo et al. Citation2005). In nonambulatory children (GMFCS levels IV and V) outcome is markedly worse. Our rate of 0.6 good results in this group was in accordance with 0.6 reported by Presedo et al. (Citation2005), whereas worse outcome with good results in 0.4 was found by Turker and Lee (Citation2000) and only 0.3 by Shore et al. (Citation2012). What could the reasons be for the large discrepancy between the present results in nonambulatory children and those of Shore? One reason could be that we applied somewhat more radical surgery, since iliopsoas tenotomy was performed in almost all the patients and adductor brevis myotomy in more than half of the nonambulatory children, whereas Shore et al. (Citation2012) performed adductor brevis myotomy in only “a small number of hips” and did not do iliopsoas tenotomy in about one-fourth of the patients.

High preoperative MP as risk factor for failure is in accordance with previous studies (Turker and Lee Citation2000, Shore et al. Citation2012). Mean preoperative MP of the worst hip in the present study was 45% in patients with a satisfactory outcome and 54% in those with failure. The corresponding MP values were 33% and 43% in the study of Turker and Lee (Citation2000) and 20–21% and 45–46% by Shore et al. (Citation2012), but it is unclear whether these values refer to all the hips or only to the worst hip of each patient. The clinical consequence seems to be that soft-tissue releases should be performed before MP reaches 50%. Since the natural history in nonambulatory children is a marked progression in MP, 9% per year in children under 4 years of age and 4% per year in older children (Terjesen Citation2012), a close screening program with yearly radiographs is needed to monitor the development of hip displacement.

Shore et al. (Citation2012) analyzed outcome after soft-tissue releases according to functional levels defined by the GMFCS criteria. Using univariable analysis, they found a statistically significant increase in failures with decreasing functional levels from level II to level V. However, in multivariable analysis and adjusted for preoperative MP, the GMFCS levels III, IV, and V had a similar failure risk. In accordance with this, the present results showed no significant difference in outcome between GMFCS levels IV and V, but the outcome was better in level III.

The frequency of unsatisfactory results increases with duration of follow-up, but no previous study has systematically evaluated whether failures occur because of insufficient primary correction (within 1 year postoperatively) or because of later deterioration of hip displacement. The reason is probably that the patients in previous studies were not followed with yearly measurements of MP during the postoperative period (Turker and Lee Citation2000, Presedo et al. Citation2005, Shore et al. Citation2012). The present findings indicate that both causes of failure are of importance. All except 1 of the 11 patients with poor final outcome had unsatisfactory primary correction, and progression in MP during further follow-up was larger in this group compared with children with good outcome. The clinical consequence is that patients with unsatisfactory primary correction 1 year postoperatively should be further followed with yearly radiographs, in order to detect deterioration as early as possible and be considered for reoperation with osseous reconstruction. A high MP 1 year postoperatively as risk factor for final failure was also reported by Presedo et al. (Citation2005). They had a mean MP of 23% in patients with success and 34% in those with failure, whereas we had somewhat higher MP in both groups (30% and 48%, respectively).

Shore et al. (Citation2012) found that the mean time from soft-tissue releases to failure was 4.0 years. Our experience was somewhat different, since mean time to failure was 2.2 years and only 1 patient had failure after more than 3 years postoperatively. The closer postoperative radiographic follow-up in the present study could be the reason for the shorter time to failure. There was no trend towards deterioration of hip displacement after the first postoperative year in patients with good final outcome, indicating that the risk of later relapse is small in this group.

One obvious limitation of the present study is the small number of patients, which could reduce the reliability of the statistical evaluation. The strengths of the study are that it was prospective and population-based. Moreover, the follow-up rate was 100% and the patients were followed yearly with MP measurements both pre- and postoperatively.

Should the guidelines for surgery in our screening program be changed? Since the results of soft-tissue releases in ambulatory children and in children with mild or moderate subluxation were satisfactory, no change in treatment concepts for these groups seems necessary. Treatment is more controversial in nonambulatory children with MP ≥50%. Although failure occurred in more than half the patients with quadriplegia, Turker and Lee (Citation2000) still recommended use of adductor tenotomies for younger children, because it prevented further subluxation in some patients and often aided in perineal hygiene and seating. Shore et al. (Citation2012) considered adductor tenotomies as their index procedure for children at GMFCS levels IV and V, but they explain to the parents that the procedure functions as a temporizing measure and is associated with a low rate of success, defined as permanently stable hips. A more optimistic attitude could be justified based on the present study, where 17 of 28 children at GMFCS levels IV or V had good results. However, the outcome in children with severe subluxation (MP ≥50%) was worse (5 of 12 children had satisfactory results). Primary osseous reconstruction with pelvic and femoral osteotomies seems advisable in such cases. This is, however, a rather extensive and radical operation. One reason why the simpler soft-tissue release was performed in some children who, according to our guidelines, should have had osteotomies was deterioration of hip displacement while the child was on the rather long waiting list for surgery. Another reason was that the patient had other severe medical problems or was in reduced general condition, which made the parents or doctors prefer a less extensive procedure. Thus, our general guidelines, with soft-tissue releases when MP <50% and additional osseous surgery when MP ≥50%, hardly need to be changed, but it is allowable to deviate from this policy in individual cases.

Acta thanks Gunnar Hägglund and other anonymous reviewers for help with peer review of this study.

Supplementary data

Table 3 (a general table with the most important clinical and radiographic data on all the patients) is available in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1365471

The author would like to thank the physiotherapists of the child habilitation teams who coordinated the radiographic screening. He also thanks the statistician Are Hugo Pripp for help with the statistical analyses.

IORT_A_1365471_SUPP.PDF

Download PDF (25.9 KB)- Connelly A, Flett P, Graham H K, Oates J. Hip surveillance in Tasmanian children with cerebral palsy. J Paediatr Child Health 2009; 45: 437–43.

- Hagberg B, Hagberg G, Beckung E, Ulvebrant P. Changing panorama of cerebral palsy in Sweden, VIII: Prevalence and origin in the birth year period 1991-94. Acta Paediatr 2001; 90: 271–7.

- Hägglund G, Andersson S, Düppe H, Lauge-Pedersen H, Westbom L. Prevention of dislocation of the hip in children with cerebral palsy: The first ten years of a population-based prevention programme. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005; 87-B: 95–101.

- Hägglund G, Lauge-Pedersen H, Wagner P. Characteristics of children with hip displacement in cerebral palsy. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007; 8: 101.

- Hilgenreiner H. Zur Frühdiagnose und Frühbehandlung der angeborenen Hüftgelenkverrenkung. Med Klin 1925; 21 (38): 1425–9.

- Kalen V, Bleck E E. Prevention of spastic paralytic dislocation of the hip. Dev Med Child Neurol 1985; 27: 17–24.

- Letts M, Shapiro L, Mulder K, Klassen O. The windblown hip syndrome in total body cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop 1984; 4: 55–62.

- Miller F, Dias R C, Dabney K W, Lipton G E, Triana M. Soft-tissue release for spastic hip subluxation in cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop 1997; 17: 571–84.

- Onimus M, Allamel G, Manzone P, Laurain J M. Prevention of hip dislocation in cerebral palsy by early psoas and adductor tenotomies. J Pediatr Orthop 1991; 11: 432–5.

- Palisano R J, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, Wood E, Galuppi B. Development and validation of a gross motor function classification system for children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 1997; 39: 214–23.

- Presedo A, Oh C-W, Dabney K W, Miller F. Soft-tissue releases to treat spastic hip subluxation in children with cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87-A: 832–41.

- Ramstad K, Terjesen T. Hip pain is more frequent in severe hip displacement: A population-based study of 77 children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop B 2016; 25: 217–21.

- Reimers J. The stability of the hip in children. Acta Ortop Scand 1980; 51(Suppl184): 12–91.

- Samilson R L, Tsou P, Aamoth G, Green W. Dislocation and subluxation of the hip in cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1972; 54-A: 863–73.

- Sharrard W J W, Allen J M H, Heaney S H, Prendiville G R G. Surgical prophylaxis of subluxation and dislocation of the hip in cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Br 1975; 57-B: 160–6.

- Shore B J, Yu X, Desai S, Selber P, Wolfe R, Graham H K. Adductor surgery to prevent hip displacement in children with cerebral palsy: The predictive role of the Gross Motor Function Classification System. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94-A: 326–34.

- Soo B, Howard J J, Boyd R N, et al. Hip displacement in cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88-A: 121–9.

- Terjesen T. The natural history of hip development in cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2012; 54: 951–7.

- Terjesen T, Lie G D, Hyldmo Å A, Knaus A. Adductor tenotomy in spastic cerebral palsy: A long-term follow-up study of 78 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 2005; 76: 128–37.

- Turker R J, Lee R. Adductor tenotomies in children with quadriplegic cerebral palsy: Longer term follow-up. J Pediatr Orthop 2000; 20: 370–4.