Abstract

Background and purpose — There is a need to understand the reasons why a high proportion of rotator cuff repairs fail to heal. Using data from a large randomized clinical trial, we evaluated age and tear size as risk factors for failure of rotator cuff repair.

Patients and methods — Between 2007 and 2014, 65 surgeons from 47 hospitals in the National Health Service (NHS) recruited 447 patients with atraumatic rotator cuff tendon tears to the United Kingdom Rotator Cuff Trial (UKUFF) and 256 underwent rotator cuff repair. Cuff integrity was assessed by imaging in 217 patients, at 12 months post-operation. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine the influence of age and intra-operative tear size on healing. Hand dominance, sex, and previous steroid injections were controlled for.

Results — The overall healing rate was 122/217 (56%) at 12 months. Healing rate decreased with increasing tear size (small tears 66%, medium tears 68%, large tears 47%, and massive tears 27% healed). The mean age of patients with a healed repair was 61 years compared with 64 years for those with a non-healed repair. Mean age increased with larger tear sizes (small tears 59 years, medium tears 62 years, large tears 64 years, and massive tears 66 years). Increasing age was an independent factor that negatively influenced healing, even after controlling for tear size. Only massive tears were an independent predictor of non-healing, after controlling for age.

Interpretation — Although increasing age and larger tear size are both risks for failure of rotator cuff repair healing, age is the dominant risk factor.

Rotator cuff tendon tears are very common and are found in around 15–20% of 60-year-olds, 26–30% of 70-year-olds, and 36–50% of 80-year-olds (Tempelhof et al. Citation1999, Minagawa et al. Citation2013). Tendon tears may cause significant pain and loss of function. In patients with persistent symptoms surgical repair is commonly performed. Rotator cuff repair incidence has increased in the United States to over 15 per 103 people (Colvin et al. Citation2012) in 2006, with over 270,000 being performed per annum (Jain et al. Citation2014).

Reported healing rates range from 6% to 100% (Galatz et al. Citation2004, Gumina et al. Citation2012). Interpretation of these studies is confounded by variations in the definition of healing, the time point at which healing is assessed and the imaging modality and method used to assess healing. A recent NIHR Health Technology Assessment program funded a randomized trial of open versus arthroscopic repair (UKUFF trial), which revealed that 40% of repairs fail within 12 months irrespective of the surgical technique used and that a failed repair adversely affected patient outcomes (Carr et al. Citation2015). Confusion also arises when considering prognostic factors that may influence healing following surgical repair. Commonly cited factors are: age (Kim et al. Citation2012b, Lapner et al. Citation2012, Rhee et al. Citation2014, Park et al. Citation2015), tear size (Lapner et al. Citation2012, Ma et al. Citation2012), fatty infiltration of supraspinatus muscle (Charousset et al. Citation2010, Voigt et al. Citation2010), muscle atrophy of supraspinatus (Dwyer et al. Citation2015), muscle-tendon retraction (Oh et al. Citation2010, Chung et al. Citation2011), sex (Collin et al. Citation2015), manual workers (Collin et al. Citation2015), workers’ compensation (Cuff and Pupello Citation2012a), poor compliance with rehabilitation (Ahmad et al. Citation2015), hypercholesterolemia, cigarette smoking (Nho et al. Citation2009), low bone mineral density of the humeral head (Chung et al. Citation2011), local corticosteroid injections, type of repair construct (Pennington et al. Citation2010, Gartsman et al. Citation2013), and use of orthobiologics (Rodeo et al. Citation2012, Weber et al. Citation2013, Jo et al. Citation2015). The factors that are most consistently reported are patient age and tear size.

The primary aim of this study was to determine the influence of age and tear size, determined at surgery, on the healing rate of rotator cuff repair. We hypothesized that age and increasing tear size would both reduce the likelihood of healing. The secondary aim was to determine whether tear size and age were independent risk variables.

Patients and methods

We used data from the UKUFF trial to conduct this study. The UKUFF trial was a multicenter pragmatic clinical effectiveness trial investigating differences between open versus arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using the Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS) at 24 months as the primary endpoint (Carr et al. Citation2015). Our focus in this study, however, was on the influence on healing of age and intraoperative assessment of tear size, as determined by MRI imaging 12 months following surgical repair. Similarly, our intention was to study how age and tear size influence healing irrespective of the method of surgical repair, open or arthroscopic, hence both techniques were grouped together.

Subjects

The UKUFF trial included 47 recruitment centers, all of which were National Health Service (NHS) Hospitals in the United Kingdom. Patients attending an elective outpatient orthopedic clinic because of shoulder pain were screened. 447 patients were randomized to open or arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in a pragmatic multi-center parallel group randomized controlled trial, between November 2007 and February 2012 (Carr et al. Citation2015). The last patient follow-up was completed in December 2013. Patients recruited into the trial were over 50 years old, with a symptomatic, radiologically confirmed, atraumatic, full-thickness rotator cuff tear. For inclusion and exclusion criteria for the UKUFF study, see Carr et al. (Citation2015). 65 surgeons in 47 hospitals performed rotator cuff repair in 256 patients. Patients underwent surgical repair (mini-open or arthroscopic) in the National Health Service (NHS). Patients whom did not have a complete repair, such as those whose tear was irreparable, were not included in the study. At the time of surgery, rotator cuff tear size was recorded into 1 of 4 categories (small, medium, large, and massive). Patients underwent assessment at 2 and 8 weeks by telephone and at 8, 12, and 24 months postoperatively with patient-reported outcomes (the Oxford Shoulder Score (Dawson et al. Citation1996), the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (Roach et al. Citation1991), and the EuroQol5D (Group Citation1990)).

At the 12-month post-surgical repair assessment, patients underwent evaluation of the repair with MRI scan using a standardized protocol or, if MRI was contra-indicated, by high-definition ultrasound performed by an experienced ultrasonographer. All scans were reviewed by a senior musculoskeletal radiologist to determine whether the rotator cuff repair had healed, not healed, or if the imaging findings were inconclusive. A healed repair was defined as one where the supraspinatus tendon remained attached to the proximal humerus, whilst a failure to heal was deemed to be a full-thickness defect of the supraspinatus tendon. Partial-thickness defects seen at the 12-month imaging scan were treated as either healed if low grade, or inconclusive if high grade. 233 patients underwent imaging at 12 months (MRI or US) of which 217 were of sufficient quality to be interpreted. 3 patients had undergone revision rotator cuff repair for a radiologically confirmed failure of healing and were included as repair failures.

Surgical procedure and postoperative rehabilitation

In this pragmatic clinical effectiveness trial surgeons provided the usual care for their patients including method of rotator cuff repair, type of immobilization, and postoperative protocol for rehabilitation. Details of the surgical technique were recorded.

Tear size assessment

Intraoperative assessment of the tear size was used to reduce any potential error from measurements taken from preoperative imaging and to account for any progression of the tear that might have occurred between imaging and surgery. The UKUFF trial report analyzed tear size based on the assessment from preoperative imaging. Surgeons were given education and provided with written information on how to assess tear size intraoperatively. This included schematic drawings of the shapes and sizes for each of the categories. An intraoperative data collection sheet was completed for each case. Small tears were defined as full-thickness defects in the supraspinatus tendon under 1 cm in the anterior–posterior (AP) dimension. Medium tears were defined as full-thickness defects in the supraspinatus tendon only, greater than 1 cm and less than 3 cm in the AP dimension. Large tears involved full-thickness defects of both the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons, greater than 3 cm, and less than 5 cm in the AP dimension. Massive tears involved all 3 tendons (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and subscapularis) and were greater than 5 cm in the AP dimension. All participating surgeons met with the senior author and discussed all aspects of trial involvement including the data collection theatre form (see Supplementary material). All queries were resolved prior to commencement of recruitment.

Statistics

We used logistic regression to evaluate the influence of patient age and intraoperative tear size on structural integrity of rotator cuff repair at 12 months postoperatively in Stata (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Tear size was modeled into 4 groups (small, medium, large, and massive). Age was initially treated as a continuous linear factor (years). Sensitivity of findings, controlling for hand dominance, previous steroid injection, sex, tear size, and age, was assessed. Age was also modeled using a fractional polynomial approach which allowed age to have non-linear shapes. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics, registration, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

This study was approved by the United Kingdom Multicenter Research Ethics Committee (MREC) (Reference: 07/Q1606/49). The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Programme, the Lord Nuffield Trust, and the NIHR Oxford Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Unit. No competing interest declared.

Results

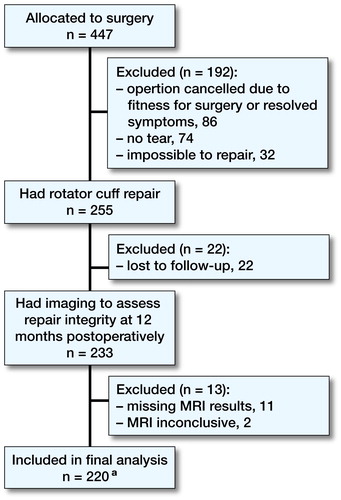

447 patients were randomized to surgery; of these, 255 underwent rotator cuff repair. 86 patients were cancelled whilst waiting for surgery because either their symptoms resolved or they had become medically unfit. At surgery 74 were found to have no tear due to a false-positive scan and in 32 the tear was impossible to repair. We included 3 patients that underwent revision rotator cuff repair before the 12-month MRI scan time point due to radiologically confirmed failure of the primary repair. Of the 255 patients that underwent surgical repair, 230 had a standardized assessment of the repair at 12 months postoperatively of which 13 did not have MRI finding or could not be interpreted due to metal artifact from suture anchors, leaving 220 patients included in the final analysis (.).

Failure rate by tear size

The overall failure to heal rate was 43% (95/220) at 12 months post-surgical repair. For small tears, the failure rate was 34% (20/58) at 12 months. For medium tears the failure rate was 36% (27/75). Just under half (47%, 24/51) of large tears showed an intact repair at the 12-month MRI scan, and 73% (24/33) of massive tears failed to heal.

Relationship between age and tear size

For small tears, the mean age was 59 years, for medium tears 62 years, for large tears 64 years, and for massive tears 66 years. To explore this relationship further, we adjusted for age and tear size in the logistic regression model.

Influence of age on healing rate

Patients with an intact repair tended to be younger (OR 0.94, CI 0.91–0.98, p < 0.01). The logistic regression model demonstrated that age was an independent predictor for a structurally intact rotator cuff repair. The fractional polynomial models incorporating age found a linear relationship sufficient. Following adjustment for tear size, number of corticosteroid injections, sex, and hand dominance, age remained a predictive factor for healing (OR 0.95, CI 0.91–0.999, p = 0.04).

Influence of tear size on healing rate

Increasing tear size was also related to reducing healing rate as noted above. However, we aimed to determine, using a logistic regression model, if age or tear size had a greater influence on the likelihood of a successful repair. Following adjustment for age, number of corticosteroid injections, sex, and hand dominance only massive tears remained a predictive factor for an intact repair at 12 months (OR 0.18, CI 0.05–0.61, p < 0.01). The effect of increasing age seen in larger tears is a confounder: when controlled for in our model, only massive tear size was an independent predictor of healing.

Estimated probability of healing

From a logistic regression model with only age and tear size as predictors, the estimated probability of healing was determined for the patients who were 50, 60, 70 and 80 years old with a small, medium, large, or massive tear. In small and medium tears in 50- and 60-year-olds the predicted healing rate was between 65% and 78% ().

Table 1. Predictive healing (%) for patients according to age with a small, medium, large, or massive rotator cuff tear

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that the overall healing rate at 12 months of 220 operations, performed by 65 surgeons in 47 hospitals, was 57%. A review of the literature reveals that 49 studies have reported an overall healing rate of 68% in patients with average age of 60 years. Of these, 21 studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 1 pilot RCT (Antuña et al. Citation2013), 6 Quasi-randomized Controlled Trial (Arndt et al. Citation2012, Barber et al. Citation2012, Cuff and Pupello Citation2012b, Lee et al. Citation2012, Ma et al. Citation2012, Gartsman et al. Citation2013), 6 prospective cohort studies (Iannotti et al. Citation2006, Ko et al. Citation2008, Charousset et al. Citation2014, Hernigou et al. Citation2014, Boyer et al. Citation2015, Gilot et al. Citation2015), 4 retrospective cohort studies (Tudisco et al. Citation2013, Ciampi et al. Citation2014, Cho et al. Citation2015, Wang et al. Citation2015), 5 case-control studies (J. R. Kim et al. Citation2012a, Robertson et al. Citation2012, Rhee et al. Citation2014, Cho et al. Citation2015, Park et al. Citation2015), 2 prospective case series (Lichtenberg et al. Citation2006, Maqdes et al. Citation2014), and 4 retrospective case series (Galatz et al. Citation2004, Chung et al. Citation2011, Meyer et al. Citation2012, Kerr et al. Citation2015). Of the 28 studies reported as Level 1 evidence, there is still substantial risk of bias, as determined by the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins et al. Citation2011). Whilst RCTs are, in principle, designed to minimize bias from a variety of causes, it is vital that they are conducted and reported correctly to ensure their individual risk of bias is low or very low.

When considering the healing rate of rotator cuff repair from these 28 studies, the pooled weighted healing rate of rotator cuff repair went down from 94% in 2007 to 71% in 2015. The reason for this is likely to be multifactorial. One possibility is publication bias and an increased tendency to report not just clinical outcomes but also imaging of repair integrity post-surgery. In addition, there has been a dramatic increase in the incidence of rotator cuff repair surgery, reflecting a probable change in selection criteria for surgery.

We found that patients with a healed repair tended to be younger. Additionally, small and medium tears were more likely to heal than large and massive tears. At face value it appears that age and tear size are equally important risk factors; however, we have demonstrated that when age is adjusted for in a logistic regression model only massive tears were independently predictive of failure. Park et al. (Citation2015) used a univariate analysis in their case-control study to conclude that both age and tear size were prognostic factors for healing. They also noted that the mean age of patients with healed repairs was 59 vs. 63 years in those with a failed repair and that tears greater than 2 cm in size healed less often than those less than 2 cm (66% vs. 89%). They did not adjust for age and tear size together.

Lapner et al. (Citation2012) found the mean age of those patients with a recurrent tear was 1.8 years older than those with a healed repair (p = 0.5). Mean coronal and sagittal tear size was statistically significantly different between repairs that healed and failed to heal. Rodeo et al. (Citation2012) concluded that at 12 weeks post-repair, 71% of small tears healed compared with 82% of medium tears, and 56% of large tears. Gumina et al. (Citation2012) reported that the mean age of patients with a healed repair was 3.0 years younger than those who had a recurrent tear.

In a case-control study, Rhee et al. (Citation2014) reported the healing rate in 60- to 69-year-olds as 60%, whilst this reduced to 50% in 70- to 79-year-old patients. They also reported a similar reduction in healing rate with increasing tear size (small/medium tears 85%, large tears 44%, and massive tears 24%). 2 further case-control studies (Kim et al. Citation2012a, Robertson et al. Citation2012) concluded that the mean age of patients with healed repairs was 61 and 59 years compared with 63 and 61 years respectively. Kim et al. (Citation2012a) concluded this difference was not significant (p = 0.5), whilst Robertson et al. (Citation2012) made no assessment of the significance of their finding with respect to age. A fourth case-control study concluded the mean age of healed repairs was 59 years compared with 63.2 years in those that failed to heal (p = 0.001) (Park et al. Citation2015).

The potential weakness of the UKUFF study is that, due to its pragmatic design, surgeons were given freedom to diagnose rotator cuff tears using their preferred preoperative imaging modality. A variety of different preoperative imaging systems were used with reporting by different radiologists and standardized assessment of fatty infiltration and atrophy of supraspinatus muscle was not possible (Cho and Rhee Citation2009, Charousset et al. Citation2010, Voigt et al. Citation2010, Dwyer et al. Citation2015). However, in this analysis of the UKUFF trial data we used intraoperative assessment of tear size, which was carefully standardized. Despite reasonable efforts to standardize tear size assessment, some variation between surgeons will nevertheless occur. We feel that reducing tears to 4 defined size categories will improve reliability. Caution must be exercised when interpreting the predictive model, which requires validation in a separate population. We made efforts to standardize the postoperative radiological assessment of healing. A single consultant musculoskeletal radiologist, blinded to the type of surgery performed, reviewed all scans. The accuracy of the postoperative imaging assessment was not measured within the UKUFF study.

Arguably the strength of this study of outcomes of rotator cuff repair is its large size involving 220 patients operated on by 65 surgeons in 47 hospitals. The results represent a real-world evaluation of a commonly performed surgical procedure and are generalizable.

In summary, increasing age negatively influenced healing even after controlling for tear size but only massive tears were an independent risk factor after controlling for age. Clinical decision-making should take into account the overriding importance of increasing age as a risk factor when considering the suitability of rotator cuff surgery for patients. Rates of healing are low even for small tears in younger patients and there is a compelling case to develop new strategies to improve the success of surgery.

AJC: Chief investigator, study design, hypothesis generation, interpretation of data, manuscript editing and preparation, and final approval of the version to be published. JC: acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data. DC: analysis, and interpretation of the data. Revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. SGD, SS: revising the manuscript. CC: acquisition of data for the study. MSR: study design, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript.

Acta thanks Lars Evert Adolfsson and other anonymous reviewers for help with peer review of this study.

- Ahmad S, Haber, M Bokor D J. The influence of intraoperative factors and postoperative rehabilitation compliance on the integrity of the rotator cuff after arthroscopic repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015, 24 (2): 229–35.

- Antuña S, Barco R, Martínez Díez J M, Sánchez Márquez J M. Platelet-rich fibrin in arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears: A prospective randomized pilot clinical trial. Acta Orthop Belg 2013; 79 (1): 25–30.

- Arndt J, Clavert P, Mielcarek P, Bouchaib J, Meyer N, Kempf J F, French Society for S Elbow. Immediate passive motion versus immobilization after endoscopic supraspinatus tendon repair: A prospective randomized study. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2012; 98(6Suppl): S131–S8.

- Barber F A, Burns J P, Deutsch A, Labbe M R, Litchfield R B. A prospective randomized evaluation of acellular human dermal matrix augmentation for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy 2012; 28 (1): 8–15.

- Boyer P, Bouthors C, Delcourt T, Stewart O, Hamida F, Mylle G, Massin P. Arthroscopic double-row cuff repair with suture-bridging: A structural and functional comparison of two techniques. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015; 23 (2): 478–86.

- Carr A J, Cooper C D, Campbell M K, Rees J L, Moser J, Beard D J, Fitzpatrick R, Gray A, Dawson J, Murphy J, Bruhn H, Cooper D, Ramsay C R. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of open and arthroscopic rotator cuff repair [the UK rotator cuff surgery (UKUFF) randomised trial]. Health Technol Assess 2015 19 (80): 1–218.

- Charousset C, Bellaiche L, Kalra K, Petrover D. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness rotator cuff tears: Is the;re tendon healing in patients aged 65 years or older? Arthroscopy 2010 26 (3): 302–9.

- Charousset C, Zaoui A, Bellaiche L, Piterman M. Does autologous leukocyte-platelet-rich plasma improve tendon healing in arthroscopic repair of large or massive rotator cuff tears? Arthroscopy 2014; 30 (4): 428–35.

- Cho N S, Rhee Y G. The factors affecting the clinical outcome and integrity of arthroscopically repaired rotator cuff tears of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Surg 2009; 1 (2): 96–104.

- Cho N S, Moon S C, Jeon J W, Rhee Y G. The influence of diabetes mellitus on clinical and structural outcomes after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med 2015 43 (4): 991–7.

- Chung S W, Oh J H, Gong H S, Kim J Y, Kim S H. Factors affecting rotator cuff healing after arthroscopic repair: Osteoporosis as one of the independent risk factors. Am J Sports Med 2011; 39 (10): 2099–107.

- Ciampi P, Scotti C, Nonis A, Vitali M, Di Serio C, Peretti G M, Fraschini G. The benefit of synthetic versus biological patch augmentation in the repair of posterosuperior massive rotator cuff tears: A 3-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med 2014; 42 (5): 1169–75.

- Collin P, Abdullah A, Kherad O, Gain S, Denard P J, Ladermann A. Prospective evaluation of clinical and radiologic factors predicting return to activity within 6 months after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015; 24 (3): 439–45.

- Colvin A C, Egorova N, Harrison A K, Moskowitz A, Flatow E L. National trends in rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94 (3): 227–33.

- Cuff D J, Pupello D R. Prospective evaluation of postoperative compliance and outcomes after rotator cuff repair in patients with and without workers’ compensation claims. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012a; 21 (12): 1728–33.

- Cuff D J, Pupello D R. Prospective randomized study of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using an early versus delayed postoperative physical therapy protocol. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012b; 21 (11): 1450–5.

- Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about shoulder surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996; 78 (4): 593–600.

- Dwyer T, Razmjou H, Henry P, Gosselin-Fournier S, Holtby R. Association between pre-operative magnetic resonance imaging and reparability of large and massive rotator cuff tears, Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015; 23 (2): 415–22.

- Galatz L M, Ball C M, Teefey S A, Middleton W D, Yamaguchi K. The outcome and repair integrity of completely arthroscopically repaired large and massive rotator cuff tears, J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004; 86-A (2): 219–24.

- Gartsman G M, Drake G, Edwards T B, Elkousy H A, Hammerman S M, O’Connor D P, Press C M. Ultrasound evaluation of arthroscopic full-thickness supraspinatus rotator cuff repair: Single-row versus double-row suture bridge (transosseous equivalent): fixation. Results of a prospective randomized study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2013; 22 (11): 1480–7.

- Gilot G J, Alvarez-Pinzon A M, Barcksdale L, Westerdahl D, Krill M, Peck E. Outcome of large to massive rotator cuff tears repaired with and without extracellular matrix augmentation: A prospective comparative study, Arthroscopy 2015; 31 (8): 1459–65.

- Group T E. Euroqol*: A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990; 16: 199–208.

- Gumina S, Campagna V, Ferrazza G, Giannicola G, Fratalocchi F, Milani A, Postacchini F. Use of platelet-leukocyte membrane in arthroscopic repair of large rotator cuff tears: A prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94 (15): 1345–52.

- Hernigou P, Flouzat Lachaniette C H, Delambre J, Zilber S, Duffiet P, Chevallier N, Rouard H. Biologic augmentation of rotator cuff repair with mesenchymal stem cells during arthroscopy improves healing and prevents further tears: A case-controlled study. Int Orthop 2014; 38 (9): 1811–18.

- Higgins J P, Altman D G, Gotzsche P C, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman A D, Savovic J, Schulz K F, Weeks L, Sterne J A, Cochrane Bias Methods G, Cochrane Statistical Methods G. The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011; 343: d5928.

- Iannotti J P, Codsi M J, Kwon Y W, Derwin K, Ciccone J, Brems J J. Porcine small intestine submucosa augmentation of surgical repair of chronic two-tendon rotator cuff tears: A randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88 (6): 1238–44.

- Jain N B, Higgins L D, Losina E, Collins J, Blazar P E, Katz J N. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal upper extremity ambulatory surgery in the United States. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014; 15: 4.

- Jo C H, Shin J S, Shin W H, Lee S Y, Yoon K S, Shin S. Platelet-rich plasma for arthroscopic repair of medium to large rotator cuff tears: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 2015; 43 (9): 2102–10.

- Kerr J, Borbas P, Meyer D C, Gerber C, Buitrago Tellez C, Wieser K. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in the weight-bearing shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015; 24 (12): 1894–9.

- Kim J R, Cho Y S, Ryu K J, Kim J H. Clinical and radiographic outcomes after arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears using a suture bridge technique: Assessment of repair integrity on magnetic resonance imaging, Am J Sports Med 2012a; 40 (4): 786–93.

- Kim Y S, Chung S W, Kim J Y, Ok J H, Park I, Oh J H. Is early passive motion exercise necessary after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair? Am J Sports Med 2012b; 40 (4): 815–21.

- Ko S H, Lee C C, Friedman D, Park K B, Warner J J. Arthroscopic single-row supraspinatus tendon repair with a modified mattress locking stitch: A prospective randomized controlled comparison with a simple stitch. Arthroscopy 2008; 24 (9): 1005–12.

- Lapner P L, Sabri E, Rakhra K, McRae S, Leiter J, Bell K, Macdonald P. A multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing single-row with double-row fixation in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94 (14): 1249–57.

- Lee B G, Cho N S, Rhee Y G. Effect of two rehabilitation protocols on range of motion and healing rates after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: Aggressive versus limited early passive exercises, Arthroscopy 2012; 28 (1): 34–42.

- Lichtenberg S, Liem D, Magosch P, Habermeyer P. Influence of tendon healing after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair on clinical outcome using single-row Mason-Allen suture technique: A prospective MRI controlled study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2006; 14 (11): 1200–6.

- Ma H L, Chiang E R, Wu H T, Hung S C, Wang S T, Liu C L, Chen T H. Clinical outcome and imaging of arthroscopic single-row and double-row rotator cuff repair: A prospective randomized trial. Arthroscopy 2012; 28 (1): 16–24.

- Maqdes A, Abarca J, Moraiti C, Boughebri O, Dib C, Leclere F M, Kany J, Elkolti K, Garret J, Katz D, Valenti P. Does preoperative subscapularis fatty muscle infiltration really matter in anterosuperior rotator cuff tears repair outcomes? A prospective multicentric study. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2014; 100 (5): 485–8.

- Meyer M, Klouche S, Rousselin B, Boru B, Bauer T, Hardy P. Does arthroscopic rotator cuff repair actually heal? Anatomic evaluation with magnetic resonance arthrography at minimum 2 years follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012; 21 (4): 531–6.

- Minagawa H, Yamamoto N, Abe H, Fukuda M, Seki N, Kikuchi K, Kijima H, Itoi E. Prevalence of symptomatic and asymptomatic rotator cuff tears in the general population: From mass-screening in one village. J Orthop 2013; 10 (1): 8–12.

- Nho S J, Shindle M K, Adler R S, Warren R F, Altchek D W, MacGillivray J D. Prospective analysis of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: Subgroup analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2009; 18 (5): 697–704.

- Oh J H, Kim S H, Kang J Y, Oh C H, Gong H S. Effect of age on functional and structural outcome after rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med; 2010 38 (4): 672–8.

- Park J S, Park H J, Kim S H, Oh J H. Prognostic factors affecting rotator cuff healing after arthroscopic repair in small to medium-sized tears. Am J Sports Med 2015; 43 (10): 2386–92.

- Pennington W T, Gibbons D J, Bartz B A, Dodd M, Daun J, Klinger J, Popovich M, Butler B. Comparative analysis of single-row versus double-row repair of rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy 2010; 26 (11): 1419–26.

- Rhee Y G, Cho N S, Yoo J H. Clinical outcome and repair integrity after rotator cuff repair in patients older than 70 years versus patients younger than 70 years. Arthroscopy 2014; 30 (5): 546–54.

- Roach K E, Budiman-Mak E, Songsiridej N, Lertratanakul Y. Development of a shoulder pain and disability index. Arthritis Care Res 1991; 4 (4): 143–9.

- Robertson C M, Chen C T, Shindle M K, Cordasco F A, Rodeo S A, Warren R F. Failed healing of rotator cuff repair correlates with altered collagenase and gelatinase in supraspinatus and subscapularis tendons. Am J Sports Med 2012; 40 (9): 1993–2001.

- Rodeo S A, Delos D, Williams R J, Adler R S, Pearle A, Warren R F. The effect of platelet-rich fibrin matrix on rotator cuff tendon healing: A prospective randomized clinical study. Am J Sports Med; 2012 40 (6): 1234–41.

- Tempelhof S, Rupp S, Seil R. Age-related prevalence of rotator cuff tears in asymptomatic shoulders. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1999; 8 (4): 296–9.

- Tudisco C, Bisicchia S, Savarese E, Fiori R, Bartolucci D A, Masala S, Simonetti G. Single-row vs. double-row arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: Clinical and 3 tesla MR arthrography results. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013; 14: 43.

- Voigt C, Bosse C, Vosshenrich R, Schulz A P, Lill H. Arthroscopic supraspinatus tendon repair with suture-bridging technique: Functional outcome and magnetic resonance imaging, Am J Sports Med 2010; 38 (5): 983–91.

- Wang E, Wang L, Gao P, Li Z, Zhou X, Wang S. Single-versus double-row arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in massive tears. Med Sci Monit 2015; 21: 1556–61.

- Weber S C, Kauffman J I, Parise C, Weber S J, Katz S D. Platelet-rich fibrin matrix in the management of arthroscopic repair of the rotator cuff: A prospective randomized double-blinded study. Am J Sports Med 2013; 41 (2): 263–70.