Abstract

Background and purpose — The treatment of patients between 55 and 70 years with displaced intracapsular femoral neck fracture remains controversial. We compared internal fixation (IF), bipolar hemiarthroplasty (HA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA) in terms of mortality, reoperations and patient-reported outcome by using data from the Norwegian Hip Fracture Register.

Patients and methods — We included 2,713 patients treated between 2005 and 2012. 1,111 patients were treated with IF, 1,030 with HA and 572 patients with THA. Major reoperations (defined as re-osteosynthesis, secondary arthroplasty, exchange, or removal of prosthesis components and Girdlestone procedure), patient-reported outcome measures (satisfaction, pain, and health-related quality of life (EQ5D) after 4 and 12 months), 1-year mortality, and change in treatment methods over the study period were investigated.

Results — Major reoperations occurred in 27% after IF, 3.8% after HA and 2.8% after THA. 549 patients (20% of total study population) answered both questionnaires. Compared with IF, patients treated with THA were more satisfied after 4 and 12 months, reported less pain after 4 months and 12 months, had a higher EQ5D-index score after 4 months and 12 months, and EQ-VAS score after 4 months. Compared with IF, patients treated with HA were more satisfied and reported less pain after 4 months. EQ5D-index and EQ-VAS were similar. Patients treated with HA had higher 1-year mortality and had more comorbidities than both the THA and IF group. All these differences were statistically and clinically significant.

Interpretation — This study showed high reoperation rate after IF and better patient-reported outcome after both THA and HA with medium follow-up. Patients selected for HA represented a frailer group than patients treated with THA or IF.

The treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures (FNFs) in old and frail patients has been thoroughly investigated in the literature and most studies have advocated arthroplasty as the treatment of choice (Gjertsen et al. Citation2010, Dai et al. Citation2011, Støen et al. Citation2014). For patients between 55 and 70 years, however, little research exists, rendering the choice of treatment a challenge. Most FNFs in these relatively young individuals occur as a result of a low-energy trauma, and the patients often have other diseases and conditions that may increase the risk of failed IF, such as medication (steroids, anti-epileptic medication), alcoholism, other substance abuse, and osteoporosis (Lofthus et al. Citation2006, Karantana et al. Citation2011, Al-Ani et al. Citation2013). However, closed reduction and IF for patients under 60 years of age is usually recommended as many surgeons are reluctant to replace a native hip joint with an arthroplasty (Bhandari et al. Citation2005, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Citation2011, Roberts and Brox Citation2015). IF is less invasive than prosthetic surgery, but the risk of reoperation due to mechanical failure, non-union, or avascular necrosis is high (Upadhyay et al. Citation2004). Furthermore, when an arthroplasty is performed due to failure of internal fixation, the risk of complications is higher and both hip function and quality of life might be inferior, compared with that after primary arthroplasty (Blomfeldt et al. Citation2006, Frihagen et al. Citation2007).

Therefore we compared different surgical treatment methods with respect to reoperation, patient-reported outcome (pain, satisfaction, and health-related quality of life), and mortality in patients between 55 and 70 years with displaced FNFs.

Patients and methods

The nationwide Norwegian Hip Fracture Register (NHFR) was initiated in 2005 and aim to collect data from all hip fracture operations performed in Norway (Gjertsen et al. Citation2008). We present data on patients aged 55-70 years reported to the NHFR with displaced femoral neck fractures treated with IF, HA or THA.

After each operation, patient-and operative data were recorded by the surgeon and reported to the register (Gjertsen et al. Citation2008). Cognitive impairment was recorded according to the clinical evaluation of the orthopedic surgeon but only to the NHFR. Comorbidity was reported as ASA class. Mortality data were obtained from Statistics Norway. Compared with the Norwegian Patient Registry, the NHFR has a completeness of primary operations of 89% (Havelin et al. Citation2016). FNFs treated primarily with a THA and secondary THAs due to failure of the primary procedure were reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) and information from these operations was included in the files of the NHFR before analyses were performed. Information on cognitive impairment was not reported for these patients.

All reoperations were linked to their index operation by use of the national identification number. A reoperation in the NHFR is defined as any type of secondary surgery, including closed reduction of dislocated hemiarthroplasties, soft tissue debridement and reoperation converting to HA or THA. For THAs reported to the NAR only reoperations including exchange or removal of one or more prosthesis components were reported. Closed reduction of dislocated THAs and soft tissue debridement of infected THAs without exchange or removal of components were not recorded. Analyses with all registered reoperations as endpoint were thus not comparable. We therefore classified reoperations into minor or major. Minor reoperations included removal of hardware after healed fracture, closed reduction of a dislocated HA and soft tissue debridement without exchange or removal of components. A major reoperation after IF was any re-osteosynthesis, reoperation with a secondary HA or THA, and Girdlestone procedures. Major reoperation after HA and THA was exchange or removal of one or more prosthesis components.

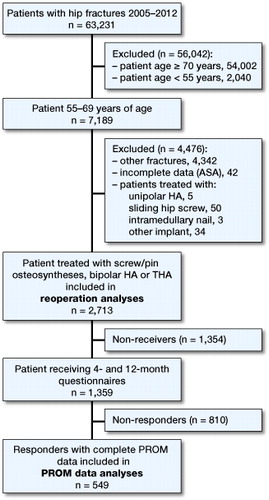

The register sent questionnaires to patients at 4 and 12 months after surgery (Gjertsen et al. Citation2008). These questionnaires contained a visual analog scale (VAS) assessing the average level of pain from the operated hip within the last month (0 indicated no pain and 100 indicated unbearable pain) and a VAS concerning satisfaction with the result of the operation (0 indicated very satisfied and 100 indicated very unsatisfied). Furthermore, the questionnaires included the Norwegian translated form of the EQ-5D-3L and the visual analog scale (EQ-VAS). The preference scores (EQ-5D index scores) generated from a large European population were used (Greiner et al. Citation2003). The EQ-VAS is a 20-cm visual analog scale ranging from 0 (indicating worst possible health) to 100 (indicating best possible health). All patients fulfilling inclusion criteria in the period January 2005–December 2012 were included ().

Of the 2,713 patients included in the study, 1,354 did not receive 1 or both of the questionnaires (non-receivers), because they were dead at the time of follow-up or because the registry for a limited period due to economic reasons sent questionnaires only to a random selection of patients. 1,359 patients received both the 4 and 12 months questionnaire (receivers) (see ) with a response rate of 71% and 59% respectively. 810 patients, who did not respond to 1 or both questionnaires (non-responders) or who returned incomplete questionnaires, were excluded from the PROM (patient reported outcome measures) data analyses. No reminders were sent.

Finally, 2,713 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria and 549 patients had completed both the 4 and 12 months questionnaires, and were included in the PROM analyses.

Statistics

We used the Pearson chi-square test for comparison of categorical variables and Student’s t-test for comparison of continuous variables in independent groups. 1-year mortality was calculated with Kaplan–Meier analyses. A Cox regression analysis with adjustment for age group (55–59 years, 60–64 years, 65–69 years), sex, and ASA grade was used to calculate relative risk for death within 1 year, and to calculate survival curves and hazard rate ratios (HHRs) for reoperations in different treatment groups. Since the definitions of reoperations were different in the NHFR and the NAR only major reoperations were included in the regression analyses. The proportional hazards assumption was fulfilled when evaluated visually by use of log-minus-log plot. Since death is a competing risk, and hence influences the accumulated probability for revision, regression analyses for competing risk were performed. The Fine and Gray regression model for the sub-hazard was applied to calculate subHRRs. These results were compared with the results from the Cox proportional hazards regression model. As the proportion of patients with bilateral operations was negligible in our study (1.6%), both operations were included in the analyses. Continuous variables are presented as mean values (SD). Tests were 2-sided and results were considered significant at the 5% level. The analyses were performed using IBM-SPSS, version 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) and the cmprsk Library in the statistical package R (http://CRAN.R-project.org/Package=cmprsk<http://cran.rproject.org/Package=cmprsk>).

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

The NHFR has permission from the Norwegian Data Inspectorate to collect patient data based on written consent from the patients (permission issued January 3, 2005; reference number 2004/1658-2 SVE/-). Informed consent from patients was entered in the medical records at each hospital. The Norwegian Hip Fracture Register is financed by the Western Norway Regional Health Authority (Helse-Vest). The first author receives funding from Strategic Research funding Akershus University Hospital and from Sophies Minde Ortopedi AS, a subsidiary of Oslo University Hospital and Akershus University Hospital. No competing interests were declared.

Results

Study population

As of December 31, 2012, 2,805 primary operations for displaced FNFs in patients aged 55–70 years were registered in the NHFR. 92 patients treated with rarely used implants were excluded (see ) and the remaining 2,713 patients were included in the study. 43 of these patients had bilateral operations during the follow-up. Thus, 2,713 fractures in 2,670 individual patients were included.

Demographic analyses

1,111 patients were treated with IF, 1,030 patients with bipolar HA, and 572 patients were treated with a THA. Patients treated with HA were older and had more comorbidity, compared with the other groups. There were more patients with cognitive impairment in the HA group, compared with the patients treated with IF ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics according to different operation types

Implants

Olmed screws (DePuy, Raynham, MA, USA) were the most common implant in the IF group. The cemented Exeter/V40 prosthesis (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI, USA) and the uncemented Corail stem (DePuy) were the most commonly used femoral stems (Table 2, see Supplementary data).

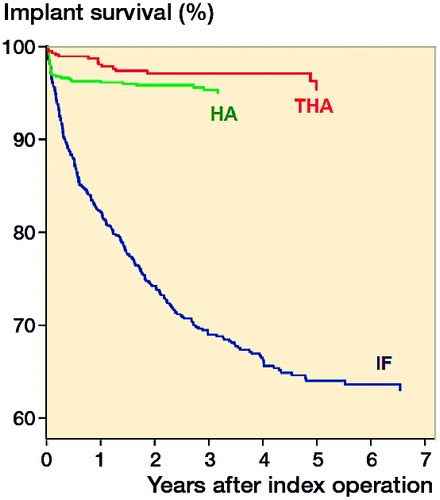

Reoperations

369 patients (33%) in the IF group and 54 patients (5.2%) in the HA group had at least 1 reoperation during the follow-up period. 16 patients (2.8%) in the THA group underwent a subsequent revision of the prosthesis (with removal or exchange of prosthesis components) (). Minor procedures after IF included removal of implants (n = 63) and soft tissue debridement for hematoma (n = 1). Minor procedures after HA included soft tissue debridement for hematoma or infection (n = 8), closed reduction of dislocated HA (n = 6), and open reduction for dislocated HA (n = 1).

Table 3. Numbers and types of major reoperations

When excluding the minor procedures, the rate of major reoperation was 27% (305 out of 1,111 patients) for the IF patients and 3.8% (39 out of 1,030) for the HA patients. After adjusting for age group, sex, and ASA grade in a Cox regression model HA had a similar risk of major reoperation as THA (HRR 1.4 (95% CI 0.77–2.5). HRR for major reoperation for IF vs. THA was 11 (95% CI 6.8–19) (). Further, competing risk analyses with adjustments for age group, sex, and ASA, subHRR for HA vs. THA, was 1.4 (95% CI 0.80–2.6) and subHRR for IF vs. THA was 12 (95% CI 7.3–20).

Patient-reported outcome analyses

These analyses comprise the 549 patients who responded to both questionnaires (20% of the total study population). The responders were healthier according to the ASA classification compared with the non-responders (Table 4, see Supplementary data).

More patients treated with internal fixation and fewer patients treated with arthroplasty responded to the questionnaires. Responders treated with HA were older and had more comorbidity in terms of higher ASA grade compared with patients treated with IF and HA (Table 5, see Supplementary data).

Patients treated with HA or THA were more satisfied with the result of the operation and reported less pain after both 4 and 12 months follow-up than patients treated with IF (). The patients treated with THA reported statistically significantly higher EQ-5D index score at both 4 and 12 months follow-up and a statistically significant higher EQ-VAS after 4 months than patients in the IF group.

Table 6. PROM results for responders

Mortality

The crude 1-year mortality was 6.3% (70/1,111) after IF, 15% (155/1,030) after HA, and 4.2% (24/572) after THA. With adjustment for age, sex, and ASA classification patients treated with HA had a higher 1-year mortality compared with patients treated with a THA (HRR 2.3, 95% CI 1.5–5.5). No statistically significant difference in 1-year mortality was found between patients treated with IF and THA (HRR 1.4, 95% CI 0.85–2.2).

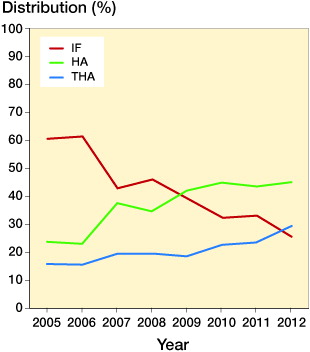

Time change

There was a change over time of treatment for displaced femoral neck fractures (). The percentage of patients treated with IF declined from 60% (115 patients out of 190) in 2005 to 25% (101/395) in 2012. HA and THA increased from 24% (45/190) to 45% (178/395) and 16% (30/190) to 29% (116/395) respectively. The number of major reoperations after internal fixation was 36 (31%) in 2005 and 24 (19%) in 2011. The year of surgery did not statistically significantly influence the risk of major reoperation when performing a Cox regression analysis with adjustments for age group, sex, and ASA class (p = 0.3).

Discussion

Treatment with IF for displaced femoral neck fractures led to a high rate of reoperations in this population of relatively young patients; more than 1 out of 4 patients underwent a reoperation after IF. Patients treated with HA or THA were significantly more satisfied and reported less pain. Patients treated with THA or IF were the most comparable groups based on comorbidities, and our findings favored THA also in these younger patients. This is in accordance with previous studies on elderly patients with femoral neck fractures (Leonardsson et al. Citation2013). Interestingly, even though the HA group was frailer than the IF group, there were better results with arthroplasty for these patients also. The difference between HA and THA was not of statistical or clinical importance, either regarding number of major reoperations or in patient satisfaction. This may indicate that the surgeons have chosen patients in need of either arthroplasty wisely.

Compared with a randomized controlled trial a register-based observational study has some limitations. Differences in baseline characteristics of the groups may render comparisons less valid. Focusing on the more homogeneous groups with IF and THA, and adjustment for age, sex, and ASA grade are ways to deal with these limitations.

A strength of our study is the large number of patients included. The percentage of patients categorized as healthy (ASA grade I) was quite similar in the IF group and the THA group, but patients in the HA group had more comorbidities. Assumingly the surgeons regard these patients as 2 distinct groups, either “biologically old” and treated mainly with a HA, or relatively fitter and treated with IF or THA, with THA on the increase recently. This is reasonable: the relatively fittest patients may benefit from a THA (Parker and Gurusamy Citation2006, Baker et al. Citation2006). The use of HA in the frailest of the younger hip fracture patients in our study may be supported by several meta-analyses recommending HA for older patients with impaired general conditions or institutionalized patients (Rogmark and Johnell Citation2006, He et al. Citation2012). The rate of reoperation we found is comparable to previously reported results in patients older than 70 years (Rogmark and Leonardsson Citation2016).

1 out of 5 patients between 55 and 70 years was treated with a total hip replacement. During the study period, however, there was a marked shift from the use of internal fixation to arthroplasties, both HA and THA. This is similar to the shift in the treatment observed for elderly patients (Støen et al. Citation2014). The reason for this might also be that surgeons have changed practice as a result of newer knowledge, such as effects of posterior tilt (Palm et al. Citation2009, Dolatowski et al. Citation2016) and outcome of frailer patients treated with HA (Rogmark and Leonardsson Citation2016).

Indication for surgery and the treatment were decided by the surgeons. We had neither information on the experience level of the surgeons performing the surgery nor postoperative radiographs available. Accordingly, the quality of the surgery could not be studied. The results, in particular for the IF group, may have been better if only experienced surgeons performed the operations. On the other hand, they present the nationwide everyday results that are achieved by an average orthopedic surgeon.

We have no exact data on the completeness of reported complications. We are aware of some underreporting of reoperations, but we have no reason to suspect that different treatment methods had different rates of reporting. We tried to compensate for the fact that secondary surgery is differently defined in the NHFR and NAR by focusing on major reoperations only, regardless of method (Gjertsen et al. Citation2007, Gundtoft et al. Citation2016).

The patient questionnaires had a relatively low response rate. The baseline characteristics between receivers and non-receivers of the questionnaires showed that age and sex did not differ between the treatment groups. However, the responders were healthier than the non-responders and the non-receivers. Hence, the PROM results should be interpreted with caution. On the other hand, we are not aware of any hip fracture register gathering PROM data nationwide, meaning that our data provide a unique source of information.

The follow-up was limited to 1 year. Some concern has been raised that hemiarthroplasties in particular may be prone to late complications, such as poor outcome, pain, and acetabular wear. This does not, however, seem to be the case when modern implants are used (Gjertsen et al. Citation2007, CitationFigved et al. 2012, Langset et al. Citation2014, Støen et al. Citation2014). Long-terms results are nevertheless warranted, especially for the healthier patients (Rogmark and Johnell Citation2006, Leonardsson et al. Citation2013, Støen et al. Citation2014).

Randomized trials may be difficult to perform in these patients, as they are a heterogeneous group and relatively few patients below 70 sustain a FNF, but will help in the decision-making. Studies describing more defined subgroups of patients regarding functional demands and comorbidities, and with a longer follow-up, reporting both surgical complications and outcome after 5 to 10 years are also needed.

In summary, treatment with IF resulted in a high number of reoperations.

With fewer reoperations, better patient satisfaction, less pain, and better quality of life, the patients treated with THA had better results than patients treated with IF at both 4 and 12 months postoperatively. Patients treated with HA had, compared with IF, better patient-reported outcome after 4 months, but not after 12 months. Nevertheless, with fewer reoperations it might be a good alternative for the frailest patients. Our results suggest that patients with displaced intracapsular femoral neck fractures between 55 and 70 years of age benefit from treatment with arthroplasty.

Supplementary data

Tables 2, 4, and 5 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1376514

We thank the orthopedic surgeons in Norway for loyally reporting data on hip fracture operations to the NHFR. We acknowledge Eva Dybvik and Anne Marie Fenstad for statistical help.

Our study was planned and designed by all authors. JEG performed the statistical analyses. SB wrote the manuscript. All authors participated in the interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript.

IORT_A_1376514_SUPP.PDF

Download PDF (26.3 KB)- Al-Ani A N, Neander G, Samuelsson B, Blomfeldt R, Ekström W, Hedström M. Risk factors for osteoporosis are common in young and middle-aged patients with femoral neck fractures regardless of trauma mechanism. Acta Orthop. 2013; 84 (1): 54–9.

- Baker R P, Squires B, Gargan M F, Bannister G C. Total hip arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty in mobile, independent patients with a displaced intracapsular fracture of the femoral neck: A randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006: 88: 2583–9.

- Bhandari M, Devereaux P J, Tornetta P 3rd, Swiontkowski M F, Berry D J, Haidukewych G, Schemitsch E H, Hanson B P, Koval K, Dirschl D, Leece P, Keel M, Petrisor B, Heetveld M, Guyatt G H. Operative management of displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients: An international survey. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005; 87: 2122–30.

- Blomfeldt R, Törnkvist H, Ponzer S, Söderqvist A, Tidermark J. Displaced femoral neck fracture: comparison of primary total hip replacement with secondary replacement after failed internal fixation: A 2-year follow-up of 84 patients. Acta Orthop 2006: 77 (4): 638–43.

- Dai Z, Li Y, Jiang D. Meta-analysis comparing arthroplasty with internal fixation for displaced femoral neck fracture in the elderly. J Surg Res 2011; 165 (1): 68–74.

- Dolatowski F C, Adampour M, Frihagen F, Stavem K, Utvåg S E, Hoelsbrekken S E. Preoperative posterior tilt of at least 20° increased the risk of fixation failure in Garden-I and -II femoral neck fractures. Acta Orthop 2016; 87 (3): 252–6.

- Figved W, Dahl J, Snorrason F, Frihagen F, Röhrl S, Madsen J E, Nordsletten L. Radiostereometric analysis of hemiarthroplasties of the hip: A highly precise method for measurements of cartilage wear. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2012; 20 (1): 36–42.

- Frihagen F, Madsen J E, Aksnes E, Bakken H N, Maehlum T, Walløe A, Nordsletten L. Comparison of re-operation rates following primary and secondary hemiarthroplasty of the hip. Injury 2007; 38 (7): 815–19.

- Gjertsen J E, Lie S A, Fevang J M, Havelin L I, Engesaeter L B, Vinje T, Furnes O. Total hip replacement after femoral neck fractures in elderly patients: Results of 8,577 fractures reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, Acta Orthop 2007: 78: 491–7.

- Gjertsen J E, Engesaeter L B, Furnes O, Havelin L I, Steindal K, Vinje T, Fevang J M. The Norwegian Hip Fracture Register: Experiences after the first 2 years and 15,576 reported operations. Acta Orthop 2008; 79: 583–93.

- Gjertsen J E, Vinje T, Engesaeter L B, Lie S A, Havelin L I, Furnes O, Fevang J M. Internal screw fixation compared with bipolar hemiarthroplasty for treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2010: 92: 619–28.

- Greiner W, Weijnen T, Nieuwenhuizen M, Oppe S, Badia X, Busschbach J, Buxton M, Dolan P, Kind P, Krabbe P, Ohinmaa A, Parkin D, Roset M, Sintonen H, Tsuchiya A, de Charro F. A single European currency for EQ-5D health states: Results from a six-country study. Eur J Health Econ 2003: 4 (3): 222–31.

- Gundtoft P H, Pedersen A B, Schønheyder H C, Overgaard S. Validation of the diagnosis “prosthetic joint infection” in the Danish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Bone Joint J 2016; 98-B (3): 320–5.

- Havelin L I, Furnes O, Engesaeter L E, Fenstad A M, Bartz-Johannessen C, Dybvik E, Fjeldsgaard K, Gundersen T. The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register Annual Report 2016. ISBN 978-82-91847-21-4, ISSN: 1893-8906 (printed version), 1893-8914 (online).

- He J H, Zhou C P, Zhou Z K, Shen B, Yang J, Kang P D, Pei F X. Meta-analysis comparing total hip arthroplasty with hemiarthroplasty in the treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures in patients over 70 years old. Chin J Traumatol 2012; 15 (4): 195–200.

- Karantana A, Boulton C, Bouliotis G, Shu K S, Scammell B E, Moran C G. Epidemiology and outcome of fracture of the hip in women aged 65 years and under: A cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011; 93 (5): 658–64.

- Langset E, Frihagen F, Opland V, Madsen J E, Nordsletten L, Figved W. Cemented versus uncemented hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures: 5-year follow up of a randomized trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472: 1291–9.

- Leonardsson O, Rolfson O, Hommel A, Garellick G, Åkesson K, Rogmark C. Patient-reported outcome after displaced femoral neck fracture: A national survey of 4467 patients. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2013: 95: 1693–9.

- Lofthus C M, Osnes E K, Meyer H E, Kristiansen I S, Nordsletten L, Falch J A. Young patients with hip fracture: A population-based study of bone mass and risk factors for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 2006; 17 (11): 1666–72.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hip fracture management (Clinical guideline CG-124) 2011. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG124

- Palm H, Gosvig K, Krasheninnikoff M, Jacobsen S, Gebuhr P. A new measurement for posterior tilt predicts reoperation in undisplaced femoral neck fractures: 113 consecutive patients treated by internal fixation and followed for 1 year. Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (3): 303–7.

- Parker M J, Gurusamy K. Internal fixation versus arthroplasty for intracapsular proximal femoral fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006: nr. 4: CD001708.

- Roberts K C, Brox W T. AAOS clinical practice guideline: Management of hip fractures in the elderly. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2015; 23 (2): 138–40.

- Rogmark C, Johnell O. Primary arthroplasty is better than internal fixation of displaced femoral neck fractures: A meta-analysis of 14 randomized studies with 2289 patients. Acta Orthop 2006; 77 (3): 359–67.

- Rogmark C, Leonardsson O. Hip arthroplasty for the treatment of displaced fractures of the femoral neck in elderly patients. Bone Joint J 2016; 98-B (3): 291–7.

- Støen R Ø, Lofthus C M, Nordsletten L, Madsen J E, Frihagen F. Randomized trial of hemiarthroplasty versus internal fixation for femoral neck fractures: No differences at 6 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472: 360–7.

- Upadhyay A, Jain P, Mishra P, Maini L, Gautum V K, Dhaon B K. Delayed internal fixation of fractures of the neck of the femur in young adults: A prospective, randomized study comparing closed and open reduction. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2004; 86 (7): 1035–40.