Abstract

Background and purpose — The loss of bone mineral in the proximal femur following hip arthroplasty may increase the fracture risk around uncemented stems. We hypothesized that the surgical approach to the hip might influence bone mineral changes around the femoral stem in patients with a femoral neck fracture (FNF).

Patients and methods — This was a pre-specified subgroup analysis (n = 51) of an ongoing randomized trial (n = 120) in patients with FNF. Participants were allocated to an uncemented hemiarthroplasty inserted through a direct lateral (Hardinge) approach or an anterolateral (modified Watson-Jones) approach. The 51 patients (mean age 83 (70–90) years, 33 women) were measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) to assess changes in periprosthetic bone mineral density (BMD).

Results — The mean change in total BMD differed between groups at 12 months in favor of the anterolateral group (4.8%, 95% CI 0.0–9.6; p = 0.05). DXA at 3 months displayed BMD loss in the proximal Gruen zones in the lateral group compared with the anterolateral group. Zone 1 (–5.0% vs. 2.7%), zone 2 (–4.3% vs. 4.1%), zone 6 (–6.5% vs. 0.0%) and zone 7 (–11% vs. –2.4%, all p < 0.05).

Interpretation — DXA measurements in this study indicate that surgical approach to the hip influences periprosthetic BMD. Clinical implications remain uncertain. Our conclusions should be interpreted with caution as we did not perform adjustments for multiple tests, possibly leading to inflation of false-positive findings.

Progressive periprosthetic bone loss around the femoral component is believed to contribute to aseptic loosening (Malchau et al. Citation1993) and late- occurring fractures around the implant (Lindahl Citation2007, Langslet et al. Citation2014). Periprosthetic fractures have emerged as a major reason for revision, especially in the elderly (Thien et al. Citation2014).

Numerous reasons are believed to be responsible for changes in bone mass. Stem design seems to affect bone loss (Karrholm et al. Citation2002, Grant et al. Citation2005, Salemyr et al. Citation2015) as well as stem sizes. It may be that daily activity, sex, and BMI influences BMD changes around the stem (Hayashi et al. Citation2012). Bone loss seems to be an inevitable event after stem insertion as part of the induced bone remodeling (Boe et al. Citation2011b). However, there is not much knowledge on the influence of the surgical approach to the hip joint and how this may affect bone remodeling around a femoral stem.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry studies in patients receiving a total hip arthroplasty (THA) for osteoarthritis showed increased bone resorption in the direct lateral approach compared with the anterolateral approach (Perka et al. Citation2005, Merle et al. Citation2012). This may be due to compromised vascularization or possibly the alteration of the hip abductors and the musculoskeletal load to the proximal femur. Patients with femoral neck fracture are especially prone to periprosthetic fractures (Langslet et al. Citation2014, Skoldenberg et al. Citation2014) and bone remodeling and approach has not been studied in this patient group.

In this trial we hypothesized that the anterolateral (modified Watson-Jones) approach would give less bone loss around the femoral stem than the direct lateral (Hardinge) approach in patients with FNF.

Patients and methods

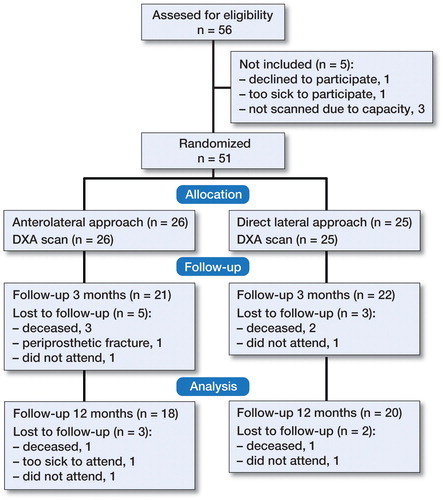

This subgroup analysis is part of a larger ongoing level I single-center randomized trial carried out at Soerlandet Hospital Kristiansand, Norway. The planning and the design of the subgroup analyses were pre-specified in the study protocol of the main randomized trial. Statistical tests were performed on a hypothesis pre-specified in the study protocol and sample size calculation was performed prior to acquisition of data. The endpoint was change in BMD as measured by DXA at 3 and 12 months. Patients between 70 and 90 years of age with displaced femoral neck fractures, intact cognitive function and the ability to walk with or without a walking aid prior to falling were asked for their agreement to be enrolled and participation occurred after informed consent. Exclusion criteria were dementia, fractures in pathologic bone or patients not belonging to the hospital community. Those who displayed sepsis or local infection and not eligible to be treated with a hemiarthroplasty were not included. 51 patients were enrolled in the DXA sub-study and underwent DXA between February 2014 and March 2016 (). The first 56 patients included in the main study (n = 120) were assessed for eligibility. 5 patients were not included.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of included patients according to allocated surgical approach (figures are numbers unless stated otherwise)

The physician on duty evaluated whether the inclusion criteria were fulfilled and gave both verbal and written information about the trial. Randomization for surgery with either a direct lateral approach or an anterolateral approach was done by the same physician drawing a sealed envelope. Blinded study personnel recorded and monitored primary and secondary outcome measures.

We used the Corail stem (DePuy Orthopaedics Inc., Warsaw, IN, USA) intended for uncemented fixation, collared with standard offset and 135° neck angle. This is a titanium alloy straight stem with a grit-blasted surface and 155 µm of hydroxyapatite coating. The implant has a trapezoidal-like proximal cross section to provide rotational stability and self-locking, whereas the distal part is tapered. The SELF-CENTERING Bi-Polar Head was combined with an ARTICULEZE 28 mm femoral head, both from Depuy Synthes (West Chester, PA, USA) (). Preoperative planning was performed using Sectra Medical Systems, Orthopaedic Package v5.5 (Sectra AB, Linköping, Sweden).

Patients were operated within 48 hours after sustaining their fracture. Operation was performed by 3 consultants in orthopedic hip surgery familiar with both approaches. The procedure was carried out under spinal anesthesia and all received the same standard analgesic protocol. Preoperatively 2 grams of cefalotin was given intravenously and a further 3 doses of 2 grams given over the next 24 hours. Low-dose heparin 40 mg (enoxaparin) was prescribed for 10 days.

The standard lateral decubitus position was selected for the direct lateral approach and the supine position for the anterolateral approach. For both procedures the femoral neck was resected and the femur reamed according to the preoperative planning or until rotational stability was achieved. The gluteal muscles were reinserted through osteosutures. There was no use of drainage and immediate full weight bearing was encouraged. Patients were examined with DXA within 3 days after surgery. Femoral BMD was measured on a GE Lunar Prodigy (GE Medical Systems, Madison, WI, USA).

BMD was measured postoperatively, at 3 and 12 months. The findings obtained at the postoperative scan were defined as baseline data.

The DXA measurement was performed by the technicians at the osteoporosis clinic, who were blinded to the allocated treatment.

Patients were positioned in the supine position with a triangle between the feet to obtain a standard rotation of the hip. Both hips were included. Readings started in the area about 2 centimeters proximal to the greater trochanter and distally to just below the femoral stem. The baseline scan was performed twice, and the patient moved between each scan. This was to estimate the precision expressed as coefficient of variation for the measurement procedure (Wilkinson et al. Citation2001). Changes in BMD related to the Gruen zones were then recorded and expressed as change in percentage using software from Orthopedic Hip for GE Lunar Prodigy (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA).

Statistics

Power calculations were based on previous studies on bone remodeling around the femoral stem (Boe et al. Citation2011b, Merle et al. Citation2012, Salemyr et al. Citation2015). We estimated a clinically important difference in BMD would be 10% (SD 10) between groups. To obtain a statistical power of 80% at the 0.05 level of significance 34 patients would be required, i.e. 17 in each treatment arm. We planned to include 50 patients to allow for loss to follow-up.

We used the double scans at baseline with repositioning between each scan to calculate the in-vivo precision error for the BMD procedures. Based upon the difference between these 2 scans the coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated for each ROI according to the formula: CV% = 100 X[(δ/√2)/µ], where δ represents the standard deviation of the differences between the paired BMD measurements, and µ is the overall mean of all the measurements for that ROI.

The change in BMD was calculated and the results expressed as percentage change with 95% confidence interval (CI) of postoperative values at 3 and 12 months for all regions of interest (ROI). The mean bone mineral density (g/cm2) postoperatively served as baseline. Bone density data were analyzed for normal distribution using histograms, Q-Q plots and the Shapiro–Wilk test. The groups were compared with Student’s t-test. A paired samples t-test was conducted to compare changes in BMD from baseline to follow-ups. The results were also reassessed with linear mixed models for repeated measurements, but we reported only results from t-tests since that statistical approach was pre-specified in the protocol. We did not perform adjustments for multiple tests.

A p-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS Statistics 21 for Windows (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

Ethics, registration, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

The trial was approved by the regional ethics committee (2013/1853/REK) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT02028468). The trial was reported based on the guidelines of the CONSORT Statement (Schulz et al. Citation2010) and designed in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. All patients provided informed consent. The trial protocol was awarded an independent research grant of 25,000 Norwegian kroner from Smith and Nephew at the Norwegian Orthopedic meeting in 2013. Smith and Nephew took no part in organizing the study, in analyzing, or in writing the manuscript. The trial was funded by Helse Sør-Øst RHF and the Norwegian authorities through a PhD grant. No competing interests were declared.

Results

Patient characteristics

51 patients were included in this sub-study. 26 were randomized to the anterolateral group and 25 to the direct lateral group. Mean age was 83 (70–90) years and 33 were female (). They were mainly ASA II (29%) and ASA III (58%) patients with a mean BMI of 23 (15–33). Time from admission to surgery and duration of surgery were similar in the 2 groups. The classification of proximal femoral types according to Dorr et al. (Citation1993) and the stem size inserted were similar in the 2 groups. The groups were comparable regarding stem alignment (Aldinger et al. Citation2009). Timed Up and Go test (TUG) performed at all 3 points of follow-up was similar between groups. A review of eligible medical records confirmed that the 2 groups were comparable regarding the prescription of bisphosphonates. At inclusion 4 patients were on osteoporosis medication. 7 patients died during the follow-up period and 5 patients did not attend the scheduled follow-up because of their health status. 1 patient with a periprosthetic fracture after a fall on the second postoperative day was excluded ().

BMD measurements

The precision of the DXA measurements differed from 1.2% in Gruen zone 4 to 5.5% in Gruen zone 6 (). The 2 groups had similar BMD at the immediate postoperative measurement, both in the affected hip and in the contralateral hip. We found a continuous reduction in total periprosthetic BMD from baseline to 12 months. At 3 months there was a mean reduction in total periprosthetic BMD (4.2%, CI 2.4–6.1; p < 0.001). Likewise there was a mean reduction in total periprosthetic bone at 12 months (5.8%, CI 3.3–8.3; p < 0.001).

Table 2. Precision of DXA measurements. Coefficients of variation (CV%)

At 3 months there was a mean reduction in total periprosthetic bone of 1.6% in the anterolateral group compared with 6.5% in the lateral group. The corresponding numbers at 12 months were 3.3% reduction in the anterolateral group versus 8.1% in the lateral group. The mean change in total BMD from baseline to follow-ups differed between groups in favor of the anterolateral group (at 3 months 4.8%, CI 1.6–8.1, p = 0.04; and at 12 months 4.8%, CI 0.0–9.6, p = 0.05). We found a continuous decrease in bone mineral around the femoral stem in the proximal Gruen zones for up to 12 months after surgery. In the direct lateral approach we found an early loss of BMD in all Gruen zones at 3 and 12 months. It was most pronounced between the baseline and the 3 months examination. In the anterolateral group the mean BMD in zone 1 and 2 increased between the baseline scan and the 3-month examination, with a loss of bone mineral in the remaining regions except zone 6, where BMD remained unchanged (). Statistical analysis confirmed a significant reduction of BMD in Gruen zones 1, 2, 6, and 7 (p < 0.05) in the lateral group compared with the anterolateral group: Gruen zone 1 (–5.0% vs. 2.7%), zone 2 (–4.3% vs. 4.1%), zone 6 (–6.5% vs. 0.0%), and zone 7 (–11% vs. –2.4%, all p < 0.05). There was a mean difference in Gruen zone 1 (7.7%, CI 0.0–15; p = 0.04), Gruen zone 2 (8.4%, CI 1.1–16; p = 0.02), Gruen zone 6 (6.5%, CI 0.2–13; p = 0.04), and Gruen zone 7 (8.8%, CI 0.1–18; p = 0.04), all in favor of the anterolateral group. The results were confirmed by a linear mixed model for repeated measurements analysis. At 12 months the tendency remained although now only significant in zone 6 (p < 0.05).

Table 3. Periprosthetic changes in bone mineral density (BMD) around the hydroxyapatite-coated Corail stem measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA)

Discussion

We are not aware of any randomized trials examining the influence of the surgical approach on bone mineral changes in patients with femoral neck fractures. In this subgroup analysis of a randomized clinical trial reduction in BMD was higher in all Gruen zones in the direct lateral approach compared with the anterolateral approach after 3 months, which was statistically significant in the most proximal zones.

Changes in BMD around the femoral implant are a result of surgery-induced bone remodeling (Yamaguchi et al. Citation2000, Digas et al. Citation2009, Boe et al. Citation2011b, Tice et al. Citation2015). The complexity of this process is not fully understood as the etiology is thought to be multifactorial. Different implant designs, coatings (Flatoy et al. Citation2016) and stem sizes seem to influence periprosthetic bone remodeling (Karrholm et al. Citation2002, Nishino et al. Citation2013, Inaba et al. Citation2016). In our study, stem size was similar between groups and a single design only was used to minimize confounding effects. Activity may be a contributing factor (Hayashi et al. Citation2012) as well as loading of the proximal femur and local vascular status after the surgical trauma. The surgical technique itself is prone to influence BMD around the stem. Compaction of bone or excessive rasping prior to insertion of the stem is such a factor. An increase in bone density was measured by Kold et al. (Citation2005) in an animal model after compaction around a hydroxyapatite-coated implant and Boe et al. (Citation2011a) found increased BMD during the first 14 days after insertion of the same stem as we used in this study.

The blood supply to the greater trochanter was studied in a perfusion experiment on fresh cadavers (Churchill et al. Citation1992). Branches from the gluteal vessels enter the trochanter at the insertion site of the M. gluteus medius, which is dissected when performing the direct lateral approach. Decreased blood supply may have influenced bone loss in the present study. Naito et al. (Citation1996) reported a substantial decrease of blood flow rate to the greater trochanter in adult rabbits after dissecting the gluteus medius and minimus of its bony insertion site. These findings may be a plausible explanation for the altered bone remodeling in the lateral group as the abductor muscles were not dissected in the anterolateral group.

Previous studies on the significance of the surgical approach on bone loss around the femoral stem have been done in total hip replacement (THR) for osteoarthritis. In a non-randomized study, Merle et al. (Citation2012) found increased bone loss for the direct lateral approach in some Gruen zones compared with the anterolateral approach. These were planned total hip arthroplasties for osteoarthritis and patients were scanned with DXA in a 12-month follow-up with a partial weight-bearing protocol in the direct lateral group. Perka et al. (Citation2005) also found a statistically significant femoral bone loss in the direct lateral approach versus the anterolateral at 5.5-year follow-up. Taylor et al. (Citation2012) did not find a statistically significant reduction in BMD for the proximal Gruen zones in the direct lateral approach in THR stating that only the combination of age and sex were predictors of postoperative remodeling rate.

Different weight-bearing regimes in the rehabilitation period may influence the pattern of bone remodeling around the implant although this question is not fully resolved. Partial weight bearing may contribute to bone loss (Boden et al. Citation2004), thus leaving unanswered the question of to what extent the surgical approach has an impact on bone mineral changes. In our study both groups were allowed full weight bearing. The patterns of bone formation may be guided by the vascularization of the greater trochanter and different loads on the proximal femur with functional load-bearing favoring bone remodeling (Rubin and Lanyon Citation1984). Thus, it seems reasonable that the surgical approach influences the process of periprosthetic bone adaptation, possibly contributing to the reported increased fracture risk around uncemented stems. Numbers from the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association (NARA) show that nearly all of the periprosthetic fractures with uncemented stems occurred within the first 6 months after surgery (Gjertsen et al. Citation2012, Langslet et al. Citation2014, Thien et al. Citation2014, Inngul et al. Citation2015).

As literature on this issue is sparse we can only compare our results with studies on THR in osteoarthritis patients. Statistical power was based on sample size calculation from these studies and may not reflect the true nature of the problem. The limitations include some loss to follow-up and possibly the short period of observation.

Furthermore we allowed immediate full weight bearing in both groups including the TUG test but did not quantify the amount of mobilization possibly affecting proximal bone resorption. The analyses of the subgroup had a confirmatory statistical strategy with a single variable and a pre-specified hypothesis. We report on confidence intervals to emphasize clinical significance. No interim analysis was performed.

In summary, at 3 months we found a statistically significant reduction of bone mineral in the proximal Gruen zones in the direct lateral approach compared with the anterolateral approach. We did not perform adjustments for multiple tests, possibly leading to inflation of false-positive findings. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution.

TU wrote the protocol, planned and conducted the study, performed surgery and statistical analysis, and wrote the paper. LN supervised in writing the protocol, data collection, and helped with manuscript preparation. GH supervised in writing the protocol, analysis of DXA measurements, and helped with manuscript preparation. SS supervised in writing the protocol and helped with manuscript preparation. SU and ØB helped in planning the study, performing surgery, and manuscript preparation. AP helped in the statistical data analysis.

The authors would like to express their gratitude and thanks to Isabel Priscilla Nunez for acquisition of data, database management, and organizing the follow-ups at the outpatient clinic. They thank the staff at the Osteoporosis Clinic, Soerlandet Hospital, for performing the DXA examinations. The authors would like to thank physiotherapists Linda Hansen and Arild Ege.

Acta thanks Anders Enocson and other anonymous reviewers for help with peer review of this study.

- Aldinger P R, Jung A W, Breusch S J, Ewerbeck V, Parsch D. Survival of the cementless Spotorno stem in the second decade. Clin Orth Relat Res 2009; 467 (9): 2297–304.

- Boden H, Adolphson P. No adverse effects of early weight bearing after uncemented total hip arthroplasty: A randomized study of 20 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 2004; 75 (1): 21–9.

- Boe B, Heier T, Nordsletten L. Measurement of early bone loss around an uncemented femoral stem. Acta Orthop 2011a; 82 (3): 321–4.

- Boe B G, Rohrl S M, Heier T, Snorrason F, Nordsletten L. A prospective randomized study comparing electrochemically deposited hydroxyapatite and plasma-sprayed hydroxyapatite on titanium stems. Acta Orthop 2011b; 82 (1): 13–9.

- Churchill M A, Brookes M, Spencer J D. The blood supply of the greater trochanter. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1992; 74 (2): 272–4.

- Digas G, Karrholm J. Five-year DEXA study of 88 hips with cemented femoral stem. Int Orthop 2009; 33 (6): 1495–500.

- Dorr L D, Faugere M C, Mackel A M, Gruen T A, Bognar B, Malluche H H. Structural and cellular assessment of bone quality of proximal femur. Bone 1993; 14 (3): 231–42.

- Flatoy B, Rohrl S M, Boe B, Nordsletten L. No medium-term advantage of electrochemical deposition of hydroxyapatite in cementless femoral stems: 5-year RSA and DXA results from a randomized controlled trial. Acta Orthop 2016; 87 (1): 42–7.

- Gjertsen J E, Lie S A, Vinje T, Engesaeter L B, Hallan G, Matre K, Furnes O. More re-operations after uncemented than cemented hemiarthroplasty used in the treatment of displaced fractures of the femoral neck: An observational study of 11,116 hemiarthroplasties from a national register. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012; 94 (8): 1113–19.

- Grant P, Aamodt A, Falch J A, Nordsletten L. Differences in stability and bone remodeling between a customized uncemented hydroxyapatite coated and a standard cemented femoral stem: A randomized study with use of radiostereometry and bone densitometry. J Orthop Res 2005; 23 (6): 1280–5.

- Hayashi S, Nishiyama T, Fujishiro T, Kanzaki N, Hashimoto S, Kurosaka M. Periprosthetic bone mineral density with a cementless triple tapered stem is dependent on daily activity. Int Orthop 2012; 36 (6): 1137–42.

- Inaba Y, Kobayashi N, Oba M, Ike H, Kubota S, Saito T. Difference in postoperative periprosthetic bone mineral density changes between 3 major designs of uncemented stems: A 3-year follow-up study. J Arthroplasty 2016; 31(8): 1836–41.

- Inngul C, Blomfeldt R, Ponzer S, Enocson A. Cemented versus uncemented arthroplasty in patients with a displaced fracture of the femoral neck: A randomised controlled trial. Bone Joint J 2015; 97-B (11): 1475–80.

- Karrholm J, Anderberg C, Snorrason F, Thanner J, Langeland N, Malchau H, Herberts P. Evaluation of a femoral stem with reduced stiffness: A randomized study with use of radiostereometry and bone densitometry. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002; 84-A (9): 1651–8.

- Kold S, Rahbek O, Zippor B, Bechtold J E, Soballe K. Bone compaction enhances fixation of hydroxyapatite-coated implants in a canine gap model. J Biomed Mat Res Part B, Applied Biomaterials 2005; 75 (1): 49–55.

- Langslet E, Frihagen F, Opland V, Madsen J E, Nordsletten L, Figved W. Cemented versus uncemented hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures: 5-year followup of a randomized trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472 (4): 1291–9.

- Lindahl H. Epidemiology of periprosthetic femur fracture around a total hip arthroplasty. Injury 2007; 38 (6): 651–4.

- Malchau H, Herberts P, Ahnfelt L. Prognosis of total hip replacement in Sweden: Follow-up of 92,675 operations performed 1978–1990. Acta Orthop Scand 1993; 64 (5): 497–506.

- Merle C, Sommer J, Streit M R, Waldstein W, Bruckner T, Parsch D, Aldinger P R, Gotterbarm T. Influence of surgical approach on postoperative femoral bone remodelling after cementless total hip arthroplasty. Hip Int 2012; 22 (5): 545–54.

- Naito M, Ogata K, Emoto G. The blood supply to the greater trochanter. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996; (323): 294–7.

- Nishino T, Mishima H, Kawamura H, Shimizu Y, Miyakawa S, Ochiai N. Follow-up results of 10-12 years after total hip arthroplasty using cementless tapered stem: Frequency of severe stress shielding with synergy stem in Japanese patients. J Arthroplasty 2013; 28 (10): 1736–40.

- Perka C, Heller M, Wilke K, Taylor W R, Haas N P, Zippel H, Duda G N. Surgical approach influences periprosthetic femoral bone density. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005; (432): 153–9.

- Rubin C T, Lanyon L E. Regulation of bone formation by applied dynamic loads. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1984; 66 (3): 397–402.

- Salemyr M, Muren O, Ahl T, Boden H, Eisler T, Stark A, Skoldenberg O. Lower periprosthetic bone loss and good fixation of an ultra-short stem compared to a conventional stem in uncemented total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2015; 86(6): 659–66.

- Schulz K F, Altman D G, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2010; 1 (2): 100–7.

- Skoldenberg O G, Sjoo H, Kelly-Pettersson P, Boden H, Eisler T, Stark A, Muren O. Good stability but high periprosthetic bone mineral loss and late-occurring periprosthetic fractures with use of uncemented tapered femoral stems in patients with a femoral neck fracture. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (4): 396–402.

- Taylor W R, Szwedowski T D, Heller M O, Perka C, Matziolis G, Muller M, Janshen L, Duda G N. The difference between stretching and splitting muscle trauma during THA seems not to play a dominant role in influencing periprosthetic BMD changes. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2012; 27 (8): 813–18.

- Thien T M, Chatziagorou G, Garellick G, Furnes O, Havelin L I, Makela K, Overgaard S, Pedersen A, Eskelinen A, Pulkkinen P, Karrholm J. Periprosthetic femoral fracture within two years after total hip replacement: Analysis of 437,629 operations in the Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association database. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96 (19): e167.

- Tice A, Kim P, Dinh L, Ryu J J, Beaule P E. A randomised controlled trial of cemented and cementless femoral components for metal-on-metal hip resurfacing: A bone mineral density study. Bone Joint J 2015; 97-B (12): 1608–14.

- Wilkinson J M, Peel N F, Elson R A, Stockley I, Eastell R. Measuring bone mineral density of the pelvis and proximal femur after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001; 83 (2): 283–8.

- Yamaguchi K, Masuhara K, Ohzono K, Sugano N, Nishii T, Ochi T. Evaluation of periprosthetic bone-remodeling after cementless total hip arthroplasty: The influence of the extent of porous coating. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000; 82-A (10): 1426–31.