Abstract

Background and purpose — Immediate postoperative pain management offered in knee arthroplasty is suboptimal in up to one-third of patients resulting in high opiate consumption and delayed discharge. In this meta-analysis we investigate the analgesic effect and safety of perioperative adjuvant corticosteroids in knee arthroplasty.

Methods — Databases Medline, Embase, and Central were searched for randomized studies comparing the analgesic effect of adjuvant perioperative corticosteroids in knee arthroplasty. Our primary outcome was pain score at 24 hours postoperatively. Secondary outcomes included pain at 12, 48, and 72 hours, opiate consumption, postoperative nausea and vomiting, infection, and discharge time. Systemic (intravenous) and local (intra-articular) corticosteroids were analyzed separately.

Results — 14 randomized controlled trials (1,396 knees) were included. Mean corticosteroid dosages were predominantly 50–75mg oral prednisolone equivalents for both systemic and local routes. Systemic corticosteroids demonstrated statistically significant and clinically modest reductions in pain at 12 hours by –1.1 points (95%CI –2.2 to 0.02), 24 hours by –1.3 points (CI –2.3 to –0.26) and 48 hours by –0.4 points (CI –0.67 to –0.04). Local corticosteroids did not reduce pain. Opiate consumption, postoperative nausea and vomiting, infection, or time till discharge were similar between groups.

Interpretation — Corticosteroids modestly reduce pain postoperatively at 12 and 24 hours when used systemically without any increase in associated risks for dosages between 50 and 75 mg oral prednisolone equivalents.

Pain is one of the main reasons for hospital stay after knee arthroplasty; finding the best pain control regime postoperatively is therefore important (Husted et al. Citation2011, James Lind Alliance Citation2017).

Traditionally pain control following surgery heavily relied on the use of systemic opiates, which are associated with multiple side effects including muscle weakness, light sedation, and hypotensive effects, directly impacting postoperative rehabilitation (Barletta Citation2012, Oderda Citation2012). Optimization of perioperative opiate analgesia has been shown to reduce length of stay and often improves patient satisfaction as well as reducing the incidence of chronic pain and functional outcomes after surgery (Halawi et al. Citation2015, Meissner et al. Citation2015).

At present, there is no consensus regarding the use of corticosteroids in the perioperative period following knee arthroplasty. It is not known whether they should be used as part of an enhanced recovery program, and if so, whether to administer them systemically or locally. The objective of this systematic review is to assess the effect of adjunctive perioperative corticosteroids on postoperative pain in adult patients undergoing knee arthroplasty.

Methods

The prospectively registered protocol (PROPSERO - CRD42016049336) has been published (Mohammad et al. Citation2017). The work follows the PRISMA guidelines.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for studies were: (1) randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the effect of adjunctive perioperative corticosteroid on analgesic regimens in knee surgery (administered immediately before surgery or intraoperatively), (2) patients 18 years and over, (3) systemic (intravenous) or local (intra-articular) corticosteroid administration, and (4) anesthetic regimens must be the same for treatment and control groups. Exclusion criteria were: (1) corticosteroid administration through spinal/perineural/epidural space due to procedure-related confounding factors on pain, and (2) articles not available in the English language.

Search strategy and study inclusion

An expert information analyst searched electronic databases (Medline [Ovid], Embase [Ovid] and Central [Cochrane Library]) from their inception to November 10, 2016. An updated search in September 2017 found no new RCTs had been published with pain as a primary outcome, making our search up to date. The full search strategies are available (see Supplementary data; Appendix: Search E1–3). Studies were assessed independently for inclusion by two authors (HRM and TWH).

Outcome measures assessed

Primary outcome was resting mean pain score at 24 hours following surgery (continuous variable). The secondary continuous outcomes were mean pain score difference at 12, 48, and 72 hours, mean opiate consumption (intravenous morphine equivalents) 24 hours postoperatively, and time till discharge. Secondary dichotomous outcomes were the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) during the first 24 hours postoperatively and incidence of reported infections.

The meaningful interpretation of the different corticosteroids and their dosages used in different studies was ensured by using well-established conversion charts (Hu Citation2010) to convert them into oral prednisolone equivalents.

We contacted included studies’ authors when data were missing or incomplete. If authors were unavailable we estimated data where possible, using the recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins et al. Citation2011).

2 authors (HRM, TWH) independently assessed the risk of bias of included studies using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (Schünemann et al. Citation2011). The risk of publication bias could not be explored as there were less than 10 studies per outcome available.

Data synthesis and analysis

For continuous data, including data reported in scales, we used the inverse variance method to report the pooled mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Where data were reported in different scales, we used the standardized mean difference (SMD) and CI in the analysis. All statistically significant pooled SMDs were back-transformed into the scale of interest (VAS 10 mm scale/intravenous morphine equivalents in our study). This was calculated by multiplying the pooled SMD by the largest study’s control group standard deviation (SD) of the said scale. We did not pool medians and interquartile range given this type of data is usually skewed and hence inappropriate for meta-analysis. For dichotomous outcomes we used the Mantel–Haenszel method, reporting the pooled risk ratio (RR) and CI. Significance was set at p < 0.05 (Oxman et al. Citation2004).

We expected high heterogeneity as a result of the different pain scales and anesthetic regimens used by researchers. Hence we employed the random effects model in meta-analysis to allow for heterogeneity. We used the I2 index to quantify heterogeneity, and we did not report the pooled result if it was substantial (I2 > 85%) and there was inconsistent direction of effect. The unit of analysis for pain and infection was the knee. For the outcomes postoperative nausea and vomiting, time till discharge, and opiate consumption the unit of analysis was the patient.

We conducted analysis on the route of corticosteroid administration separately: systemic (intravenous) and local (intraarticular). We carried out sensitivity analysis by temporarily removing studies at high risk of bias for blinding and allocation concealment domains. Meta-analyses were conducted using Review Manager 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre; The Cochrane Collaboration).

Funding and potential conflicts of interest

No specific funding was received for this research. Some of the authors have received or will receive benefits for personal or professional use from a commercial party (Zimmer Biomet) not related to this article.

Results

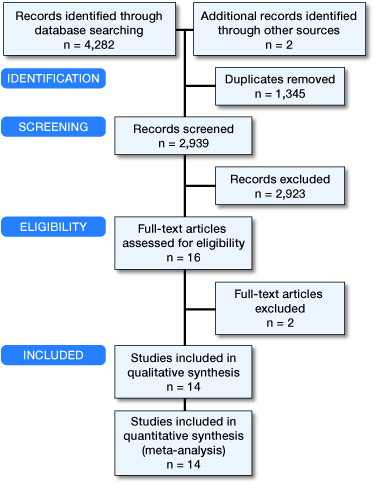

From 4,282 titles identified, 14 studies (n = 1,396 knees) met the inclusion criteria (, Table 1, see Supplementary data). The vast majority of corticosteroids in oral prednisolone equivalents ranged between 50 mg and 75 mg for both systemic corticosteroids and local corticosteroids. This did not allow for dosage-related effects to be investigated given the tight dosage range. All corticosteroids were administered just before or during surgery.

Sensitivity analyses did not raise any issues on the robustness of the pooled results and hence have not been reported separately. Studies that did not report our outcomes of interest in a format suitable for meta-analysis are summarized in Table 2 (see Supplementary data). Formats not suitable included studies reporting medians with interquartile ranges, given that this suggests the data are non-normally distributed making conversion to means and standard deviations controversial (Higgins and Green Citation2011). Furthermore, papers only reporting means without standard deviations, standard errors, or confidence intervals could not be included given that one of these is required with the mean for meta-analysis. All studies reported in Table 2 (see Supplementary data) fall into the above categories.

Most studies scored low or unclear risk of bias in all domains; Figure 2 (see Supplementary data) shows graphically a summary of the risk of bias assessments. Only 2 studies demonstrated evidence of high risk of bias in any domain. Christensen et al. (Citation2009) reported broken blinding for 4 patients in the steroid group and hence this study was excluded from reported results involving pain outcomes, given their subjective nature (see Supplementary data, Appendix: Figure E1 for analysis including Christensen et al. (Citation2009)). Chia et al. (Citation2013) showed evidence of reporting bias as they describe in the methods section that daily pain measurements were taken, but only reported pain at weekly intervals in the results. Wherever meta-analysis is reported not possible, this is because less than 2 studies report the outcome.

Pain at 24 hours

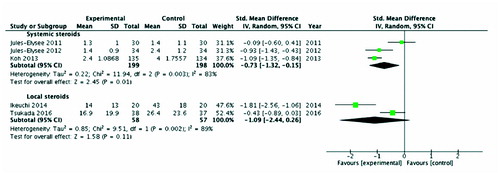

The systemic corticosteroid group (n = 397, 3 studies: Jules-Elysee et al. Citation2011, Citation2012, Koh et al. Citation2013) had significantly lower pain compared with the control group SMD –0.73 (CI –1.3, –0.15; I2 = 83%; p = 0.01) equating to –1.3 points on VAS 10 mm scale (CI –2.3, –0.26). For local corticosteroids (n = 115, 2 studies: Koh et al. Citation2013, Ikeuchi et al. Citation2014) there were no statistical significant differences in pain between them and their controls ().

Figure 3. Pain scores at 24 hours postoperatively. Note: First-named author only cited for each study

Systemic corticosteroid studies which could not be included in meta-analysis (n = 138, 2 studies: Lunn et al. Citation2011, Kim et al. Citation2015) both demonstrated a reduction in pain scores at 24 hours in steroid groups. Local corticosteroid studies (n = 172, 2 studies: Seah et al. Citation2011, Yue et al. Citation2013) which could not be included in meta-analysis also demonstrated a reduction in pain scores at 24 hours (Table 2, see Supplementary data).

Pain at 12 hours

There was a statistically significant reduction in pain for systemic corticosteroids (n = 128, 2 studies: Jules-Elysee et al. Citation2011, Citation2012) SMD –0.54 (CI –1.08, 0.01; I2 = 58%; p = 0.05) equating to –1.1 VAS 10mm points (CI –2.16, 0.02) compared with control. It was not possible to meta-analyze local corticosteroids (see Supplementary data; Appendix: Figure E2).

One systemic corticosteroid study that could not be included in meta-analysis (n = 90, 1 study (Kim et al. Citation2015) demonstrated reduced pain in corticosteroid groups. 3 local corticosteroid studies (n = 247: Seah et al. Citation2011, Yue et al. Citation2013, Tsukada et al. Citation2016) of which 2 studies reported lower pain in the corticosteroid group (Table 2, see Supplementary data).

Pain at 48 hours

Systemic corticosteroids demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in pain (n = 329, 2 studies: Jules-Elysee et al. Citation2011, Koh et al. Citation2013) –0.24 SMD (CI –0.46, –0.03’ I2 = 0%; p = 0.03) equating to –0.4 VAS 10 mm points (CI –0.67, –0.04) (See supplementary data, Appendix: Figure E3). Meta-analysis was not possible for local steroids.

Systemic corticosteroid studies that could not be included in meta-analysis (n = 138, 2 studies: Lunn et al. Citation2011, Kim et al. Citation2015) demonstrated reduced pain in corticosteroid groups. Local corticosteroid studies could not be included in meta-analysis (n = 147, 2 studies: Yue et al. Citation2013, Tsukada et al. Citation2016), 1 of which reported lower pain in the corticosteroid group (Table 2, see Supplementary data).

Pain at 72 hours

Meta-analysis was possible only for local corticosteroids (n = 115, 2 studies: Ikeuchi et al. Citation2014, Tsukada et al. Citation2016), showing no statistically significant difference in pain (see Supplementary data; Appendix: Figure E4). Koh et al. Citation2013 (n = 269) report lower pain scores in the systemic steroid group.

Postoperative nausea and vomiting 24 hours postoperatively

Both systemic corticosteroids (n = 112, 3 studies: Lunn et al. Citation2011, Jules-Elysee et al. Citation2011, Citation2012) and local corticosteroids (n = 160, 2 studies: Kim et al. Citation2015, Tsukada et al. Citation2016) showed no statistically significant differences in postoperative nausea and vomiting between them and their controls (see Supplementary data; Figure 4).

One systemic corticosteroid paper (Koh et al. Citation2013) could not be included in meta-analysis (n = 269) but reported fewer cases of postoperative nausea and vomiting in the corticosteroid group (Table 2, see Supplementary data). No gastrointestinal complications were reported with corticosteroid use in any paper.

Infection

Systemic corticosteroid studies (n = 206, 3 studies: Jules-Elysee et al. Citation2011, Citation2012; Lunn et al. Citation2011) reported no infections in either intervention group. Koh et al. (Citation2013) (n = 269) using systemic corticosteroids reported 1 infection in each group. In local corticosteroids (n = 325, 4 studies: Pang et al. Citation2008, Christensen et al. Citation2009, Seah et al. Citation2011, Chia et al. Citation2013) there was no significant difference between groups (see Supplementary data; Figure 5). 5 studies (Ng et al. Citation2011, Chia et al. Citation2013, Ikeuchi et al. Citation2014, Kim et al. Citation2015, Tsukada et al. Citation2016) (n = 343) using local corticosteroids reported no infections in the control or corticosteroid groups. There were no other reported adverse effects associated with corticosteroid use in all shortlisted studies. gives details of all infections reported.

Table 3. Details of infection cases reported from meta-analysis

Opiate consumption 24 hours postoperatively

No systemic corticosteroid studies reported this outcome in a format suitable for meta-analysis. In local corticosteroids (n = 251, 3 studies: Pang et al. Citation2008, Christensen et al Citation2009, Kim et al. Citation2015) there were no significant differences between the corticosteroid and control groups (see Supplementary data; Appendix: Figure E5).

One systemic corticosteroid paper that could not be included in meta-analysis (n = 48, 1 study: Lunn et al. Citation2011) reported lower opiate consumption in the corticosteroid group. Local corticosteroid papers that could not be included in meta-analysis (n = 172, 2 studies: Seah et al. Citation2011, Yue et al. Citation2013) reported lower opiate consumption in corticosteroid groups (Table 2, see Supplementary data).

Mean time till discharge

No statistically significant differences in time till discharge were noted between systemic corticosteroid (n = 64, 2 studies: Jules-Elysee et al. Citation2011, Citation2012) and control groups (see Supplementary data; Appendix: Figure E6). Local corticosteroid meta-analysis was not possible.

There was 1 systemic corticosteroid paper (Lunn et al. Citation2011) that could not be included in meta-analysis (n = 48), which reported faster discharge times in the corticosteroid group by one day. There were 2 local corticosteroid studies (Christensen et al. Citation2009, Seah et al. Citation2011) that could not be included in meta-analysis (n = 175) that also reported faster discharge in the corticosteroid group by approximately 1 day.

Other unwanted side effects

There were no cases of avascular necrosis reported in the included studies although we were severely limited by the short follow-up periods and number of patients. Only 2 studies reported the blood glucose levels of their patients. Jules-Elysee et al. (Citation2011) reported higher immediate postoperative mean glucose levels in the steroid group (133mg/dL) versus the control group (102mg/dL). Jules Elysee et al. (2012) reported higher immediate postoperative mean glucose levels in the steroid group at 128mg/dL compared with 101mg/dL in the control group.

Discussion

To our knowledge no previous meta-analysis has explored the adjunctive effect of both systemic and local steroids in knee arthroplasty while allowing for heterogeneity.

The minimum clinically significant difference in resting pain scores reported is 0.9 points on the VAS 10 mm scale (Machado et al. Citation2015). Our meta-analysis found that systemic corticosteroids demonstrated reductions in resting pain at 12 (1.1 points) and at 24 hours (1.3 points). Local corticosteroids did not provide any analgesic effect in knee arthroplasty although this may be due to our lower number in the meta-analysis.

We found similar rates of postoperative nausea and vomiting, infection, time till discharge, and opiate consumption between the two groups. However, all the studies meta-analyzed for opiate consumption were local steroids.

A systematic review by Tran and Schwarzkopf (Citation2015) did not find any evidence of an analgesic effect of local corticosteroid injections in knee arthroplasty. Additionally, no differences between the steroid and control groups were reported for infection and opiate consumption; this is in concordance with our work. 2 reviews observing the effects of systemic corticosteroid administration explored surgery as a whole rather than subgrouping analysis on specific procedures or even surgical specialties (De Oliveira et al. Citation2011, Waldron et al. Citation2012). Analyzing all surgical procedures as a whole incurs considerable clinical heterogeneity given that the surgeries vary drastically. Despite this limitation, De Oliveira et al. (Citation2011) in their systematic review of systemic corticosteroids (intravenous dexamethasone) demonstrated a reduction in pain at 24 hours and no differences in infection between the corticosteroid and no-corticosteroid groups. Waldron et al. (Citation2012) in their systematic review of systemic corticosteroids (intravenous dexamethasone) in all surgical specialties found substantial reductions in pain at 24 hours and no increase in infection risk. Although the results of pain at 24 hours, infection risk, and opiate consumption are in agreement with published findings there are some differences. All the above reviews suggest faster discharge times and reduced postoperative nausea and vomiting in the corticosteroid group, which we did not observe in our meta-analysis. This may be due to these studies using heterogeneous types of surgery and not using uniform time points in the analysis or due to studies being excluded from meta-analysis that report a reduction.

Romundstad et al. (Citation2004) conducted a double-blind RCT on intravenous corticosteroids (oral prednisolone equivalents of 156 mg) 1 day after orthopedic surgery and found analgesic effects at 24 hours, and lower opiate consumption at 72 hours. This could perhaps suggest that it takes longer for the opiate reduction effect to become evident or that the doses of steroids in our meta-analysis were not high enough to elicit this effect.

There are some limitations to our meta-analysis. There were not many studies using different doses of corticosteroids to allow meaningful evaluation of any dosage effects. Furthermore, there was substantial heterogeneity given the different scales used, anesthetic regimens, and patient demographic differences. The anesthetic regimens were, however, matched within each RCT. Although there was high heterogeneity in some of our analysis, all studies’ effect measurements were consistent in the same effect direction, varying in the strength of the effect. Furthermore, several studies did not report all of our outcomes of interest, clearly indicating there is no consensus in the literature on what the important outcomes are and the measurement timing when exploring the effects of corticosteroids in surgery. There was a lack of reporting of patients’ blood glucose despite elevated blood glucose being a well-recognized side effect of corticosteroids. Another important limitation is that studies used different corticosteroids. However, 12 of the 14 papers used short- to intermediate-acting corticosteroids with a half-life from <12 to 36 hours (Hu Citation2010). Therefore, the time points we used were appropriately selected to investigate their effects. Finally, both studies by Jules Elysee et al. (2011, 2012) reported the average outcomes of bilateral total knee arthroplasty, which slightly violates an assumption of independent observations. However, given the steroids used are systemic and have systemic bodily effects we feel that clinically the knees would be affected independently.

In summary our meta-analysis demonstrates that dosages between 50 and 75 mg of oral prednisolone equivalents of intermediate-acting systemic corticosteroids in knee arthroplasty provide a modest analgesic effect at 24 hours. Although we did not find any evidence of an increased risk of infection with corticosteroids our analyses are underpowered to make any definitive conclusions. However, Jørgensen et al. (Citation2017) published the largest cohort study to date (n = 3,927) investigating the effect of high-dose perioperative corticosteroids and found no differences in the incidence of deep infections between control and corticosteroid groups. We found no clinically significant analgesic effect for local steroids although this could be due to our analysis not being sufficiently powered. Monitoring of blood glucose should be conducted in high-risk patients, i.e. diabetics, given evidence of elevated blood sugars with steroids. Diabetic patients would need to be advised to self-monitor their blood sugars on discharge and have medical follow-up in the community. There is a clear requirement for further research to investigate systemic steroids in knee arthroplasty, as there are currently only sparse data on this issue. Additional work focusing on the effect of different dosages and specific corticosteroids would help develop consistent treatment guidance.

Multimodal analgesia such as local infiltrative analgesia has gained widespread popularity in recent years. Its usage as a basic pain treatment postoperatively could be improved by adjunctive use of systemic corticosteroids.

Supplementary data

Tables 1, 2, Figures 2, 4, 5, and an Appendix are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1391409

HRM wrote the manuscript with input from TWH, LS, DM, MHT, and HP. Statistical and methodological advice was provided from MHT. The search strategy was developed by HRM and Eli Harris from Bodleian libraries. All authors provided general advice regarding the study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. MHT is the guarantor of the study.

The authors would like to thank Eli Harris from Bodleian libraries for assisting in the search strategy development.

Acta thanks Henrik Husted and other anonymous reviwers for help with peer review of this study.

Supplementary data

Download PDF (2.7 MB)- Barletta J F. Clinical and economic burden of opioid use for postsurgical pain: Focus on ventilatory impairment and ileus. Pharmacotherapy 2012; 32 (9, pt. 2): 12S–8S.

- Chia S K, Wernecke G C, Harris I A, Bohm M T, Chen D B, MacDessi S J. Peri-articular steroid injection in total knee arthroplasty: A prospective, double blinded, randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty 2013; 28 (4): 620–3.

- Christensen C P, Jacobs C A, Jennings H R. Effect of periarticular corticosteroid injections during total knee arthroplasty: A double-blind randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009; 91 (11): 2550–5.

- De Oliveira G S, Almeida M D, Benzon H T, McCarthy R J. Perioperative single dose systemic dexamethasone for postoperative pain: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiology 2011; 115 (3): 575–88.

- Halawi M J, Grant S A, Bolognesi M P. Multimodal analgesia for total joint arthroplasty. Orthopedics 2015; 38 (7): e616–e25.

- Higgins J P, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. Updated March 2011. Section 7.7.3.5 Medians and interquartile ranges; http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/

- Husted H, Lunn T H, Troelsen A, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kristensen B B, Kehlet H. Why still in hospital after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty? Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (6): 679–84.

- Hu C. Steroid equivalence converter. MedCalc2010;//www.medcalc.com/steroid.html.

- Ikeuchi M, Kamimoto Y, Izumi M, Fukunaga K, Aso K, Sugimura N, et al. Effects of dexamethasone on local infiltration analgesia in total knee arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014; 22 (7): 1638–43.

- James Lind Alliance. Hip & knee replacement for osteoarthritis top 10 2017; http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/priority-setting-partnerships/hip-and-knee-replacement-for-osteoarthritis/top-10-priorities/.

- Jørgensen C C, Pitter F T, Kehlet H; Lundbeck Foundation Center for Fast-track Hip and Knee Replacement Collaborative Group. Safety aspects of preoperative high-dose glucocorticoid in primary total knee replacement. Br J Anaesth 2017; 119 (2): 267–75.

- Jules-Elysee K M, Lipnitsky J Y, Patel N, Anastasian G, Wilfred S E, Urban M K, et al. Use of low-dose steroids in decreasing cytokine release during bilateral total knee replacement. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2011; 36 (1): 36–40.

- Jules-Elysee KM, Wilfred S E, Memtsoudis S G, Kim D H, YaDeau J T, Urban M K, et al. Steroid modulation of cytokine release and desmosine levels in bilateral total knee replacement: A prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94 (23): 2120–7.

- Kim T W, Park S J, Lim S H, Seong S C, Lee S, Lee M C. Which analgesic mixture is appropriate for periarticular injection after total knee arthroplasty? Prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015; 23 (3): 838–45.

- Koh I J, Chang C B, Lee J H, Jeon Y-T, Kim T K. Preemptive low-dose dexamethasone reduces postoperative emesis and pain after TKA: A randomized controlled study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471 (9): 3010–20.

- Lunn T, Kristensen B, Andersen L, Husted H, Otte K, Gaarn-Larsen L, et al. Effect of high-dose preoperative methylprednisolone on pain and recovery after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Anaesthes 2011; 106 (2): 230–8.

- Machado G C, Maher C G, Ferreira P H, Pinheiro M B, Lin C-WC, Day RO, et al. Efficacy and safety of paracetamol for spinal pain and osteoarthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo controlled trials. BMJ 2015; 350: h1225.

- Meissner W, Coluzzi F, Fletcher D, Huygen F, Morlion B, Neugebauer E, et al. Improving the management of post-operative acute pain: Priorities for change. Curr Med Res Opin 2015; 31 (11): 2131–43.

- Mohammad H R, Trivella M, Hamilton T W, Strickland L, Murray D, Pandit H. An assessment of the impact of adjunctive perioperative corticosteroids for postoperative analgesia following elective knee surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 2017; 6 (1): 92

- Ng Y C S, Lo N N, Yang K Y, Chia S L, Chong H C, Yeo S J. Effects of periarticular steroid injection on knee function and the inflammatory response following unicondylar knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011; 19 (1): 60–5.

- Oderda G. Challenges in the management of acute postsurgical pain. Pharmacotherapy 2012; 32 (9pt2): 6S–11S.

- Oxman A D, Group G W. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004; 328 (19): 1490–4.

- Pang H N, Lo N N, Yang K Y, Chong H C, Yeo S J. Peri-articular steroid injection improves the outcome after unicondylar knee replacement: A prospective, randomised controlled trial with a two-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90 (6): 738–44.

- Romundstad L, Breivik H, Niemi G, Helle A, Stubhaug A. Methylprednisolone intravenously 1 day after surgery has sustained analgesic and opioid-sparing effects. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2004; 48 (10): 1223–31.

- Schünemann H J, Oxman A D, Higgins J P T, Vist G E, Glasziou P, Guyatt G H. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Chapter 11: Presenting results and "summary of findings" tables. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. Cochrane Collaboration; 2011, ed; http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/

- Seah V, Chin P, Chia S, Yang K, Lo N, Yeo S. Single-dose periarticular steroid infiltration for pain management in total knee arthroplasty: A prospective, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Singapore Med J 2011; 52 (1): 19–23.

- Tammachote N, Kanitnate S. Preoperative intravenous dexamethasone reduced pain after total knee arthroplasty. Pain Practice 2016; 16: 132.

- Tran J, Schwarzkopf R. Local infiltration anesthesia with steroids in total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review of randomized control trials. J Orthop 2015; 12: S44–S50.

- Tsukada S, Wakui M, Hoshino A. The impact of including corticosteroid in a periarticular injection for pain control after total knee arthroplasty: A double-blind randomised controlled trial. Bone Joint J 2016; 98-b (2): 194–200.

- Waldron N, Jones C, Gan T, Allen T, Habib A. Impact of perioperative dexamethasone on postoperative analgesia and side-effects: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 2012: aes431.

- Yue D B, Wang B L, Liu K P, Guo W S. Efficacy of multimodal cocktail periarticular injection with or without steroid in total knee arthroplasty. Chin Med J 2013; 126 (20): 3851–5.