Abstract

Background and purpose — To further improve the success of joint replacement surgery, attention needs to be paid to variations associated with improved or worsened outcomes. We investigated the association between the type of bone cement used and the risk of revision surgery after primary total hip replacement.

Methods — We conducted a prospective study of data from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales between April 1, 2003 and December 31, 2013. 199,205 primary total hip replacements performed for osteoarthritis where bone cement was used were included. A multilevel over-dispersed piecewise Poisson model was used to estimate differences in the rate of revision by bone cement type adjusted for implant type, head size, age, sex, ASA grade, and surgical approach.

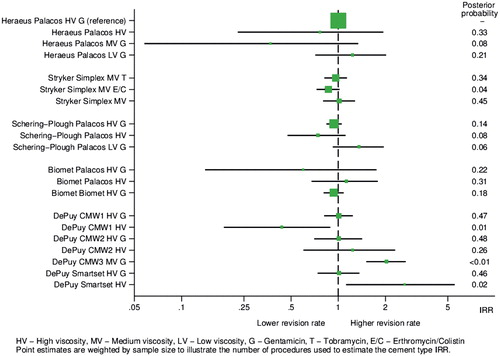

Results — The rate of revision was higher in DePuy CMW3 medium viscosity with gentamicin (IRR 2.0, 95% CI 1.5–2.7) and DePuy SmartSet high viscosity plain (IRR 2.7, 95% CI 1.1–5.5), and lower in DePuy CMW1 high viscosity plain (IRR 0.44, 95% CI 0.19–0.89) bone cements compared with Heraeus Palacos high viscosity with gentamicin. Revision rates were similar between plain and antibiotic-loaded bone cement.

Interpretation — The majority of bone cements performed similarly well, excluding DePuy SmartSet high viscosity and CMW3 high viscosity with gentamicin, which both had higher revision rates. We found no clear differences by viscosity or antibiotic content.

Cemented fixation of total hip replacements (THR) is associated with low rates of revision surgery in registry studies (Makela et al. Citation2014, NJR Steering Committee Citation2015b) in comparison with uncemented. There have been a limited number of observational reports describing the efficacy of different bone cements (BC) but it is unclear whether different BCs lead to different revision rates. For example, DePuy CMW3 (Havelin et al. Citation1995, Citation2000, Espehaug et al. Citation2002), DePuy CMW1 (Espehaug et al. Citation2002) and Sulfix (Herberts and Malchau 2000) BCs have previously been noted to be associated with higher failure rates.

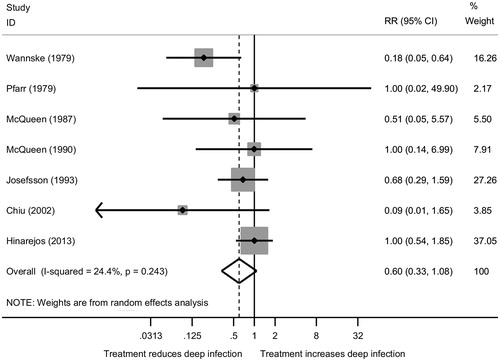

Crudely, BCs can be categorized by their viscosity and antibiotic content. The choice of viscosity is primarily determined by the type of operation and surgeon preference. There have been previous reports of increased failure rates with low-viscosity BCs (Herberts and Malchau Citation2000); however, conversely high-viscosity BCs have also been implicated (Espehaug et al. Citation2002). Antibiotic-loaded bone cements (ABC) are used in over 90% of all cemented fixations in countries in which cemented fixation is commonly used (Blom et al. Citation2003, Lindgren et al. Citation2014). The prophylactic routine use of ABC appears sensible; however, the evidence to support its use is heterogeneous. An observational study using data from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register showed lower rates of revision for primary THR using ABC with systemic antibiotics in comparison with plain BC with systemic antibiotics (Engesaeter et al. Citation2003). There are only a small number of randomized trials that have investigated the efficacy of ABC in humans (Pfarr and Burri Citation1979, Wannske and Tscherne Citation1979, Josefsson et al. Citation1981, McQueen et al. Citation1987, Citation1990, Chiu et al. Citation2002, Hinarejos et al. Citation2013). A recent systematic review concluded that antibiotic loading is justified in reducing PJI (Wang et al. Citation2013). However, the authors failed to include 1 eligible study in their meta-analysis (Pfarr and Burri Citation1979), and opted to use the short-term follow-up results from a trial as opposed to the long-term results (10 years), which were also available (Josefsson and Kolmert Citation1993). A sensitivity analysis (see Supplementary data) illustrates no effect of ABC (Table 1, see Supplementary data), and regression to the null over time (Figure 1, see Supplementary data).

We investigated the association between the type of BC used and the subsequent risk of revision in individuals undergoing primary THR, and whether any differences in revision rates could be explained by antibiotic content.

Methods

Using data from the National Joint Registry (NJR) for England, Wales and Northern Ireland, we investigated the association between BC brand, viscosity, antibiotic loading, and revision surgical procedure in patients undergoing THR. Reporting follows recommendations of the STROBE initiative (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) (von Elm et al. Citation2007).

Data source

The initial NJR dataset included 710,177 primary THR procedures performed in England and Wales between April 1, 2003 and December 31, 2013. Compliance, a measure of completeness comparing the number of procedures recorded in the NJR with implant sales, was low initially at 43% in 2003/04, but above 80% since 2005/06 and above 90% since 2007/08 (NJR Steering Committee Citation2015c). An audit of hip procedures for the financial year 2014/15 comparing hospital patient administration systems data with the NJR found that 4.3% of primary hip procedures and 8.1% of hip revisions were missing from the NJR (NJR Steering Committee Citation2016). Patient details for individuals with a traceable National Health Service (NHS) number (unique patient identifier) were passed to the NHS Personal Demographics Service, which provided date of death from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Primary procedures were then linked to revisions in the NJR with available patient identifiers (anonymized NHS number and side of procedure).

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

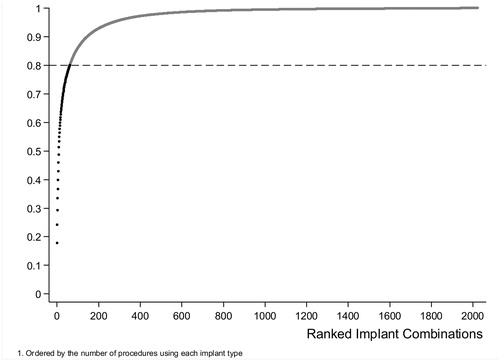

All cemented (cup and stem cemented), hybrid (uncemented cup and cemented stem), and reverse hybrid (cemented cup and uncemented stem) THRs, where the only recorded indication for surgery was osteoarthritis, were included in this study. Procedures where more than 1 type of BC was used, consent was withdrawn, the patient was untraceable, or with missing or inconsistent information on any of the study variables were excluded (). The analysis was restricted to procedures with implant combinations that were used in at least 500 procedures. This included the 62 most commonly used combinations (out of 2,023) and accounted for 80% of all recorded procedures (Figure 3, see Supplementary data). BCs that had less than 100 implantations were excluded.

Figure 2. Patient inclusion in/exclusion from the study.

a 44,179 individuals from England and Wales were not traceable. Northern Ireland joined the NJR on February 1, 2013; however, there was no tracing service available for patients in Northern Ireland, and 609 procedures were therefore excluded from the analysis.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome in this study was the first surgical revision of a primary THR. First surgical revision is determined using the mandatory registration of arthroplasty procedures in England and Wales. Loss to follow-up occurs with migration outside of England and Wales and when procedures are not entered onto the register. Linkability is estimated to be greater than 96% since 2008 (NJR Steering Committee Citation2015b). Left and right THRs in the same patient were considered to be independent and were counted as 2 observations, as the choice of prostheses and BCs between sides was not constrained to be the same.

The follow-up time from the date of the primary procedure to either the first revision or censoring (death or end of followup) was calculated using linked data from the ONS. The maximum possible follow-up time was 11 years.

Exposure

The primary exposure in this study was the use of polymethylmethacrylate BC to achieve fixation of at least 1 implant in the total hip replacement. The BCs (regardless of volume, mixing system, or delivery mechanism) were grouped into 9 brands (). Cement type was further sub-classified based on the manufacturer-reported viscosity (high (HV), medium (MV) or low (LV)), and antibiotic content.

Confounders

The primary confounding factor was implant type, defined using: stem, head, and cup combinations. Other confounding factors also included in the analysis were age (40–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75–85, and >85 years), sex, ASA grade (graded 1–4), implant head size (22.25 mm, 26 mm, 28 mm, 30–32 mm, and >36 mm), and surgical approach (“posterior” or “other”).

Statistics

The crude revision rate and prosthesis time incidence rate (PTIR; rate per 1,000 prosthesis-years of follow-up) of revision by BC type are reported. A multilevel over-dispersed piecewise Poisson model was used to estimate differences in the rate of revision by BC type. Multilevel modelling was used as it provides an efficient and transparent method of controlling for confounding factors either in the random or fixed-effects structure, whilst allowing for violations to key modelling assumptions, i.e. over-dispersion. Over-dispersion was controlled by the inclusion of a hyper-variance parameter within the random effects. Control for the primary confounding factor was achieved by matching procedures using the same implant combinations together and then investigating the difference in BC types. The length of prosthesis follow-up was included in the model via an offset parameter. A piecewise approach was adopted to allow for the time varying risk of revision; < 6 months, 6 months to 1 year, 1 year to 5 years, and >5 years. Missing data are assumed to be missing at random, and therefore complete case analysis is assumed to be unbiased given the large sample size.

We adopted a progressive confounding adjustment strategy. The first model was minimally adjusted for implant type by the use of a grouping indicator in the random effects to preserve matching. We then compared this with models that were more fully adjusted for age, sex, ASA grade, surgical approach, and implant head size. These additional confounding factors were included as fixed effects. Results are reported with reference to Heraeus Medical Palacos HV BC with gentamicin (the most commonly used cement).

The analysis was performed using MLwiN 2.35 (Browne Citation2009, Rasbash et al. Citation2009) with the runmlwin command (Leckie and Charlton Citation2013) in Stata 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Models were estimated using Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods (Browne and Draper Citation2006). Results are reported as incidence rate ratios (IRR) with 95% credible intervals (CI) and directional posterior probabilities (p). Directional posterior probabilities are reported as opposed to p-values to avoid the commonly misheld interpretation of a p-value that it provides evidence that the parameter is the wrong side of the null hypothesis of no effect (Greenland and Poole Citation2013). Effective sample size (ESS) is also reported to indicate the amount of chain mixing.

Funding and potential conflicts of interest

AS is funded by an MRC Strategic Skills Fellowship MR/L01226X/1. The funder of this study had no role in the design and conduct of this study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

MRW has carried out teaching on programs organized and sponsored by orthopedic device companies and cement manufacturers (Heraeus, DePuy, and JRI). His institution (University of Bristol) has received money paid into a research fund for this teaching; no direct benefits have been received. JCJW is a member of the Experts Committee of Palacademy (educational foundation funded by Heraeus). He has received lecture/teaching fees for Palacademy-run courses.

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the National Joint Registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data access applications can be made to the National Joint Registry Research Committee.

Results

The initial NJR dataset included 710,177 primary THR procedures. Following application of the inclusion/exclusion criteria listed previously () there were 199,205 primary THR procedures remaining.

Descriptive results

The majority of procedures were carried out on women (65%); however, the distribution of age, ASA physical status, surgical approach, fixation, bearing surface, and head size were very similar between men and women ().

Table 2. Demographic and surgical characteristics at the time of the primary procedure

Table 3. Number of primary procedures, revisions, crude revision rate, and PTIR by cement type

Of the 199,205 included primary THRs, 2,494 (1.25%) had a linked revision (). The total follow-up time for all procedures was 813,034 prosthesis years. The overall PTIR of revision was 3.07/1,000 prosthesis-years. The average followup time for a procedure was 4.08 years (Table 4, see Supplementary data).

Heraeus Medical Palacos HV BC with gentamicin was used in 49% of all procedures and had a PTIR of 3.29/1,000 prosthesis-years. DePuy SmartSet HV plain BC had the highest PTIR at 7.36/1,000 prosthesis-years, followed by DePuy CMW3 MV BC with gentamicin at 6.21/1,000 prosthesis years.

Multilevel over-dispersed piecewise Poisson regression model

Similar results were seen in the minimally and fully adjusted models (Table 5, see Supplementary data). For the majority of cements, in the fully adjusted model, there was no evidence of a difference in revision rate when compared with Heraeus Palacos HV with gentamicin, i.e. the CI includes the null. However, the rate of revision appears to be 103% higher in DePuy CMW3 MV with gentamicin (IRR 2.0, CI 1.5–2.7) and 165% higher in DePuy SmartSet HV plain (IRR 2.7, CI 1.1–5.5) BCs respectively. However, the revision rate using DePuy CMW1 HV plain BC is 56% lower (IRR 0.44, CI 0.19–0.89) compared with the referent. The IRR (with CI), in the fully adjusted model, for all cement types, are presented using a forest plot in . When each ABC was compared with its plain BC variant () there was no evidence of an increased risk of revision with the use of plain BC. In addition, there were no clear differences in the reason for revision comparing ABC and plain BC (Table 6, see Supplementary data). Similarly, the evidence of an effect of HV vs. MV and LV is minimal, with no clear association within or between brands.

Figure 4. Incident rate ratio (95% CI) of revision surgery comparing different bone cements with Heraeus Palacos HV + gentamicin. Abbreviations are G = gentamicin, T = tobramycin, E/C = erythromycin/colistin, HV = high, MV = medium, LV = low viscosity. Point estimates are weighted by sample size to illustrate the number of procedures to estimate the cement type IRR.

Discussion

This study has demonstrated in 199,205 primary hip replacement procedures that a small number of BCs are associated with an increased risk of revision surgery. Using the most commonly used BC as our reference (Heraeus-Medical Palacos HV with gentamicin) and adjusting for confounding factors (age, sex, ASA grade, surgical approach, and implant head size), we have demonstrated there is an increased risk of revision surgery with DePuy CMW3 MV with gentamicin and DePuy SmartSet HV plain BCs. DePuy CMW1 HV plain BC demonstrated a reduced risk of revision. There are no clear patterns of failure associated with BC viscosity. Most notably the Stryker Simplex MV family of cements perform very similarly in comparison with the 3 most commonly used HV cements (Heraeus Palacos HV, Schering-Plough Palacos HV, and Biomet HV). Similarly, there is a surprising lack of difference between ABCs and plain BCs. This consistency is evident across all 4 manufacturers, with the exception of DePuy CMW1 HV plain, which outperforms the antibiotic-loaded variant, and DePuy SmartSet HV with gentamicin, which outperforms the plain variant.

Whilst this study is significantly larger than many of the previous studies investigating BCs, it confirms the previous findings of the Nordic registries, which suggest DePuy CMW3 has a higher revision rate than the reference BC (Havelin et al. Citation1995, Citation2000, Espehaug et al. Citation2002). In the Nordic registries DePuy CMW3 was previously described as LV (Herberts and Malchau Citation2000), but in the data supplied to NJR it is described by the manufacturer as MV. Conversely we have found the

DePuy CMW1 HV plain BC significantly outperforms the most frequently used BC, which is contradictory to previous reports (Espehaug et al. Citation2002). This discrepancy may be due the restriction of the previous analysis to Charnley THRs, which make up a small proportion of the constructs included in this analysis and use a different fixation strategy for the stem (Learmonth Citation2006) than the majority of the cemented constructs included here (NJR Steering Committee Citation2015b). However, it is probably prudent to interpret the evidence of superiority for this BC cautiously given the relatively small number of procedures in which it is used.

The level of homogeneity in revision rates associated with different BCs is surprising, specifically with respect to the performance of ABC when compared with plain BC. We would expect the use of plain BC to lead to an excess of revision due to PJI. Given that this does not seem to be the case, it calls into question the prudence of such widespread use of ABC. The use of ABC in the UK is highly prevalent, with over 95% (90% in the NJR overall (NJR Steering Committee Citation2015a)) of prostheses in this sample using ABC, strongly suggesting that it is not being used in a selective way by surgeons depending on any risk assessment of PJI. However, the use of ABC has potential consequences including antibiotic resistance and excess treatment costs. Whilst the current rate of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections in this cohort is relatively low (Hickson et al. Citation2015), we do not know if this will persist.

Including antibiotics within BC is supposed to reduce the risk of PJI and therefore revision surgery. However, it is not clear whether ABC—with or without the concomitant use of systemic antibiotics—reduce the risk of infection after total joint replacement (see Supplementary data). Lack of contemporary evidence in favor of the use of ABC could be explained by other perioperative effects that influence the risk of PJI, such as reduced operating time and increased use of laminar flow theatres over the period of interest. Given the similar number of revisions due to PJI in ABC compared with plain BC in this sample, it seems to suggest that contemporary evidence of efficacy is lacking. Registry data tend to underestimate the number of revisions due to infection (Gundtoft et al. Citation2016), although as we have used all-cause revision as our endpoint this should not affect our main results. Given the potential to induce antibiotic-resistant infections (Hope et al. Citation1989) and increased costs, the widespread use of ABC must be evidence based (WHO Citation2001, Larson Citation2007). The list price cost differential (excluding sales tax) between ABC and the plain BC variant for the reference group in this study (Heraeus Palacos HV BC) is £58 (USD 79) for patients undergoing cemented THR, and £39 (USD 53) in patients undergoing hybrid THR (assuming 2 x 40g BC packets for stem fixation and 1 x 40g BC packet for cup fixation; https://my.supplychain.nhs.uk/Catalogue/browse/65/bone-cement-and-mixing-devices). As approximately 50% of all THRs (n = 80,000) in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland in 2014 used BC the potential annual savings are substantial (NJR Steering Committee Citation2015b). Furthermore, if the prolific use of ABC may lead to an increase in the number of antibiotic resistant infections the cost of treating these infections must also be considered. Parvizi et al. (Citation2010) reported that mean excess cost of treating infection caused by methicillin-resistant organisms was USD 32,181 in 2010.

Strengths

This study is the largest in vivo systematic investigation of the association between BC and revision surgery following primary THR. The unique design of the study, i.e. matched cohort study, allowed us to effectively control for the association between the prosthetic implant and risk of revision. By explicitly comparing revision rates within the same implant combinations we have removed the largest source of confounding. Furthermore, the NJR is one of the largest registers of arthroplasty in the world and the heterogeneous use of BC and prosthetic implants in England and Wales has allowed us to explore the efficacy of BC in a wide variety of contexts. Similarly the contemporary basis of the data strengthens the face validity, with operating practices being more consistent in the last 10 years.

Limitations

Despite the large size of the database, half of cases in which BC was used were Heraeus Medical Palacos HV with gentamicin. Therefore, the power to detect any differences in some of the less popular BCs is smaller. Given the magnitude of the effects reported and the length of the 95% credible intervals, we believe this is a fair representation of the performance of different BC currently used. The overall revision rate in our data is lower than the revision rate for cemented implants within the Nordic registries and the NJR. The NJR also has a lower revision rate for cemented procedures at 5 years than the Nordic registries. We have excluded from our analyses metal-on-metal procedures, which are known to have a higher revision rate. We also restricted our analyses to the most used implant combinations, which we would hope would be implant types with lower revision rates. Despite the NJR being one of the largest registries in the world, with very good compliance and data completion rates (NJR Steering Committee Citation2015b), as with all studies the potential for revision surgeries to be missing not at random has the potential to bias results. Similarly, residual confounding is still possible despite the rigorous methods adopted.

The outcome for this study was all-cause revision. It would also be interesting to conduct analyses on cause-specific revision, particularly when investigating the effect of adding antibiotic to bone cement where the main difference would be expected to be for infections. However, as the revision rate is low we feel that such an analysis would likely be underpowered and therefore not provide meaningful results. Lastly we cannot exclude the possibility that surgeons added antibiotics to plain BC products in theatre, which is not documented in the NJR.

In summary, the majority of BCs performed similarly well, excluding DePuy SmartSet HV and CMW3 HV with gentamicin, which both had higher revision rates. We found no clear differences by viscosity or by antibiotic content.

Supplementary data

Tables 1, 4–6, and Figures 1 and 3 are available in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1393224

JCJW, MRW and AWB conceived the study. LT-L, AS, AWB, JCJW, and MRW designed the study. AS and MRW reviewed the published work and wrote the first draft of the article. LT-L and AS performed the data analysis. All authors interpreted data and wrote the report.

AS and LT-L had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The data were extracted by Northgate (Hemel Hempstead, UK).

We thank the patients and staff of all the hospitals who have contributed data to the National Joint Registry. We are grateful to the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership, the National Joint Registry Steering Committee, and staff at the National Joint Registry for facilitating this work. The views expressed represent those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Joint Registry Steering Committee or Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership, who do not vouch for how the information is presented.

Acta thanks Søren Overgaard and other anonymous reviwers for help with peer review of this study.

IORT_A_1393224_SUPP.PDF

Download PDF (216.7 KB)- Blom A W, Taylor A H, Pattison G, Whitehouse S, Bannister G C. Infection after total hip arthroplasty: The Avon experience. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2003; 85 (7): 956–9.

- Browne W J. MCMC Estimation in MLwiN v2.1. Centre for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol, 2009.

- Browne W J, Draper D. A comparison of Bayesian and likelihood-based methods for fitting multilevel models. Bayesian Anal 2006; 1 (3): 473–513.

- Chiu F Y, Chen C M, Lin C F, Lo W H. Cefuroxime-impregnated cement in primary total knee arthroplasty: A prospective, randomized study of three hundred and forty knees. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002; 84 (5): 759–62.

- Engesaeter L B, Lie S A, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Vollset S E, Havelin L I. Antibiotic prophylaxis in total hip arthroplasty: Effects of antibiotic prophylaxis systemically and in bone cement on the revision rate of 22,170 primary hip replacements followed 0–14 years in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop Scand 2003; 74 (6): 644–51.

- Espehaug B, Furnes O, Havelin L I, Engesaeter L B, Vollset S E. The type of cement and failure of total hip replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84 (6): 832–8.

- Greenland S, Poole C. Living with p values: Resurrecting a Bayesian perspective on frequentist statistics. Epidemiology 2013; 24 (1): 62–8.

- Gundtoft P H, Pedersen A B, Schonheyder H C, Overgaard S. Validation of the diagnosis “prosthetic joint infection”in the Danish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Bone Joint J 2016; 98 (3): 320–25.

- Havelin L I, Espehaug B, Vollset S E, Engesaeter L B. The effect of the type of cement on early revision of Charnley total hip prostheses: A review of eight thousand five hundred and seventy-nine primary arthroplasties from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995; 77 (10): 1543–50.

- Havelin L I, Engesaeter L B, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Lie S A, Vollset S E. The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register: 11 years and 73,000 arthroplasties. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71 (4): 337–53.

- Herberts P, Malchau H. Long-term registration has improved the quality of hip replacement: A review of the Swedish THR Register comparing 160,000 cases. Acta Orthop Scand 2000; 71 (2): 111–21.

- Hickson C J, Metcalfe D, Elgohari S, Oswald T, Masters J P, Rymaszewska M, Reed M R, Sprowson A P. Prophylactic antibiotics in elective hip and knee arthroplasty: An analysis of organisms reported to cause infections and national survey of clinical practice. Bone Joint Res 2015; 4 (11): 181–9.

- Hinarejos P, Guirro P, Leal J, Montserrat F, Pelfort X, Sorli M L, Horcajada J P, Puig L. The use of erythromycin and colistin-loaded cement in total knee arthroplasty does not reduce the incidence of infection: A prospective randomized study in 3000 knees. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95 (9): 769–74.

- Hope P G, Kristinsson K G, Norman P, Elson R A. Deep infection of cemented total hip arthroplasties caused by coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1989; 71 (5): 851–5.

- Josefsson G, Kolmert L. Prophylaxis with systematic antibiotics versus gentamicin bone cement in total hip arthroplasty: A ten-year survey of 1,688 hips. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993; (292): 210–14.

- Josefsson G, Lindberg L, Wiklander B. Systemic antibiotics and gentamicin containing bone cement in the prophylaxis of postoperative infections in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1981; (159): 194–200.

- Larson E. Community factors in the development of antibiotic resistance. Annu Rev Public Health 2007; 28: 435–47.

- Learmonth I D. Total hip replacement and the law of diminishing returns. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88 (7): 1664–73.

- Leckie G, Charlton C. runmlwin: A program to run the MLwiN multilevel modeling software from within Stata. J Stat Softw 2013; 52 (11): 1–40.

- Lindgren J V, Gordon M, Wretenberg P, Karrholm J, Garellick G. Validation of reoperations due to infection in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014 15 (1): 384–9.

- Makela K T, Matilainen M, Pulkkinen P, Fenstad A M, Havelin L, Engesaeter L, Furnes O, Pedersen A B, Overgaard S, Karrholm J, Malchau H, Garellick G, Ranstam J, Eskelinen A. Failure rate of cemented and uncemented total hip replacements: Register study of combined Nordic database of four nations. BMJ 2014; 348: f7592.

- McQueen M, Littlejohn A, Hughes S P. A comparison of systemic cefuroxime and cefuroxime loaded bone cement in the prevention of early infection after total joint replacement. Int Orthop 1987; 11 (3): 241–3.

- McQueen M M, Hughes S P, May P, Verity L. Cefuroxime in total joint arthroplasty: Intravenous or in bone cement. J Arthroplasty 1990; 5 (2): 169–72.

- NJR Steering Committee. Bone cement types used in primary hip replacement procedures. 2015a; http://www.njrreports.org.uk/hips-primary-procedures-surgical-technique/H12v1NJR?reportid=363414BB-6BA2-44CF-A764-87E8009E11D9&defaults=DC__Reporting_Period__Date_Range=“2016|NJR2015”,H__JYS__Filter__Calendar_Year__From__ To=“MIN-MAX”,H

- NJR Steering Committee. National Joint Registry for England, Wales and Northern Ireland: 12th Annual Report. 2015b; http://www.njrcentre.org.uk/njrcentre/Portals/0/Documents/England/Reports/12th%20annual%20 report/NJR%20Online%20Annual%20Report%202015.pdf.

- NJR Steering Committee. Supporting data quality NJR strategy 2014/16. 2015c; http://www.njrcentre.org.uk/njrcentre/Portals/0/Documents/England/Data quality and strategy/NJR Supporting data quality-strategy 14-16 online.pdf

- NJR Steering Committee. 2015/16 (FY2014/15) Trust and health board compliance results. 2016; http://www.njrcentre.org.uk/njrcentre/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket =4nVbaVZvCqg%3d&tabid =1435&portalid =0&mid =2539.

- Parvizi J, Pawasarat I M, Azzam K A, Joshi A, Hansen E N, Bozic K J. Periprosthetic joint infection: The economic impact of methicillin-resistant infections. J Arthroplasty 2010; 25(6Suppl): 103–7.

- Pfarr B, Burri C. Prospective study on the effect of gentamycin-Palacos in 200 total hip prostheses. Aktuelle Probl Chir Orthop 1979; (12): 207–10.

- Rasbash J, Charlton C, Browne W J, Healy M, Cameron B. MLwiN Version 2.1. Centre for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol, 2009.

- von Elm E, Altman D G, Egger M, Pocock S J, Gotzsche P C, Vandenbroucke J P, STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007; 370 (9596): 1453–7.

- Wang J, Zhu C, Cheng T, Peng X, Zhang W, Qin H, Zhang X. A systematic review and meta-analysis of antibiotic-impregnated bone cement use in primary total hip or knee arthroplasty. PLoS One 2013; 8 (12): e82745.

- Wannske M, Tscherne H. Results of prophylactic use of Refobacin-Palacos in implantation of endoprostheses of the hip joint in Hannover. Aktuelle Probl Chir Orthop 1979; (12): 201–5.

- WHO. WHO Global Strategy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance. WHO/CDS/CSR/DRS/2001.2. Geneva: WHO, 2001.