Abstract

Background and purpose — The number of revision total knee arthroplasties (TKA) is continuously increasing, leading to a growing need for reliable management of metaphyseal bone loss. We evaluated patients operated with a TKA using metal metaphyseal sleeves for bone defects with a minimum 5-year follow-up.

Patients and methods — 37 patients had been operated on. 3 patients died and 3 patients were lost during follow-up. Of the 31 remainders (20 women), 9 had been operated on with a primary TKA and 22 with a revision TKA at the index surgery. The mean age at surgery was 69 (54–89) years and the mean follow-up time was 7.4 (5–12) years. Bone defects were classified according to the Anderson Orthopaedic Research Institute classification (tibia: type I n = 9, type II n = 5 and type III n = 17; femur: type I n = 12, type II n = 3 and type III n = 16).

Results — At final follow-up one-third experienced an improvement concerning walking aids and walking distance. Except for 1 patient, all had full extension and a mean knee flexion of 110 (90–140) degrees. VAS pain at rest was 13 (SD 25) and on movement 30 (SD 31). 7 patients were reoperated due to: infection (n = 4), periprosthetic fracture (n = 1), skin necrosis (n = 1), and wound rupture (n = 1). The cumulative 5-year survival rate for reoperation was 77% (CI 63–92) and for revision 97% (CI 91–100). At the time of final follow-up, the sleeves showed good osseointegration with no signs of progressive radiolucency or migration.

Interpretation — Titanium sleeves are a promising option in managing difficult cases with metaphyseal bone defects in TKA, providing a stable construct with good medium-term radiographic outcome

The use of metal metaphyseal sleeves in revision of total knee arthroplasties (TKA) with metaphyseal bone loss has gained in popularity during recent years, taking advantage of osseous integration and providing a stable scaffold for joint reconstruction (Jones et al. Citation2001). Short-term results (< 5 years follow-up) suggest that metaphyseal sleeves may offer a good solution addressing bone defects with a reliable fixation on both the tibial and femoral side (Agarwal et al. Citation2013, Alexander et al. Citation2013, Barnett et al. Citation2014, Huang et al. Citation2014, Bugler et al. Citation2015, Graichen et al. Citation2015, Dalury and Barrett Citation2016, Chalmers et al. Citation2017, Fedorka et al. Citation2017). However, there is a lack of longer follow-up studies. We investigated the clinical and radiographic outcome of patients operated with metal metaphyseal sleeves in TKA with a minimum of 5-year follow-up.

Patients and methods

In this retrospective study, we evaluated 37 patients operated with either an S-ROM Noiles Rotating Hinge Revision Knee System (DePuy Synthes, Warsaw, IN, USA) (n = 21) or a PFC Sigma TC3 Revision Knee System (DePuy Synthes, Warsaw, IN, USA) (n = 10) using metal metaphyseal sleeves. Cement was used for the tibial plateau and the femoral shield, but not for the stems and sleeves (hybrid fixation) (Agarwal et al. Citation2013). The procedures were performed during 2003 and 2010 giving a minimum follow-up of 5 years for all patients. At follow-up, 3 patients had died and another 3 were lost. The mean follow-up time after surgery of the remaining 31 patients (20 females) was 7.4 (5–12) years and the mean age at surgery was 69 (54–89) years. The majority of the patients had primary osteoarthritis and inflammatory arthritis as their diagnosis. Tibial sleeves were used in 28 and femoral sleeves in 20 cases. All knees were operated with stems, apart from 3 femoral and 2 tibial cases where a sleeve was used without a stem. In 9/31 the index operation was performed as a primary TKA and in 22/31 cases as a revision (, ).

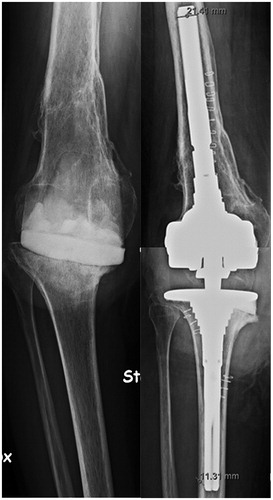

Figure 1. Pre- and postperative radiographs of a 56-year-old man who underwent a 2-stage revision for deep periprosthetic infection for which femoral and tibial metaphyseal sleeves were used at the time of reimplantation.

Table 1. Patient characteristics at index surgery (n = 31)

Table 2. Patient characteristics at follow-up (n = 31)

Table 3. Radiolucent lines at follow-up

Data collection included baseline demographic information, diagnosis, and indications for surgery. At final follow-up, we evaluated pain at rest and movement (visual analogue scale [VAS], 0–100). Moreover, clinical evaluation included BMI, range of motion (ROM), knee stability, and patellar tracking. Both the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) (Roos and Lohmander Citation2003) and the EuroQol (EQ-5D) (Brooks Citation1996) were assessed. Moreover, we documented whether there had been any changes concerning the use of walking aids or walking distance since the index surgery.

Anterior-posterior and lateral radiographs of the knees were reviewed by the same musculoskeletal radiologist (MCW). Tibial and femoral bone defects were classified according to the Anderson Orthopaedic Research Institute (AORI) classification (Engh and Ammeen Citation1999) using preoperative radiographs. At follow-up, radiolucent lines were graded with the Knee Society Rating System (Ewald Citation1989). Radiographs were assessed for osseous in-growth, signs of loosening defined as implant migration or a 2 mm or greater radiolucency along the entirety of the component, fracture, or any other subtle complication (Alexander et al. Citation2013). Deviation from the optimal joint line was assessed using the method described by Sadaka et al. (Citation2015). Skyline patellar radiographs were compared postoperatively and at follow-up. At follow-up, patellar thickness was subjectively assessed as being unchanged, reduced by <50%, or reduced by >50% compared with the index operation.

Statistics

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed with reoperation and revision as the endpoint. Reoperation included all types of new surgical procedures in the same knee following the index operation. Revision was defined as a new operation in a previously resurfaced knee in which 1 or more of the components were exchanged, removed, or added. Life-tables and survival functions with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. All statistical analyses were performed using the PASW statistics package version 18 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

This study was performed according to the Helsinki Declaration and it was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (Dnr 2010/1584-31/1). The study was financially supported by institutional funds only. All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Results

Clinical outcome ()

At latest follow-up, the mean VAS pain at rest was 13 (SD 25) and on movement 30 (SD 31). End-of-stem pain was found in 5/31 patients in the femur and in 3/31 patients in the tibia. Except for 1 patient, all had full extension and a mean knee flexion of 110 (90–140) degrees. 28/31 knees were considered stable and patellar tracking was adequate in 24/31 cases. About one-third of the cases experienced an improvement concerning walking aids and walking distance at final follow-up.

Failures and survival

No sleeve-related complications were noted. 7 patients were reoperated: 2 due to early infections within weeks, 2 due to septic infections after 5 years, and 1 patient suffered a periprosthetic fracture after 2 years (fracture below the tibial stem). 1 patient was treated with negative-pressure wound therapy due to skin necrosis and there was 1 reoperation due to an early traumatic wound rupture. The overall 5-year prosthesis survival was 77% (CI 63–92) with the endpoint reoperation and 97% (CI 91–100) with the endpoint revision.

Radiographic outcome ()

Radiographs at latest follow-up showed stable position of the sleeves, i.e. no implant migration was seen. Although there were minor radiolucent lines (1 mm) detectable in a few sleeves, no radiolucency along an entire component was detected. The mean deviation from the optimal joint line was 5 (–5 to 14) mm. An acceptable joint line, defined as ±8 mm from the original joint line (Partington et al. Citation1999) was achieved in 20/28 cases. In 8/28 cases, the joint line was elevated >8 mm. In 3 cases radiographic landmarks were missing and therefore evaluation of the joint line was not possible. Patellar thickness at follow-up was unchanged in 16/31 cases, reduced by <50% in 6/31 cases, and reduced by >50% in 9/31 cases.

Discussion

Metal metaphyseal sleeves in TKA surgery have been introduced to achieve a stable construct in patients with significant bone deficiency. Sleeves allow cementless fixation to host bone to overcome extensive metaphyseal defects. This is the first medium-term study (mean follow-up 7.4 years) with both clinical and radiographic data on cementless metaphyseal sleeves.

Clinical follow-up in our patients showed a KOOS pain of 61 and VAS pain between 13 (rest) and 30 (movement). As expected, our results are worse compared with patient outcome data of 2,216 primary TKAs 1 year after surgery (KOOS pain 80 and VAS pain 18) (Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register Citation2015). We found an adequate ROM and about one-third of the patients experienced an improvement concerning walking aids and walking distance. This is in line with several other reports on patients operated with metal sleeves documenting promising clinical short-term results such as patient-reported outcome scores and ROM (Agarwal et al. Citation2013, Alexander et al. Citation2013, Barnett et al. Citation2014, Huang et al. Citation2014, Bugler et al. Citation2015, Graichen et al. Citation2015).

7 patients had been reoperated at final follow-up, which translated into a 5-year survival rate of 77% for reoperation and 97% for revision as the endpoint. Graichen et al. (Citation2015) reported a survival rate of the metaphyseal sleeves of 98% after 3.6 years (121 patients) and Huang et al. (Citation2014) documented a short-term survivorship of 93% after 2.4 years (79 patients). Chalmers et al. (Citation2017) analyzed 280 patients operated with cemented and cementless sleeves and found a 5-year survival for aseptic loosening of 96% and 100% for femoral and tibial sleeves.

The majority of our patients had large tibial and/or femoral osseous defects (AORI Type II and III). However, we also used sleeves in some cases with minor defects (AORI Type I) that could have been addressed using a combination of bone grafting, modular augments, and cement (Engh and Ammeen Citation1999). We did not find any progressive radiolucent lines around the femoral or tibial metaphyseal sleeves or radiographic migration of the components. Graichen et al. (Citation2015) reported good osseointegration of the sleeves in 96% of cases after 3.6 years (121 patients). Other reports with short-term follow-up showed favorable radiographic results with stable, osseointegrated sleeves without component migration or significant osteolysis (Jones et al. Citation2001, Radnay and Scuderi Citation2006, Agarwal et al. Citation2013, Alexander et al. Citation2013, Barnett et al. Citation2014, Huang et al. Citation2014, Bugler et al. Citation2015, Graichen et al. Citation2015, Dalury and Barrett Citation2016, Fedorka et al. Citation2017).

Resurfacing of the patellofemoral joint was undertaken in only 1 of our patients. We did not find that patellofemoral symptoms (pain) were a significant problem at final follow-up. However, patellar thickness decreased radiographically during the follow-up in about half of the patients of whom 6 had a subluxated or dislocated patella. This subgroup had more pain, worse EQ-5D, and were less satisfied compared with those with patellar tracking (data not shown). Other authors described a high rate of patellofemoral symptoms in general (Bugler et al. Citation2015). They argued that this could be due to the high box on the TC3 femoral component and therefore advocated patellofemoral resurfacing routinely when using the TC3 femoral prosthesis. At follow-up, 7 out of 20 patients with an acceptable joint line and 6 out of 8 patients with an elevated joint line had a radiographic reduction of patellar thickness. This may suggest that this type of prosthesis causes a stress to the patella and that the stress is more pronounced in cases with joint line elevation. Pain, patellar tracking, EQ5D, and KOOS were similar between patients with or without joint line elevation (data not shown).

In our study, only 5 knees were operated using a metaphyseal sleeve without a stem. Bugler et al. (Citation2015) followed 34 patients operated with a sleeve during a revision procedure (mean follow-up 3.3 years). The authors used sleeves without stems in about half of all operations without any signs of early loosening. Agarwal et al. (Citation2013) reported 2 cases of early loosening in patients where a sleeve was implanted without a stem. Therefore, the authors recommended routine use of stems in all patients. Gøttsche et al. (Citation2016) followed 63 patients operated with sleeves without stems. After a minimum of 2-year follow-up, 62 of the 63 patients had radiographic ingrowth with the prostheses still in place. However, about half of the patients had non-optimal knee alignment with significantly more pain, less satisfaction and lower patient outcome scores compared with cases that had adequate knee alignment. The authors recommended the use of stems in combination with sleeves to improve alignment and clinical outcome. Morgan-Jones et al. (Citation2015) highlighted the importance of 3 anatomical zones (epiphysis, metaphysis, and diaphysis) for preoperative planning and implant selection of revision TKA cases. The authors suggested that solid fixation should be obtained in at least 2 of 3 zones. When using metaphyseal sleeves additional fixation in the diaphysis is advocated (Morgan-Jones et al. Citation2015).

Our study has several limitations, including the retrospective design. Our cohort is heterogeneous with varying indications (primary and revision TKA). We used 2 different prosthesis systems, 1 more constrained than the other. Moreover, we lack preoperative clinical data, such as pain scores, and we were not able to assess mechanical alignment because full-length standing radiographs were not available. Mulhall et al. (Citation2006) found that analyzing preoperative radiographs using the AORI classification usually results in an underestimation of the amount of bone loss. Therefore, some patients were more likely to have had worse bone defects than classified. Indication for implantation of a metaphyseal sleeve was made by the surgeon. The preferred method of measuring implant migration would have been RSA, which was not available for this study. Instead, we used the radiographic method recommended by the Knee Society, which indeed is a “rough” tool but gave us the opportunity to measure radiolucent lines/zones and patellar thickness. We did not perform a competing risk analysis. Competing risks such as death influence implant survival calculated according to Kaplan–Meier. Patients who die cannot be revised, and thus the risk of revision may be underestimated in elderly populations with long follow-up times and a relatively high mortality (Ranstam et al. Citation2011). The confidence intervals were wide, reflecting the relatively small sample size, thus the results should be interpreted with caution.

In summary, this is the first study on patients undergoing TKA with metal sleeves with minimum 5-year follow-up. We found a good clinical and radiographic outcome with a medium-term stable fixation. The rare occurrence of radiolucency around the sleeves suggests that these implants may be sufficient to decrease the stresses that contribute to failure.

MT, MH and RJW: planning, data analysis, statistics, writing, and editing of the manuscript. MCW: data analysis and editing of the manuscript.

Acta thanks Gijs Van Hellemondt and Anders Troelsen for help with peer review of this study.

- Agarwal S, Azam A, Morgan-Jones R. Metal metaphyseal sleeves in revision total knee replacement. Bone Joint J 2013; 95-B (12): 1640–4.

- Alexander G E, Bernasek T L, Crank R L, Haidukewych G J. Cementless metaphyseal sleeves used for large tibial defects in revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2013; 28 (4): 604–7.

- Barnett S L, Mayer R R, Gondusky J S, Choi L, Patel J J, Gorab R S. Use of stepped porous titanium metaphyseal sleeves for tibial defects in revision total knee arthroplasty: Short term results. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29 (6): 1219–24.

- Brooks R. EuroQol: The current state of play. Health Policy 1996; 37 (1): 53–72.

- Bugler K E, Maheshwari R, Ahmed I, Brenkel I J, Walmsley P J. Metaphyseal sleeves for revision total knee arthroplasty: Good short-term outcomes. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30 (11): 1990–4.

- Chalmers B P, Desy N M, Pagnano M W, Trousdale R T, Taunton M J. Survivorship of metaphyseal sleeves in revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2017; 32 (5): 1565–70.

- Dalury D F, Barrett W P. The use of metaphyseal sleeves in revision total knee arthroplasty. Knee 2016; 23 (3): 545–8.

- Engh G A, Ammeen D J. Bone loss with revision total knee arthroplasty: Defect classification and alternatives for reconstruction. Instr Course Lect 1999; 48: 167–75.

- Ewald F C. The Knee Society total knee arthroplasty roentgenographic evaluation and scoring system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989; (248): 9–12.

- Fedorka C J, Chen A F, Pagnotto M R, Crossett L S, Klatt B A. Revision total knee arthroplasty with porous-coated metaphyseal sleeves provides radiographic ingrowth and stable fixation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2017 Mar 17. [Epub ahead of print]

- Gøttsche D, Lind T, Christiansen T, Schrøder H M. Cementless metaphyseal sleeves without stem in revision total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2016; 136(12): 1761–6.

- Graichen H, Scior W, Strauch M. Direct, cementless, metaphyseal fixation in knee revision arthroplasty with sleeves: Short-term results. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30 (12): 2256–9.

- Huang R, Barrazueta G, Ong A, Orozco F, Jafari M, Coyle C, Austin M. Revision total knee arthroplasty using metaphyseal sleeves at short-term follow-up. Orthopedics 2014; 37 (9): e804–9.

- Jones R E, Barrack R L, Skedros J. Modular, mobile-bearing hinge total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001; (392): 306–14.

- Morgan-Jones R, Oussedik S I, Graichen H, Haddad F S. Zonal fixation in revision total knee arthroplasty. Bone Joint J 2015; 97-B (2): 147–9.

- Mulhall K J, Ghomrawi H M, Engh G A, Clark C R, Lotke P, Saleh K J. Radiographic prediction of intraoperative bone loss in knee arthroplasty revision. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 446: 51–8.

- Partington P F, Sawhney J, Rorabeck C H, Barrack R L, Moore J. Joint line restoration after revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999; (367): 165–71.

- Radnay C S, Scuderi G R. Management of bone loss: Augments, cones, offset stems. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 446: 83–92.

- Ranstam J, Karrholm J, Pulkkinen P, Makela K, Espehaug B, Pedersen A B, Mehnert F, Furnes O, group N s. Statistical analysis of arthroplasty data, II: Guidelines. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (3): 258–67.

- Roos E M, Lohmander L S. The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): From joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003; 1: 64.

- Sadaka C, Kabalan Z, Hoyek F, Abi Fares G, Lahoud J C. Joint line restoration during revision total knee arthroplasty: An accurate and reliable method. SpringerPlus 2015; 4: 736.

- Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. Annual Report 2015; http://www.myknee.se/en/.