Abstract

Background and purpose — Mobile-bearing total knee prostheses (TKPs) were developed in the 1970s in an attempt to increase function and improve implant longevity. However, modern fixed-bearing designs like the single-radius TKP may provide similar advantages. We compared tibial component migration measured with radiostereometric analysis (RSA) and clinical outcome of otherwise similarly designed cemented fixed-bearing and mobile-bearing single-radius TKPs.

Patients and methods — RSA measurements and clinical scores were assessed in 46 randomized patients at baseline, 6 months, 1 year, and annually thereafter up to 6 years postoperatively. A linear mixed-effects model was used to analyze the repeated measurements.

Results — Both groups showed comparable migration (p = 0.3), with a mean migration at 6-year follow-up of 0.90 mm (95% CI 0.49–1.41) for the fixed-bearing group compared with 1.22 mm (95% CI 0.75–1.80) for the mobile-bearing group. Clinical outcomes were similar between groups. 1 fixed-bearing knee was revised for aseptic loosening after 6 years and 2 knees (1 in each group) were revised for late infection. 2 knees (1 in each group) were suspected for loosening due to excessive migration. Another mobile-bearing knee was revised after an insert dislocation due to failure of the locking mechanism 6 weeks postoperatively, after which study inclusion was preliminary terminated.

Interpretation — Fixed-bearing and mobile-bearing single-radius TKPs showed similar migration. The latter may, however, expose patients to more complex surgical techniques and risks such as insert dislocations inherent to this rotating-platform design.

Mobile-bearing total knee prostheses (TKPs) were developed in the late 1970s in an attempt to increase function and improve implant longevity. The bearing was designed to articulate with both a congruent femoral component and a flat non-constrained tibial component, thereby minimizing both contact stresses at the implant–bone interface and polyethylene wear, which should ultimately reduce the occurrence of mechanical loosening (Callaghan et al. Citation2001, Mahoney et al. Citation2012).

The first—implant developer—long-term survival studies of such designs showed promising high survival rates and good clinical performance (Buechel et al. Citation2001, Callaghan et al. Citation2001, Buechel Citation2002, Citation2004). Contrarily, no superior results compared with fixed bearings were seen in a number of trials, large registry-based studies and meta-analyses (Pagnano et al. Citation2004, Namba et al. Citation2011, Mahoney et al. Citation2012, van der Voort et al. Citation2013, Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry 2015, Hofstede et al. Citation2015). Several trials assessing the migration pattern with radiostereometric analysis (RSA) found no superiority of either design on tibial component fixation (Hansson et al. Citation2005, Henricson et al. Citation2006, Pijls et al. Citation2012a, Tjornild et al. Citation2015) and even questioned whether the mobile bearing truly stays mobile in vivo (Garling et al. Citation2007). Furthermore, mobile-bearing arthroplasty is considered technically more challenging as less optimal ligament balancing increases the risk of insert dislocations, requiring revision surgery (Cho et al. Citation2010, Fisher et al. Citation2011, Namba et al. Citation2012). Nevertheless, the mobile-bearing design is marketed as an appealing choice for especially young and active patients who demand maximum function and implant longevity (Jolles et al. Citation2012, Mahoney et al. Citation2012, Tjornild et al. Citation2015).

Over time, modern TKPs have substantially improved in design, quality of materials (particularly the polyethylene) and fixation methods. In contrast to most conventional designs that have several axes of femoral rotation during flexion, the femoral component of the ‘single-radius’ TKP rotates about a single axis and should thereby reduce contact stress (Molt et al. Citation2012, Wolterbeek et al. Citation2012). The fixed-bearing variant of this single-radius design allows for some axial rotation during deep flexion with minimal constraint forces (Molt et al. Citation2012). Thus, the theoretical advantages of this fixed-bearing single-radius design might come close to the concepts of mobile-bearing designs, but without the associated risks like insert dislocations.

There are to our knowledge no studies comparing mobile-bearing and fixed-bearing single-radius TKPs, except for a previous report on 1-year migration and kinematics on the first 20 patients of this trial (Wolterbeek et al. Citation2012). We now present medium-term follow-up results of all included patients and compare tibial component migration and clinical outcomes of similarly designed mobile-bearing and fixed-bearing cemented single-radius TKPs.

Patients and methods

This randomized controlled trial was conducted at the Leiden University Medical Center (an academic tertiary referral center) between April 2008 and February 2010. Patients received either mobile-bearing or fixed-bearing components of an otherwise similarly designed cemented posterior stabilized Triathlon TKP (Stryker, Mahwah, NJ, USA). The rotating-platform mobile-bearing design additionally has a locking O-ring, which allows axial rotation about a central post (Wolterbeek et al. Citation2012). The arthroplasties were performed by three experienced knee surgeons or under their direct supervision, using the appropriate guidance instruments following the manufacturer’s instructions. In all patients, the components were cemented first, after which the insert was mounted. Pulsatile lavage of the osseous surface was undertaken before applying bone cement (Palacos R cement, Heraeus-Kulzer GmbH, Hanau, Germany). For more details regarding patients, randomization and prostheses, see Wolterbeek et al. (Citation2012).

Follow-up

Baseline characteristics, including the Knee Society Score (KSS) and hip–knee–ankle angle (HKA) measurements (with varus <180°) were assessed 1 week before surgery. Postoperative evaluations including RSA radiographs were performed the first or second day after surgery, before weight bearing. Subsequent RSA and clinical examinations including KSS scores were scheduled at 6 months, 1 year and annually thereafter. HKA measurements were repeated at the 1-year follow-up.

Radiostereometric analysis

To accurately measure tibial component migration, radiostereometric analysis measurements were performed according to the RSA guidelines (ISO 16087:2013(E) Citation2013). At each examination, the patient was in a supine position with the calibration cage (Carbon Box, Leiden, The Netherlands) under the table in a uniplanar setup. Migration was analyzed using Model-based RSA, version 4 (RSAcore, LUMC, Leiden, the Netherlands). Positive directions along and about the orthogonal axes are: medial on transverse (x-)axis, cranial on longitudinal (y-)axis and anterior on sagittal (z-)axis for translations and anterior tilt (x-axis), internal rotation (y-axis) and valgus tilt (z-axis) for rotations (Valstar et al. Citation2005). The maximum total point motion (MTPM), which is the length of the translation vector of the point on the tibial component that has moved most, was defined as the primary outcome.

Sample size

RSA measurement error of less than 0.5 mm was expected (Valstar et al. Citation2005). If the true difference in MTPM between fixed-bearing and mobile-bearing TKPs is 0.5 mm, 17 patients were required to detect this difference with alpha 0.05 and power 0.80. To account for loss to follow-up, the intention was to randomize 20 patients to each group.

Statistics

The original primary endpoint (Wolterbeek et al. Citation2012) was registered as a difference in MTPM between groups after 1-year follow-up on the first 20 enrolled patients. For this medium-term follow-up analysis, we changed the primary endpoint—prior to data analysis—to a difference in MTPM between groups of all included patients after 6 years of follow-up, as 6-year data were available at the time of data analysis. To provide unbiased comparisons between groups, the main approach to analyze the results was the intention-to-treat analysis (groups according to allocation). In case of switches between groups so that patients were not treated as randomized, thereby diluting the treatment effect, an as-treated analysis (groups according to received type of prosthesis) was also performed.

The first postoperative radiographs were taken as reference for the migration measurements. We used repeated measures analysis of variance with a linear mixed-effects model to analyze the migration measurements. This is the recommended technique to model repeated measurements as it takes the correlation of measurements performed on the same subject into account and includes all patients in the analysis while dealing effectively with missing values (DeSouza et al. Citation2009, Ranstam et al. Citation2012, Nieuwenhuijse et al. Citation2013). The difference in migration between groups is only tested once after 6-year follow-up to safeguard against multiple testing and is modelled as a function of time and the interaction of time with type of prosthesis (fixed effects). A random-intercepts term is used (random effect) and remaining variability is modelled with a heterogeneous autoregressive order 1 covariance structure. For revised and lost cases, RSA measurements were included in the analysis up to the last follow-up. MTPM was log-transformed during statistical modelling as it was not normally distributed.

The secondary (clinical) outcomes, namely KSS scores, flexion, and extension, were analyzed with a similar linear mixed-effects model. The standard errors of KSS knee score and extension were corrected via the sandwich estimator using a generalized estimating equations approach, as these outcome measures were not normally distributed and a log-transformation did not result in a normal distribution. To illustrate the directions of migration, descriptive data of the translations and rotations along and about the orthogonal axes are presented but not tested for significance.

IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all analyses, and significance was set at p < 0.05.

Ethics, registration, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

The trial was performed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and approved by the local ethics committee prior to enrollment (entry no. P07.205, retrospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02924961). All patients gave informed consent. Reporting of the trial was in accordance with the CONSORT statement. This study was partially funded by a single unrestricted grant from Stryker. The sponsor did not take any part in the design, conduct, analysis, and interpretations stated in the final manuscript.

Results

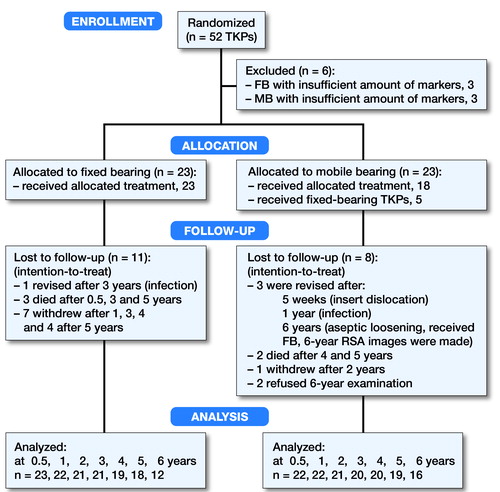

52 knees were eligible in 48 patients (). 6 patients (3 of both groups) were excluded due to an insufficient number of bone markers placed in the proximal tibia, resulting in unmeasurable RSA images. Thus 23 fixed-bearing and 23 mobile-bearing TKPs could be used in the intention-to-treat analysis. During the 6-year follow-up, 5 patients died, 4 revisions were performed (see below), 1 patient withdrew dissatisfied with his knee function, and 9 patients withdrew or refused to visit the clinic for reasons not related to the knee prosthesis. This resulted in 299 valid RSA radiographs used for the migration analysis. Baseline characteristics did not differ between groups ().

Figure 1. CONSORT flow diagram. FB = fixed-bearing, MB = mobile-bearing, TKPs = total knee prostheses.

Table 1. Baseline demographic characteristics. Values are mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated

RSA and clinical outcomes

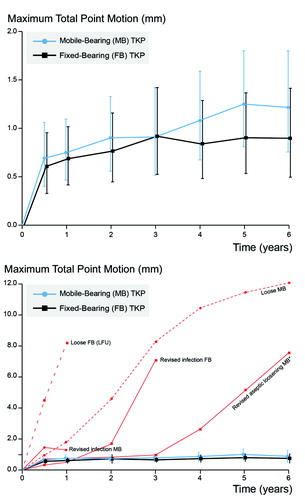

The precision of RSA measurements was assessed with 34 double examinations (). There were no statistically significant differences in mean migration between groups during 6 years of follow-up ( and Table 4, see Supplementary data). Migration remained similar between groups when excluding five components with high migration profiles ().

Figure 2. Mean maximum total point motion and 95% CI for the groups alone (top) and mean and 95% CI for the groups with solid red lines for the revised components and dashed red lines for the components suspected for loosening excluded from the groups (bottom). One component revised due to a mobile-bearing insert dislocation is not shown separately, as this complication occurred before 6 months of follow-up. *Analyzed as mobile-bearing TKP in intention-to-treat analysis but received fixed-bearing TKP. LFU = lost to follow-up.

Table 2. Precision of RSA measurements (upper limits of the 95% CI around zero motion)

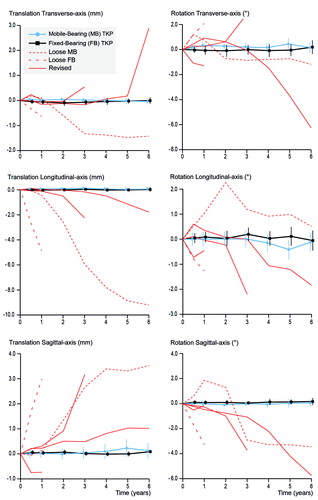

Both groups showed comparable translations and rotations along and around the 3 orthogonal axes, and high migration of individual components was seen in almost any direction (). 5 components showed excessive migration ( and Figure 3), of which 2 were revised for septic loosening (late infections of a mobile-bearing knee with Staphylococcus aureus after 1 year and a fixed-bearing with a Candida albicans after 3 years) and 1 fixed-bearing (randomized in the mobile-bearing group) was revised for aseptic loosening after 6 years (Table 3 #35, see Supplementary data). The other 2 were suspected for aseptic loosening of which 1 mobile-bearing knee was postponed for revision surgery (Figure 4, see Supplementary data) and 1 fixed-bearing, placed in an 81-year-old female with osteoarthritis, was lost to follow-up after 1 year. This patient visited the outpatient clinic after 6 years of follow-up with severe knee complaints, showing a progressive varus alignment of the tibial component (HKA 174° at 1 year versus 168° at the 6-year follow-up), but refused further RSA examinations and treatment (other than a knee brace) due to age and comorbidities. The secondary outcome scores (KSS scores, flexion, and extension) showed no statistical differences in improvement over time between the two groups (Table 5, see Supplementary data).

Figure 3. Descriptive data showing the translations in mm (left side) and rotations in degrees (right side) of the transverse axis (top), longitudinal axis (middle) and sagittal axis (bottom) for both groups (mean and 95% CI). Similar to Figure 2, the revised components (solid red lines) and the 2 components suspected for loosening (dashed red lines) are drawn separately.

Adverse events

Besides the 5 components with excessive migration already stated, 1 patient withdrew due to dissatisfaction. This 47-year-old man with secondary osteoarthritis due to hemophilic arthropathy had a preoperative knee flexion of 85° and a flexion contracture of 15°; postoperatively, his knee flexion did not improve after receiving a fixed-bearing design. 1 mobile-bearing knee was revised due to an insert dislocation, which occurred 5 weeks after surgery (Figure 5, see Supplementary data). Dislocation of a Stryker mobile bearing was not described in the literature at that time and thus necessitated thorough investigations. Patient inclusion was put on hold until the manufacturer had evaluated the reason for this insert dislocation. Incorrect intraoperative mounting of the insert on the tibial post possibly damaged the tibial insert locking mechanism, although the exact cause of the failed locking mechanism remains unclear. For this reason, patient recruitment of this study was stopped preliminarily after 18 out of the intended 20 mobile-bearing TKPs were implanted.

As-treated analysis

Intraoperatively, 1 of the surgeons (who performed 37 of the study procedures) deemed 5 knees unsuitable for the allocated mobile-bearing insert and fixed-bearing components were used instead. The as-treated population therefore included 28 fixed-bearing and 18 mobile-bearing TKPs (see ). The reasons for the deviations and the outcome in these patients are given in Table 3 (see Supplementary data). All primary and secondary outcome results were comparable in the as-treated analysis and subsequently did not alter conclusions (Tables 4–5, see Supplementary data).

Discussion

While migration measured by RSA and clinical outcomes of mobile-bearing and fixed-bearing designs of the single-radius TKP were comparable after 6 years, some of the complications experienced are inherent to the mobile-bearing design. In 5 cases, suboptimal gap balancing during mobile-bearing surgery resulted in the decision to switch to fixed-bearing TKPs, as is recommended in the literature (Bhan and Malhotra Citation2003). Especially if bone resections and soft-tissue releases are performed conservatively in cases with compromised (peri-)articular tissue, insertion of the mobile bearing onto the central post of the baseplate in a perpendicular vertical manner can be technically challenging. Forcing the insert onto the post from a different angle can damage the locking mechanism, which possibly occurred in 1 procedure and, if so, instigated an insert dislocation necessitating revision surgery.

Several explanations have been suggested for the discrepancies between the theoretically expected superior outcome and actual clinical results of mobile-bearing TKPs. First, it is questionable whether the mobile-bearing component truly is mobile in vivo. Garling et al. (Citation2007) performed a fluoroscopic study using a different rotating-platform TKP (NexGen LPS, Zimmer Biomet, Winterthur, Switzerland) and found limited rotation of the mobile bearing. Among other explanations, the authors hypothesized that this might be caused by (1) polyethylene-on-metal impingement due to a mismatch of the location of the fixed pivot point in the rotating-platform design and the actual tibiofemoral rotation point, or (2) due to fibrous tissue formation between the mobile bearing and the baseplate (Garling et al. Citation2007). However, in a previous report on a subset of our study population (Wolterbeek et al. Citation2012), kinematic analysis with step-up and lunge motions showed that overall the mobile-bearing insert followed the femoral component movement as intended by its design, but not in all patients. Second, dislocation of the mobile bearing is a serious complication requiring revision surgery. Historically, this complication was mainly seen in the old mobile meniscal-bearing designs (Namba et al. Citation2011), while insert dislocations in rotating-platform designs are rare nowadays (Huang et al. Citation2002, Thompson et al. Citation2004, Fisher et al. Citation2011). At the time (2008–2010) of patient inclusion for the current study, there were no reports on dislocation of the mobile-bearing insert with similar locking mechanisms as used in the Triathlon TKP. Thus our study was stopped awaiting results of thorough investigations. A case report on a bearing dislocation was later reported, describing failure of the locking O-ring identical to the Triathlon locking mechanism (Kobayashi et al. Citation2011). Testing the mode of failure during revision surgery in our case resulted in similar conclusions: once the O-ring of the insert has been damaged, flexing the knee can lead to lift-off and anterior dislocation of the insert. This was most easily observed while testing the knee intraoperatively with external rotation force. Third, several authors have addressed the effect of surgical procedure volumes, with superior results being attained by high-volume centers (Baker et al. Citation2013, Critchley et al. Citation2012, Lau et al. Citation2012, Liddle et al. Citation2016). Good clinical results reported in single-surgeon series may not be realized in low-volume centers or centers treating patients with diverse demographic factors (Namba et al. Citation2012). In our academic center, all participating surgeons were experienced in performing both mobile-bearing and fixed-bearing total knee arthroplasties and often performed surgery in patients with secondary osteoarthritis due to rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory diseases, which was also the case in a high proportion of the included patients. Nevertheless, the number of adverse events observed in this study was much higher than reported in other clinical (RSA) studies performed in our center. Although this could be due to chance, a learning-curve effect with this new design may have contributed to some of the complications and intraoperative decisions to deviate from the randomized treatment allocation.

A limitation of this study is that patient inclusion was prematurely terminated for patient safety after the mobile-bearing dislocation, before reaching the intended 20 patients in this study arm. This did not compromise the number of patients needed to have sufficient power on the primary outcome in the first 5 years of follow-up, as only 17 patients were required according to the sample size calculation. This was not the case at 6 years (with less than 17 TKPs available for analysis in both groups). However, as the patients lost in the sixth postoperative year had stable migration patterns, it is unlikely that migration at 6 years would substantially differ from the pattern depicted in . Contrarily, results of the clinical outcomes should be interpreted with caution, given the lower accuracy and precision of these measurements. However, large meta-analysis studies comparing mobile-bearing with fixed-bearing TKPs found no differences in clinical outcomes either (van der Voort et al. Citation2013, Hofstede et al. Citation2015). Another limitation is the duration of follow-up. Although early tibial component migration measured through RSA is a proven predictor of late loosening (Ryd et al. Citation1995, Pijls et al. Citation2012b), one can hypothesize about various mechanisms affecting migratory patterns at different time intervals. However, results of an RSA study with long-term follow-up (> 10 years) revealed no changes in migration patterns of mobile-bearing and fixed-bearing prostheses after the first 2 years (Pijls et al. Citation2012a).

In summary, fixed-bearing single-radius TKPs showed similar migration compared with the mobile-bearing TKPs, while the latter may expose patients to more complex surgical techniques and risks such as insert dislocations inherent to this rotating-platform design.

Supplementary data

Tables 3–5 and Figures 4 and 5 and are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2018.1429108

The study was designed by EV and RN. Surgeries were performed by HH, HL, and RN. Data collection and RSA analysis were performed by KH. Statistical analysis was done by KH and PM. KH, PM, EV, and RN interpreted the data and wrote the initial draft manuscript. KH, PM, HH, HL, and RN critically revised and approved the manuscript.

Acta thanks Anders Henricson and Kaj Knutson for help with peer review of this study.

IORT_A_1429108_SUPP.PDF

Download PDF (412.6 KB)- Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Annual Report 2015. Adelaide: AOA; 2015.

- Baker P, Jameson S, Critchley R, Reed M, Gregg P, Deehan D. Center and surgeon volume influence the revision rate following unicondylar knee replacement: an analysis of. 23,400 medial cemented unicondylar knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(8):702–9.

- Bhan S, Malhotra R. Results of rotating-platform, low-contact-stress knee prosthesis. J Arthroplasty 2003; 18(8): 1016–22.

- Buechel F F, Sr. Long-term followup after mobile-bearing total knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002; (404): 40–50.

- Buechel F F, Sr. Mobile-bearing knee arthroplasty: rotation is our salvation! J Arthroplasty 2004; 19(4Suppl1): 27–30.

- Buechel F F, Sr, Buechel F F, Jr, Pappas M J, D’Alessio J. Twenty-year evaluation of meniscal bearing and rotating platform knee replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001; (388): 41–50.

- Callaghan J J, Insall J N, Greenwald A S, Dennis D A, Komistek R D, Murray D W, Bourne R B, Rorabeck C H, Dorr L D. Mobile-bearing knee replacement: concepts and results. Instr Course Lect 2001; 50: 431–49.

- Cho W S, Youm Y S, Ahn S C, Sohn D W. What have we learned from LCS mobile-bearing knee system? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2010; 18(10): 1345–51.

- Critchley R J, Baker P N, Deehan D J. Does surgical volume affect outcome after primary and revision knee arthroplasty? A systematic review of the literature. Knee 2012; 19(5): 513–8.

- DeSouza C M, Legedza A T, Sankoh A J. An overview of practical approaches for handling missing data in clinical trials. J Biopharm Stat 2009; 19(6): 1055–73.

- Fisher D A, Bernasek T L, Puri R D, Burgess M L. Rotating platform spinouts with cruciate-retaining mobile-bearing knees. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26(6): 877–82.

- Garling E H, Kaptein B L, Nelissen R G, Valstar E R. Limited rotation of the mobile-bearing in a rotating platform total knee prosthesis. J Biomech 2007; 40Suppl1: S25–S30.

- Hansson U, Toksvig-Larsen S, Jorn L P, Ryd L. Mobile vs. fixed meniscal bearing in total knee replacement: a randomised radiostereometric study. Knee 2005; 12(6): 414–18.

- Henricson A, Dalen T, Nilsson K G. Mobile bearings do not improve fixation in cemented total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 448: 114–21.

- Hofstede S N, Nouta K A, Jacobs W, van Hooff M L, Wymenga A B, Pijls B G, Nelissen R G, Marang-van de Mheen P J. Mobile bearing vs fixed bearing prostheses for posterior cruciate retaining total knee arthroplasty for postoperative functional status in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 2: CD003130.

- Huang C H, Ma H M, Liau J J, Ho F Y, Cheng C K. Late dislocation of rotating platform in New Jersey Low-Contact Stress knee prosthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002; (405): 189–94.

- ISO 16087:2013(E). Implants for surgery—roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis for the assessment of migration of orthopaedic implants. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization; 2013.

- Jolles B M, Grzesiak A, Eudier A, Dejnabadi H, Voracek C, Pichonnaz C, Aminian K, Martin E. A randomised controlled clinical trial and gait analysis of fixed- and mobile-bearing total knee replacements with a five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012; 94(5): 648–55.

- Kobayashi H, Akamatsu Y, Taki N, Ota H, Mitsugi N, Saito T. Spontaneous dislocation of a mobile-bearing polyethylene insert after posterior-stabilized rotating platform total knee arthroplasty: a case report. Knee 2011; 18(6): 496–8.

- Lau R L, Perruccio A V, Gandhi R, Mahomed N N. The role of surgeon volume on patient outcome in total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012; 13: 250.

- Liddle A D, Pandit H, Judge A, Murray D W. Effect of surgical caseload on revision rate following total and unicompartmental knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2016; 98(1): 1–8.

- Mahoney O M, Kinsey T L, D’Errico T J, Shen J. The John Insall Award: no functional advantage of a mobile bearing posterior stabilized TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012; 470(1): 33–44.

- Molt M, Ljung P, Toksvig-Larsen S. Does a new knee design perform as well as the design it replaces? Bone Joint Res 2012; 1(12): 315–23.

- Namba R S, Inacio MC, Paxton E W, Robertsson O, Graves S E. The role of registry data in the evaluation of mobile-bearing total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011; 93(Suppl3): 48–50.

- Namba R S, Inacio M C, Paxton E W, Ake C F, Wang C, Gross T P, Marinac-Dabic D, Sedrakyan A. Risk of revision for fixed versus mobile-bearing primary total knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94(21): 1929–35.

- Nieuwenhuijse M J, van der Voort P, Kaptein B L, van der Linden-van der Zwaag H M, Valstar E R, Nelissen R G. Fixation of high-flexion total knee prostheses: five-year follow-up results of a four-arm randomized controlled clinical and roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95(19): e1411–11.

- Pagnano M W, Trousdale R T, Stuart M J, Hanssen A D, Jacofsky D J. Rotating platform knees did not improve patellar tracking: a prospective, randomized study of 240 primary total knee arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; (428): 221–7.

- Pijls B G, Valstar E R, Kaptein B L, Nelissen R G. Differences in long-term fixation between mobile-bearing and fixed-bearing knee prostheses at ten to 12 years’ follow-up: a single-blinded randomised controlled radiostereometric trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012a;94(10):1366–71.

- Pijls B G, Valstar E R, Nouta KA, Plevier JW, Fiocco M, Middeldorp S, Nelissen RG. Early migration of tibial components is associated with late revision: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 21,000 knee arthroplasties. Acta Orthop 2012b; 83(6): 614–24.

- Ranstam J, Turkiewicz A, Boonen S, Van Meirhaeghe J, Bastian L, Wardlaw D. Alternative analyses for handling incomplete follow-up in the intention-to-treat analysis: the randomized controlled trial of balloon kyphoplasty versus non-surgical care for vertebral compression fracture (FREE). BMC Med Res Methodol 2012; 12: 35.

- Ryd L, Albrektsson B E, Carlsson L, Dansgard F, Herberts P, Lindstrand A, Regner L, Toksvig-Larsen S. Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis as a predictor of mechanical loosening of knee prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1995; 77(3): 377–83.

- Thompson N W, Wilson D S, Cran G W, Beverland D E, Stiehl J B. Dislocation of the rotating platform after low contact stress total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; (425): 207–11.

- Tjornild M, Soballe K, Hansen P M, Holm C, Stilling M. Mobile- vs. fixed-bearing total knee replacement. Acta Orthop 2015; 86(2): 208–14.

- Valstar E R, Gill R, Ryd L, Flivik G, Borlin N, Karrholm J. Guidelines for standardization of radiostereometry (RSA) of implants. Acta Orthop 2005; 76(4): 563–72.

- van der Voort P, Pijls B G, Nouta K A, Valstar E R, Jacobs W C, Nelissen R G. A systematic review and meta-regression of mobile-bearing versus fixed-bearing total knee replacement in 41 studies. Bone Joint J 2013; 95-B (9): 1209–16.

- Wolterbeek N, Garling E H, Mertens B J, Nelissen R G, Valstar E R. Kinematics and early migration in single-radius mobile- and fixed-bearing total knee prostheses. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2012; 27(4): 398–402.