Abstract

Background and purpose — Larger prospective studies investigating periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) with patient-reported outcome measures developed for young patients are lacking. We investigated changes in patient-reported outcome (PRO), changes in muscle–tendon pain, and any associations between them from before to 1 year after PAO.

Patients and methods — Outcome after PAO was investigated in 82 patients. PRO was investigated with the Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS). Muscle–tendon pain in the hip and groin region was identified with standardized clinical tests, and any associations between them were analyzed with multivariable linear regressions.

Results — HAGOS subscales improved statistically significantly from before to 1 year after PAO with effect sizes ranging from medium to very large (0.66–1.37). Muscle–tendon pain in the hip and groin region showed a large decrease in prevalence from 74% (95% CI 64–83) before PAO to 35% (95% CI 25–47) 1 year after PAO. Statistically significant associations were observed between changes in HAGOS and change in the sum of muscle–tendon pain, ranging from –4.7 (95% CI –8.4 to –1.0) to –8.2 (95% CI –13 to –3.3) HAGOS points per extra painful entity across all subscales from before to 1 year after PAO.

Interpretation — Patients with hip dysplasia experience medium to very large improvements in PRO 1 year after PAO, associated with decreased muscle–tendon pain. The understanding of hip dysplasia as solely a joint disease should be reconsidered since muscle–tendon pain seems to play an important role in relation to the outcome after PAO.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: 20140401PAO.

Traditionally, hip dysplasia is considered a joint disease with insufficient coverage of the femoral head, which is related to early painful degenerative changes (Mechlenburg Citation2008, Ross et al. Citation2011). Pain and physical function can be improved by periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) (Hartig-Andreasen et al. Citation2012, Lerch et al. Citation2017), a well-established surgical treatment of symptomatic hip dysplasia in young patients. We have previously challenged this traditional understanding as we reported a high prevalence of muscle–tendon pain in young patients with hip dysplasia, which negatively affected patient-reported outcome (PRO) (Jacobsen et al. 2018b).

PAO is commonly investigated with patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) developed for older patients with osteoarthritis (Hartig-Andreasen et al. Citation2012, Clohisy et al. Citation2017). In young patients, however, a high score on a PROM designed for older patients does not necessarily indicate an acceptable health status, as more strenuous activities such as sports and recreational activities are not evaluated.

Only a few previous studies have investigated PRO after PAO with PROMs developed for young and physically active patients (Jacobsen et al. Citation2014, Khan et al. Citation2017). In these studies, outcomes were investigated with the Non Arthritic Hip Score (NAHS) and the Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS). The results of the studies showed medium to very large effect sizes. The NAHS, however, was developed for and validated in patients with hip osteoarthritis (Khan et al. Citation2017), while the study using HAGOS was fairly small and focused on objective gait characteristics rather than PRO (Jacobsen et al. Citation2014). Therefore, it is warranted to investigate the outcome of the PAO with PROMs designed for young and active patients, including the possible negative effect of muscle–tendon pain.

We investigated changes in PRO, changes in muscle–tendon pain, and any associations between them from before to 1 year after PAO.

Patients and methods

Patients from the Department of Orthopaedics at Aarhus University Hospital in Denmark were prospectively included from May 2014 to August 2015. They were part of a study population from a previous study (Jacobsen et al. 2018b) and were included if Wiberg’s centre-edge (CE) angle was < 25° (Wiberg Citation1939), if they had had groin pain for at least 3 months, and if they were scheduled for PAO. Furthermore, only patients < 45 years, with BMI < 30, normal range of motion (minimum 110° of hip flexion), and with Tönnis’s osteoarthritis grade < 2 (Tönnis Citation1987) were operated on. Patients with comorbidities and previous surgical interventions affecting their hip function were excluded. Further details on study design are reported in our previous studies on the same study population, reporting prevalence of muscle–tendon pain and structural abnormalities before PAO (Jacobsen et al. Citation2018a, Citation2018b).

Before PAO, patient characteristics including age, sex, and duration of pain were recorded based on standardized questions. A single rater measured the CE angle, the Tönnis acetabular index (AI) angle (Tönnis Citation1987), and the Tönnis osteoarthritis grade on standing anteroposterior radiographs. Information on comorbidities and previous treatments was extracted from hospitals charts. Pain was recorded using the FABER (Flexion/Abduction/External Rotation) test and the FADDIR (Flexion/Adduction/Internal Rotation) test (Troelsen et al. Citation2009, Martin et al. Citation2010). Additionally, a standardized test was used to record occurrence of internal snapping hip (Tibor and Sekiya Citation2008).

Periacetabular osteotomy

The minimally invasive transsartorial approach for PAO was performed by 2 experienced orthopedic surgeons via 3 separate osteotomies (Troelsen et al. Citation2008). In short, an approximately 7 cm incision was made alongside the sartorius muscle beginning at the anterior superior iliac spine. The sartorius muscle was divided parallel with the direction of its fibers. The medial part of the split muscle was retracted medially together with the iliopsoas muscle, and this was followed by osteotomies. The patients were presented with a standardized post-surgery rehabilitation program on the ward, and discharged after approximately 2 days of hospitalization. Partial weight-bearing was allowed in the first 6–8 weeks. Moreover, all patients were offered an individual-based rehabilitation program of 2 weekly training sessions starting 6 weeks after PAO and lasting generally for 2–4 months.

Patient-reported outcome measure

The HAGOS was completed before and 1 year after PAO by all patients prior to assessment of muscle–tendon pain. HAGOS consists of 6 separate subscales covering pain, symptoms, physical function in daily living (ADL), physical function in sports and recreation (sports/recreation), participation restriction (PA), and quality of life (QOL) (Thorborg et al. Citation2011). HAGOS is tailored to reflect physically active young and middle-aged patients with long-standing hip and/or groin pain. HAGOS measures the patient’s hip-related disability during the past week on a scale from 0 to 100 points, where 100 points indicates best possible outcome.

Pain at rest was measured before and 1 year after PAO on a numeric rating scale (NRS) from 0 (no pain) to 10 (unbearable pain).

Muscle–tendon pain

We assessed muscle–tendon pain before and 1 year after PAO with standardized clinical examinations originally proposed by Hölmich et al. (Citation2004) and modified by the Doha consensus statement (Weir et al. Citation2015). The standardized examination covers a number of pain-provoking tests including anatomical palpation, resistance testing, and passive muscle stretch in specific anatomical regions, named clinical entities (Weir et al. Citation2015). In our study, we added identification of pain in the hamstrings and abductors following the same principle as the other clinical entities, since these structures were considered important in our study. Moreover, pain related to the rectus abdominis (Hölmich et al. Citation2004) was the focus in this study as an alternative to inguinal-related pain defined in the Doha consensus since most patients were women. Muscle–tendon pain was assessed in 5 anatomical entities: the iliopsoas, the abductors, the adductors, the hamstrings, and the rectus abdominis. Muscle–tendon pain was investigated within each entity and as the sum of positive clinical entities for each patient, ranging from 0 to 5. The outcome of each entity test was dichotomous (pain yes or no).

Sample size considerations

The aim of this study was to investigate 1-year outcome of the PAO using HAGOS. Moderate effect sizes were considered relevant, which would require a sample size of 85 patients to show an effect size of 0.5 from before to 1 year after PAO. This sample size is based on a power of 90% and a significance level of 5%.

Statistics

Parametric continuous data were reported as means with standard deviations (SD) if normally distributed, otherwise reported as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). Histograms and probability plots were used to test for normality. Categorical data were reported as numbers of events and percentage with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Changes in each HAGOS subscale measured before and 1 year after PAO were considered important and were tested with paired t-tests. Similarly, changes in each muscle–tendon pain entity from before to 1 year after PAO were considered equally important. These were tested with the McNemar test. Effect sizes of HAGOS and muscle–tendon pain were calculated from the paired t-test as Cohen’s d on the formula: t statistic/√(n), and from McNemar test as Cohen’s w on the formula: w statistic/√(n). Finally, crude and adjusted multivariable linear regression analyses were performed to assess associations between changes in HAGOS (pain, symptoms, ADL, sport/recreation, PA, and QOL) and change in the sum of muscle–tendon pain entities (i.e., the sum of positive clinical entities for each patient) from before to 1 year after PAO. Changes in each HAGOS subscale were the dependent variables, and the sum of muscle–tendon pain entities for each patient was the independent variable. Potential co-variates were identified using causal diagrams for observational research, based on knowledge from previous studies (Greenland et al. Citation1999). Co-variates included in the analysis were CE angles measured before and 1 year after PAO (continuous), age (continuous), and sex (dichotomous). Crude and adjusted β-coefficients were estimated and the assumptions (independent observations, linear association, constant variance of residuals, and normal distribution of residuals) of the regression models were met. The β-coefficients refer to the slope of the regression line, indicating a decrease in changed PRO per unit increase in muscle–tendon pain. The STATA 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) software package was used for data analysis, and results were considered statistically significant if p < 0.05.

Ethics, registration, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

This study was conducted and reported in accordance with the WMA declaration of Helsinki and the STROBE statement. All patients gave informed consent to participate, and ethical approval was obtained from the Central Denmark Region Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics (5/2014). The Danish Data Protection Agency (1-16-02-47-14) authorized the handling of personal data, and the protocol was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (20140401PAO). This study was funded by the Danish Rheumatism Association, the Aase and Ejnar Danielsen Fund, and the Fund of Family Kjaersgaard, Sunds. The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Results

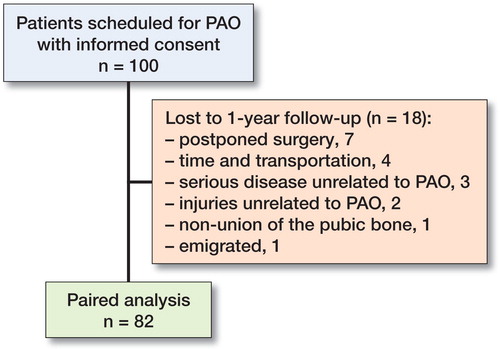

Informed consent was obtained from 100 consecutive patients before PAO. 18 patients were lost to follow-up (Figure), leaving 82 patients for this study (). We found no statistically significant differences in any of the listed patient characteristics between the 18 patients lost to follow-up and the analyzed patients (data not shown).

Table 1. Characteristics of 82 consecutive patients with hip dysplasia

Patient-reported outcome

We found statistically significant increases in all HAGOS subscales from before to 1 year after PAO (). The effect sizes ranged from 0.66 to 1.37, corresponding to medium to very large effect sizes. Moreover, 26/82 patients reported a sport/recreation score of 0–50 points 1 year after PAO, 14/82 patients reported a sport/recreation score of >50–70 points, while 42/82 patients reported a sport/recreation score >70 points 1 year after PAO. Similarly, NRS pain decreased statistically significantly, corresponding to a medium effect size of 0.74.

Table 2. Patient-reported outcome of PAO in 82 patients with hip dysplasia

Muscle–tendon pain

The analysis of the individual entities showed a significant decrease in iliopsoas-related pain and abductor-related pain from before to 1 year after PAO, whereas the decrease in the other 3 entities was not statistically significant (). Moreover, the proportion of patients with minimum 1 positive muscle–tendon pain entity decreased by 39 percentage points (CI 24–54) 1 year after PAO.

Table 3. Muscle–tendon pain in 82 patients with hip dysplasia

Associations between changes in HAGOS and change in muscle–tendon pain

Apart from HAGOS PA, both crude and adjusted analyses showed statistically significant negative linear association between changes in HAGOS and change in the sum of muscle–tendon pain entities, ranging from –4.7 to –8.2 HAGOS points per extra painful entity across all subscales from before to 1 year after PAO ().

Table 4. Associations between change in HAGOS (0–100 points) and change in muscle–tendon pain (n = 82)

Discussion

We investigated changes in PRO, changes in muscle–tendon pain, and any associations between them from before to 1 year after PAO. Our patients reported clinically relevant improvements in all HAGOS subscales with effect sizes ranging from medium to very large. All improvements were higher than the minimally important change (MIC) of the HAGOS (Thomeé et al. Citation2014). Nevertheless, 1 year after PAO, one-third of the patients still experienced muscle–tendon pain, most commonly affecting the iliopsoas and the hip abductors. Furthermore, our regression analyses showed that change in the sum of muscle–tendon pain was associated with changes in PRO of the PAO.

Only 2 previous studies have investigated the outcome of PAO with PROMs tailored to reflect activity levels of young and active patients. Jacobsen et al. (Citation2014) reported PRO after PAO, applying HAGOS, and found medium to very large improvements corresponding to effect sizes from 0.78 to 1.75 in a study population of 29 patients with hip dysplasia. Similarly, a consecutive study on 168 patients with hip dysplasia reported very large patient-reported improvement corresponding to an effect size of 1.5 measured with the NAHS (Khan et al. Citation2017). The HAGOS subscale scores, we found, ranged from 44 to 81 points, which is in accordance with the study by Jacobsen et al. (Citation2014), reporting scores of 50 to 90 HAGOS points 1 year after PAO in another series of patients. The association between change in HAGOS PA and change in the sum of muscle–tendon pain entities was not statistically significant. However, the lack of association between change in HAGOS PA and change in muscle–tendon pain can be explained since HAGOS PA measures patients’ self-perceived ability to participate in a preferred physical activity (Thorborg et al. Citation2011), which is not related to specific functions and activities like the other HAGOS subscales. Therefore, it is not surprising that perceived participatory capacity is not reflected in change in muscle–tendon pain and vice versa.

We did not include a healthy control group; however, an age- and sex-matched healthy control group was included in a previous study, investigating the outcome 1 year after PAO using HAGOS (Jacobsen et al. Citation2014). All healthy subjects reported a PRO of 84–100 HAGOS sport/recreation points, which was different from the HAGOS sport/recreation score measured 1 year after PAO in the patients with hip dysplasia (Jacobsen et al. Citation2014). In this study, half of the patients reported a HAGOS score ≤ 70 sport/recreation points 1 year after PAO. This indicates that patients still experience a low functional level, associated with muscle–tendon pain.

Our patients showed a clinically relevant reduction in pain related to the iliopsoas and the hip abductors. This decrease may be a result of both surgical reorientation and the intensive individual-based rehabilitation program. The effect of muscle–tendon pain on changes in HAGOS score was 5–8 HAGOS points for every change in number of painful clinical entities across all HAGOS subscales, which is in line with the MIC of HAGOS (Thomeé et al. Citation2014). This suggests that resolving just 1 painful clinical entity after PAO has a clinically relevant impact on the outcome 1 year after PAO.

Muscle–tendon affection in patients with hip dysplasia has only been reported in 1 previous study, which reported muscle–tendon affection among one-fifth of the patients identified by hip arthroscopy (Domb et al. Citation2014). However, associations between muscle–tendon affection and patient-reported outcomes were not investigated.

Methodological considerations and limitations

As reported in our previous study on the same study population, we found low inter-rater reliability of the muscle–tendon pain assessment, indicating a high random variation in our estimates (Jacobsen et al. 2018b). The potentially negative impact of this is small because we included a large study population. The associations between changes in HAGOS and change in the sum of muscle–tendon pain were mainly driven by patients who either reduced many painful entities or increased the number of painful entities 1 year after PAO. The same analysis without these patients would have resulted in smaller associations or even lack of significant associations between HAGOS and muscle–tendon pain.

Summary

Patients with hip dysplasia experience medium to very large improvements in PRO 1 year after PAO, associated with decreased muscle–tendon pain. The understanding of hip dysplasia as solely a joint disease should be reconsidered as muscle–tendon pain seems to play an important role in relation to the outcome after PAO. Future intervention studies ought to investigate the optimal treatment for patients with hip dysplasia and coexisting muscle–tendon pain.

All authors were involved in the planning and writing of the manuscript. IM, KT, PH, and LB gave supervision on design and methods. KS and SSJ included and operated on all patients. JSJ examined patients, while SSJ made all radiologic evaluations. JSJ coordinated all elements, wrote the first description of the study, did all analyses, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

The authors would like to thank Charlotte Møller Sørensen and Gitte Hjørnholm Madsen for their invaluable assistance carrying out the clinical examinations.

Acta thanks Minne Heeg and Yvette Pronk for help with peer review of this study.

- Clohisy J C, Ackerman J, Baca G, Baty J, Beaulé P E, Kim Y-J, Millis M B, Podeszwa D A, Schoenecker P L, Sierra R J, Sink E L, Sucato D J, Trousdale R T, Zaltz I. Patient-reported outcomes of periacetabular osteotomy from the prospective ANCHOR cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017; 99(1): 33–41.

- Domb B G, Lareau J M, Baydoun H, Botser I, Millis M B, Yen Y-M. Is intraarticular pathology common in patients with hip dysplasia undergoing periacetabular osteotomy? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472(2): 674–80.

- Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins J M. Causal diagrams for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology 1999; 10(1): 37–48.

- Hartig-Andreasen C, Troelsen A, Thillemann T M, Søballe K. What factors predict failure 4 to 12 years after periacetabular osteotomy? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012; 470(11): 2978–87.

- Hölmich P, Hölmich L R, Bjerg A M. Clinical examination of athletes with groin pain: an intraobserver and interobserver reliability study. Br J Sports Med 2004; 38(4): 446–51.

- Jacobsen J S, Bolvig L, Hölmich P, Thorborg K, Jakobsen S S, Søballe K, Mechlenburg I. Muscle–tendon-related abnormalities detected by ultrasonography are common in symptomatic hip dysplasia. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2018a; 138(8): 1059–67.

- Jacobsen J S, Hölmich P, Thorborg K, Bolvig L, Jakobsen S S, Søballe K, Mechlenburg I. Muscle–tendon-related pain in 100 patients with hip dysplasia: prevalence and associations with self-reported hip disability and muscle strength. J Hip Preserv Surg 2018b; 5(1): 39–46.

- Jacobsen J S, Nielsen D B, Sørensen H, Søballe K, Mechlenburg I. Joint kinematics and kinetics during walking and running in 32 patients with hip dysplasia 1 year after periacetabular osteotomy. Acta Orthop 2014; 85(6): 592–9.

- Khan O H, Malviya A, Subramanian P, Agolley D, Witt J D. Minimally invasive periacetabular osteotomy using a modified Smith–Petersen approach. Bone Joint J 2017; 99-B(1): 22–8.

- Lerch T D, Steppacher S D, Liechti E F, Tannast M, Siebenrock K A. One-third of hips after periacetabular osteotomy survive 30 years with good clinical results, no progression of arthritis, or conversion to THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017; 475(4): 1154–68.

- Martin H D, Kelly B T, Leunig M, Philippon M J, Clohisy J C, Martin R L, Sekiya J K, Pietrobon R, Mohtadi N G, Sampson T G, Safran M R. The pattern and technique in the clinical evaluation of the adult hip: the common physical examination tests of hip specialists. Arthroscopy 2010; 26(2): 161–72.

- Mechlenburg I. Evaluation of Bernese periacetabular osteotomy. Acta Orthop 2008; 79(Suppl 329): 1–43.

- Ross J R, Zaltz I, Nepple J J, Schoenecker P L, Clohisy J C. Arthroscopic disease classification and interventions as an adjunct in the treatment of acetabular dysplasia. Am J Sports Med 2011; 39(Suppl): 72S-8S.

- Thomeé R, Jónasson P, Thorborg K, Sansone M, Ahldén M, Thomeé C, Karlsson J, Baranto A. Cross-cultural adaptation to Swedish and validation of the Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS) for pain, symptoms and physical function in patients with hip and groin disability due to femoro-acetabular impingement. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014; 22(4): 835–42.

- Thorborg K, Hölmich P, Christensen R, Petersen J, Roos E M. The Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS): development and validation according to the COSMIN checklist. Br J Sports Med 2011; 45(6): 478–91.

- Tibor L M, Sekiya J K. Differential diagnosis of pain around the hip joint. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg 2008; 24(12): 1407–21.

- Tönnis D. Congenital dysplasia and dislocation of the hip in children and adults. Berlin Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 1987.

- Troelsen A, Elmengaard B, Søballe K. A new minimally invasive transsartorial approach for periacetabular osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008; 90(3): 493–8.

- Troelsen A, Mechlenburg I, Gelineck J, Bolvig L, Jacobsen S, Søballe K. What is the role of clinical tests and ultrasound in acetabular labral tear diagnostics? Acta Orthop 2009; 80(3): 314–8.

- Weir A, Brukner P, Delahunt E, Ekstrand J, Griffin D, Khan K M, Lovell G, Meyers W C, Muschaweck U, Robinson P, De Vos R-J, Vuckovic Z. Doha agreement meeting on terminology and definitions in groin pain in athletes. Br J Sport Med 2015; 49: 768–74.

- Wiberg G. Studies on dysplastic acetabula and congenital subluxation of the hip joint. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 1939; 58: 1–132.