Abstract

Background and purpose — While the number of working-age patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty (THA) is increasing, the effect of the surgery on patients’ return to work (RTW) is not thoroughly studied. We aimed to identify risk factors of RTW after THA among factors related to demographic variables, general health, health risk behaviors, and socioeconomic status.

Patients and methods — We studied 408 employees from the Finnish Public Sector (FPS) cohort (mean age 54 years, 73% women) who underwent THA. Information on demographic and socioeconomic variables, preceding health, and health-risk behaviors was derived from linkage to national health registers and FPS surveys before the operation. The likelihood of return to work was examined using Cox proportional hazard modeling.

Results — 94% of the patients returned to work after THA on average after 3 months (10 days to 1 year) of sickness absence. The observed risk factors of successful return to work were: having < 30 sick leave days during the last year (HR 1.8; 95% CI 1.4–2.3); higher occupational position (HR 2.2; CI 1.6–2.9); and BMI < 30 (HR 1.4; CI 1.1–1.7). Age, sex, preceding health status, and health-risk behaviors were not correlated with RTW after the surgery.

Interpretation — Most employees return to work after total hip arthroplasty. Obese manual workers with prolonged sick leave before the total hip replacement were at increased risk of not returning to work after the surgery.

Given the need for a longer working career and patients’ expectations of improved mobility after the surgery, the return to work (RTW) has been suggested to be an important marker of surgery success (Kuijer et al. Citation2009, Malviya et al. Citation2014, Tilbury et al. Citation2014). The RTW has positive effects on patients’ physical and mental health and social and economic benefits if employed (Liang et al. Citation1986, Koenig et al. Citation2016). Of the patients who undergo THA, 68% to 95% return to work (Mobasheri et al. Citation2006, Bohm Citation2010, Nunley et al. Citation2011, Tilbury et al. Citation2014, Hoorntje et al. Citation2018). Due to a growing number of annual procedures, however, a substantial number of patients are not able to continue working after THA.

We aimed to identify risk factors of unsuccessful RTW after THA among factors related to demographic variables, general health, health-risk behaviors, and socioeconomic status in a large nationwide cohort of public sector employees.

Patients and methods

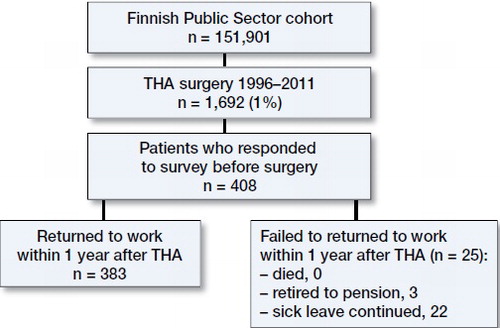

The patients were identified from the Finnish Public Sector (FPS) study, a nationwide register- and survey-based cohort amongst employees of 10 municipalities and 6 hospital districts covering a wide range of occupations—from city mayors and doctors to semiskilled cleaners, nurses, and teachers (Airaksinen et al. 2017). The cohort members had been employed for a minimum of 6 months in the participating organizations between 1991 and 2005 (n = 151,901) (). Since 1997, repeated questionnaire data with approximately 4-year intervals have been collected from all employees at work at the time of the survey. The information on baseline characteristics before the surgery was derived from the survey responses, the employers’ records, and national health registers. All participants have been linked to surgical data on THA from the National Care Register for Health Care, maintained by the National Institute for Health and Welfare, as well as the National Sickness Absence Register maintained by the Social Insurance Institution of Finland. The linkage data were available until December 31, 2011.

Type of surgery and patient characteristics

Of the FPS cohort members, 1,690 underwent a unilateral THA between 1999 and 2011 (). Of these, 408 had responded to a survey before the surgery and were included in the study. THA was performed in patients mainly because of primary hip osteoarthritis (n = 369, 90%). Risk factors were measured on average 3.6 years (SD 1.9, range 1.0–9.9) before the operation. The type of surgery was defined as NFB30, NFB40, NFB50, NFB60, NFB62, or NFB99 according to the NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures Version 1.14 by the Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee.

Return to work (RTW)

RTW was determined as the number of days between the date of discharge and the date of the end of the sick leave. Return to work was defined here both as full and part time. All Finnish residents aged 16 to 67 years are legitimized to receive daily allowances due to medically certified sickness absence. All sickness absence periods are medically certified, and they are encoded in the register with start and end dates. The RTW was also dichotomized as yes vs. no.

Risk factors of RTW

The participants’ demographic variables (sex, age) and occupational grade at the time of the surgery were obtained from the employers’ registers. The spectrum of occupational grades was coded according to the International Standard Classification of Occupation (ISCO) and then downsized to 3 groups: higher-grade non-manual workers (e.g., teachers, physicians), lower-grade non-manual workers (e.g., registered nurses, technicians), and manual workers (e.g., cleaners, maintenance workers). Marital status (married or cohabiting vs. single, divorced, or widowed) was obtained from a baseline questionnaire. Age was defined in full years at the time of THA.

Information on health and health behaviors was obtained from the baseline questionnaire and national health registers. Physical activity was defined as average weekly hours of leisure-time physical activity (walking, brisk walking, jogging, and running, or similar), including commuting, during the previous year (Kujala et al. Citation1998). The hours per week spent on activity at each intensity level were multiplied by the average energy expenditure of each activity expressed in metabolic equivalent of task (MET). Physical activity was categorized into 2 groups, “low” (≤ 14 MET-hours/week) and “high” activity (> 14 MET-hours/week). Alcohol consumption was categorized according to the habitual frequencies of drinking beer, wine, and spirits as “none”, “moderate,” and “heavy” consumption. The cut-off for heavy alcohol consumption was set as 210 g/week (Rimm et al. Citation1999). Smoking status was dichotomized as “currently smoking” vs. “quit or never smoked.” Self-reported body weight and height were used to calculate BMI, which was used to identify obese (BMI ≥ 30) and non-obese (BMI < 30) participants. Psychological distress was measured with the 12-item version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) (Goldberg et al. Citation1997) with 3 or more positive response set as a cut-off point of psychological distress (“yes” vs. “no”). Participant rated their general health on a 5-point scale (from 1 = “good health” to 5 = “worst health”), and the self-rated health was then dichotomized by categorizing response scores 1 and 2 as good and scores 3 to 5 as poor general health. The data on the presence of diabetes, coronary heart disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or rheumatoid arthritis were obtained from the Drug Reimbursement Register, which contains information on persons entitled to special reimbursement for treatment of chronic health conditions. The presence of comorbidity was then dichotomized as “yes” vs. “no.”

Statistics

The participants were followed from the date of discharge to the date when an employee returned to work, was granted a disability pension, an old-age pension, died, or end of study (December 31, 2011), whichever came first.

Cox proportional hazard models were used to study the associations between baseline characteristics and return to work. We examined the associations separately for each risk factor adjusted for age and sex. The results are presented as hazard ratios (HR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Proportional hazards assumption of the Cox model was fulfilled concerning all other parameters studied, except socioeconomic status, alcohol consumption, and perceived general health. For these 3 parameters, Schemper’s weighted Cox regression was used (Schemper et al. Citation2009).

All analyses were performed using the SAS statistical software, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

The ethics committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa approved the study (ethical approval: 22.3.2011, Dnor 60/13/03/00/2011). All investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research. MK received a grant from the Academy of Finland (311492) for the conduct of the study. No competing interests were declared.

Results

The majority, 73% of patients, were women (Table). The occupational status was evenly distributed among the 3 groups. The average age at the time of surgery was 54 years (32–67). 15% of patients had some chronic medical comorbidity and 53% reported good general health (Table).

Risk factors of RTW

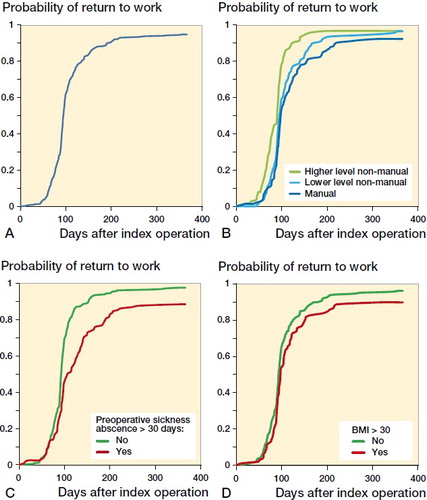

After the surgery, 94% (n = 383) of the patients returned to work after a mean of 103 days (10–354) of sickness absence (). Of the prognostic variables examined, occupational status, sickness absences before the operation, and obesity were statistically significantly associated with RTW. Patients with higher non-manual occupational status had a 2.2 (CI 1.6–2.9) times higher probability of RTW than manual workers adjusted for age and sex (Table). Low compared with high number of sick leaves (< 30 days) before the surgery was associated with a 1.8 (CI 1.4–2.3) times higher probability of RTW. Also, non-obese patients were more likely to return to work than obese patients (HR 1.4 (CI 1.1–1.7).

Figure 2. Probability of return to work overall (A), or according to occupational status (B), preoperative sickness absence (C), and obesity (D). The expected dispersion of survival curves between categories of these patient characteristics was observed across the entire follow-up period (log-rank test: p < 0.001 for occupational status and sickness absences, p = 0.01 for obesity).

Baseline characteristics of the patients and their associations with the rate of return to work after THA. Hazard ratios (HR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) are derived from Cox proportional hazard analyses. Schemper’s weighted Cox regression was used concerning occupational status, alcohol consumption and self-related health because proportional hazards assumption was not fulfilled

illustrates the RTW curves by occupational status, sickness absences before the operation, and obesity. The expected dispersion of curves between categories of these patient characteristics was observed across the entire follow-up period (log-rank test: p < 0.001 for occupational status and sickness absences, p = 0.01 for obesity).

Demographic variables (age and sex), from socioeconomic factors marital status, health behaviors (smoking, physical activity, and high alcohol consumption), chronic medical comorbidities (asthma, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, and coronary artery disease), or psychological distress were not statistically significantly associated with RTW (Table).

Discussion

Successful return to work has been identified as a crucial outcome marker for patients after THA (Kuijer et al. Citation2009, Malviya et al. Citation2014, Tilbury et al. Citation2014). Larger patient series are needed to assess the principal factors for successful return to work and to evaluate the interaction of these factors using multivariate analysis.

Our findings are in line with previous studies. Stigmar et al. (Citation2017) reported that, for Swedish patients who started a sick leave period from day 7 before surgery and who had had no ongoing sick leave from day 30 to day 8 prior to THA surgery, the median postoperative sick leave period for women and men was similar, 3 months. In our study, for patients who did not have > 30 days’ sickness absence within the 1-year period preceding the operation the median postoperative sick leave was similar. The employment status and sick leaves before the surgery have been suggested to be important determinants of returning to work after hip replacement (Jensen et al. Citation1985, Johnsson and Persson Citation1986, Mobasheri et al. Citation2006, Bohm Citation2010, Cowie et al. Citation2013). Bohm (Citation2010) did not observe a correlation between RTW and sex, smoking status, or high alcohol consumption. Lower socioeconomic statuses have been reported to be associated with a higher incidence of osteoarthritis and a higher disability level (Thumboo et al. Citation2002, Wetterholm et al. Citation2016). In a Swedish cohort study, osteoarthritis was diagnosed earlier and the incidence rate of hip replacement surgery was higher among patients with higher income and higher educational level (Wetterholm et al. Citation2016). While some previous studies have produced conflicting evidence on the influence of obesity on THA outcome (Moran et al. Citation2005, Namba et al. Citation2005, Davis et al. Citation2011, Alvi et al. Citation2015), others have reported that obesity might also affect RTW (Cowie et al. Citation2013).

Identifying factors predicting RTW after THA may help in patient selection and setting adequate goals for medical and occupational rehabilitation after the surgery. Numerous factors have been suggested as potential risk factors of unsuccessful RTW after THA: health behaviors, age, educational level, comorbidities, surgical complications, and type of work, as well as the length of sick leaves before the surgery (Nevitt et al. Citation1984, Jensen et al. Citation1985, Johnsson and Persson Citation1986, Suarez et al. Citation1996, Mobasheri et al. Citation2006, Kuijer et al. Citation2009, Nunley et al. Citation2011, Cowie et al. Citation2013, Malviya et al. Citation2014, Tilbury et al. Citation2014, Leichtenberg et al. Citation2016, Hoorntje et al. Citation2018). Previous studies in this field of research have mostly been conducted on relatively small samples exploiting separately either register-based data or data obtained from surveys and, in most cases, risk factors have been measured close to the time of surgery, blocking out the long-term effects of risks (Kuijer et al. Citation2009, Nunley et al. Citation2011, Malviya et al. Citation2014, Tilbury et al. Citation2014, Kleim et al. Citation2015, Bardgett et al. Citation2016a). The relative importance of the multiple risk factors of not returning to work has therefore remained unclear.

In relation to socioeconomic status and preoperative sick leave, our findings were in line with the conclusions of 3 previous systematic reviews and 1 meta-analysis on the subject (Kuijer et al. Citation2009, Malviya et al. Citation2014, Tilbury et al. Citation2014, Hoorntje et al. Citation2018). Contrary to findings of these reviews, we did not find any effect of age on RTW. In relatively young patients (mean age 50 years) Nunley et al. (Citation2011) reported that younger age, physical activity, and employment at the time of surgery were associated with RTW. Cowie et al. (Citation2013), Jensen et al. (Citation1985), and Bohm (2010) have also reported on a correlation between RTW and age, physical condition, and comorbidities. Workplace conditions have also been found to be associated with work performance after the THA (Kuijer et al. Citation2009, Malviya et al. Citation2014, Tilbury et al. Citation2014).

The reasons for differences between our results and earlier reports may lie in the diversities in studied samples that are, especially when insurance issues are involved, bounded to national health care and insurance systems.

Strengths and weaknesses

Compared with previous literature, our study has notable strengths. The cohort size was large enough to employ sophisticated statistical methods. The studied sample came from a well-characterized occupational cohort and represented a wide range of occupations. The comprehensive data have been gathered on health and health-risk behaviors before the surgery. All the data were linked to reliable national health registers including detailed information on objective data on the date of the operation and the beginning and end dates of all periods of sickness absence and comorbidities, enabling accurate estimation of the timing of return to work. Many risk factors of unsuccessful RTW, such as occupational status, sickness absences before the operation, and comorbid medical conditions, were measured objectively from the registers.

The generalizability of these findings may be affected by the differences in national welfare, pension, and workers’ compensation schemes (Scott et al. Citation2017). The studied cohort was limited to employees in the public sector and dominated by women. No data on workplace adjustments before or after the surgery were available. The motivation for RTW, which is always a potential source of uncertainty in studies on such a subject, remains unknown. No data on possible complications and revision surgery were available. Prosthetic joint infections, periprosthetic fractures, or dislocations may remarkably influence the RTW. Another limitation is that we were not able to assess patients’ activity levels, patient-reported THA satisfaction, or functional outcome scores. The RTW may also be influenced by patients’ interactions with healthcare professionals as well as patients’ pre-surgery expectations (Bardgett et al. Citation2016b), which were not known.

In summary, more than 9 out of 10 working-aged patients returned to work after THA. Obese manual workers with prolonged sick leave before the total hip replacement were at increased risk of not returning to work after the surgery. These risk factors should be accounted for when planning THA and post-surgery rehabilitation. All the other studied socioeconomic factors were not associated with the return to work rate. Orthopedic surgeons should consider referring patients at risk for no RTW for additional work-directed care.

RL, PL, KM, and JV designed the study. RL, PL, VA, MK, KM, and JV carried out the analytical aspects of the study, including statistical analysis and modeling. RL, PL, MS, KM, and JV drafted the manuscript. KM and JV contributed equally to the study, and are joint senior authors.

Acta thanks Martin Englund and Paul Kuijer for help with peer review of this study.

- Airaksinen J, Jokela M, Virtanen M, Oksanen T, Pentti J, Vahtera J, Koskenvuo M, Kawachi I, Batty G D, Kivimaki M. Development and validation of a risk prediction model for work disability: multicohort study. Sci Rep 2017; 7(1): 13578.

- Alvi H M, Mednick R E, Krishnan V, Kwasny M J, Beal M D, Manning D W. The effect of BMI on 30 day outcomes following total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2015; 30(7): 1113–17.

- Bardgett M, Lally J, Malviya A, Kleim B, Deehan D. Patient-reported factors influencing return to work after joint replacement. Occup Med (Lond) 2016a; 66(3): 215–21.

- Bardgett M, Lally J, Malviya A, Deehan D. Return to work after knee replacement: a qualitative study of patient experiences. BMJ Open 2016b; 6(2): e007912,2015-007912.

- Bohm E R. The effect of total hip arthroplasty on employment. J Arthroplasty 2010; 25(1): 15–18.

- Cowie J G, Turnbull G S, Ker A M, Breusch S J. Return to work and sports after total hip replacement. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2013; 133(5): 695–700.

- Davis A M, Wood A M, Keenan A C, Brenkel I J, Ballantyne J A. Does body mass index affect clinical outcome post-operatively and at five years after primary unilateral total hip replacement performed for osteoarthritis? A multivariate analysis of prospective data. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93(9): 1178–82.

- Finnish Arthroplasty Register (FAR). http://www.thl.fi/far

- Goldberg D P, Gater R, Sartorius N, Ustun T B, Piccinelli M, Gureje O, Rutter C. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med 1997; 27(1): 191–7.

- Hoorntje A, Janssen K Y, Bolder S B T, Koenraadt K L M, Daams J G, Blankevoort L, Kerkhoffs G M M J, Kuijer P P F M. The effect of total hip arthroplasty on sports and work participation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 2018; 48(7): 1695–726.

- Jensen J S, Mathiesen B, Tvede N. Occupational capacity after hip replacement. Acta Orthop Scand 1985; 56(2): 135–7.

- Johnsson R, Persson B M. Occupation after hip replacement for arthrosis. Acta Orthop Scand 1986; 57(3): 197–200.

- Kleim B D, Malviya A, Rushton S, Bardgett M, Deehan D J. Understanding the patient-reported factors determining time taken to return to work after hip and knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015; 23(12): 3646–52.

- Koenig L, Zhang Q, Austin M S, Demiralp B, Fehring T K, Feng C, Mather R C, 3rd, Nguyen J T, Saavoss A, Springer B D, Yates A J, Jr. Estimating the societal benefits of THA after accounting for work status and productivity: a Markov model approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2016; 474(12): 2645–54.

- Kuijer P P, de Beer M J, Houdijk J H, Frings-Dresen M H. Beneficial and limiting factors affecting return to work after total knee and hip arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil 2009; 19(4): 375–81.

- Kujala U M, Kaprio J, Sarna S, Koskenvuo M. Relationship of leisure-time physical activity and mortality: the Finnish twin cohort. JAMA 1998; 279(6): 440–4.

- Leichtenberg C S, Tilbury C, Kuijer P, Verdegaal S, Wolterbeek R, Nelissen R, Frings-Dresen M, Vliet Vlieland T. Determinants of return to work 12 months after total hip and knee arthroplasty. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2016; 98(6): 387–95.

- Liang M H, Cullen K E, Larson M G, Thompson M S, Schwartz J A, Fossel A H, Roberts W N, Sledge C B. Cost-effectiveness of total joint arthroplasty in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1986; 29(8): 937–43.

- Malviya A, Wilson G, Kleim B, Kurtz S M, Deehan D. Factors influencing return to work after hip and knee replacement. Occup Med (Lond) 2014; 64(6): 402–9.

- Mobasheri R, Gidwani S, Rosson J W. The effect of total hip replacement on the employment status of patients under the age of 60 years. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2006; 88(2): 131–3.

- Moran M, Walmsley P, Gray A, Brenkel I J. Does body mass index affect the early outcome of primary total hip arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty 2005; 20(7): 866–9.

- Namba R S, Paxton L, Fithian D C, Stone M L. Obesity and perioperative morbidity in total hip and total knee arthroplasty patients. J Arthroplasty 2005; 20(7 Suppl 3): 46–50.

- Nevitt M C, Epstein W V, Masem M, Murray W R. Work disability before and after total hip arthroplasty. assessment of effectiveness in reducing disability. Arthritis Rheum 1984; 27(4): 410–21.

- Nunley R M, Ruh E L, Zhang Q, Della Valle C J, Engh C A Jr, Berend M E, Parvizi J, Clohisy J C, Barrack R L. Do patients return to work after hip arthroplasty surgery. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26(6 Suppl): 92,98.e1–3.

- Rimm E B, Williams P, Fosher K, Criqui M, Stampfer M J. Moderate alcohol intake and lower risk of coronary heart disease: Meta-analysis of effects on lipids and haemostatic factors. BMJ 1999; 319(7224): 1523–8.

- Schemper M, Wakounig S, Heinze G. The estimation of average hazard ratios by weighted Cox regression. Stat Med 2009; 28: 2473–89.

- Scott C E H, Turnbull G S, MacDonald D, Breusch S J. Activity levels and return to work following total knee arthroplasty in patients under 65 years of age. Bone Joint J 2017; 99-B(8): 1037–46.

- Stigmar K, Dahlberg L E, Zhou C, Jacobson Lidgren H, Petersson I F, Englund M. Sick leave in Sweden before and after total joint replacement in hip and knee osteoarthritis patients. Acta Orthop 2017; 88(2): 152–7.

- Suarez J, Arguelles J, Costales M, Arechaga C, Cabeza F, Vijande M. Factors influencing the return to work of patients after hip replacement and rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996; 77(3): 269–72.

- Thumboo J, Chew L H, Lewin-Koh S C. Socioeconomic and psychosocial factors influence pain or physical function in Asian patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2002; 61(11): 1017–20.

- Tilbury C, Schaasberg W, Plevier J W, Fiocco M, Nelissen R G, Vliet Vlieland T P. Return to work after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014; 53(3): 512–25.

- Wetterholm M, Turkiewicz A, Stigmar K, Hubertsson J, Englund M. The rate of joint replacement in osteoarthritis depends on the patient’s socioeconomic status. Acta Orthop 2016; 87(3): 245–51.