ABSTRACT

This paper provides an overview of short and long-term art therapy treatment approaches, used in the USA, for military service members with post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury. The described clinical approaches are based on the theoretical foundations and the art therapists’ experiences in providing individualised care for the unique needs of the patient population. The art therapy models and directives are designed to be more therapist-led in the short-term model, moving on to an increasingly patient-led format in the long-term treatment model. The overall objectives of art therapy are: to support identity integration, externalisation, and authentic self-expression; to promote group cohesion; and to process grief, loss, and trauma. In addition, programme evaluation is used in both settings as a means to understand participants’ experiences and the perceived value of art therapy.

Background: PTSD and TBI in the military

As of 30 September 2011, the US Government Accountability Office (Citation2011) reported that approximately 2.6 million US military service members had already been deployed during the operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) era. Among a plethora of mental health issues, active-duty members are highly vulnerable to acquiring post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and traumatic brain injury (TBI). PTSD is an anxiety disorder resulting from the witnessing or experiencing of a physically and/or psychologically traumatic event. Individuals with PTSD have typically experienced intense fear, horror, or helplessness in relation to traumatic events, leading to behaviours of hyperarousal, negative mood, or cognitive associations, avoidance, and re-experiencing of the trauma (Bahraini et al., Citation2014). TBI involves altered or disrupted brain functioning caused by an external force (e.g. being hit by an object in the head, exposure to blasts), with memory loss, loss of consciousness, altered mental states (e.g. confusion), or neurological deficits (e.g. aphasia or loss of balance) experienced immediately after the event (Bahraini et al., Citation2014; Wall, Citation2012). Recent research has highlighted the co-occurrence of these severe diagnoses in SMs, with financial costs of treating these disorders estimated as high as $6 billion for those with PTSD and $910 million for those with TBI (Tanielian & Jaycox, Citation2008). A survey conducted from 2006 to 2010 estimated that PTSD has affected about 480,748 SMs (US Government Accountability Office, Citation2011). Additionally, 361,092 SMs were diagnosed as having suffered a mild, moderate, or severe TBI (Blakeley & Jansen, Citation2013; Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center, Citation2017). PTSD and TBI symptoms can often overlap, where individuals may experience anxiety, depression, cognitive deficits (e.g. memory loss, attention difficulties), irritability, and sleep disruptions, as well as embodied memory experiences (Kroch, Citation2009). Co-occurring issues with psychosocial health and well-being post deployment are an ongoing challenge for both veterans and those on active duty. Successful treatment of PTSD is difficult, and individuals struggling with PTSD relive the trauma years and sometime decades after the event(s) (Smyth, Hockemeyer, & Tulloch, Citation2008). PTSD and related mood disorders are relevant to civilian populations as well (e.g. victims of violence, natural disasters, accidents) with symptoms impacting individual functioning and social relationships.

Art therapy treatment for PTSD and TBI

Art therapy is a psychotherapeutic intervention that helps patients safely express and non-verbally externalise inner psychological experiences, especially fragmented memories resulting from trauma, as well as the identity-related, emotional struggles of physical and cognitive injuries sustained with TBI (Walker, Kaimal, Koffman, & Degraba, Citation2016). When an art therapist facilitates the art-making, the experience assists service members (SMs) in externalising their PTSD symptoms. Concurrently, individuals learn to manage overwhelming negative emotions by channelling them into creative expression. According to Collie, Backos, Malchiodi, and Spiegel (Citation2006), art-making, especially in the context of PTSD and the military, enhances feelings of safety and relaxation, generates positive and more regulated emotions, and promotes relational bonding. Art therapy furthermore can assist in the integration of fragmentary and sensory traumatic memories (Collie et al., Citation2006; Lobban, Citation2016; Walker, Citation2017) and foster reward perception through positive mood (Chilton et al., Citation2015; Kimport & Robbins, Citation2012). While research on TBI and art therapy is limited, individual and group art therapy have been found to be effective in helping TBI patients with emotional expression, socialisation, emotional adaptation to mental and physical disabilities, and communication in a creative and non-threatening way (Barker & Brunk, Citation1991; Dodd, Citation1975; Lazarus-Leff, Citation1998). Kline (Citation2016) points to the value of art therapy in supporting brain plasticity and highlights the art therapist’s ability to foster a safe and supportive environment while stressing the need for flexibility in TBI treatment. Herman (Citation1992a, Citation1992b) offered a model of trauma treatment that includes three stages: safety, remembrance and mourning, and reconnection. Collie et al. (Citation2006) extended this idea to the field of art therapy with a model for trauma including relaxation, self-expression, externalisation, positive emotions, and social connection. Jain et al. (Citation2012) and Tedeschi and Calhoun (Citation2004) argued for the potential opportunities for psychosocial development and creative change as a result of PTSD. Art therapy can help promote this creative developmental change with patients and concretise the experience with the artistic creation.

Integrating theory, practice, and programme evaluation

There has been increasing awareness of the need to publish articles linking theory and practice in art therapy to complement research being done in the field (Kaiser, Citation2015). This article will present the practices of two art therapy programmes for SMs with PTSD, TBI and comorbid mood disorders in multidisciplinary, government-funded treatment programmes including rationale and links for clinical programme choices.

The following sections describe the practices art therapists used to implement both short-term intensive and long-term clinical rehabilitation programmes. The long-term practice was built upon a core model created at the short-term treatment facility, pointing to the models’ ability to be expanded and successfully implemented, then adapted to meet the needs of the treatment setting. Using the structure of a practice article written by Drass (Citation2015), this article will provide a framework of describing specific art interventions while weaving in clinical theory, evaluation research, and case vignettes to illustrate the model. All artwork included in this article has been anonymised and consent has been given for the publication of artworks by their creators. The aim of this paper is to present the material in a way that will allow art therapists to utilise parts of this programme and adapt as necessary according to their own clinical practice and site needs.

It is also important to note the role that programme evaluation has had in the ongoing development of the art therapy programmes presented in this article. Kaimal and Blank (Citation2015) propose that programme evaluation can be a starting point for developing robust research programmes that connect theory and practice. As will be shown in the descriptions of the treatment models in the next section, programme evaluation can be integrated into practice in order to fine-tune the treatment methods, provide preliminary evidence of outcomes, and serve as a bridge to research.

Description of two treatment models

Model one: short term art therapy in an integrative medical care context

Since 2010, art therapy has been utilised as a treatment method for military SMs as part of a multi-disciplinary approach at the National Intrepid Center of Excellence (NICoE) at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, MD. The art therapist at this site established an intensive outpatient (IOP) treatment model to treat TBI, PTSD, and co-occurring mood disorders by incorporating both group and individual weekly art therapy sessions in a dedicated studio space (Walker, Citation2017; Walker et al., Citation2016).

Once enrolled in the four-week IOP NICoE programme, up to six SMs are admitted weekly and follow a cohort-based interdisciplinary template which integrates strategically designed art therapy sessions over the four-week period. All six service members partake in group art therapy sessions to include mask-making and montage painting, and each service member receives at least one individual art therapy evaluation which is tailored to the SMs’ needs. If the art therapy sessions are considered particularly beneficial for an SM (based on the observations of the art therapist, and SM and treatment team feedback), follow-up sessions are scheduled over the final two weeks of the programme. Walker’s (Citation2017) rationale for implementing the following directives can be found in detail in Howie’s book, Art Therapy with Military Populations: History, Innovation, and Applications.

At the end of Week 1 of the four-week programme, SMs engage in a group art therapy mask-making directive. Masks were selected as the directive because they help focus the patients on their own experiences with TBI and PTSD and offer a means to express inner mental states through a safe externalised representation (Walker, Citation2017). This is deliberately set up as a group session to give SMs the opportunity to connect with peers who undergo similar experiences, thus reducing isolation. SMs are given a pre-made papier-mâché mask and art media including paints, clay, markers, and miscellaneous found objects to alter the mask any way they choose. An example directive provided by the art therapist is as follows:

Masks are inherently connected to identity. You can choose to focus on the identity of yourself or someone significant to you. Themes that tend to come up in the mask are identity, split sense of self, who I am when I am deployed versus who I am when I’m at home, negative side versus positive side, outside-self versus inside-self, depiction of the injuries themselves, transitions, grief and loss, or trauma. You can choose to fall within any of these categories or create a category of your own. You can create depictions that are metaphorical or concrete. While you’re starting to think about what you may do, I’m going to walk around the room and I’ll show you everything that I have available here. So you can either sketch, plan out what you want to do, or you can just open the cabinet and grab the first paint color that speaks to you and dive right in and see where it guides you.

Figure 1. Mask base and a completed mask. Each service member is given a blank papier-mâché mask (left) and asked to transform the template to represent whatever he/she would like regarding their identity. A sailor chose to represent the different facets of himself (right), depicting the face he shows the outer world in contrast with the dual parts of his inner personality, including a bright, peaceful side and a dark, tumultuous side.

Woven between the group art therapy sessions are individual art therapy treatment sessions during which the art therapists explore SMs’ personal goals for treatment and implement projects based on these goals (Walker, Citation2017). SMs may return for follow-up sessions based on need. The SMs are also invited to return to work on their individual art therapy projects during open studio times in the third and fourth week of treatment.

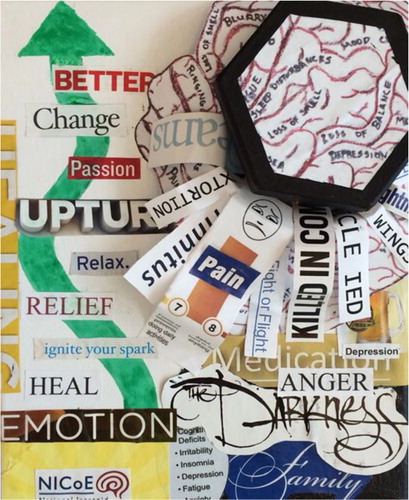

In the final week of treatment at the NICoE SMs are introduced to montage paintings. Montage paintings are a way to integrate patient experiences in one space and form a layered and non-linear narrative (Walker, Citation2017). Each SM is given an 20.32 cm × 25.4 cm canvas, and the project is introduced as a mixed media artwork in a group art therapy session. The art therapist gives the following directive:

Some people choose to just paint and then they might use collage to embellish certain things, or they may collage and then paint to embellish certain things or they may go back and forth. You can document or process something from the past, or focus on where you are currently, or on hopes, goals, or concerns for the future. There are two different ways to approach this, you can either have an idea in your mind of exactly what you want it to look like and you can spend the session actualising that image, or you can have no idea of what you want it to look like, no idea what you want it to be about and just spend some time going through magazines, cutting out any words or images that resonate with you for whatever reason. It can be a really insightful process to then organise what you’ve collected on to your canvas.

Figure 2. Montage painting. Each service member is given a blank 20.32 cm × 25.4 cm canvas and invited to layer art media to represent a theme, often resulting in the depiction of past/present/future, and what the service member feels has changed (or what they learned) during treatment. In this montage painting, a sailor chose to integrate a box that has ruptured under the pressure of keeping things (negative words, feelings, images, dreams, and phrases) inside. The work also features a meandering green arrow leading from the NICoE logo with positive words of healing along its path.

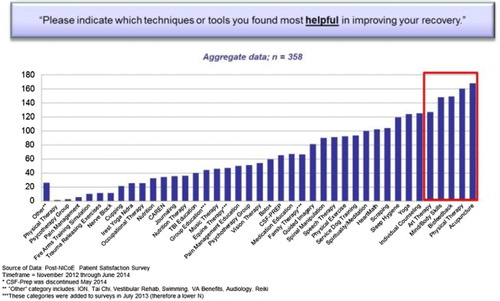

In addition to the masks and montage paintings, SMs have the opportunity to engage in therapeutic writing sessions and creative writing workshops along with several other treatments including, but not limited to, medical and nursing care, physical therapy, nutrition counselling, individual counselling, family therapy, animal-assisted therapy, music therapy, and mind–body based interventions. In order to determine the comparative usefulness of the different approaches, the site conducted an internal programme evaluation. See .

The responses in indicate that SMs in model one rated their experiences with art therapy among the top five most helpful techniques at the NICoE. This finding elevated the value of art therapy at the site, helped expand the programme to additional sites, and enabled external funding support for research. In addition, from 2015 onwards, the NICoE integrated with the TBI Outpatient Clinic at Walter Reed and introduced a long-term treatment component within the art therapy programme. These referral-based individual outpatient sessions occur once weekly at the NICoE for an hour for as long as clinically appropriate for the patient.

Model two: long term art therapy in an outpatient integrative medical care context

In addition to the NICoE at Walter Reed Medical Center at Bethesda, active duty SMs are eligible to receive art therapy services through a programme at one of their satellite centres, the Intrepid Spirit One (ISO) at the Fort Belvoir Community Hospital in Northern Virginia. The art therapy programme at ISO is modelled after the programme at the NICoE; however, it extends beyond the four weeks and touches upon later stages of trauma work. ISO is a more traditional outpatient centre where active duty and retired SMs live and work on the military base or in the surrounding community. Upon entering the programme, physicians evaluate each SM and refer an SM to art therapy based on the individual’s treatment goals. In accordance with widely acceptable trauma treatment, emphasising structure and safety, remembrance and mourning, and reconnection (Herman, Citation1992a), the art therapy programme at ISO was created using a stage-based protocol. Art therapy is offered at three levels of treatment protocols, with programme evaluations occurring at the completion of each level.

Level 1 treatment protocols

The ISO art therapist refers to Level 1 as an ‘introduction’ to art therapy with process-focused art-making projects that are based heavily on the art therapy programme at the NICoE in Bethesda. SMs receive art therapy as part of their treatment for TBI/PH needs and, when referred to art therapy, make an initial three-week commitment to group art therapy. For majority of patients, art therapy is a new experience, and the art therapist therefore provides an introduction to the SMs as follows:

Art therapy is not like art class. Instead of being product-oriented where you’re worried about what something’s going to look like in the end, I’ll give you pretty open-ended springboards, and it’s up to you what direction you want to take things in. Follow your intuition and be spontaneous in your art-making. If you feel like using a certain color just use it. If you feel like creating a certain image just create it and then we’ll take a look at it, talk about it, and make meaning from it.

Level 2 treatment protocols

Level 2 provides further opportunity for art-making for increased insight, identity development, emotional regulation, and empathy and support for self and others. Tasks allow service members to gain understanding into the effects of their past experiences and identify who they want to be and how they will get there. Through discussions and peer support, patients develop stronger connections with cohort peers. The projects help them explore a new sense of identity, recognise positive aspects of self and career, and tap directly into issues of grief and loss.

Level 2 groups are held in a cohort format for a two-hour group that meets once a week for six weeks. Since SMs have an introductory understanding of art therapy and adequate comfort level with the art therapist and the space, they can begin to explore deeper issues of accepting changes in their lives. At the same time, it is important for the art therapist to be able to gauge the level of trauma treatment in relation to the SM’s duties and responsibilities. Since the programme at ISO is an outpatient model, SMs must juggle treatment with their daily routines.

Art therapy is in the unique position of producing a tangible product as a result of its process. Art also provides an opportunity to release and contain traumatic material. Thus, art therapists are called to use their clinical judgement and focus on the needs of individual SMs throughout treatment. The following describes the tasks of Level 2 in detail. It is important to note that the following directives can be emotionally provocative and are only facilitated by trained art therapists who are able to safely process and contain traumatic material. Service members enrolled in Level 2 groups have been deemed appropriate for the sessions by their clinical treatment team.

Week 1: greatest fear/greatest comfort

For this task, the art therapist provides each SM with two pieces of 22.86 cm × 30.48 cm drawing paper and asks them to depict their ‘greatest fear at the moment,’ on one page and ‘greatest comfort at the moment’ on the other. They are instructed to use any two-dimensional media of their choosing and they can draw, paint, or collage. Both directives are given at the same time, allowing the SM to decide the order of task development. This task allows SMs to externalise their main areas of concern and creates an environment in which they feel less alone in their struggles. It also enables them to shed equal light on the positive resources in their lives, providing an opportunity that illuminates what elements of life they can focus on in order to counteract negative feelings and experiences in an effort to create greater balance ().

Figure 4. Collage representing greatest fear and greatest comfort. A soldier created two collages, one to represent her greatest fear at the moment and one to represent her greatest comfort at the moment. Her comfort collage represents herself, ‘little tiger’, as she is currently working to find herself and take care of her own needs. Additional comforts depicted in the collage are the importance of family, home as sanctuary, and enjoying nature. Her fear image is represented by a turbulent storm which alludes to her work, feeling as if she’s drowning because of the constant painful experiences that make up her work, telling her case’s stories but not getting a chance to tell her own (until now), feeling no peace, taking harsh words personally. Her image was created with vertical lines, representing how she feels caged in, jailed. In sharing the images she spoke of taking the opportunity to tell her story now as it is important for her to survive her last couple of years of her military career.

Week 2: dialogue between self and entity of choice

For this task, SMs are asked to choose two different coloured pens and write a dialogue between themselves and an entity of their choice. The task is based on the ‘dialogue journal exercise’ described in Kathleen Adams’s book Journal to the Self (Citation1990). They are provided with a list of options of entities with which they can write: a person, an event or circumstance, something related to the body, an emotion, a society, or inner wisdom. Options are expounded upon to assist with their decision making process. For example, they can select a person from: their past, present, or future; or someone already dead, still alive, or perhaps not yet born. Writing to a person is helpful when working on an unresolved business or to gain alternative points of view. They may also choose to address an event or circumstance. Writing to an event or circumstance can assist in ‘meaning making’ or clarification of unconscious desires. They can choose to write to something related to the body, such as a body part, an injury, an illness, pain, or an addiction. They can also choose to write to society or an emotion, such as anger or love. Some write to inner wisdom, while others take a spiritual approach and write to God, Jesus, or a spiritual voice inside themselves. The SMs are instructed not to plan this out but let it be a naturally unfolding dialogue. This exercise yields material that is insightful and expressive, and it typically leads to fruitful discussion and dialogue among group members.

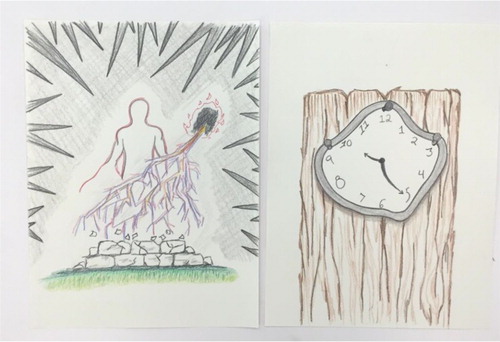

Week 3: depict your soul

For this task, each SM is given one piece of paper and then told ‘Depict your soul. You may use whichever drawing materials feel right, to depict your soul.’ They have 40 minutes for this part of the project, and a variety of drawing supplies are set out from which they may choose to use. At the 40 minute mark they are given another piece of paper and asked to: ‘Depict what your soul needs to be nourished to a state of greater well-being.’ ()

Figure 5. Depicting the soul. A soldier created these drawings, the first a depiction of his soul, and the second a depiction of what his soul needed to be nourished to a state of greater wellbeing. His soul depiction shows a soul ‘being attacked’ by internal and external elements, with a wall of anger as defence against the elements. There is a wall being broken down with ‘greener grass’ on the other side. His nourishment image shows a distorted clock, which represents his realisation that even when engaged in multiple therapies, profound change, and ultimately the healing of the soul, ‘takes time’.

The SMs find this project helpful because it provides an opportunity to truly think about and externalise how they see themselves at their core. It also illustrates the inner resources and strengths they contain within from which they can draw in order to become who they want to be. This session often proves to be a turning point in treatment where they begin to see the changes they can make in the moment in order to achieve positive change. They also tend to share resources with each other during verbal processing. One person might say, ‘I feel like I should get out in nature more,’ and someone else might say, ‘Oh these are all the great nonprofits I’m part of. They take me hiking, kayaking and stuff. It’s really helpful.’ They begin to start reaching out to each other and their communities to see where opportunities for connection might lie.

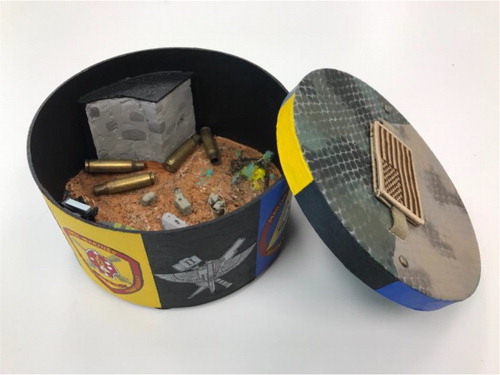

Weeks 4–6: box project

During the fourth, fifth, and sixth sessions of Level 2, SMs work on a long-term box project. Boxes are frequently used in art therapy and can help with containment of obtrusive emotions or flashbacks as well as boundary setting and personal control (Drass, Citation2015). The SMs are instructed to celebrate their aspects of career and self on the outside of the box and commemorate or memorialise aspects of career or self, or lost friends and colleagues, inside the box. When choosing the size and shape of their container, SMs are reminded to think about objects they have at home from their personal military history that may be hidden but not thrown away, as these may be meaningful and suggest they pick a container sized to fit those items. Working on a longer-term project in a structured setting such as this can help the SMs not only plan and think ahead, but also to take risks, make choices, and utilise problem-solving skills (Drass, Citation2015). This project was created in response to hearing SMs discuss their feelings of invalidation and express frustration over doctors telling them to accept their ‘new normal’. Here, SMs can take as much time as needed to focus on all the aspects of career and self that they are proud of and recognise that these are important parts of their identity. Simultaneously, they can work on areas of grief and loss on the inside of the box, which is more private, and which can be opened or closed as the SM desires, which helps increase their sense of control.

Some SMs create memorial spaces on the inside by incorporating items such as remembrance bracelets or photographs of lost comrades. Others use the inside to depict the scene of a traumatic event, parts of themselves that they miss, or abilities that they don't have anymore. This project gives SMs a space to feel validated in their new reality and to begin to grieve and address the invisible wounds of war that they have yet to articulate. It also provides an opportunity to accept the current moment in their lives and notice positive aspects. These boxes serve as a concrete reminder of both who they are and what they have lost. Most SMs make a strong investment into this box project and take it with them after treatment ( and ).

Figure 6. Celebration/commemoration box. A marine created this box, collaging personal photographs around the outside walls to show how on the outside ‘everything looks pretty’ – he looks good, whole, smiling with friends and family. The inside of the box shows how internally he feels fractured by memories that are burned into his soul, some of which is represented by photographs of comrades who have died collaged onto the inside walls. The patch glued to the inside of the box lid is upside down and torn apart to show feeling in distress. The centre of the box contains a volcano with Pandora’s box to show a hole into Hell he personally experiences.

Figure 7. Celebration/commemoration box. A marine created this celebration/commemoration box, on the outside walls of which he rendered intricate emblems that represent the chronology of jobs he has had which have shaped him throughout his career, the experiences, positive and negative, that make him who he is today. Within the box he carefully created a scene that is comprised of elements that represent his four significant ‘close calls’ from combat.

Level 3 treatment protocols

Level 3 consists of further work to address specific goal areas that were more clearly defined throughout work created in Levels 1 and 2. Most of the Level 3 therapeutic sessions occur on an individual basis; however, they can also be held in open studio groups and through community arts participation. Level 3 comprises both open studio groups and individual art therapy sessions and focuses on deeper self-expression, externalisation, exploration, and processing based on the individual.

Individual art therapy sessions

In these sessions, patients delve deeper into self-expression, externalisation, exploration, and processing based on their individual needs. The art therapy work tends to focus on identity, sense of self, transition, relaxation strategies, greater understanding of personal triggers for trauma responses or emotional reactions. These experiences are designed to lead to greater emotional regulation and self-control, address disenfranchised and complicated grief and loss (Doka, Citation2002; Shear, Citation2015), process trauma, work through moral injury (Shay, Citation1994), and reconnect with others. The art therapist meets individually with each SM to evaluate goals and discuss moving forward with art therapy. Approximately 30% of the SMs naturally end art therapy treatment at this time due to their treatment goals having been met, or retiring and moving out of the area. Almost 70% of the SMs continue with art therapy at ISO to focus on individual goals such as processing specific traumatic events and losses in accordance with Stage 2 trauma treatment (Herman, Citation1992a, Citation1992b).

The art therapy work addresses SMs’ individual needs including themes of identity, sense of self, transition, and relaxation strategies. It may also facilitate greater understanding of personal triggers for trauma responses or emotional reactions. This understanding can lead to greater emotional regulation and self-control and to address complicated and disenfranchised grief, trauma processing, work on moral injury, and reconnecting with others.

The art therapist can select a variety of tasks for these individual sessions. Depending on the individual and their main goals for art therapy treatment, directives may focus more heavily on meditative or relaxation-based tasks, art experientials to further insight and self-expression, or longer-term projects that allow SMs to work through complicated trauma, moral injury, or grief and loss. Individual sessions may provide SMs an opportunity to engage in art making that allows them to experience a state of flow (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1990). Sessions may also be exploratory, for instance when SMs are directed by the art therapist to externalise through visual metaphor their internal and external experiences in order to gain deeper understand of self, specifically what underlies their physiological and emotional reactions to environmental triggers. Sessions can also include the use of work that is more obviously therapist-directed, such as use of the Intensive Trauma Therapy graphic narrative, developed by Gantt and Tinnin (Citation2007, Citation2009), in which the art therapist has been trained. Through this technique, which includes drawing a storyboard of the traumatic event according to stages in the Instinctual Trauma Response (Gantt & Tinnin, Citation2007) and creating a narrative based on the drawings, the SMs are able to work through detailed trauma memories in a safe and structured manner.

Many SMs utilise art therapy to work through their grief, which is done in a variety of ways, to include: creating memorial stones (memorial collages on the undersides of flat-bottom glass beads); memorial books (handmade books in which each page becomes the canvas for expressive artwork reflecting on individuals who have died); compilation of memorial tiles (tiles created for each deceased individual laid together); sculptures of Kevlar helmet, boot, and rifle combat cross memorials created to grieve specific individuals; and drawn, painted, or sculpted portraits of the deceased (Jones, Citation2017; Mims & Jones, in press). Additionally, SMs may also create a series of past, present, and future self-portraits to work through identity issues (Carr, Citation2014, Citation2017); develop artwork to capture the culmination of one’s career; or engage in a multitude of other art tasks to address stuck points that were discovered in earlier stages of art therapy treatment.

SMs who have reached a point where they are working on longer-term, self-directed, product-oriented artworks, are invited to join Open Studio groups sessions where they gather to work side-by-side on projects that allow them each to process their experiences at a deeper level while simultaneously benefiting from the development of camaraderie that is fostered in the space.

Open studio art therapy groups

During the Level 3 open studio groups, SMs get to work on long term individual art projects. At this point in treatment, there is already a knowledge base and understanding of the art therapy process; thus, SMs are able to work independently on self-guided projects amongst a community of their peers. The group meets each week for two hours. At this stage, the role of the art therapist is more of a consultant in the art-making journey, rather than someone giving specific art tasks or interventions. Throughout this process of self-exploration, the art therapist is able to actively process in ‘real-time’ what is happening for the SM as they are creating their art. In the open studio, SMs are sharing a space while they are all working on their own projects; at times, the art therapist acts more like a teacher in that environment. For example, one SM might want to create an ominous charcoal drawing of a demon that represents PTSD, and the art therapist might help him learn some charcoal drawing techniques. Another SM may want to create a realistic looking self-portrait painting of his commander who was killed; the art therapist might help him develop more realistic painting techniques. By working in this way, SMs can develop a sense of artistic sensibility which Thompson (Citation2009) described as ‘an awareness of the artistic self that permits a certain freedom of responsiveness … [that] informs affective and cognitive reactions to his or her internal process and the wider environment’ (p. 160). While this group may appear to be more product-oriented, the cognitive problem-solving processes at play at this level of artistic production can help to re-route neural pathways in the brain that tend to go offline as a result of PTSD and/or TBI. In addition to the open studio group, the art therapist continues to meet individually with SMs, twice a month, to have more personal and confidential conversations about what they have been creating in the group.

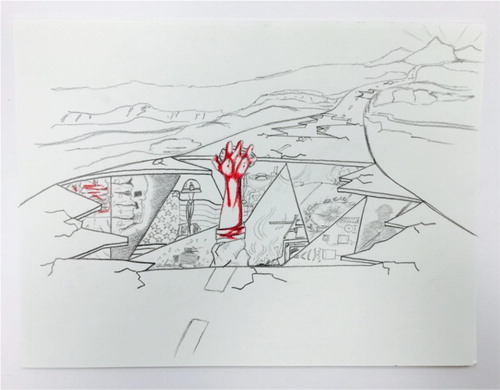

include examples of artwork made in Level 3 individual sessions.

Figure 8. Level 3 open studio artwork. A soldier drew this image (in progress) of a road with a hole that shows fragments of multiple combat experiences, his efforts to emerge from the hole, to travel down the road with holes that become smaller as the road moves forward to a more hopeful area in the distance.

Figure 9. Assemblage made in individual sessions. A soldier created this assemblage entitled ‘The Evidence of True Faith and Allegiance’ which provides a glimpse of what can be seen on the floor of any forward medical station. The artwork depicts the essence of the oath soldiers take, and following through with the oath to whatever trauma may occur or whatever end may come.

Figure 10. Mixed media artwork. A marine created this mixed media battlefield cross sculpture to memorialise a best friend and comrade who was killed in action. Creating the memorial allowed him to feel he paid his respects.

Figure 11. Tile collage artwork. A marine created this mixed media artwork to work through complicated grief of over 60 comrades he knew who were killed in action or died since returning home (Note: This photo has been blurred to protect the confidentiality of the fallen). The creation of the memorial tiles allowed him to process the death and reflect on the life of each individual, and the matting and framing of the tiles with the American flag motif, seeming as if a flag is draped over a casket, allowed him to move from focusing on the traumatic nature of the deaths to honourably laying each person to rest. His artwork evolved to capture ‘honour’ and he was able to release negative pent up energy as result of the process.

Programme evaluation and programme design

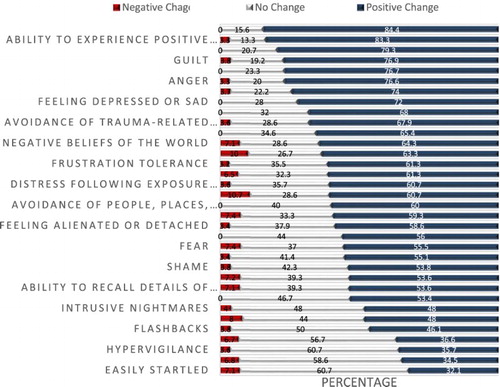

Programme evaluations for Model Two are built into all levels of treatment through a customised survey given to participants at the end of each level. These help the art therapist refine clinical practice, provide evidence on art therapy to other healthcare providers and ensure quality care. The findings were summarised in collaboration with a University partner (co-authors on this paper). summarises patient perceptions of the contributions of art therapy to changes in clinical symptoms.

As can be seen from , art therapy was found to be most impactful for a range of symptoms. It is notable that the identity integration experiences reduced flashbacks and nightmares, helped participants to focus on aspects of self that are deeply impacted by PTSD and TBI, and positively impacted SMs in their self-reported ability to experience positive emotions, improve their sense of self, and find meaning in life.

Discussion and implications

This paper presents an art therapy clinical practice protocol implemented within integrative treatment programmes for active duty SMs with PTSD and TBI in the USA. Treating PTSD, TBI, and co-occurring mood disorders in active duty SMs poses challenges. The programmes presented here point to the value of art therapy as a component of an integrative treatment model that aids in non-verbal discoveries for SMs along the themes of physical and psychological injuries, relational support and losses, military identity, community identity, existential reflections, questions, transitions, and resolving a conflicted sense of self (Walker et al., Citation2017).

Art therapy can offer insights into the lived experiences of SMs struggling with PTSD, TBI, and co-occurring mood disorders. Since much of the current literature on PTSD and combat trauma focuses on veterans, the authors’ aim is to illuminate what is being done in these innovative and structured treatment programmes. The art therapy programmes described here have grown and adapted in accordance with ongoing participant surveys, in addition to the most current theory and best practices for treating PTSD and TBI. The evaluations served to provide aggregate data on SMs’ perceptions of the value and contributions of art therapy in their overall treatment experience. At each site, the programme evaluations were helpful in documenting patient experiences and communicating the perceived impact of art therapy to staff and other healthcare professionals. This is a valuable practice that should be integrated into art therapy programming whenever possible. It is also helpful to seek out partnerships with researchers and/or local universities to assist with data analysis and then use the findings to both improve clinical practice and to advocate for art therapy programming. Presenting the treatment programme examples in this paper also highlights the importance of providing art therapy literature that describes the intersection between research, theoretical frameworks, programme evaluation, and current art therapy practices.

As can be seen from the treatment plans and descriptions, there are important differences between group and individual art therapy for service members with PTSD and TBI. The goals of group art therapy are reducing isolation, building relationships, and increasing communication through the shared process of creating and talking about their artwork together. Individual art therapy helps patients focus on their own specific challenges of personal grief, loss, and trauma processing that they might feel uncomfortable sharing in a group format. Most patients begin in the structured group setting and gradually proceed to individual and open studio projects. The transition is from therapist led directives to patient led projects in order to facilitate independent functioning and psychosocial development from the symptoms.

Transition from military to civilian life happens in an interpersonal context (DeLucia, Citation2016). One of the main goals of programmes such as the NICoE and ISO is to assist SMs in reintegration into their respective communities, and art has been one way to help bridge that gap. Whether it is through the display of their masks throughout the treatment facilities or through partnerships with local art studios that offer classes to SMs, a visual community is being created that lays out a context for healing. It is of note that the art therapy programmes discussed in this article have received extensive media attention, and it appears that, through partnerships such as with the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), more attention is being given to the value of art therapy as a treatment modality for people with PTSD and TBI. The art products, especially the masks, have helped visualise the patients’ challenges and struggles including their invisible wounds (Lobban, Citation2014; Walker, Citation2017). This media attention has helped bring art therapy to the forefront as a potential treatment modality for SMs, helping in particular to integrate their experiences, externalise long standing symptoms, communicate with family and caregivers, and address deep-seated grief and loss.

Historically, successful treatment of PTSD and TBI has been difficult for SMs due to a myriad of co-occurring issues with psychosocial health and well-being post deployment. Within the programmes presented here, there are a variety of factors involved at a number of levels driving change in treatment for SMs with PTSD and TBI. The art therapy programmes were created to actively engage SMs in treatment and offer them forms of self-expression that are not limited to verbal language alone. The placement of these programmes within interdisciplinary treatment centres and through partnerships with other agencies such as the NEA and university research programmes provide an example of interdisciplinary collaboration and a model of integrative care for SMs struggling with clinical symptoms. The role of ongoing programme evaluation helps art therapists step away from their own heartfelt assumptions of what happens in treatment, and allows for the SMs to have an active voice in advocacy, quality of care and the development of new programmes that serve their needs. The increased awareness of the role of arts in healing and the physical examples of art created by SMs have created a space for a new visual culture to emerge within this community which works to de-mystify the practice of art therapy.

It is important to note that, while evaluating the value of art therapy within the context of interdisciplinary clinics, art therapy treatment emerges as a significant agent of change that occurs within an SM’s recovery. The art therapy tasks described throughout this paper provide SMs with an opportunity to take a deep look into a reflection of themselves in an attempt to integrate fragmented parts of their emotions, memories, and lived experiences. Processing the art products allows them to discover what may have been hidden beneath the more easily identified symptoms or issues that caused them to seek treatment in the first place. Change occurs in art therapy through disruption, specifically through engagement with media that can be manipulated, destroyed, and transformed, e.g. the blank surface of the mask becomes disrupted the moment paint is applied or found objects are attached. Many SMs describe art therapy as having the precision of a scalpel- that it is only through the art therapy process that they are able to ‘cut through the clutter’ of their lives and get at the heart of the content they are attempting to understand and overcome. Art therapy accesses the underlying core of their physical symptoms, interpersonal issues, emotions, and behaviours, which many refer to as their ‘personal enemy’.

SMs describe their art therapy journey as one that enables them to develop strategies to combat these ‘personal enemies’, leading to an experience of control over their symptoms and experiences. The interpersonal nature of art therapy allows for a sense of reintegration and recovery to occur, and gives a tangible form to their core issues. The artworks produced become evocative tools that act as a visual voice, improving communication and relationships with themselves and others. Within the evaluation SMs report finding hope for the future and a significant increase in their ability to experience positive emotions, with the creation of artwork playing a significant role as an agent of change to SMs’ sense of self. The creation of an art product under the guidance of a trained art therapist lays the groundwork for SMs to use creativity to express their ongoing, and often internal, dialectical dialogues.

Conclusion

This paper provides an overview of art therapy approaches for military SMs facing post-traumatic stress, traumatic brain injury, and psychological health conditions in the USA. The session descriptions for short term and long term care provide guidance to art therapists working with this population. Art therapy sessions in both of these settings were conducted in the context of an integrative medical care setting by credentialed art therapists. In addition to clinical approaches, the paper also highlights the value of programme evaluation to document perceptions, outcomes and data to advocate for art therapy services. These approaches point to a need for clinicians to balance evidence-based treatment modalities that focus on symptom reduction as well as the cultivation of a deeper understanding of self in order to work to resolve internal conflicts so often experienced by SMs. The art therapy journey serves as an agent of change, during which SMs establish a new sense of self as creator rather than destroyer, as productive and efficacious instead of broken, as connected to others as opposed to isolated, and in control of their future, not controlled by their past.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. The views express in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army/Navy/Air Force, Department of Defense, or US Government.

Notes on contributors

Jacqueline P. Jones, MEd, MA, ATR, is a Creative Arts Therapist at the Intrepid Spirit Center at Fort Belvoir Community Hospital, where she provides art therapy services to active duty service members recovering from traumatic brain injury and psychological health conditions. With support from the National Endowment for the Arts, she established the Creative Arts Therapies programme at the Intrepid Spirit Center at Fort Belvoir after interning at the National Intrepid Center of Excellence. She is an art therapist within Creative Forces: The NEA/Military Healing Arts Network, and she has focused on providing art therapy, program development and expansion, and on exploring and identifying the unique value of art therapy in interdisciplinary rehabilitation settings for service members recovering from invisible wounds of war. Prior to pursuing a career in art therapy, Jackie was an art educator in Fairfax County Public Schools. She earned her Master's degree in Art Therapy from the George Washington University, and her Master's and Bachelor's degrees in Art Education from the University of Maryland. She is a practicing visual artist.

Melissa S. Walker, MA ATR, moved to the National Capital Region in 2008 to work for the Department of Defense after earning a Master's in Art Therapy from NYU. Ms. Walker developed and implemented the NICoE Healing Arts Program at Walter Reed Bethesda, MD, US, to explore the integration and research of the creative arts therapies for service members with traumatic brain injury and psychological health concerns. Ms. Walker currently serves as the programme's coordinator and also acts as lead art therapist for Creative Forces: the NEA/Military Healing Arts Network - a collaboration aimed to expand clinical and community arts access for the military population.

Jessica Masino Drass, MA, ATR-BC, is currently a research fellow at Drexel University in the Creative Arts Therapy PhD programme working under Dr. Girija Kaimal. Jessica specializes in the treatment of complex trauma and dissociation, and has published articles on Treating Borderline Personality from a Dialectical Behavior Therapy framework and Punk Rock Art Therapy. She is a graduate of Drexel University’s art therapy program, and also has an MA in School Psychology from Rowan University, and BA in Fine Art from Rutgers University. Jessica also co-founded Wise Mind Creations, LLC, a community art studio specialising in mindfulness training.

Dr. Girija Kaimal is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Creative Arts Therapies at Drexel University. Her research examines physiological and psychological outcomes of creative visual self-expression. Girija currently leads two federally funded studies examining arts-based approaches to health among caregivers and military service members. She has led longitudinal evaluation research studies examining arts-based approaches to leadership development and teacher incentives and won national awards for her research. Girija is the Chair of the Research Committee for the American Art Therapy Association, Assessment Fellow for Drexel University, and, is a practicing visual artist. Dr. Kaimal has a Doctorate in Education from Harvard University, a Master’s in Art Therapy from Drexel University, and a Bachelor’s in design from the National Institute of Design in India.

ORCID

Jacqueline P. Jones http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8484-2891

Melissa S. Walker http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9375-567X

Jessica Masino Drass http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9867-4019

Girija Kaimal http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7316-0473

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, Kathleen. (1990). Journal to the self. New York, NY: Grand Central Publishing.

- Bahraini, N. H., Breshears, R. E., Hernández, T. D., Schneider, A. L., Forster, J. E., & Brenner, L. A. (2014). Traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 37(1), 55–75. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2013.11.002

- Barker, V. L., & Brunk, B. (1991). The role of a creative arts group in the treatment of traumatic brain injury. Music Therapy Perspectives, 9(1), 26–31. doi: 10.1093/mtp/9.1.26

- Blakeley, K., & Jansen, D. J. (2013). Post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health problems in the military: Oversight issues for congress. Library of congress, Washington DC: Congressional Research Service.

- Carr, S. (2014). Revisioning self-identity: The role of portraits, neuroscience and the art therapist’s ‘third hand’. International Journal of Art Therapy, 19(2), 54–70. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2014.906476

- Carr, S. (2017). Portrait therapy: Resolving self-identity disruption in clients with life-threatening and chronic illnesses. London: Jessica Kingsley.

- Chilton, G., Gerber, N., Bechtel, A., Councill, T., Dreyer, M., & Yingling, E. (2015). The art of positive emotions: Expressing positive emotions within the intersubjective art making process. Canadian Art Therapy Association Journal, 28(1), 12–25. doi: 10.1080/08322473.2015.1100580

- Collie, K., Backos, A., Malchiodi, C., & Spiegel, D. (2006). Art therapy for combat-related PTSD: Recommendations for research and practice. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 23(4), 157–164. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2006.10129335

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper and Row.

- Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center. (2017). DoD Worldwide numbers for TBI [PDF file]. Retrieved from http://dvbic.dcoe.mil/files/tbi-numbers/DoD-TBI-Worldwide-Totals_2000-2016_Feb-17-2017_v1.0_2017-04-06.pdf

- DeLucia, J. M. (2016). Art therapy services to support veterans’ transition to civilian life: The studio and the gallery. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 33(1), 4–12. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2016.1127113

- Dodd, F. G. (1975). Art therapy with a brain-injured man. American Journal of Art Therapy, 14(3), 83–89.

- Doka, K. (2002). Disenfranchised grief: New directions, challenges, and strategies for practice. Champaign: Research Press.

- Drass, J. (2015). Art therapy for individuals with borderline personality: Using a dialectical behavior therapy framework. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 32(4), 168–176. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2015.1092716

- Gantt, L., & Tinnin, L. (2007). Intensive trauma therapy of PTSD and dissociation: An outcome study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 34, 69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2006.09.007

- Gantt, L., & Tinnin, L. (2009). Support for a neurobiological view of trauma with implications for art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 36, 148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2008.12.005

- Herman, J. L. (1992a). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 377–391. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490050305

- Herman, J. L. (1992b). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence- from domestic abuse to political terror. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Jain, S., McMahon, G. F., Hasen, P., Kozub, M. P., Porter, V., King, R., & Guarneri, E. M. (2012). Healing touch with guided imagery for PTSD in returning active duty military: A randomized controlled trial. Military Medicine, 177(9), 1015–1021. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-11-00290

- Jones, J. (2017). Complicated grief: Considerations for treatment of military populations. In P. Howie (Ed.), Art therapy with military populations: History, innovation, and applications (pp. 98–110). London: Routledge.

- Kaimal, G., & Blank, C. L. (2015). Program evaluation: A doorway to research in the creative arts therapies. Art Therapy: The Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 32(2), 89–92. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2015.1028310

- Kaiser, D. H. (2015). What should be published in Art Therapy? What should art therapists write about? Art Therapy: The Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 32(4), 156–157. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2015.1107376

- Kimport, E. R., & Robbins, S. J. (2012). Efficacy of creative clay work for reducing negative mood: A randomized controlled trial. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 29(2), 74–79. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2012.680048

- Kline, T. (2016). Art therapy for individuals with traumatic brain injury: A comprehensive neurorehabilitation-informed approach to treatment. Art Therapy: The Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 33(2), 67–73. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2016.1164002

- Kroch, R. (2009). Living with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)-a hermeneutic phenomenological study (Doctoral dissertation). University of Calgary.

- Lazarus-Leff, B. (1998). Art therapy and the aesthetic environment as agents for change. Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 15(2), 120–126. doi: 10.1080/07421656.1989.10758723

- Lobban, J. (2014). The invisible wound: Veterans’ art therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy: Formerly Inscape, 19(1), 3–18. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2012.725547

- Lobban, J. (2016). Factors that influence engagement in an inpatient art therapy group for veterans with post traumatic stress disorder. International Journal of Art Therapy: Formerly Inscape, 21(1), 15–22. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2015.1124899

- Mims, R. & Jones, J. (in press). Art therapy to address disenfranchised grief in military service members. In R. Jacobson & M. Wood (Eds.), Art therapy in hospice and bereavement care. London: Routledge.

- Shay, J. (1994). Achilles in Vietnam: Combat trauma and the undoing of character. New York: Scribner.

- Shear, M. K. (2015). Complicated grief. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(2), 153–160. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1315618

- Smyth, J. M., Hockemeyer, J. R., & Tulloch, H. (2008). Expressive writing and post-traumatic stress disorder: Effects on trauma symptoms, mood states, and cortisol reactivity. British Journal of Health Psychology, 13(1), 85–93. doi: 10.1348/135910707X250866

- Tanielian, T., & Jaycox, L. (2008). Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Pittsburgh, PA: RAND Corporation.

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01

- Thompson, G. (2009). Artistic sensibility in the studio and gallery model: Revisiting process and product. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 26(4), 159–166. doi: 10.1080/07421656.2009.10129609

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2011). VA mental health: Number of veterans receiving care, barriers faced, and efforts to increase access (GAO-12-12) [PDF file]. Retrieved from http://www.gao.gov/assets/590/585743

- Walker, M. (2017). Art therapy approaches within the National Intrepid Center of Excellence at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. In P. Howie (Ed.), Art therapy with military populations: History, innovation, and applications (pp. 111–123). London: Routledge.

- Walker, M. S., Kaimal, G., Gonzaga, A., Myers-Coffman, K., & DeGraba, T. (2017). Active duty military service members’ visual representations of PTSD and TBI in masks. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2016.1267317

- Walker, M. S., Kaimal, G., Koffman, R., & Degraba, T. J. (2016). Art therapy for PTSD and TBI: A senior active duty military service member’s therapeutic journey. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 49, 10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2016.05.015

- Wall, P. L. (2012). Posttraumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury in current military populations a critical analysis. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 18(5), 278–298. doi: 10.1177/1078390312460578