ABSTRACT

This study examined the explanation for the found causal relationship between art therapy and positive therapeutic effects, in a previously conducted randomised controlled trial (RCT) with personality disorders cluster B/C. In-depth interviews were used to collect the data, in order to examine the experience without preconceived notions or expectations. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data to generate and interpret themes. Eight patients who participated in the RCT intervention were asked to evaluate their experiences with art media highlighting emotion regulation and Expressive Therapies Continuum (ETC) levels. Also three art therapists were asked to evaluate the artwork made by these participants. Thematic analysis resulted in five themes. These results suggested that through the targeted use of art assignments, material handling, and preferred approaches to art process and ETC levels, patients experienced, shaped and shared emotions not previously wilfully encountered. The therapeutic effects were explained by combined specific art therapy factors linked to the art media. These factors were reported by participants as evoking and helping them understand and regulate internal images and emotions. Results suggested that art therapy encourages a present-focused awareness and stimulates emotional processes evoked by material interaction.

Art therapy (AT) can be described as the therapeutic use of art making by people who experience illness, trauma or challenges in living, or by people who seek personal development within the context of a professional relationship. The purpose of AT is to improve or maintain mental health and emotional well-being through the use of drawing, painting, sculpture, photography and other forms of visual art expression (Malchiodi, Citation2012). AT has been accessed and used effectively by people with a diagnosis of personality disorder (PD) who are struggling with serious emotional and self-regulation problems (Springham, Findlay, Woods, & Harris, Citation2012). Disorganised or anxious attachment due to childhood maltreatment has been hypothesised as a mediator between childhood maltreatment and adult PDs (e.g. Beeney et al., Citation2017; Levy, Johnson, Scala, Temes, & Clouthier, Citation2015). PDs are defined as long-standing and typically inflexible maladaptive patterns of thought, behaviour and emotion that cause distress and interfere with individuals’ ability to relate to others and function in the world. PDs in the B/C clusters are characterised by significant difficulties with emotion regulation, problematic thought patterns, and unstable behaviour (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Therapists believe AT is a powerful intervention in the treatment of PDs, and patients reported that AT had beneficial therapeutic effects in a former qualitative study by Haeyen, van Hooren, and Hutschemaekers (Citation2015). The results of a recent randomised controlled trial (RCT) by Haeyen, van Hooren, van der Veld, and Hutschemaekers (Citation2017) showed that art therapy was an effective treatment with mainly large to very large effect sizes (e.g. impulsivity Δd = −1.66, detached emotional state Δd = −1.31, ‘happy child’ state Δd = 1.55, ‘healthy adult’ state Δd = 1.60; symptom distress Δd = −1.94) but these results do not elucidate the possible working factors.

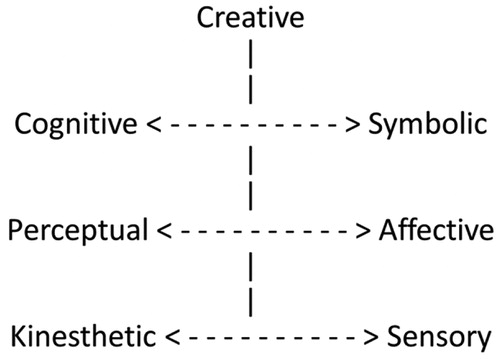

What art therapy-specific aspects were responsible for these effects in patients with PD? Sound evidence to answer this question is lacking. While art therapy has many supposed therapeutic factors, what sets it apart from verbal therapy is the application of art materials. Hinz (Citation2009), Hyland Moon (Citation2010) and Malchiodi (Citation2012) have discussed the use of art materials in art therapy assessment with materials placed on a continuum from high to low structure based on their inherent properties. Art materials with properties that provide high structure are easier to control, whereas those with low structure are more fluid and more difficult to control; therefore, materials with different structural qualities evoke different art-making experiences (Malchiodi, Citation2002; Schnetz, Citation2005; Virshup, Riley, & Sheperd, Citation1993). Art materials with high structure evoke more cognitive experiences, whereas fluid art materials evoke more affective experiences (Hinz, Citation2009). Based on the work of Kagin and Lusebrink (Citation1978), Hinz (Citation2009) elaborated the role of art media on the therapeutic experience through the model of the Expressive Therapies Continuum (ETC). The ETC describes how people characteristically take in, organise, process (make sense of) and express information to form images during interactions with art media. The processes are organised in bipolar levels: Kinesthetic/Sensory (K/S), Perceptual/Affective (P/A), Cognitive/Symbolic (C/Sy) and Creative (Cr) (see ).

Figure 1. The Expressive Therapies Continuum (Hinz, Citation2009).

Every component of the ETC is hypothesised as having a healing function that is reparative, and an emergent function representing a potential direction for therapeutic change.

The left ‘pole’ represents cognitive styles and the right ‘pole’ emotional styles of information processing. The underlying assumption is that the processes that people use during artistic creation mimic the patterns of thought, feeling and action displayed in other aspects of their lives but this hypothesis needs empirical support (Hinz, Citation2009). The ETC theory links patients’ preferences for art materials and processes to overused, underused or blocked styles of information processing and provides a framework for the selection of materials and methods in art therapy. According to the theory, patients may benefit from art experiences that balance overused component functions, help them use and value underused functions, or open up blocked components. They also may benefit from increased mentalization and the effects of group participation. The ETC theory proposes that the way patients process information in art therapy influences psychological, emotional, behavioural and cognitive functioning which, in turn, influences coping skills and attitudes towards new situations and challenges. Observing patients’ material interaction – the way they interact with art materials – may enable art therapists to gain insight into their amount of rationalisation, flexibility and motivation. Furthermore, based on an analysis of the formal elements of patients’ art products, Pénzes, van Hooren, Dokter, Smeijsters, and Hutschemaekers (Citation2016) concluded that impartial art therapist judges were able to accurately describe patients’ material interaction and related psychological characteristics. The accuracy of their descriptions was determined by comparing judges’ and treating art therapists’ case descriptions. However, an important aspect of explaining art therapy effects is looking at patients’ material interaction and their own understanding of this interaction for the therapeutic process rather than depending on the descriptions of external ‘expert’ judges.

Patients with PDs cluster B/C have mentioned that art therapy is valuable because of its perceived effects, including improved sensory perception and emotion regulation, better insight/comprehension, positive behaviour change, and greater personal integration (Haeyen et al., Citation2015). Art therapy seems a suitable intervention because PD is characterised by dysregulation of emotions and instability of the self and art therapy helps improve insight and increases positive development and stabilisation. Patients stated that the added value of art therapy in relation to verbal therapy is that they experience art therapy mainly as a more direct way to access more unconscious emotions because art materials and art making appeal to bodily sensations and emotional responses (Haeyen et al., Citation2015). Compared with more cognitive verbal therapies, art therapy is perceived as a good, and sometimes even better, method for PD patients to explore dysfunctional patterns of managing emotions, especially for people whose verbal skills are limited (Bernstein, Arntz, & de Vos, Citation2007; Haeyen et al., Citation2015). The study by Haeyen et al. (Citation2015) showed that for many patients, art therapy was a more direct way to access less-conscious or non-articulated emotions through a working method that was essentially based on experience. Art therapy confronts people in a direct way with their own patterns of feelings, thoughts and actions. This fits the core problems of people with PD such as managing emotions and having lower emotional awareness (Levine, Marziali, & Hood, Citation1997; Linehan & Heard, Citation1992; Westen, Citation1991). Art therapy is developed as a ‘bottom-up’ strategy for emotion regulation, starting with experiences using mental images, and then aimed at behaviour change and resulting insight (Haeyen, van Hooren, et al., Citation2017; Horn et al., Citation2015). In contrast, verbal therapy is considered a ‘top-down’ strategy, starting with cognitions to manage emotional experiences.

The results of a recent randomised controlled trial (RCT) by Haeyen, van Hooren, et al. (Citation2017) showed that art therapy is an effective treatment for PD patients because it not only reduces PD pathology (e.g. emotion dysregulation) and maladaptive behaviour, but it also helps patients to develop adaptive behaviours that indicate better mental health and self-regulation. The causal relation between art therapy and the therapeutic effects in this RCT was determined using quantitative outcome measures. These outcome measures, however, were not art therapy-specific but focused on general psychological functioning and PD symptoms. The question remains as to what role the art medium itself played in achieving these results. Therefore, in this study, we focused on art therapy-specific factors by evaluating experiences with the art media from patient and art therapist perspectives. The aim of this study was to determine the causal explanation (Lub, Citation2014) for why art therapy led to the effects achieved in the RCT intervention. Although it may seem artificial to separate the effects of material interaction from other aspects of group art therapy, the intent of this investigation was to highlight the role of art making as the participants experienced it. The reason for this exclusive focus was to expand the accumulating evidence on the therapeutic aspects of material interaction from the patient perspective.

Methods

The present study draws on data from the randomised controlled trial mentioned above. This trial was registered and approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands (METC) (CCMO register: NL44394.091.13 and Dutch Trial Register: NTR3925, same as the ISRCT or NCT number).

In this qualitative study thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) was used to identify, analyse, and report patterns (themes) within data. Various aspects of the research topic were interpreted following Boyatzis (Citation1998). Participants were interviewed according to the naturalistic inquiry (NI) method (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985) because this method is characterised by a low degree of manipulation of variables prior to and during investigation. Therefore, the focus could remain on what patients experienced when absorbed in genuine AT experiences in a natural setting. This thematic analysis used a theoretical or deductive analysis process of coding the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) because of our quite specific research questions about whether and how the art media played a role in therapeutic effects of art therapy, focusing on art therapy-specific factors by evaluating experiences with the art media.

Participants and procedure

In the RCT, participants were recruited from a waiting list that included patients indicated for PD-treatment in a specialised outpatient treatment unit for personality disorders. Inclusion criteria were: adult (18+) with a primary diagnosis of at least one personality disorder cluster B and/or C or a personality disorder not otherwise specified (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013) as determined with structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II, IQ >80, and adequate mastery of the Dutch language. Exclusion criteria were: acute crisis, psychosis, actual and serious suicidal behaviour and/or thoughts, and severe brain pathology. After signing informed consent forms, a total of 74 participants were randomly assigned to the RCT, which consisted of (1) weekly group art therapy (1.5 hours, 10 weeks) or (2) waiting list control.

A diverse group of eight participants from the experimental group of the RCT was selected based on gender, age, and they signed an additional consent form for this study. This process is a form of theoretical sampling (Charmaz, Citation2006). In the first cycle, four ex-RCT-participants were selected at least five months after finishing their last art therapy session. This five-month period was set because the participants might evaluate AT with some distance. In the second cycle, another four ex-RCT-participants were selected based on the first two and two additional criteria: they were present for at least 8 out of the 10 sessions and their artwork was available to help them recall the art therapy process. Based on the analysis of the data from the first cycle, they were added to gain an even stronger focus on the specific aspects of AT. In the second research cycle, participants were selected in search of new information around the selected categories and to obtain more specific information on the specific aspects of art therapy.

The patient participant group consisted of two men and six women within an age range from 22 to 50 years and a mean age of 36.75 years. The diagnoses of the complete patient sample were: Borderline 30%, Avoidant 20%, Obsessive-compulsive 20%, Narcissistic personality disorder 10% and Personality disorders not otherwise specified 20%. The gender distribution of the patient sample was about the same as the RCT experimental group (71.1% women). Sixteen patients were asked and eight of them did not want to be interviewed mentioning reasons like: not wanting to think about a difficult period when they needed mental care, work commitments, no baby sitter, no interest or unknown. Three art therapists with an average of 15 years of art therapy experience and representing two countries were interviewed based on a series of images created by participants. Two art therapists also were interviewed five months after the therapy sessions. The third art therapist was not involved in the RCT sessions and could therefore take a more distant perspective.

All participants read and gave feedback on written summaries of their interviews and the first interpretive statements to see if these represented their view. Participants did not suggest any changes. Through this process, new data were compared with previous data and previous data were repeatedly compared with new data.

Instruments

Loosely structured in-depth (NI) interviews were conducted, proceeding inductively and using an unstructured format. A list of sensitising topics based on the analytic interest coming from the research questions was used to prevent important subjects from being neglected and to bring fluency to the conversation. The general instruction which formed the starting point for the interview was: ‘How do you view the artwork that you have made during the research group?’ Topics included: former experience with art making, art assignments and methods as well as the experience of what worked, what did not and why? The present artwork was used to concentrate the conversation on personal characteristics, processes and how emotions were affected.

Patient interviews took place in the art therapy room with the idea of triggering the feelings originally accompanying the sessions. Patient artwork was present, which helped the conversation remain concrete and specific. Each respondent was interviewed once for about 50 minutes.

Intervention: art therapy

The 10-week art therapy programme for patients with personality disorders consisted of a structured art therapy protocol available from the first author. The principles of Intervention Mapping were applied to guide the development, implementation, and planned evaluation of the art therapy intervention (Haeyen, van Hooren, Dehue, & Hutschemaekers, Citation2017).

The protocol consisted of specific art therapy assignments for personality disorders extracted from the workbook Don’t Act Out but Live Through (Haeyen, Citation2007). The art assignments involved individual, dyad and group assignments. The art assignments were aimed at improving mindfulness, self-validation, emotion regulation skills, interpersonal functioning, insight and comprehension.

Each session started with a check-in period and explanation of the experiential assignment and session goals and ended with a therapist-led group discussion and reflection on the art process and product. An example of the content of one session is presented in . The protocol was designed for an open group with a maximum of nine participants, meaning that participants could start at different times but always participated in a cycle of 10 sessions and therefore, the number of participants in each session varied. A senior art therapist and an art therapy student carried out the RCT protocol.

Table 1. Example of AT session content and objectives.

Analysis

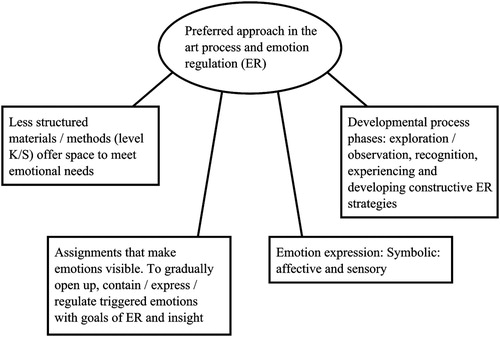

We familiarised ourselves with the data through preparing transcripts of the interviews by fully transcribing audio recordings. Consistent with the further phases of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), we generated initial codes and organised the data in meaningful groups. We approached the data with the specific research questions in mind. We searched for the main themes sorting the different codes into potential themes, and collating all the relevant coded data extracts within the identified themes. and show the process of coming to the themes. We re-read the entire data set to review and refine themes. Finally, themes were defined and refined identifying the essence of what each theme was about (as well as the themes overall) and we produced the analytic narratives related to our research questions. The definite themes were: experiences with the art assignments, material handling/interaction, preferred approach in the art process and the ETC level, preferred approach in the art process and emotion regulation, and therapeutic value of the combination of these factors.

Table 2. Data extract, with codes applied.

Criteria of quality

Several techniques were used to ensure that data met the criteria of ‘trustworthiness’ and ‘credibility’ (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2005). Theoretical sampling was applied in accordance with which goal-oriented selection of participants aimed at obtaining ‘rich information’ up to a point of information saturation. We searched for maximum variation of cases, based on gender, age, and PD to ensure that diverse perspectives were incorporated. We also interviewed patients as well as art therapists.

To minimise the interviewer effect we performed member checking by involving participants in verifying the transcriptions. They received the initial texts: written summaries of their interviews and interpretive statements to see if these represented their view and were given the opportunity to respond to and/or correct them. Participants did not suggest any changes. Based on this check the criterion of credibility was met. To ensure that the findings were grounded in data and not biased by the investigators’ motivation or interest, the whole process of analysis was peer debriefed by involving three art therapists from the field and two research experts related to a university art therapy programme and independent from the study to critically check and discuss the data analysis in the different phases. This meets the criterion of confirmability. The in-depth exploration of experiences with art media focused on emotion regulation and the comparative analysis with the interviews of the previous phase enhanced the transferability. The experiences of patients were first-hand to ensure the criterion of authenticity.

Results

Answers to the question of what role the art media played in emotion regulation in PD patients are presented in five different themes: experiences with the art assignments, material handling/interaction, preferred approach in the art process and the ETC level, preferred approach in the art process and emotion regulation, and therapeutic value of the combination of factors. In each theme the information from patients and art therapists is integrated into a summarised result. The art therapists’ descriptions of the art processes were reasonably aligned, although with different emphases. The patients formulated their experiences in differentiated, personal ways.

Experiences with the art assignments

Patients indicated that the art assignments offered them safety, permitting them to confront hidden and ‘shielded’ emotions and allowing visibility to what previously was ‘below the surface’. The art assignments held a mirror for them. Patients stated that they gained insight into the ways they shied away from intense emotion and that they experienced the expression of emotions through artwork as more pleasant than their expression in words. Therefore, expression in art supported the understanding and acceptance of emotions as well as the sharing of emotions with others. In addition, art assignments provided opportunities to experiment with and better regulate emotions.

Interestingly, although the overall experience was described as safe, many art assignments were initially experienced as ‘confrontational and painful’. It took some time and distance for patients to recognise their healing effects. This initial confrontation was important in helping patients develop an understanding of their problems and the origins of dysfunctional behaviour. For example, the art assignment, ‘The lifeline’ caused patients to re-experience difficult moments in their lives and the development of personality problems could be seen in art elements such as intensity of colour, connectors, and symbol use. This art assignment was experienced as confrontational both during creation and in subsequent group discussion. In the interviews, participants stated that although creating their lifelines brought about significant pain, they gained from them significant insight. Over time, strong negative emotions declined; memories were given a proper place in the past, and greater balance was experienced in the present.

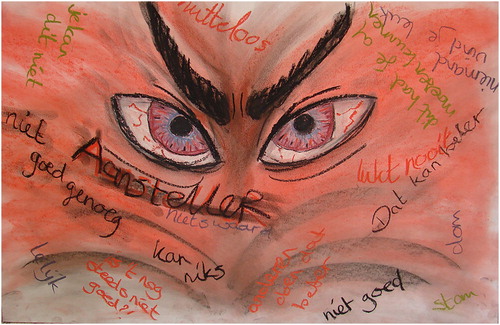

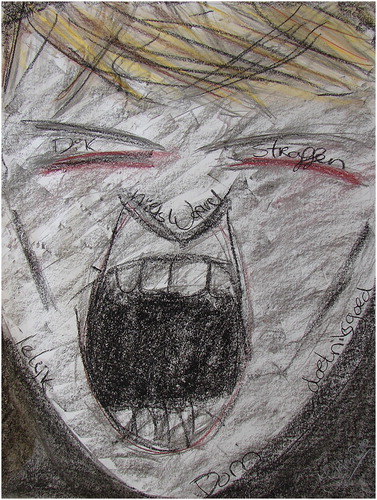

The portrayal of the ‘Inner Tormentor’ also was confrontational. One patient said that the image broke through armour and touched her greatly; she literally came face-to-face with her tormentor (see ).

The art assignments gave patients the impetus to become more open to experiencing strong emotions. They could no longer avoid themselves but were faced with their rigid behavioural patterns, and emotions came to the surface that previously had been avoided/ignored.

By the art assignments I came really in touch with myself. I am really someone who just slides everything under the carpet and pretends nothing is going on. And then it came all of a sudden to me, you know, I had no idea how I had to deal with that actually. (male, 24 yrs)

Material handling/interaction

All patient participants handled art materials in personalised ways and showed individual preferences in the ways they approached the art assignments.

When I feel very angry, then I need to be able to work with nails and with things that well, almost are stinging and if I want to create a sense of security, then I will go very much with pink colours and with ‘fluffy’ stuff and feathers and those kind of things. So that’s very different. (female, 43 yrs)

Here, I discovered soft pastels. That you can sweep it! I am still a fan of this material. You have the possibility to blend one colour into the other and to use it very soft, but also use it with more pressure in combination with oil chalk. […] If you’re talking about depicting feelings it is sometimes so gradually. I still find it a pleasant medium. (female, 47 yrs)

Many patients related interaction with preferred materials to the disentangling of emotions and feeling ‘stuck’. This disentangling process was visible in the artwork in which the use of familiar and unfamiliar materials and techniques brought patients back to primary feelings, directly confronting emotional blockages. In interviews the majority of the patients described that using new materials/techniques offered them new experiences and often different views on dealing with their personality problems and emotional (dys)regulation. Patients also claimed that this confrontation occasionally led to shielding themselves from troublesome thoughts and emotions.

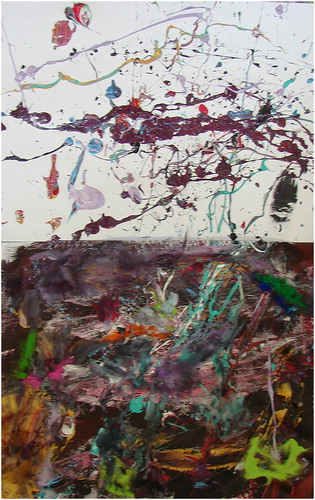

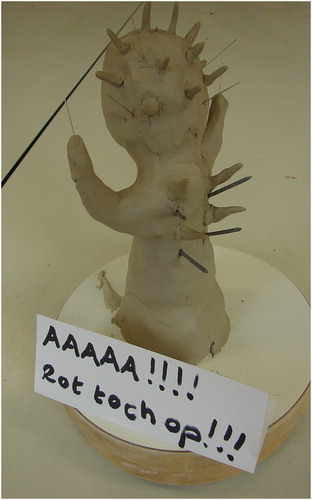

Throwing with paint … that was the most fun! [ … ] I just felt like a child again, you know, just youthful. All together with the others making a mess, having fun. My critical thoughts were hindering me a little bit like: ‘don’t do this, you are going way too loose!’ (see , female, 21 yrs)

What I was making and the way I did this gave insight of what’s on the unconscious level, unconscious in the depth of my inner self […]. Sometimes I was terrified of the confrontation. You get literally an image that translates what lives inside you, and that is also tangible … (female, 54 yrs)

Here, I discovered soft pastels. That you can sweep it! I am still a fan of this material. You have the possibility to blend one colour into the other and to use it very soft, but also use it with more pressure in combination with oil chalk. […] If you’re talking about depicting feelings it is sometimes so gradually. I still find it a pleasant medium. (female, 47 yrs)

Preferred approach in the art process and the ETC level

The majority of patients were able to clarify the rationale for their preferred material handling and it was striking that this preferred approach was unique to each participant. In addition, therapists pointed out how different therapeutic needs of the patients related to their preferred approaches to the art media and ETC components.

In articulating their preferences for the ways that they approached the art assignments, some patients mentioned that they preferred to start from the Cognitive/Symbolic level, others from the Perceptual/Affective level and still others from the Kinesthetic/Sensory level. Each participant linked his personal approach to art making to feelings or experiences that were blocked, a therapeutic need, or a desire for emotional/psychological safety. The following participant recognises that his cognitive approach is not working when art making:

I am quite cognitive. But that is for me a way to escape and when I am making art then … Yes, just as the body is not lying, an image is not lying either. So that gives me a lot of information about what is currently playing where you are not always aware of. (male, 40 yrs)

Patients also noticed the point when they started to use a different ETC component approach and whether or not they were conscious of it at the time. The following quote illustrates one patient’s ability to describe the preferred approach and its therapeutic meaning.

Yes, I really work from my feelings. That just flows. Yes, when I get an art assignment I actually do not think. Except, when I intentionally need to depict something. Then I find it very difficult. Then the critical me emerges who’s just reclaiming: ‘you can’t draw and you can’t show it, it looks like nothing’. I should just really work abstract and have a range of materials that I just can grab on feeling. (see , female, 32 yrs)

Preferred approach in the art process and emotion regulation

The relationship between the art processes and emotion regulation was clearly noticed by both patients and art therapists. Therapists observed that, at the beginning of a series patients needed to structure their images so that the emotion was not apparent. As one therapist reacted to the artwork:

… the images seem to want to tell a story in which the confirmation comes from the cognitive and symbolic control over the emotional response. (therapist, 50 yrs)

They then noticed that patients gradually opened up to their emotions making them visible in the art process. They mentioned that by using materials and methods that were more or less structured or controlled patients found space to regulate emotion. The material interaction offered a range of possible emotion regulation strategies.

I observe in the art works that this participant releases control in the course of the time and is more intensely absorbed in the material (sensory fingerprints in the clay and experimenting with paint). (therapist, 37 yrs)

Patients indicated that through the art assignments and resulting images, they obtained more insight than from verbal therapy into the functioning of their emotions and behaviours originating from them. Their comments showed that the art assignments were valued for their ability to regulate emotion. Many patients also realised that they had gone through a developmental process during the 10 sessions of art therapy that allowed them to observe their own emotions, understand emotion regulation, and develop more functional behaviour. The following quote speaks for itself:

… a word from then was ‘confrontational’ and when I look back at it now, the word of now would be ‘healing’ by turning something negative into something positive, for example by putting it in this way on paper. (female, 43 yrs)

Most patients indicated that certain art assignments were particularly emotionally evocative (e.g. ‘Image of pain and soothing’, ‘The lifeline’). Emotions were triggered at the outset by the choice of materials and at the end by aspects of the completed image. Despite the difficult emotions that arose and were experienced during challenging art assignments, patients felt satisfaction and empowerment in being able to add soothing or hard materials to images to strengthen or soften the expression and to meet their emotional needs. This knowledgeable choice of materials and processes allowed patients to contain or express intensely painful emotions and in doing so, regulate them. In the following quote a patient described her attempts to use words to protect herself from feelings and emotions.

… which I find very much with that anger, that one, that is for me still really the most confrontational of them all. [ … ] because I just felt good but that came out. Then I thought, oh, this is in me too and I do not have any contact with it. (see , female, 33 yrs)

The art therapists commented on striking changes that they observed in the middle of the intervention period in all art processes. They noted that when patients experienced a sense of psychological safety, more space was given to emotions and that patients seemed to experiment with alternative behaviour to develop new patterns in emotions, thoughts or actions.

I came across my own pattern … I notice, for example, that as soon as I started working with others I was focused on what the other person wanted and that is very, very tiring. (Through the art therapy process) I felt at ease to practise with focusing more on myself. (female, 21 yrs)

The therapeutic value of the combination of factors

All patients mentioned that art assignments and images helped them gain insight into their problems, because emotions and feelings came more ‘to the surface’. The art interventions stimulated improved emotion regulation due to the material interactions, the appeal of art media, and patients’ preferred and challenging approaches or ETC levels. In addition, the strengthening or weakening of formal artistic elements such as colour, line, form, movement and/or composition played a part in allowing patients to open up to the experiences. For example, making colours brighter or more intense or making forms more powerful amplified emotional expression. Making colours softer by using pastel colours or mixing with white or creating softer, more organic forms aided the soothing of emotions.

All participants, both patients and art therapists, mentioned in their interviews that painful emotions and anxious feelings are not easily expressed and that often, verbal therapy was not sufficient to aid their understanding or expression. The following quote supports how the use of sharp materials helped a patient gain greater emotional awareness:

This artwork is made with reverse beer caps, which are very sharp as you feel them. That hurts very much and that, yes, that’s exactly what I felt. And when I see this now, I think: Yes those painful things there are, and are still there, but it does not affect me that much anymore. I can now express these (feelings), also in words. (male, 40 yrs)

The therapists can reach the key, but the door can only be opened from the inside, you must take the first steps yourself. They can offer help but if you keep the door shut, it is not going to happen. (female, 33 yrs)

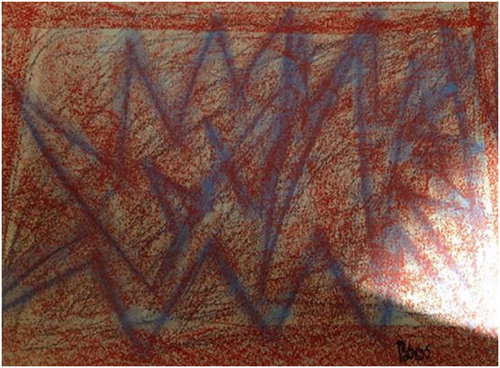

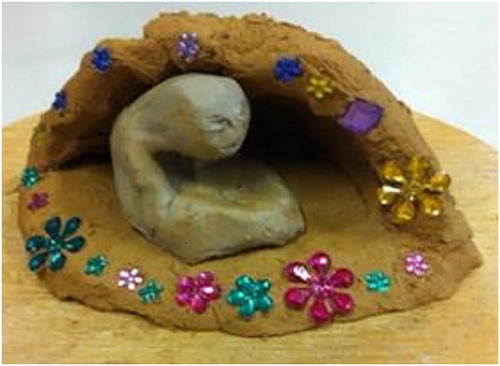

I've had times that I almost could not feel and at that point art therapy worked very well for me. By getting in touch with my senses, more than in verbal therapy. But actually I unconsciously repressed a lot about this. In the art I could process it and place it. I also made art works that I only understood later. (see , female, 47 yrs)

I see it in that assignment, that it then all of a sudden shows what is going on below the surface and above. […] I show in this picture what I never have or never dare or want to have talk about with someone and I just bring it in the image (!). I have been very busy with that assignment: ‘Big self & little self’. That your grown up self understands your little self, why you did what you did back then. I worked the clay softly, it felt nurturing. I blamed myself for many things, also for what I did as a 7-year-old. But at that age you don’t make those decisions. […] I guess that is why I kept going on. (female, 54 yrs)

The art therapists underscored the distinctive and specific therapeutic value of the art interventions regarding emotion regulation. Both patients and art therapists confirmed that by using art materials and processes, emotions were experienced and contained and that art therapy was ideally suited to uncovering and regulating unconscious internal images and emotions.

Discussion

In this study the effects found in a previously executed RCT on art therapy for patients with personality disorders (Haeyen, van Hooren, et al., Citation2017) were causally explained by combined specific art therapy factors. Through the targeted use of art assignments, material handling, and their preferred approaches to the art process, patients experienced, shaped and shared emotions not previously wilfully encountered. Art therapy seems ideally suited to evoke and regulate internal images and emotions. Results of the current study emphasise that the art medium had a central role in promoting the beneficial effects.

The art assignments gave people diagnosed with personality disorders the impetus to become more open to experiencing and expressing strong emotions. They could no longer avoid themselves or their feelings but were faced with their enduring maladaptive and inflexible patterns of cognitions, emotions and behaviours which are a core issue for this target group. Through the use of art, emotions surfaced that previously had been consciously or unconsciously avoided or ignored. Material interactions varied among participants and results highlighted that with this personalised interaction came the ability to regulate emotion. By becoming aware of material interaction, participants gained new insight into dealing with their problems. Preferred approaches to the art process and ETC levels used also were different for each patient and related to unique personal needs. With experience, patients were able to understand and initiate their preferred material handling to meet their own therapeutic needs. Material interaction offered a range of possibilities for emotion regulation strategies and emphasised that verbal therapy is not always sufficient. The art process came forward as partly intentional and explicit because cognitive control and reflection took place during and after the art making. However, the process also was implicit and less conscious. Unintended personal themes could pop up or be triggered in the process of art making, and material interactions sometimes brought up previously unconscious emotional responses.

The therapeutic value of art therapy for patients with personality disorders seems to result from the combination of the specific art therapy factors described in this article and the processes involved are highly relevant for this target group. The process of self-expression is an important facet of art therapy and concerns the expression of personality characteristics, thoughts and feelings in painting, poetry or other creative activities. Art therapy addresses the core emotional needs such as freedom to express valid needs and emotions, spontaneity, play and autonomy (Young, Klosko, & Weishaar, Citation2003). In addition, self-expression could also be linked to authenticity (e.g. values, goals, traits) (Kokkoris & Kühnen, Citation2014; Kraus, Chen, & Keltner, Citation2011). The process of emotion regulation implies the recognition and acceptance of emotions, as well as problem solving and reappraisal, which appear to be protective against psychopathology and the opposite of dysregulation, which involves suppression, avoidance and rumination (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, Citation2010; Gross, Citation1998a, Citation1998b; Koole & Rothermund, Citation2011).

The value of art therapy in emotion regulation could be the experiential nature of art therapy that encourages a here-and-now awareness and the positive and negative emotional processes evoked by material interaction. Acceptance of one’s own and others’ self-expression aids adaptive emotion regulation, increases positive experiences and enhances mental health. Art therapy provides a non-threatening, accepting and concrete context for (negative) emotions to occur. This helps patients appraise emotions as momentary phenomena, controllable and less aversive and subsequently reduces the activation of underlying habitual, negative beliefs such as feeling incompetent, not in control and/or worthless. This emotional and psychological process may make patients more resilient or flexible. Flexibility or resilience, which can be described as the ability to adapt and self-manage in the face of social, physical, and emotional challenges (Huber et al., Citation2011), is essential for mental health. A well-functioning person has access to both ‘rational’ and ‘affective’ aspects in adapting to daily life challenges (Antonovsky, Citation1984; Hinz, Citation2009; Vossler, Citation2012). Flexibility in adapting to daily life challenges can be seen as analogous to patient–material interaction in art therapy. Assessing patients’ style of material interaction in adapting to the intrinsic properties of the art materials being used can indicate whether patients are flexible in using both rational and affective processes (Pénzes et al., Citation2016).

Limitations of the current study need to be considered. First, the number of participants was small, making it hard to generalise the results to the total target group or to PD in general. In order to obtain a more valid and reliable outcome it would have been better to interview a larger number of participants. Only a relatively small subset of participants had complete photosets of all the art images. However, the characteristics of the participating patients were similar to the complete RCT sample. Second, some participants had previous experience with art therapy and were therefore more familiar with the art therapy assignments and with exploring, discovering, and experiencing their emotions through art. The positive results achieved might have been due to increased familiarity and not merely to the intervention protocol used in the RCT. Third, the group of participating patients might be selective in terms of motivation and reflectiveness compared to others who did not participate. Finally, an intervention of 10 weeks is short. The results of this study should be seen in the context of this limited time period. However, the results are clear and a point of strength of this research was that they were obvious to participants and art therapists alike.

The findings of this study indicate that having knowledge of and experience with the possibilities and restrictions of a wide range of art assignments and art materials and with the ability to work with various ETC levels are important conditions for art therapists to give meaning to patients’ self-expression and material interaction. Therefore, art therapists are strongly advised to maintain and elaborate their skills and knowledge of art assignments, art materials and interactional processes, all linked to psychological characteristics and emotional issues of their target groups. Further research is needed to investigate the specific application of art therapeutic assignments, art materials, and the therapeutic working with the ETC levels in art therapy focused on emotion regulation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Suzanne Haeyen, Art Therapist (MA, PhD student), works in an intensive multidisciplinary outpatient treatment of ‘Scelta’, an expert centre for personality disorders, and is chairperson for the arts therapists, both at GGNet (Mental Health Institute in the Netherlands). She is also a senior lecturer of the part- time study for Art Therapy of the University of Applied Science of Arnhem & Nijmegen (HAN CTO). She has several publications about art therapy with personality disorders and participated in the development of the national multidisciplinary guidelines for the treatment of personality disorders.

Marlous Kleijberg, Art Therapist, works in a multidisciplinary elderly treatment programme at GGNet (Mental Health Institute in the Netherlands). She is also a 1st degree art teacher and currently working as independent art coach on behalf of arts and culture projects for culture education and the social domain.

Lisa D. Hinz, Ph.D., ATR, is a licensed clinical psychologist and a registered, board certified art therapist. She studied art therapy at the University of Louisville where she worked with Drs. Kagin and Lusebrink, the originators of the Expressive Therapies Continuum. Dr. Hinz is an adjunct professor of art therapy at Notre Dame de Namur University and she is the author of many professional publications including the Expressive Therapies Continuum: A Framework for Using Art in Therapy.

ORCID

Suzanne Haeyen http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0351-7729

References

- Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Handboek voor de classificatie van psychische stoornissen (DSM-5) [diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders]. Dutch translation. Amsterdam: Boom.

- Antonovsky, A. (1984). The sense of coherence as a determinant of health. In J. Matarazzo (Ed.), Behavioural health: A handbook of health enhancement and disease prevention (pp. 114–129). New York, NY: John Wiley.

- Beeney, J. E., Wright, A. C., Stepp, S. D., Hallquist, M. N., Lazarus, S. A., Beeney, J. S., … Pilkonis, P. A. (2017). Disorganized attachment and personality functioning in adults: A latent class analysis. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 8(3), 206–216. doi: 10.1037/per0000184

- Bernstein, D. P., Arntz, A., & de Vos, M. (2007). Schema focused therapy in forensic settings: Theoretical model and recommendations for best clinical practice. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 6(2), 169–183. doi: 10.1080/14999013.2007.10471261

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. London: Sage.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory. A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage.

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Handbook of qualitative research. London: Sage.

- Gross, J. J. (1998a). Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 224–237. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.224

- Gross, J. J. (1998b). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271

- Haeyen, S. (2007). Niet uitleven maar beleven. Beeldende therapie bij persoonlijkheidsproblematiek [don’t act out but live through. Art therapy in personality issues]. Houten: Bohn Stafleu & van Loghum.

- Haeyen, S., van Hooren, S., Dehue, F., & Hutschemaekers, G. (2017). Development of an art-therapy intervention for patients with Personality Disorders: an Intervention Mapping study. The International Journal of Art Therapy. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2017.1403458

- Haeyen, S., van Hooren, S., & Hutschemaekers, G. (2015). Perceived effects of art therapy in the treatment of personality disorders, cluster B/C: A qualitative study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 45, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2015.04.005

- Haeyen S, van Hooren S, van der Veld W, & Hutschemaekers G. (2017). Efficacy of art therapy in individuals with personality disorders cluster B/C. A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Personality Disorders, 1–16. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2017_31_312

- Hinz, L. D. (2009). Expressive therapies continuum: A framework for using art in therapy. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Horn, E., Verheul, R., Thunnissen, M., Delimon, J., Soons, M., Meerman, A., … van Busschbach, J. (2015). Effectiveness of short-term inpatient psychotherapy based on transactional analysis with patients with personality disorders: A matched control study using propensity score. Journal of Personality Disorders, 29(5), 663–683. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2014_28_166

- Huber, M., Knottnerus, J. A., Green, L., van der Horst, H., Jadad, A., Kromhout, D. … Smid, H. (2011). How should we define health? British Medical Journal, 343, d4163. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4163

- Hyland Moon, C. (2010). A history of materials and media in art therapy. In C. H. Moon (Ed.), Materials and media in art therapy: Critical understandings of diverse artistic vocabularies (pp. 3–47). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Kagin, S. L., & Lusebrink, V. B. (1978). The expressive therapies continuum. Art Psychotherapy, 5, 171–180. doi: 10.1016/0090-9092(78)90031-5

- Kokkoris, M., & Kühnen, U. (2014). Express the real you: Cultural differences in the perception of self-expression as authenticity. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45, 1221–1228. doi: 10.1177/0022022114542467

- Koole, S. L., & Rothermund, K. (2011). “I feel better but I don't know why”: The psychology of implicit emotion regulation. Cognition and Emotion, 25(3), 389–399. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2010.550505

- Kraus, M. W., Chen, S., & Keltner, D. (2011). The power to be me: Power elevates self-concept, consistency and authenticity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(5), 974–980. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.03.017

- Levine, D., Marziali, E., & Hood, J. (1997). Emotion processing in borderline personality disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 185(4), 240–246. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199704000-00004

- Levy, K. N., Johnson, B. N., Scala, J. W., Temes, C. M., & Clouthier, T. L. (2015). An attachment theoretical framework for understanding personality disorders: Developmental, neuroscience, and psychotherapeutic considerations. Psihologijske Teme (Psychological Topics), 24(1), 91–112.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. A. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Linehan, M. M., & Heard, H. (1992). Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder. In J. Clarkin, E. Marziali, & H. Munroe-Blum (Eds.), Borderline personality disorder: Clinical and empirical perspectives (pp. 248–268). New York, NY: Guilford.

- Lub, V. (2014). Kwalitatief evalueren in het sociale domein. Mogelijkheden en beperkingen. Den Haag: Boom Lemma.

- Malchiodi, C. A. (2002). The soul’s palette: Drawing on art’s transformative powers for health and well-being. Boston: Shambhala.

- Malchiodi, C. A. (2012). Handbook of art therapy (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford.

- Pénzes, I., van Hooren, S., Dokter, D., Smeijsters, H., & Hutschemaekers, G. (2016). Material interaction and art product in art therapy assessment in adult mental health. Arts & Health, 8(3), 213–228. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2015.1088557

- Schnetz, M. (2005). The healing flow: Artistic expression in therapy. London: Jessica Kingsley.

- Springham, N., Findlay, D., Woods, A., & Harris, J. (2012). How can art therapy contribute to mentalization in borderline personality disorder? International Journal of Art Therapy, 17(3), 115–129. doi: 10.1080/17454832.2012.734835

- Virshup, E., Riley, S., & Sheperd, D. (1993). The art of healing trauma: Media, techniques, and insights. In E. Virshup (Ed.), California art therapy trends (pp. 429–431). Chicago,IL: Magnolia Street Publishers.

- Vossler, A. (2012). Salutogenesis and the sense of coherence: Promoting health and resilience in counselling and psychotherapy. Counselling Psychology Review, 27, 68–79.

- Westen, D. (1991). Cognitive-behavioral interventions in the psychoanalytic psychotherapy of borderline personality disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 11(3), 211–230. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(91)90101-Y

- Young, J., Klosko, J., & Weishaar, M. (2003). Schema therapy: A practitioner’s guide. New York, NY: Guilford.